Cholesterol emboli syndrome: Difference between revisions

m Bot: Automated text replacement (-{{SIB}} + & -{{EH}} + & -{{EJ}} + & -{{Editor Help}} + & -{{Editor Join}} +) |

m Robot: Automated text replacement (-{{WikiDoc Cardiology Network Infobox}} +, -<references /> +{{reflist|2}}, -{{reflist}} +{{reflist|2}}) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{SI}} | {{SI}} | ||

{{CMG}} | {{CMG}} | ||

| Line 143: | Line 143: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

===Additional Reading=== | ===Additional Reading=== | ||

Revision as of 15:30, 4 September 2012

| Cholesterol embolism | |

| |

|---|---|

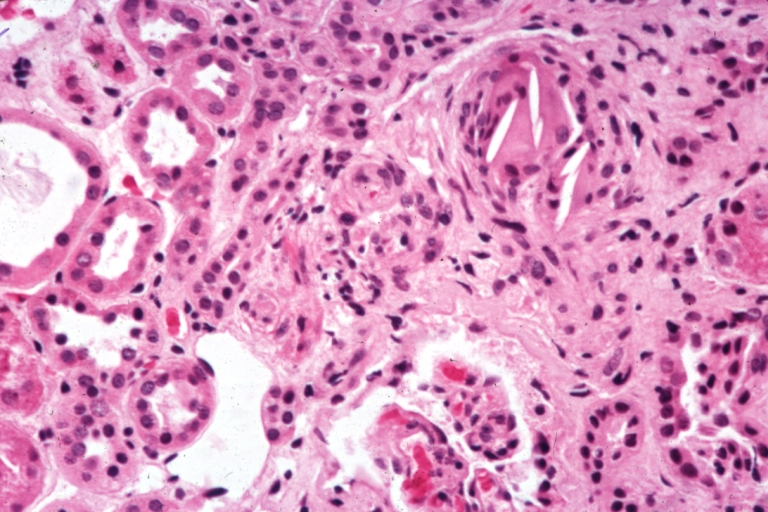

| Kidney: Atheromatous Embolus: Micro H&E med mag good example cholesterol crystals in small artery. Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology | |

| ICD-9 | 445 |

| DiseasesDB | 2567 |

| MeSH | D017700 |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Cholesterol embolism (often cholesterol crystal embolism or atheroembolism, sometimes blue toe or purple toe syndrome or trash foot) occurs when cholesterol is released, usually from an atherosclerotic plaque, and travels along with the bloodsteam (embolism) to other places in the body, where it obstructs blood vessels. Most commonly this causes skin symptoms (usually livedo reticularis), gangrene of the extremities and sometimes renal failure; problems with other organs may arise, depending on the site at which the cholesterol crystals enter the bloodstream.[1] When the kidneys are involved, the disease is referred to as atheroembolic renal disease (AERD).[2] The diagnosis usually involves biopsy (removing a tissue sample) from an affected organ. Cholesterol embolism is treated by removing the cause and with supportive therapy; statin drugs have been found to improve the prognosis.[1] CES is underdiagnosed and may mimic other diseases.

History

The phenomenon of embolisation of cholesterol was first recognized by the Danish physiologist Dr Peter Ludvig Panum.[3] Further pathological evidence that eroded atheroma was the source of emboli came from American pathologist Dr Curtis M. Flory, who reported the phenomenon in 3.4% of a large series of patients with severe atherosclerosis of the aorta.[4][2]

Pathophysiology

Cholesterol emboli occur when atheromatous plaques rupture and release cholesterol crystals, either spontaneously or as a result of iatrogenesis. Cholesterol emboli syndrome (CES) is defined as the occlusion of 55-900 um arterioles by cholesterol crystals after their dislodgment from eroded upstream atheromatous plaques. The occlusion site is subsequently surrounded by intimal tissue, fibrin and platelet thrombi, and foreign-body giant cells.

Epidemiology and Demographics

- Cholesterol emboli syndrome is more common in male patients (~75%) with severe atherosclerotic disease, and often occurs days to weeks after an invasive procedure.

Risk Factors

- Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, history of MI (myocardial infarction)

- Anticoagulation and perhaps thrombolytic therapy – perhaps because overlying thrombi do not form over eroded plaques

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Hypertension

- Aortic aneurysm

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Smoking history

- Male sex

- Age over 55 years

- Vascular procedures

- Invasive angiography, including interventional cardiac catheterizations

- Aortic aneurysm rupture or surgery

- Vascular surgery

Diagnosis

Common Cuases

It is relatively unusual (25%) for cholesterol emboli to occur spontaneously; this usually happens in people with severe atherosclerosis of the large arteries such as the aorta. In the other 75% it is a complication of medical procedures involving the blood vessels, such as vascular surgery or angiography. In coronary catheterization, for instance, the incidence is 1.4%.[5] Furthermore, cholesterol embolism may develop after the commencement of anticoagulants or thrombolytic medication that decrease blood clotting or dissolve blood clots, respectively. They probably lead to cholesterol emboli by removing blood clots that cover up a damaged atherosclerotic plaque; cholesterol-rich debris can then enter the bloodsteam.[2]

