Sudden cardiac versus non-cardiac death: Difference between revisions

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

[[Sudden cardiac death]] is a natural, rapid, unexpected death secondary to [[cardiac]] cause or mechanism. [[Sudden cardiac arrest]] is defined as the unexpected cessation of pumping blood into vital organs due to electrical disturbance in the pathway of [[SA node]], [[AV node]], [[Hiss Purkinje fibers]] or pumping failure due to conditions such as [[cardiogenic shock]], [[massive pulmonary thromboembolism]],[[fulminant myocarditis]], [[ruptured left ventricular free wall]]. Without any intervention for immediate restoration of the [[circulation]], biologic death or [[sudden cardiac death]] will happen minutes to weeks after cardiac arrest. [[Sudden cardiac death]] is responsible for 50% of cardiac death annually in the united state. In-hospital [[cardiac arrest]] happens in 290,000 adults annually in the united states. The most common cause of [[sudden cardiac death]] is [[coronary artery disease]] and [[atherosclerosis]] process. The presence of underlying disorders such as [[malignancy]] or [[liver disease]] at the time of cardiac arrest makes the condition worst. Patients with acute [[myocardial infarction]] and [[in-hospital cardiac arrest]] with shockable [[rhythm]] have a better prognosis. Post [[cardiopulmonary resuscitation]] state management should be focused on [[neurologic]] complications, [[hemodynamic]] stability, and [[respiratory]] support. | [[Sudden cardiac death]] is a natural, rapid, unexpected death secondary to [[cardiac]] cause or mechanism. [[Sudden cardiac arrest]] is defined as the unexpected cessation of pumping blood into vital organs due to electrical disturbance in the pathway of [[SA node]], [[AV node]], [[Hiss Purkinje fibers]] or pumping failure due to conditions such as [[cardiogenic shock]], [[massive pulmonary thromboembolism]],[[fulminant myocarditis]], [[ruptured left ventricular free wall]]. Without any intervention for immediate restoration of the [[circulation]], [[biologic death]] or [[sudden cardiac death]] will happen minutes to weeks after [[cardiac arrest]]. [[Sudden cardiac death]] is responsible for 50% of cardiac death annually in the united state. In-hospital [[cardiac arrest]] happens in 290,000 adults annually in the united states. The most common cause of [[sudden cardiac death]] is [[coronary artery disease]] and [[atherosclerosis]] process. The presence of underlying disorders such as [[malignancy]] or [[liver disease]] at the time of cardiac arrest makes the condition worst. Patients with acute [[myocardial infarction]] and [[in-hospital cardiac arrest]] with shockable [[rhythm]] have a better prognosis. Post [[cardiopulmonary resuscitation]] state management should be focused on [[neurologic]] complications, [[hemodynamic]] stability, and [[respiratory]] support. | ||

==Historical Perspective== | ==Historical Perspective== | ||

Revision as of 10:51, 2 February 2021

|

Sudden cardiac death Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Sudden cardiac versus non-cardiac death On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Sudden cardiac versus non-cardiac death |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Sudden cardiac versus non-cardiac death |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Sara Zand, M.D.[2]

Overview

Sudden cardiac death is a natural, rapid, unexpected death secondary to cardiac cause or mechanism. Sudden cardiac arrest is defined as the unexpected cessation of pumping blood into vital organs due to electrical disturbance in the pathway of SA node, AV node, Hiss Purkinje fibers or pumping failure due to conditions such as cardiogenic shock, massive pulmonary thromboembolism,fulminant myocarditis, ruptured left ventricular free wall. Without any intervention for immediate restoration of the circulation, biologic death or sudden cardiac death will happen minutes to weeks after cardiac arrest. Sudden cardiac death is responsible for 50% of cardiac death annually in the united state. In-hospital cardiac arrest happens in 290,000 adults annually in the united states. The most common cause of sudden cardiac death is coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis process. The presence of underlying disorders such as malignancy or liver disease at the time of cardiac arrest makes the condition worst. Patients with acute myocardial infarction and in-hospital cardiac arrest with shockable rhythm have a better prognosis. Post cardiopulmonary resuscitation state management should be focused on neurologic complications, hemodynamic stability, and respiratory support.

Historical Perspective

There is no historical perspective available about sudden cardiac death.

Classification

There are some definitions related to cardiac arrest including:[1]

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| Sudden cardiac death | Sudden and unexpected death within one hour of being symptomatic or whitin 24 hours in asymptomatic patient due to arrhythmia or hemodynamic instability |

| Sudden cardiac arrest | Suddenly cessation of cardiac activity,unresponsive patient with gasping respiration or no respiratory movement and unpalpable pulses due to cardiac etiology such as arrhythmia, pump failure or non cardiac etiology such as trauma, respiratory failure, electrolytes disturbance, drug overdose, drowning, asphexia |

| Aborted cardiac arrest | Unexpected circulatory collapse within one hour of being symptomatic, which is turned back after successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome),SADS (sudden arrhythmic death syndrome) | Structurally normal heart without any specific findings in autopsy or toxicology |

| SUDI (sudden unexplained death in infancy), SUDS (sudden

unexplained death syndrome) |

Sudden death without any specific findings in autopsy in adult (SUDS) or infants less than 1 year (SUDI) |

