Long QT syndrome

| Long QT syndrome | |

| |

|---|---|

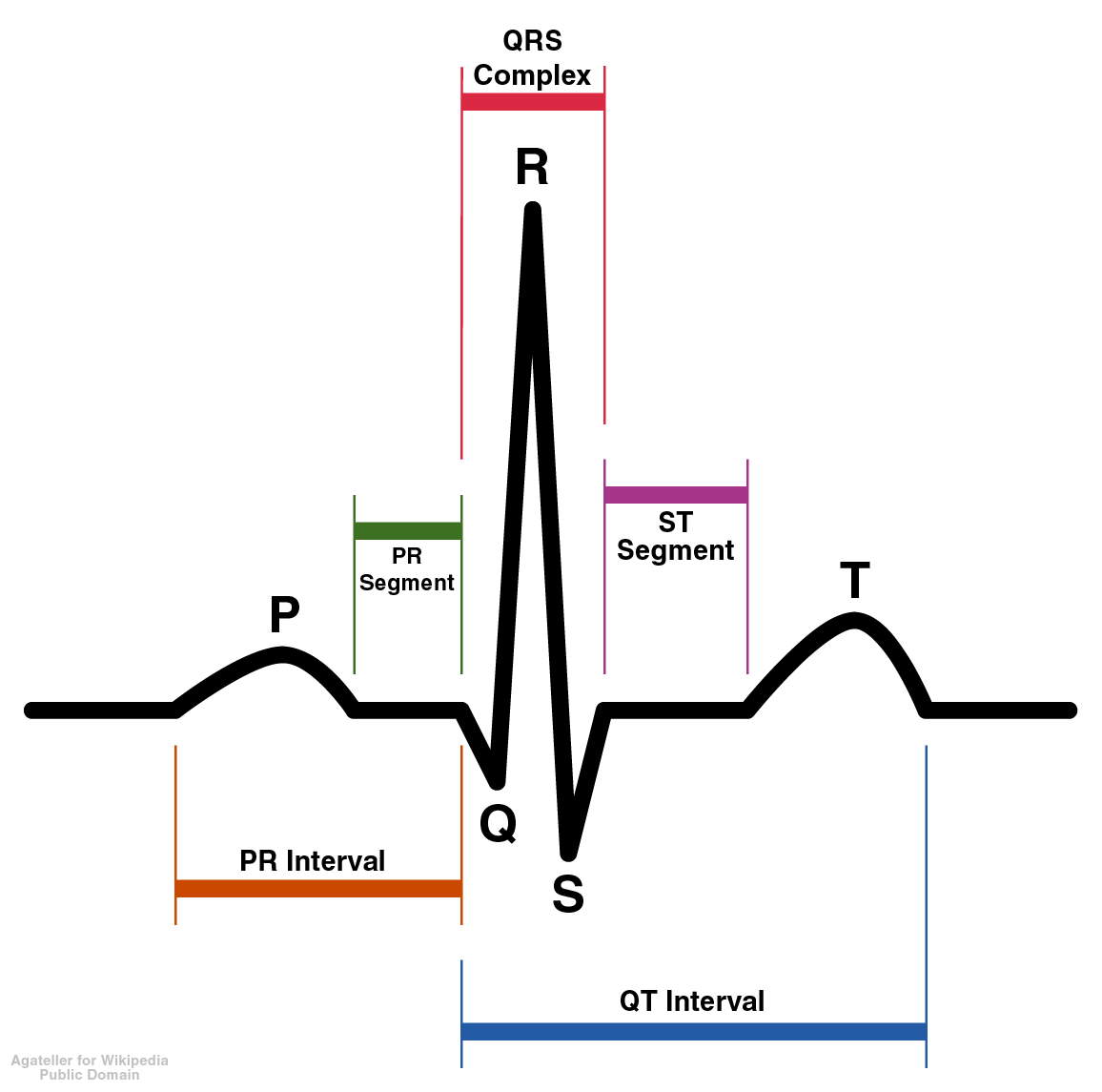

| Schematic representation of normal ECG trace (sinus rhythm), with waves, segments, and intervals labeled. | |

| ICD-10 | I45.8 |

| ICD-9 | 426.82 |

| DiseasesDB | 11104 |

| MeSH | D008133 |

|

Long QT Syndrome Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Long QT syndrome On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Long QT syndrome |

| Cardiology Network |

Discuss Long QT syndrome further in the WikiDoc Cardiology Network |

| Adult Congenital |

|---|

| Biomarkers |

| Cardiac Rehabilitation |

| Congestive Heart Failure |

| CT Angiography |

| Echocardiography |

| Electrophysiology |

| Cardiology General |

| Genetics |

| Health Economics |

| Hypertension |

| Interventional Cardiology |

| MRI |

| Nuclear Cardiology |

| Peripheral Arterial Disease |

| Prevention |

| Public Policy |

| Pulmonary Embolism |

| Stable Angina |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

| Vascular Medicine |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [2]; Associate Editor(s)-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [3]

Associated syndromes

A number of syndromes are associated with LQTS.

Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome

The Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (JLNS) is an autosomal recessive form of LQTS with associated congenital deafness. It is caused specifically by mutation of the KCNE1 and KCNQ1 genes

In untreated individuals with JLNS, about 50 percent die by the age of 15 years due to ventricular arrhythmias.

Romano-Ward syndrome

Romano-Ward syndrome is an autosomal dominant form of LQTS that is not associated with deafness.

Mechanism of arrhythmia generation

All forms of the long QT syndrome involve an abnormal repolarization of the heart. The abnormal repolarization causes differences in the "refractoriness" of the myocytes. After-depolarizations (which occur more commonly in LQTS) can be propagated to neighboring cells due to the differences in the refractory periods, leading to re-entrant ventricular arrhythmias.