Complete Differential diagnosis

Findings on general investigations (such as blood tests) are not specific for cholesterol embolism, which makes diagnosis difficult. The main problem is the distinction between cholesterol embolism and vasculitis (inflammation of the small blood vessels), which may cause very similar symptoms - especially the skin findings and the kidney dysfunction.[2] Worsening kidney function after an angiogram may also be attributed to kidney damage by substances used during the procedure (contrast nephropathy). Other causes that may lead to similar symptoms include ischemic renal failure (kidney dysfunction due to an interrupted blood supply), a group of diseases known as thrombotic microangiopathies and endocarditis (infection of the heart valves with small clumps of infected tissue embolizing through the body).[2]

History and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms experienced in cholesterol embolism depend largely on the organ involved. Non-specific symptoms often described are fever, muscle ache and weight loss. Embolism to the legs causes a mottled appearance and purple discoloration of the toes, smalls infarcts and areas of gangrene due to tissue death that usually appear black, and areas of the skin that assume a marbled pattern known as livedo reticularis.[2]

Kidney involvement leads to the symptoms of renal failure, which are non-specific but usually cause nausea, reduced appetite (anorexia), raised blood pressure (hypertension), and occasionally the various symptoms of electrolyte disturbance such as an irregular heartbeat. Some patients report hematuria (bloody urine) but this may only be detectable on microscopic examination of the urine. Increased amounts of protein in the urine may cause edema (swelling) of the skin (a combination of symptoms known as nephrotic syndrome).[2]

If emboli have spread to the digestive tract, reduced appetite, nausea and vomiting may occur, as well as nonspecific abdominal pain, gastrointestinal hemorrhage (vomiting blood, or admixture of blood in the stool), and occasionally acute pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas).[2]

Both the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system may be involved. Emboli to the brain may cause stroke-like episodes, headache and episodes of loss of vision in one eye (known as amaurosis fugax).[2] Emboli to the eye can be seen by ophthalmoscopy and are known as plaques of Hollenhorst.[6] Emboli to the spinal cord may cause paraparesis (decreased power in the legs) or cauda equina syndrome, a group of symptoms due to loss of function of the distal part of the spinal cord - loss of control over the bladder, rectum and skin sensation around the anus.[2] If the blood supply to a single nerve is interrupted by an embolus, the result is loss of function in the muscles supplied by that nerve; this phenomenon is called a mononeuropathy.[2]

- CES may resemble a systemic vasculitis like PAN, with multiple scattered areas of ischemic damage, with skin, renal, extremity, intestinal, and neurologic manifestations.

- Signs of peripheral ischemia without large vessel disease

Physical Examination

- Chest pain due to myocardial ischemia

- Paradoxical embolus: presence of patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect

- Other rare manifestations include retinal lesions, splenic infarcts, prostatitis, orchitis, hemorrhagic cystitis

- Fever

Abdomen

- Abdominal pain

- Occult blood positive stool due to ischemia of the stomach, small intestine and colon

- Less common manifestations include ischemic pancreatitis, focal liver cell necrosis and acalculous necrotizing cholecystitis.

- Renal failure

- Acute or step-wise worsening function

- Patients may demonstrate focal segmental glomerulosclerosis may be seen, presenting with progressive renal insufficiency, sometimes with significant proteinuria.

Neurologic

- Neurologic abnormalities

- Mononeuritis multiplex

- CNS involvement

Skin

- Cutaneous involvement – cutaneous involvement increases the likelihood of accurate diagnosis.

- Blue toes / nail bed infarctions

- Livedo reticularis – present in up to 50%

- Cyanosis, purpura, tender nodules, ulcerations, gangrene

Laboratory Findings

Blood and urine

Tests for inflammation (C-reactive protein and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate) are typically elevated, and abnormal liver enzymes may be seen.[2] If the kidneys are involved, tests of renal function (such as urea and creatinine) are elevated.[2] The complete blood count may show particularly high numbers of a type of white blood cell known as eosinophils (more than 0.5 billion per liter); this occurs in only 60-80% of cases, so normal eosinophil counts do not rule out the diagnosis.[2][5] Examination of the urine may show red blood cells (occasionally in casts as seen under the microscope) and increased levels of protein; in a third of the cases with kidney involvement, eosinophils can also be detected in the urine.[2] If vasculitis is suspected, complement levels may be determined as reduced levels are often encountered in vasculitis; complement is a group of proteins that forms part of the innate immune system. Complement levels are frequently reduced in cholesterol embolism, limiting the use of this test in the distinction between vasculitis and cholesterol embolism.[7]