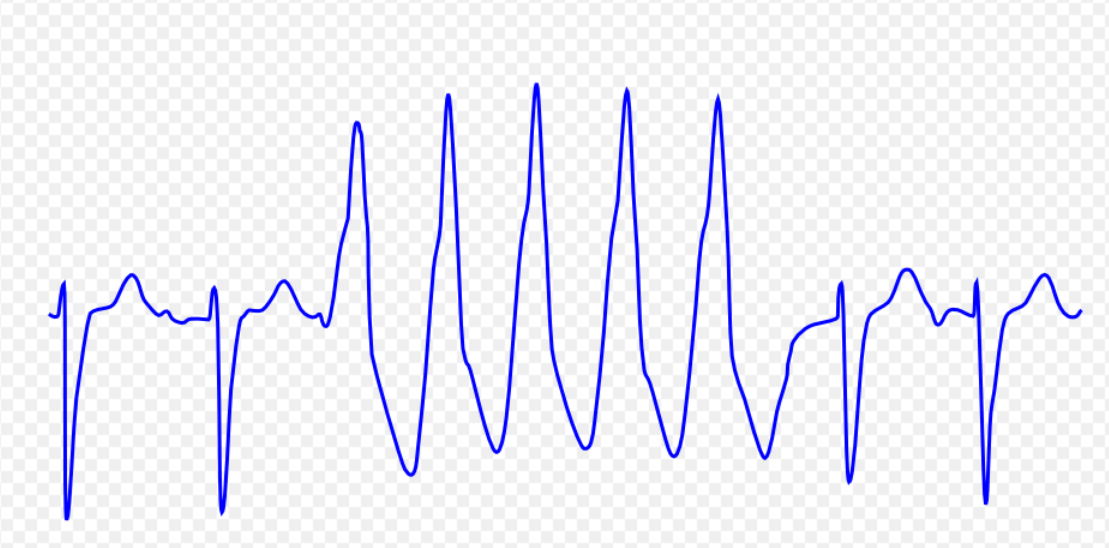

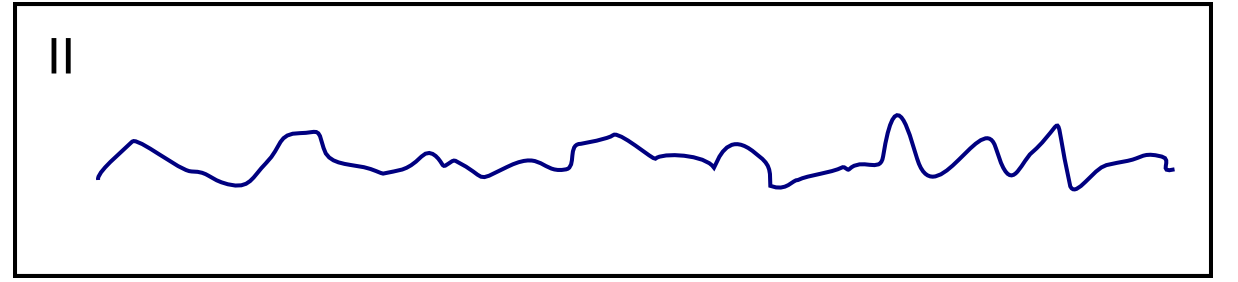

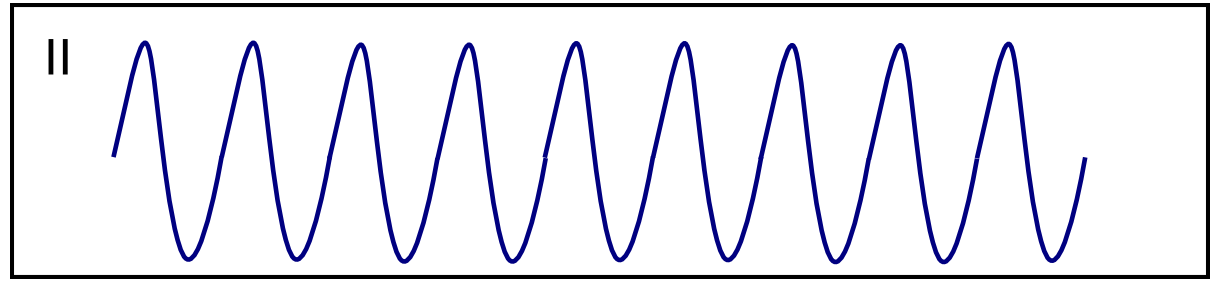

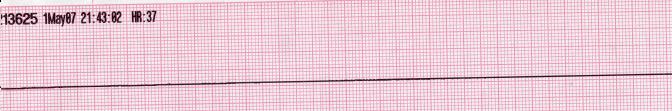

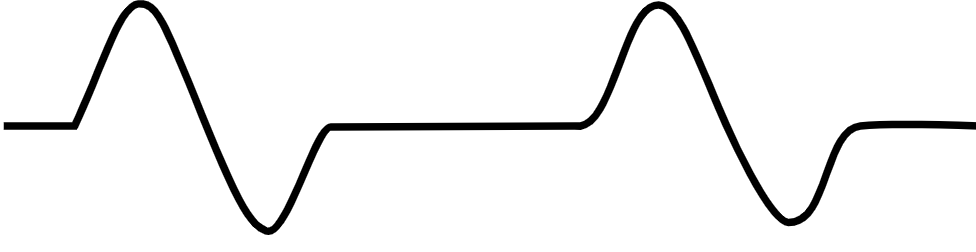

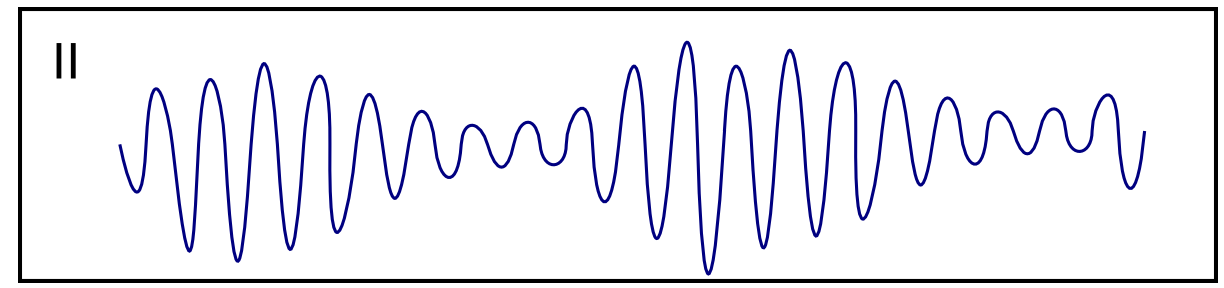

- The table below provides information on the characteristics of sudden cardiac arrest in terms of ECG appearance:

| Classification | Causes | ECG Characteristics | ECG view |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventricular tachycardia [2][3][4][5][6] |

|

| |

| Ventricular fibrillation [8][9][10][11] |

|

| |

| Ventricular flutter [13][14][15] |

|

| |

| Asystole [17][18] |

|

| |

| Pulseless electrical activity [20][21] |

|

|

|

| Torsade de Pointes [23][24][25] |

|

|

Pathophysiology

- The pathogenesis of cardiac arrest is characterized by the myocardial inflammatory process in the setting of atherosclerosis, structural heart disease, genetic disorders, and environmental factors.

- The SCN5A, KCNH2, KCNQ1, RYR2, MYBPC3, PKP2, DSP genes mutation has been associated with the development of inherited causes of cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death.[27][28][29]

| Structural and functional causes of sudden cardiac death | Trigger

| Arrhythmia mechanism

| Fatal arrhythmia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Causes

Sudden cardiac arrest may be caused by :

- Coronary artery abnormality such as coronary atherosclerosis, acute MI, coronary artery embolism, coronary arteritis[28]

- Hypertrophy of myocardium such as HCM, hypertensive heart disease, primary or secondary pulmonary hypertension

- Myocardial disease such as ischemic cardiomyopathy, non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, myocarditis[31]

- Valvular heart disease such as aortic stenosis,aortic insufficiency, mitral valve prolapse, endocarditis [30]

- Congenital heart disease such as congenital septal defect with Eisenmenger physiology[32]

- Abnormality in conducting system such as wolf-Parkinson-white syndrome

- Electrical instability such as (CPVT, LQTS)

Causes of Sudden Death Including Sudden Cardiac Death by Organ System

Differentiating sudden cardiac death from non-cardiac causes

Epidemiology and Demographics

- The prevalence of sudden cardiac death is approximately 1.40 per 100,000 individuals in women to 6.68 per 100.000 individuals in men worldwide.[1]

- In 2015, the incidence of adult in-hospital cardiac arrests was estimated to be 970 cases per 100,000 individuals in the united states.[33]

Age

- Cardiac arrest is more commonly observed within the first year of life due to sudden infant death syndrome and also between 45-75 years old due to increased risk of coronary artery disease.

- There is a significant decrease in sudden cardiac death at age 75 and older due to decreasing risk of coronary artery disease.

Gender

- Men are more commonly affected with sudden cardiac death than women in all age groups.

Race

- Black individuals are more likely to develop cardiac arrest.[34]

Risk Factors

- Common risk factors related to underlying coronary artery disease and inherited causes in the development of sudden cardiac arrest are:[35]

- Hypertension

- Male gender

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hyperlipidemia

- Obesity

- Smoking

- Older age

- Obstructive sleep apnea due to hypoxia

- Early VF (within 48 hours of ACS increasing in-hospital mortality five times)

- Early repolarization patten in early phase of MI[36]

- Family history of sudden death

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

Sudden cardiac arrest occurs due to sudden disturbance in cardiac electrical propagation or failure of the heart to pumping the blood into vital organs.

- Early clinical features include abrupt palpitation, presyncope, syncope, chest pain, dyspnea, hypotension within one hour before terminal event.

- Patients may progress to develop cardiac arrest , sudden collapse, loss of effective circulation, loss of consciousness.

- If left untreated or failed resuscitation, biological death may occur within minutes to weeks.

- Common complications in survivors of cardiac arrest include pneumonia, gastrointestinal bleeding, injuries related to resuscitation, liver function test disturbance, acure renal failure, electrolytes disturbances, seizure.[37]

- Two-thirds of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest admitted in intensive care unit die of neurological complications.

- Most of the in-hospital cardiac death occur due to multiorgans dysfunction and one forth death is due to neurological complications. [38]

- Factors associated poor prognosis after in hospital cardiac arrest include:[39][40]

- Age > 70 years old

- Concomitant underlying disorders such as pneumonia, hypotension, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction

- Non shockable rhythm such as asystole or pulseless electrical activity

- Factors associated with better prognosis after in-hospital cardiac arrest include:

- Early detection of cardiac arrest or being a witness during arrest

- Shockable rhythm such as VF, VT

- Women between 15-45 years old[41]

- Prognosis of in-hospital cardiac arrest is generally better than out of hospital cardiac arrest and the 1-year survival rate of patients who survived to hospital discharge was approximately 25% in the GWTG-R registry.[42].Survival after out of hospital cardiac arrest and in hospital cardiac arrest has continued to improve over time according to the guideline.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

- The diagnosis of sudden cardiac arrest is made when the following diagnostic criteria are met:

- Absence of a palpable pulse of the heart[43]

- Absent carotid pulse

- Gasping respiration or NO respiration

- Loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion

Symptoms

- Symptoms related to arrhythmia or underlying heart disease within one hour before cardiac arrest may include the following:[46]

- Palpitations

- lightheadedness

- syncope

- dyspnea

- chest pain

- cardiac arrest

- Dyspnea at rest or on exertion

- orthopnea

- paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- chest pain, edema

Physical Examination

- Patients with cardiac arrest usually appear cyanotic.