It is believed that the so-called early after-depolarizations (EADs) that are seen in LQTS are due to re-opening of L-type calcium channels during the plateau phase of the cardiac action potential. Since adrenergic stimulation can increase the activity of these channels, this is an explanation for why the risk of sudden death in individuals with LQTS is increased during increased adrenergic states (ie exercise, excitement) -- especially since repolarization is impaired. Normally during adrenergic states, repolarizing currents will also be enhanced to shorten the action potential. In the absence of this shortening and the presence of increased L-type calcium current, EADs may arise.

The so-called delayed after-depolarizations (DADs) are thought to be due to an increased Ca2+ filling of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This overload may cause spontaneous Ca2+ release during repolarization, causing the released Ca2+ to exit the cell through the 3Na+/Ca2+-exchanger which results in a net depolarizing current.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of LQTS is not easy since 2.5% of the healthy population have prolonged QT interval, and 10% of LQTS patients have a normal QT interval. A commonly used criterion to diagnose LQTS is the LQTS "diagnostic score" [1]. Its based on several criteria giving points to each. With 4 or more points the probability is high for LQTS, and with 1 or less point the probability is low. Two or 3 points indicates intermediate probability.

- QTc (Defined as QT interval / square root of RR interval)

- >= 480 msec - 3 points

- 460-470 msec - 2 points

- 450 msec and male gender - 1 point

- Torsades de Pointes ventricular tachycardia - 2 points

- T wave alternans - 1 point

- Notched T wave in at least 3 leads - 1 point

- Low heart rate for age (children) - 0.5 points

- Syncope (one cannot receive points both for syncope and Torsades de pointes)

- With stress - 2 points

- Without stress - 1 point

- Congenital deafness - 0.5 points

- Family history (the same family member cannot be counted for LQTS and sudden death)

- Other family members with definite LQTS - 1 point

- Sudden death in immediate family (members before the age 30) - 0.5 points

Treatment options

There are two treatment options in individuals with LQTS: arrhythmia prevention, and arrhythmia termination.

Arrhythmia prevention

Arrhythmia suppression involves the use of medications or surgical procedures that attack the underlying cause of the arrhythmias associated with LQTS. Since the cause of arrhythmias in LQTS is after depolarizations, and these after depolarizations are increased in states of adrenergic stimulation, steps can be taken to blunt adrenergic stimulation in these individuals. These include:

- Administration of beta receptor blocking agents which decreases the risk of stress induced arrhythmias. Beta blockers are the first choice in treating Long QT syndrome.

In 2004 it has been shown that genotype and QT interval duration are independent predictors of recurrence of life-threatening events during beta-blockers therapy. Specifically the presence of QTc >500ms and LQT2 and LQT3 genotype are associated with the highest incidence of recurrence. In these patients primary prevention with ICD (Implantable Cardioverster Defibrilator) implantaion can be considered.[2]

- Potassium supplementation. If the potassium content in the blood rises, the action potential shortens and due to this reason it is believed that increasing potassium concentration could minimize the occurrence of arrhythmias. It should work best in LQT2 since the HERG channel is especially sensible to potassium concentration, but the use is experimental and not evidence based.

- Mexiletine. A sodium channel blocker. In LQT3 the problem is that the sodium channel does not close properly. Mexiletine closes these channels and is believed to be usable when other therapies fail. It should be especially effective in LQT3 but there is no evidence based documentation.

- Amputation of the cervical sympathetic chain (left stellectomy). This may be used as an add-on therapy to beta blockers but modern therapy mostly favors ICD implantation if beta blocker therapy fails.

Arrhythmia termination

Arrhythmia termination involves stopping a life-threatening arrhythmia once it has already occurred. The only effective form of arrhythmia termination in individuals with LQTS is placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). ICD are commonly used in patients with syncopes despite beta blocker therapy, and in patients who have experienced a cardiac arrest.

With better knowledge of the genetics underlying the long QT syndrome, more precise treatments will be readily available.[3]

Risk stratification

The risk for untreated LQTS patients having events (syncopes or cardiac arrest) can be predicted from their genotype (LQT1-8), gender and corrected QT interval.[4]

- High risk (>50%)

QTc>500 msec LQT1 & LQT2 & LQT3(males)

- Intermediate risk (30-50%)

QTc>500 msec LQT3(females)

QTc<500 msec LQT2(females)& LQT3

- Low risk (<30%)

QTc<500 msec LQT1 & LQT2 (males)

References

- ↑ Schwartz PJ, Moss AJ, Vincent GM, Crampton RS. Diagnostic criteria for the long QT syndrome. An update. Circulation. 1993 Aug;88(2):782-4. PMID 8339437.

- ↑ Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ, Grillo M, Bloise R, Ronchetti E, Moncalvo C, Tulipani C, Veia A, Bottelli G, Nastoli J. Association of long QT syndrome loci and cardiac events among patients treated with beta-blockers. JAMA. 2004 Sep 15;292(11):1341-4. PMID: 15367556

- ↑ Compton SJ, Lux RL, Ramsey MR, Strelich KR, Sanguinetti MC, Green LS, Keating MT, Mason JW. Genetically defined therapy of inherited long-QT syndrome. Correction of abnormal repolarization by potassium. Circulation. 1996 Sep 1;94(5):1018-22. PMID 8790040

- ↑ Risk Stratification in the Long-QT Syndrome: N Engl J Med 2003; 349:908-909, Aug 28, 2003. PMID 12944579.