- Organ specific damage

- Renal failure - rapidly progressive in many cases greenberg

- Myocardial infarction - serum creatine kinase (CPK) and troponin elevation

- Mesenteric ischemia - Bloody (OB+) stool common

- Stroke

- Full septic picture may ensue

- Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) greenberg

- Microangiopathic hemolysis (disseminated intravascular coagulopathy)

- Hypotension is usually a late finding

Electrolyte and Biomarker Studies

- Peripheral eosinophilia moolenaarneth

- Urinary eosinophilia - usually in patients with cholesterol-renal disease

- May have leukocytosis (even >20K/µL) with left shift

- Hypocomplementemia is common

- Sed rates are nonspecifically elevated

- Thrombocytopenia due to aggregation and complement activation

Other Diagnostic Studies

- Biopsy of lesions may be beneficial

- Biopsy of affected organs shows characteristic changes in about half[5] to 75%[2] the clinically diagnosed cases.

- Biopsy of skin lesions is often revealing in patients with cutaneous involvement.

- Transverse sections of affected arterioles, show occlusion of the lumen by biconvex needle-shaped cholesterol crystals, which dissolve during histologic processing to leave clefts, surrounded by fibrin and platelet thrombi, sometimes in association with foreign-body giant cells and intimal thickening.

Risk Stratification and Prognosis

- Many patients go on to amputation, renal failure, other organ system failure, and/or death.

- Mortality has not been well studied. The diagnosis may be difficult to make, and requires suspicion based upon clinical findings that often mimic other diseases. Therefore, the correct diagnosis is often never made, so the natural history and prognosis of all patients with CES is difficult to ascertain.

- Nevertheless, mortality been reported to be as high as 37-90%, biased by selection and report bias.

- Given the pathogenesis, one would expect a spectrum of disease, with probably significant numbers of subclinical, good prognosis patients.

Treatment

Treatment of an episode of cholesterol emboli is generally symptomatic, i.e. it deals with the symptoms and complications but cannot reverse the phenomenon itself.[5] In kidney failure resulting from cholesterol crystal emboli, statins have been shown to halve the risk of requiring hemodialysis.[1]

- No definitive therapy at this time; supportive care, fluids

- The role of anticoagulation is not clear – some of advocated anticoagulation and others have warned against it.

- Some have advocated lipid-lowering agents.

- Unclear role for glucocorticoids, even when significant eosinophilia is present

- Anecdotal case reports have reported improvement

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Scolari F, Ravani P, Gaggi R; et al. (2007). "The challenge of diagnosing atheroembolic renal disease: clinical features and prognostic factors". Circulation. 116 (3): 298–304. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.680991. PMID 17606842. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Modi KS, Rao VK (2001). "Atheroembolic renal disease". J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12 (8): 1781–7. PMID 11461954. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Panum PL (1862). "Experimentelle Beitrage zur Lehre von der Embolie". Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol (in German). 25: 308–310. doi:10.1007/BF01879803.

- ↑ Flory CM (1945). "Arterial occlusions produced by emboli from eroded aortic atheromatous plaques". Am J Pathol. 21: 549–565. PMC 1934118

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, Masumoto A, Takeshita A (2003). "The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 42 (2): 211–6. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00579-5. PMID 12875753. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Schwarcz TH, Eton D, Ellenby MI, Stelmack T, McMahon TT, Mulder S, Meyer JP, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Durham JR, Flanigan DP; et al. "Hollenhorst plaques: retinal manifestations and the role of carotid endarterectomy". J Vasc Surg. 11 (5): 635–641. PMID 2335833. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Cosio FG, Zager RA, Sharma HM (1985). "Atheroembolic renal disease causes hypocomplementaemia". Lancet. 2 (8447): 118–21. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(85)90225-9. PMID 2862317. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)

Additional Reading

- Rhodes, JM. Cholesterol emboli syndrome. Lancet 1996;347:1641.

- Mayo, RR, et al. Redefining the incidence of clinically detectable atheroembolism. Amer J Med 1996;100:524. PMID 8644764

- Kauffman, MG. Cholesterol emboli syndrome. Outlines in Clinical Medicine, 1997.

- Moolenaar, W, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolization in the Netherlands. Arch Int Med 1996;156:653. PMID 8629877

- Greenberg, A, et al. FSGS associated with cholesterol atheroembolism. Am J Kid Dis 1997;29:334. PMID 9041208

- Sijpkens, Y, et al. Vasculitis due to cholesterol embolism. Am J Med 1997;102:302. PMID 9217601

- Vidt, DG. Cholesterol emboli: a common cause of renal failure. Annu Rev Med 1997;48:375. PMID 9046969

- Moolenaar, W, et al. Cholesterol crystal embolism to the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:1819. PMID 8794801

Acknowledgements

The content on this page was first contributed by: C. Michael Gibson, M.S>, M.D. and Ellison L. Smith, M.D.

External links

- Patient.co.uk - summary

- MedlinePlus - atheroembolic renal disease