- Physical examination may be remarkable for:

Laboratory Findings

- An elevated concentration of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) predicts has been shown as the predictor of ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death.[47]

Electrocardiogram

An ECG may be helpful in the diagnosis of Sudden cardiac death. Findings on ECG associated with sudden cardiac arrest include:[48]

- Sinus tachycardia (39%)

- Abnormal T-wave inversions (30%)

- Prolonged QT interval (26%)

- Left/right atrial abnormality (22%)

- LVH (17%)

- Abnormal frontal QRS axis (17%)

- Delayed QRS-transition zone in precordial leads (13%)

- Pathological Q waves (13%)

- intraventricular conduction delays (9%)

- Multiple premature ventricular contractions (9%)

- Normal ECG (9%)

2017AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of sudden cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia

| Class I (Level of Evidence: B) |

|

| Class of recommendation | Level of evidence | Recommendation for ECG and exercise tredmile test |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | B | In patients with wide complex tachycardia and hemodynamically stable, 12 leads ECG should be obtained |

| 1 | B | Exercise stress test should be obtained in patients suspected arrhythmia-related exercise such as ischemic heart disease or cathecolaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia |

| 1 | B | In patients with documented ventricular arrhythmia, 12 leads ECG should be obtained during sinus rhythm for evaluation of underlying heart disease |

X-ray

A chest x-ray may be helpful in the diagnosis of the underlying cause of cardiac arrest such as cardiomegally, pulmonary congestion, massive pericardial effusion, widening aorta silhouette.

Echocardiography or Ultrasound

Echocardiography may be helpful in the diagnosis the cause of lethal arrhythmia and sudden cardiac arrest by assessment of the following:[49]

- Regional wall motion abnormality

- Systolic function of left ventricle

- Evidence of myocardial infarction

- Valvular heart disease such as aortic stenosis

- Right ventricular cardiomyopathy

- Pericardial effusion, Tamponade

- Aorta dissection

2017AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of sudden cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia

| Class I (Level of Evidence: B) |

|

CT scan

Cardiac CT scan may be helpful in the diagnosis of the causes of cardiac arrest by evaluation of the following:[50]

- LV volumes

- Ejection fraction

- Cardiac mass

- Anomalous origin of coronary arteries

- Coronary arteries calcification

- Pulmonary embolism

- Aorta dissection

2017AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of sudden cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia

| Class I (Level of Evidence: C) |

|

MRI

Cardiac MRI is an accurate modality for diagnosis of structural and functional causes of cardiac arrest by the evaluation of the following:[51]

- Chamber volumes

- Left ventricular mass

- Left ventricular size, function

- Right ventricular size and function

- Regional wall motion abnormality

2017AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of sudden cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia

| Class IIa (Level of Evidence: C) |

|

Other Imaging Findings

There are no other imaging findings associated with sudden cardiac death.

Other Diagnostic Studies

- In survivors of sudden cardiac death due to lethal arrhythmia from ischemic heart disease, coronary angiography and probable revascularization is recommended.[52]

- Electrophysiology study is recommended for induction of bradyarrhythmia ,ventricular tachyarrhythmia, determination the indication for ICD implantation in dilated cardiomyopathy,ARVC, HCM.

- Electrophysiology study is not recommended in long QT syndrome (LQTS), cathecolaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT), short QTsyndrome (SQTS)..[53]

2017AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of sudden cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia

| Class I, Level of evidence:B |

| In patients who recovered from SCA due to ventricular arrhythmia suspected ischemic heart disease, coronary angiography and probabley revascularization is recommmended |

| Class I, Level of evidence:C |

| In patients with anomalous origin of a coronary artery leading ventricular arrhythmia or SCA, repair or revascularization is recommended |

| Class IIa, Level of evidence:B |

| In patients with ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy or congenital heart disease presented with syncope arrhythmia and do not meet criteria for primary prevention ICD, an electrophysiological study is recommended for assessing the risk of sustained VT |

| Class III, Level of evidence:B |

| In patients who meet criteria for ICD implantation, an electrophysiological study is not recommended for only inducing ventricular arrhythmia |

| Class III, Level of evidence:B |

| An electrophysiological study is not recommended for risk stratification for ventricular arrhythmia in patients with Long QT syndrome, short QT syndrome, cathecolaminergic polymorphic ventricular arrhythmia |

| Class I (Level of Evidence: C) |

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- The mainstay of therapy for patients with cardiac arrest is starting cardiopulmonary resuscitation with minimizing interruption in chest compression.[1][53]

- The rhythm should be reassessed. If the rhythm is VF orpulseless VT, the shock should be delivered immediately.

- If the rhythm is asystole or pulseless electrical activity (PEA), CPR should be resumed.

- Advanced life support (ALS) should be kept with minimizing interruption in chest compression including:

- advanced airway

- Continuous chest compressions

- after placing an advanced airway

- capnography

- IV/IO access

- vasopressors, antiarrhythmics therapy

- Correcting reversible causes including hypoxia, hypovolemia,hypothermia, hyperkalemia, hypokalemia,acidosis, tension pneumothorax, tamponade, toxins (benzodiazepines, alcohol, opiates, tricyclics, barbiturates, betablockers, calcium channel blockers)

- The followings should be considered immediately in post cardiac arrest patients:

- 12–lead ECG

- Perfusion/reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction

- Oxygenation and ventilation

- Temperature control

- Treatment of reversible causes

- Management of patients in post-cardiac arrest status include:

