Thrombus

|

WikiDoc Resources for Thrombus |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Thrombus |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Thrombus at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Thrombus at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Thrombus

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Thrombus Risk calculators and risk factors for Thrombus

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Thrombus |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Vanessa Cherniauskas, M.D. [2]

Synonyms and keywords: Thrombosis

Overview

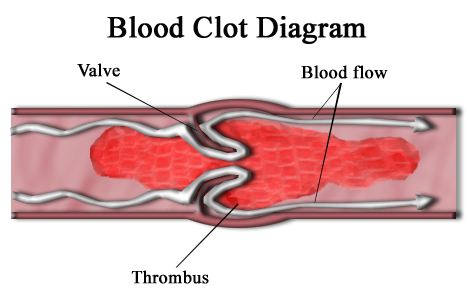

A thrombus, or blood clot, is the final product of the blood coagulation step in hemostasis. It is achieved via the aggregation of platelets that form a platelet plug, and the activation of the humoral coagulation system (i.e. clotting factors). A thrombus is physiologic in cases of injury, but pathologic in case of thrombosis.

Causes

Pathophysiology

Specifically, a thrombus is a blood clot in an intact blood vessel. A thrombus in a large blood vessel will decrease blood flow through that vessel. In a small blood vessel, blood flow may be completely cut-off resulting in death of tissue supplied by that vessel. If a thrombus dislodges and becomes free-floating, it is an embolus.

Some of the conditions which elevate risk of blood clots developing include atrial fibrillation (a form of cardiac arrhythmia), heart valve replacement, a recent heart attack, extended periods of inactivity (see deep venous thrombosis), and genetic or disease-related deficiencies in the blood's clotting abilities.

Preventing blood clots reduces the risk of stroke, heart attack and pulmonary embolism. Heparin and warfarin are often used to inhibit the formation and growth of existing blood clots, thereby allowing the body to shrink and dissolve the blood clots through normal methods (see anticoagulant).

A thrombus differs from a hematoma by:

- Having high hematocrit

- Being non-laminar

- Being soft and friable

- Having an absence of circulation

Virchow's Triad

Virchow's Triad describes the conditions necessary for thrombus formation:

- Changes in vessel wall morphology (e.g. trauma, atheroma)

- Changes in blood flow through the vessel (e.g. valvulitis, aneurysm)

- Changes in blood composition (e.g. leukaemia, hypercoagulability disorders)

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) involves widespread microthrombi formation throughout the majority of the blood vessels. This is due to excessive consumption of coagulation factors and fibrinolysis using all of the body's available platelets and clotting factors. The end result is ischaemic necrosis of the affected tissue/organs and spontaneous bleeding due to the lack of clotting factors. Causes are septicaemia, acute leukaemia, shock, snake bites or severe trauma. Treatment involves the use of fresh, frozen plasma to restore the level of clotting factors in the blood.

Thrombogenecity

Thrombogenicity refers to the tendency of a material in contact with the blood to produce a thrombus, or clot. It not only refers to fixed thrombi but also to emboli, thrombi which have become detached and travel through the bloodstream. Thrombogenicity can also encompass events such as the activation of immune pathways and the complement system. All materials are considered to be thrombogenic with the exception of the endothelial cells which line the vasculature. Certain medical implants appear non-thrombogenic due to high flow rates of blood past the implant, but in reality all are thrombogenic to a degree.

A thrombogenic implant will eventually be covered by a fibrous capsule, the thickness of this capsule can be considered one measure of thrombogenicity, and if extreme can lead to the failure of the implant.

Arterial thrombus

The pathogenic process of arterial thrombosis involves the formation of platelet-rich “white clots” after the rupture of atherosclerotic plaques and exposure of procoagulant material such as lipid-rich macrophages (foam cells), collagen, tissue factor, and/or endothelial breach, in a high shear environment. The exposed material come from within the plaque and also from the activation and aggregation of platelets. Platelet accumulation and fibrin deposition cause an occlusive platelet-rich intravascular thrombus. The growing thrombus increases the degree of narrowing, which may result in extremely high shear rates within the stenotic region. This phenomenon is responsible for a turbulent flow which is developed downstream of the stenosis depending on stenosis geometry and location in the vasculature.[1][2]

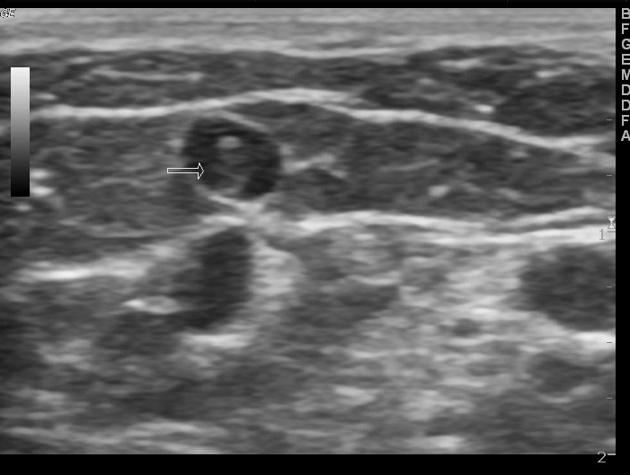

Venous thrombus

The pathophysiology of venous thrombosis or thromboembolism is associated to plasma hypercoagulability triggered by the expression of procoagulant activity, in intact endothelium, from inflammation or reduced/static blood flow resulting in prolonged immobility. Therefore the venous clots are slowly formed involving the formation of fibrin-rich “red clots” which have regions or layers showing substantial erythrocyte incorporation. Finally, the venous thrombi may initiate behind valve pockets, in which the reduced or static flow decreases wall shear stress that normally regulates endothelial cell phenotype.[2] Thus, this phenomenum makes the venous endotelium more likely to develop inappropriate expression of intravascular procoagulant activity and so to trigger venous thromboembolism.[3][4]

|

|

Clinical Significance

Arterial Thrombosis

Venous Thrombosis

- Atrial fibrillation

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Jugular vein thrombosis

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Paget-Schroetter disease

- Portal vein thrombosis

- Pulmonary embolism

- Renal vein thrombosis

Treatment

Thrombolysis is the breakdown of blood clots. It is colloquially referred to as clot busting for this reason. It works by stimulating fibrinolysis by plasmin through infusion of analogs of tissue plasminogen activator, the protein that normally activates plasmin.

References

- ↑ Bark, DL.; Ku, DN. (2010). "Wall shear over high degree stenoses pertinent to atherothrombosis". J Biomech. 43 (15): 2970–7. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.07.011. PMID 20728892. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Wolberg, AS.; Aleman, MM.; Leiderman, K.; Machlus, KR. (2012). "Procoagulant activity in hemostasis and thrombosis: Virchow's triad revisited". Anesth Analg. 114 (2): 275–85. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31823a088c. PMID 22104070. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Machlus, KR.; Cardenas, JC.; Church, FC.; Wolberg, AS. (2011). "Causal relationship between hyperfibrinogenemia, thrombosis, and resistance to thrombolysis in mice". Blood. 117 (18): 4953–63. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-11-316885. PMID 21355090. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Campbell, RA.; Overmyer, KA.; Selzman, CH.; Sheridan, BC.; Wolberg, AS. (2009). "Contributions of extravascular and intravascular cells to fibrin network formation, structure, and stability". Blood. 114 (23): 4886–96. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-06-228940. PMID 19797520. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)