- Treatment of the underlying disorder

- Hemodynamic stability

- Respiratory support

- Controlling the neurologic complications

2017AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of sudden cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia

| Recommendations for management of cardiac arrest |

| CPR (Class I, Level of Evidence A): |

|

❑ CPR should be done according to basic and advanced cardiovascular life support algorithms |

| Amiodarone (Class I, Level of Evidence A) : |

|

❑ In the recurrence of ventricular arrhythmia after maximum energy shock delivery and unstable hemodynamic, amiodarone should de infused |

| Direct current cardioversion : (Class I, Level of Evidence A) |

|

❑ In ventricular arrhythmia and unstable hemodynamic, direct current cardioversion should be delivered |

| Revascularization:(Class I, Level of Evidence B) |

|

❑ In patients with polymorphic VT and VF and evidence of acute STEMI in ECG, coronary angiography and emergency revascularization is advised |

| Wide QRS tachycardia: (Class I, Level of Evidence C) |

|

❑ Wide QRS tachycardia should be considered as VT if the diagnosis is unclear |

| Intravenous procainamide (Class 2a, Level of Evidence A): |

|

❑ In hemodynamically stable VT, intravenous procainamide is recommended |

| Intravenous lidocaine : (Class 2a, Level of Evidence B) |

|

❑ Lidocaine is recommended in witness cardiac arrest due to polymorphic VT, VF unresponsed to CPR, defibrillation or vasopressor therapy |

| Intravenous betablocker : (Class 2a, Level of Evidence B) |

|

❑ In polymorphic VT due to myocardial ischemia, intravenous betablocker maybe helpful |

| Intravenous Epinephrine : (Class 2b, Level of Evidence A) |

|

❑ In cardiac arrest administration of 1 mg epinephrine every 3-5 minutes during CPR is recommended |

| Intravenous amiodarone : (Class 2b, Level of Evidence B) |

|

❑ In hemodynamic stable VT, infusion amiodarone or sotalole maybe considered |

| High dose of intravenous epinephrine : (Class III , Level of Evidence A) |

|

❑ In cardiac arrest, administration of high dose epinephrine>1 mg bolouses is not beneficial |

| Intravenous amiodarone : (Class III , Level of Evidence B) |

|

❑In acute myocardial infarction, prophylactic administration of lidocaine or amiodarone for prevention of VT is harmful |

| Intravenous verapamil, diltiazem : (Class III , Level of Evidence C) |

|

❑ In a wide QRS tachycardia with unknown origin, administration of verapamil and diltiazem is harmful |

| Sustained monomorphic VT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hemodynamic stability | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stable | Unstable | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12-Lead ECG, history, physical exam | Dirrect current cardioversion,ACLS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notifying disease causing VT | Cardioversion(class1) | VT termination | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Structural heart disease | Intravenous procainamide (class2a) | Yes, therapy of underlying heart disease | NO, cardioversion (class1) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NO, Ideopathic VT | Intravenous amiodarone or sotalole (class2b) | VT termination | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Verapamil sensitive VT: Verapamil outflow tract VT: betablocker (class2a) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Effective | Non effective: cardioversion | Yes,therapy of underlying heart disease | NO, Sedation ,anesthesia, reassess antiarrhythmic therapy, repeating cardioversion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Therapy to prevent recurrence of VT | No VT termination | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catheter ablation (class1) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catheter ablation (class1) | Verapamil , betablocker (class2a) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Intervention

Catheter ablation can only be performed for patients with sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia based on these characteristics:

- Incessant VT or electrical storm due to myocardial scar tissue

- Sustained VT and recurrent ICD shock in ischemic heart disease

Prevention

- Effective measures for the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in individuals who are at risk of SCD but have not yet experienced an aborted cardiac arrest or life-threatening arrhythmias include ICD implantation based on the guideline.[53]

- Secondary prevention strategy following aborted sudden cardiac death include revascularization, ICD implantation.

2017AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of sudden cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia

Abbreviations:

MI: Myocardial infarction;

VT: Ventricular tachycardia;

VF: Ventricular fibrillation;

LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction;

ICD: Intracardiac defibrillation;

NYHA: New York Heart Association functional classification;

LVAD: Left ventricular assist device;

EPS: Electrophysiology study

| Recommendations for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in ischemic heart disease |

| ICD implantation (Class I, Level of Evidence A): |

|

❑ In patients with LVEF≤ 35% and NYHA class 2,3 heart failure despite medical therapy, at least 40 days post MI or 90 days post revascularization with life expectancy > 1 year |

| ICD implantation (Class I, Level of Evidence B) : |

|

❑ In patients with LVEF ≤ 40% and nonsustained VT due to prior MI or VT ,VF inducible in EPS with life expectancy >1 year |

| ICD implantation : (Class IIa, Level of Evidence B) |

|

❑ In patients with NYHA class 4 who are candidates for cardiac transplantation or LVAD with life expectancy > 1 year |

| (Class III, Level of Evidence C) |

|

❑ ICD is not beneficial in patients with NYHA class 4 despite optimal medical therapy who are not candidates for cardiac transplantation or LVAD |

Abbreviations:

IHD: Ischemic heart disease;

VT: Ventricular tachycardia;

SCD: Sudden cardiac death;

SCA: Sudden cardiac arrest;

ICD: Intracardiac defibrillation;

EPS: Electrophysiologic study

| Secondary prevention in patients with IHD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SCA survivor or sustained monomorph VT | Cardiac syncope | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ischemia | LVEF≤35% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes: revascularization, reassessment about SCD risk (class1) | NO:ICD candidate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes:ICD (class1) | NO: medical therapy (class1) | Yes:ICD (CLASS1) | NO:EP study (class 2a) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ventriculat arrhythmia induction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes: ICD (class1) | NO: monitoring | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Priori, Silvia G.; Blomström-Lundqvist, Carina; Mazzanti, Andrea; Blom, Nico; Borggrefe, Martin; Camm, John; Elliott, Perry Mark; Fitzsimons, Donna; Hatala, Robert; Hindricks, Gerhard; Kirchhof, Paulus; Kjeldsen, Keld; Kuck, Karl-Heinz; Hernandez-Madrid, Antonio; Nikolaou, Nikolaos; Norekvål, Tone M.; Spaulding, Christian; Van Veldhuisen, Dirk J. (2015). "2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death". European Heart Journal. 36 (41): 2793–2867. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv316. ISSN 0195-668X.

- ↑ Ajijola, Olujimi A.; Tung, Roderick; Shivkumar, Kalyanam (2014). "Ventricular tachycardia in ischemic heart disease substrates". Indian Heart Journal. 66: S24–S34. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2013.12.039. ISSN 0019-4832.

- ↑ Meja Lopez, Eliany; Malhotra, Rohit (2019). "Ventricular Tachycardia in Structural Heart Disease". Journal of Innovations in Cardiac Rhythm Management. 10 (8): 3762–3773. doi:10.19102/icrm.2019.100801. ISSN 2156-3977.

- ↑ Coughtrie, Abigail L; Behr, Elijah R; Layton, Deborah; Marshall, Vanessa; Camm, A John; Shakir, Saad A W (2017). "Drugs and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia risk: results from the DARE study cohort". BMJ Open. 7 (10): e016627. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016627. ISSN 2044-6055.

- ↑ El-Sherif, Nabil (2001). "Mechanism of Ventricular Arrhythmias in the Long QT Syndrome: On Hermeneutics". Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 12 (8): 973–976. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00973.x. ISSN 1045-3873.

- ↑ de Riva, Marta; Watanabe, Masaya; Zeppenfeld, Katja (2015). "Twelve-Lead ECG of Ventricular Tachycardia in Structural Heart Disease". Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 8 (4): 951–962. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002847. ISSN 1941-3149.

- ↑ ECG found in of https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ Koplan BA, Stevenson WG (March 2009). "Ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death". Mayo Clin. Proc. 84 (3): 289–97. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61149-X. PMC 2664600. PMID 19252119.

- ↑ Maury P, Sacher F, Rollin A, Mondoly P, Duparc A, Zeppenfeld K, Hascoet S (May 2017). "Ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in tetralogy of Fallot". Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 110 (5): 354–362. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2016.12.006. PMID 28222965.

- ↑ Saumarez RC, Camm AJ, Panagos A, Gill JS, Stewart JT, de Belder MA, Simpson IA, McKenna WJ (August 1992). "Ventricular fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is associated with increased fractionation of paced right ventricular electrograms". Circulation. 86 (2): 467–74. doi:10.1161/01.cir.86.2.467. PMID 1638716.

- ↑ Bektas, Firat; Soyuncu, Secgin (2012). "Hypokalemia-induced Ventricular Fibrillation". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 42 (2): 184–185. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.079. ISSN 0736-4679.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ Thies, Karl-Christian; Boos, Karin; Müller-Deile, Kai; Ohrdorf, Wolfgang; Beushausen, Thomas; Townsend, Peter (2000). "Ventricular flutter in a neonate—severe electrolyte imbalance caused by urinary tract infection in the presence of urinary tract malformation". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 18 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(99)00161-4. ISSN 0736-4679.

- ↑ Koster, Rudolph W.; Wellens, Hein J.J. (1976). "Quinidine-induced ventricular flutter and fibrillation without digitalis therapy". The American Journal of Cardiology. 38 (4): 519–523. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(76)90471-9. ISSN 0002-9149.

- ↑ Dhurandhar RW, Nademanee K, Goldman AM (1978). "Ventricular tachycardia-flutter associated with disopyramide therapy: a report of three cases". Heart Lung. 7 (5): 783–7. PMID 250503.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ ACLS: Principles and Practice. p. 71-87. Dallas: American Heart Association, 2003. ISBN 0-87493-341-2.

- ↑ ACLS for Experienced Providers. p. 3-5. Dallas: American Heart Association, 2003. ISBN 0-87493-424-9.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care - Part 7.2: Management of Cardiac Arrest." Circulation 2005; 112: IV-58 - IV-66.

- ↑ Foster B, Twelve Lead Electrocardiography, 2nd edition, 2007

- ↑ ECG found in wikimedia Commons

- ↑ Li M, Ramos LG (July 2017). "Drug-Induced QT Prolongation And Torsades de Pointes". P T. 42 (7): 473–477. PMC 5481298. PMID 28674475.

- ↑ Sharain, Korosh; May, Adam M.; Gersh, Bernard J. (2015). "Chronic Alcoholism and the Danger of Profound Hypomagnesemia". The American Journal of Medicine. 128 (12): e17–e18. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.051. ISSN 0002-9343.

- ↑ Khan IA (2001). "Twelve-lead electrocardiogram of torsades de pointes". Tex Heart Inst J. 28 (1): 69. PMC 101137. PMID 11330748.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ Osman, Junaida; Tan, Shing Cheng; Lee, Pey Yee; Low, Teck Yew; Jamal, Rahman (2019). "Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD) – risk stratification and prediction with molecular biomarkers". Journal of Biomedical Science. 26 (1). doi:10.1186/s12929-019-0535-8. ISSN 1423-0127.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Mehta, Davendra; Curwin, Jay; Gomes, J. Anthony; Fuster, Valentin (1997). "Sudden Death in Coronary Artery Disease". Circulation. 96 (9): 3215–3223. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.96.9.3215. ISSN 0009-7322.

- ↑ Akhtar, Masood (1991). "Sudden Cardiac Death: Management of High-Risk Patients". Annals of Internal Medicine. 114 (6): 499. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-114-6-499. ISSN 0003-4819.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Basso, Cristina; Perazzolo Marra, Martina; Rizzo, Stefania; De Lazzari, Manuel; Giorgi, Benedetta; Cipriani, Alberto; Frigo, Anna Chiara; Rigato, Ilaria; Migliore, Federico; Pilichou, Kalliopi; Bertaglia, Emanuele; Cacciavillani, Luisa; Bauce, Barbara; Corrado, Domenico; Thiene, Gaetano; Iliceto, Sabino (2015). "Arrhythmic Mitral Valve Prolapse and Sudden Cardiac Death". Circulation. 132 (7): 556–566. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016291. ISSN 0009-7322.

- ↑ . doi:10.1080/2F20961790.2019.1595352. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Yap, Sing-Chien; Harris, Louise (2014). "Sudden cardiac death in adults with congenital heart disease". Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy. 7 (12): 1605–1620. doi:10.1586/erc.09.153. ISSN 1477-9072.

- ↑ Holmberg, Mathias J.; Ross, Catherine E.; Fitzmaurice, Garrett M.; Chan, Paul S.; Duval-Arnould, Jordan; Grossestreuer, Anne V.; Yankama, Tuyen; Donnino, Michael W.; Andersen, Lars W.; Chan, Paul; Grossestreuer, Anne V.; Moskowitz, Ari; Edelson, Dana; Ornato, Joseph; Berg, Katherine; Peberdy, Mary Ann; Churpek, Matthew; Kurz, Michael; Starks, Monique Anderson; Girotra, Saket; Perman, Sarah; Goldberger, Zachary; Guerguerian, Anne-Marie; Atkins, Dianne; Foglia, Elizabeth; Fink, Ericka; Lasa, Javier J.; Roberts, Joan; Bembea, Melanie; Gaies, Michael; Kleinman, Monica; Gupta, Punkaj; Sutton, Robert; Sawyer, Taylor (2019). "Annual Incidence of Adult and Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest in the United States". Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 12 (7). doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005580. ISSN 1941-7713.

- ↑ Becker, Lance B.; Han, Ben H.; Meyer, Peter M.; Wright, Fred A.; Rhodes, Karin V.; Smith, David W.; Barrett, John (1993). "Racial Differences in the Incidence of Cardiac Arrest and Subsequent Survival". New England Journal of Medicine. 329 (9): 600–606. doi:10.1056/NEJM199308263290902. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Adabag AS, Luepker RV, Roger VL, Gersh BJ (April 2010). "Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology and risk factors". Nat Rev Cardiol. 7 (4): 216–25. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2010.3. PMC 5014372. PMID 20142817.

- ↑ Naruse, Yoshihisa; Tada, Hiroshi; Harimura, Yoshie; Hayashi, Mayu; Noguchi, Yuichi; Sato, Akira; Yoshida, Kentaro; Sekiguchi, Yukio; Aonuma, Kazutaka (2012). "Early Repolarization Is an Independent Predictor of Occurrences of Ventricular Fibrillation in the Very Early Phase of Acute Myocardial Infarction". Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 5 (3): 506–513. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.111.966952. ISSN 1941-3149.

- ↑ Bjork, Randall J. (1982). "Medical Complications of Cardiopulmonary Arrest". Archives of Internal Medicine. 142 (3): 500. doi:10.1001/archinte.1982.00340160080018. ISSN 0003-9926.

- ↑ . doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.01.031. Epub 2019 Jan 30. Check

|doi=value (help). Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Chan, Paul S. (2012). "A Validated Prediction Tool for Initial Survivors of In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest". Archives of Internal Medicine. 172 (12): 947. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2050. ISSN 0003-9926.

- ↑ Ebell MH, Afonso AM (October 2011). "Pre-arrest predictors of failure to survive after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis". Fam Pract. 28 (5): 505–15. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmr023. PMID 21596693.

- ↑ Topjian AA, Localio AR, Berg RA, Alessandrini EA, Meaney PA, Pepe PE, Larkin GL, Peberdy MA, Becker LB, Nadkarni VM (May 2010). "Women of child-bearing age have better inhospital cardiac arrest survival outcomes than do equal-aged men". Crit Care Med. 38 (5): 1254–60. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8ca43. PMC 3934212. PMID 20228684.

- ↑ Virani, Salim S.; Alonso, Alvaro; Benjamin, Emelia J.; Bittencourt, Marcio S.; Callaway, Clifton W.; Carson, April P.; Chamberlain, Alanna M.; Chang, Alexander R.; Cheng, Susan; Delling, Francesca N.; Djousse, Luc; Elkind, Mitchell S.V.; Ferguson, Jane F.; Fornage, Myriam; Khan, Sadiya S.; Kissela, Brett M.; Knutson, Kristen L.; Kwan, Tak W.; Lackland, Daniel T.; Lewis, Tené T.; Lichtman, Judith H.; Longenecker, Chris T.; Loop, Matthew Shane; Lutsey, Pamela L.; Martin, Seth S.; Matsushita, Kunihiro; Moran, Andrew E.; Mussolino, Michael E.; Perak, Amanda Marma; Rosamond, Wayne D.; Roth, Gregory A.; Sampson, Uchechukwu K.A.; Satou, Gary M.; Schroeder, Emily B.; Shah, Svati H.; Shay, Christina M.; Spartano, Nicole L.; Stokes, Andrew; Tirschwell, David L.; VanWagner, Lisa B.; Tsao, Connie W. (2020). "Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 141 (9). doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. ISSN 0009-7322.

- ↑ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 16th Edition, The McGraw-Hill Companies, ISBN 0-07-140235-7

- ↑ Zimetbaum, Peter; Josephson, Mark E. (1998). "Evaluation of Patients with Palpitations". New England Journal of Medicine. 338 (19): 1369–1373. doi:10.1056/NEJM199805073381907. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Noda, Takashi; Shimizu, Wataru; Taguchi, Atsushi; Aiba, Takeshi; Satomi, Kazuhiro; Suyama, Kazuhiro; Kurita, Takashi; Aihara, Naohiko; Kamakura, Shiro (2005). "Malignant Entity of Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation and Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Initiated by Premature Extrasystoles Originating From the Right Ventricular Outflow Tract". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 46 (7): 1288–1294. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.077. ISSN 0735-1097.

- ↑ Marijon E, Uy-Evanado A, Dumas F, Karam N, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, Narayanan K, Gunson K, Jui J, Jouven X, Chugh SS (January 2016). "Warning Symptoms Are Associated With Survival From Sudden Cardiac Arrest". Ann Intern Med. 164 (1): 23–9. doi:10.7326/M14-2342. PMC 5624713. PMID 26720493.

- ↑ Scott, Paul A.; Barry, James; Roberts, Paul R.; Morgan, John M. (2009). "Brain natriuretic peptide for the prediction of sudden cardiac death and ventricular arrhythmias: a meta-analysis". European Journal of Heart Failure. 11 (10): 958–966. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfp123. ISSN 1388-9842.

- ↑ Jayaraman, Reshmy; Reinier, Kyndaron; Nair, Sandeep; Aro, Aapo L.; Uy-Evanado, Audrey; Rusinaru, Carmen; Stecker, Eric C.; Gunson, Karen; Jui, Jonathan; Chugh, Sumeet S. (2018). "Risk Factors of Sudden Cardiac Death in the Young". Circulation. 137 (15): 1561–1570. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031262. ISSN 0009-7322.

- ↑ Parker, Brian K.; Salerno, Alexis; Euerle, Brian D. (2018). "The Use of Transesophageal Echocardiography During Cardiac Arrest Resuscitation: A Literature Review". Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 38 (5): 1141–1151. doi:10.1002/jum.14794. ISSN 0278-4297.

- ↑ . doi:10.1016/2Fj.radcr.2019.03.007. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Zareba, Wojciech; Zareba, Karolina M. (2017). "Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in Sudden Cardiac Arrest Survivors". Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 10 (12). doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007290. ISSN 1941-9651.

- ↑ Lemkes, Jorrit S.; Janssens, Gladys N.; van der Hoeven, Nina W.; Jewbali, Lucia S. D.; Dubois, Eric A.; Meuwissen, Martijn M.; Rijpstra, Topm A.; Bosker, Hans A.; Blans, Michiel J.; Bleeker, Gabe B.; Baak, Remon R.; Vlachojannis, George J.; Eikemans, Bob J. W.; van der Harst, Pim; van der Horst, Iwan C. C.; Voskuil, Michiel; van der Heijden, Joris J.; Beishuizen, Albertus; Stoel, Martin; Camaro, Cyril; van der Hoeven, Hans; Henriques, Jose P.; Vlaar, Alexander P. J.; Vink, Maarten A.; van den Bogaard, Bas; Heestermans, Ton A. C. M.; de Ruijter, Wouter; Delnoij, Thijs S. R.; Crijns, Harry J. G. M.; Jessurun, Gillian A. J.; Oemrawsingh, Pranobe V.; Gosselink, Marcel T. M.; Plomp, Koos; Magro, Michael; Elbers, Paul W. G.; Spoormans, Eva M.; van de Ven, Peter M.; Oudemans-van Straaten, Heleen M.; van Royen, Niels (2020). "Coronary Angiography After Cardiac Arrest Without ST Segment Elevation". JAMA Cardiology. 5 (12): 1358. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3670. ISSN 2380-6583.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Al-Khatib, Sana M.; Stevenson, William G.; Ackerman, Michael J.; Bryant, William J.; Callans, David J.; Curtis, Anne B.; Deal, Barbara J.; Dickfeld, Timm; Field, Michael E.; Fonarow, Gregg C.; Gillis, Anne M.; Granger, Christopher B.; Hammill, Stephen C.; Hlatky, Mark A.; Joglar, José A.; Kay, G. Neal; Matlock, Daniel D.; Myerburg, Robert J.; Page, Richard L. (2018). "2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death". Circulation. 138 (13). doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000549. ISSN 0009-7322.

Overview

The term sudden cardiac death refers to natural death from cardiac causes, heralded by abrupt loss of consciousness within one hour of the onset of acute symptoms.[1] Other forms of sudden death may be noncardiac in origin and are therefore termed sudden death rather than sudden cardiac death. Examples of this include respiratory arrest (such as due to airway obstruction, which may be seen in cases of choking or asphyxiation), toxicity or poisoning, anaphylaxis, or trauma.[2]

It is important to make a distinction between this term and the related term cardiac arrest, which refers to cessation of cardiac pump function which may be reversible (i.e., may not be fatal). The phrase Sudden Cardiac Death is a public health concept incorporating the features of natural, rapid, and unexpected. It does not specifically refer to the mechanism or cause of death. Although the most frequent underlying cause of Sudden Cardiac Death is Coronary Artery Disease, other categories of causes are listed below.

Cardiac Arrest as a Subtype of Sudden Death

A cardiac arrest, also known as cardiorespiratory arrest, cardiopulmonary arrest or circulatory arrest, is the abrupt cessation of normal circulation of the blood due to failure of the heart to contract effectively during systole.[3]

"Arrested" blood circulation prevents delivery of oxygen to all parts of the body. Cerebral hypoxia, or lack of oxygen supply to the brain, causes victims to lose consciousness and to stop normal breathing. Brain injury is likely if cardiac arrest is untreated for more than 5 minutes,[4] To improve survival and neurological recovery immediate response is paramount.[5]

Cardiac arrest is a medical emergency that, in certain groups of patients, is potentially reversible if treated early enough (See Reversible Causes, below). When unexpected cardiac arrest leads to death this is called sudden cardiac death (SCD)[3]. The primary first-aid treatment for cardiac arrest is cardiopulmonary resuscitation (commonly known as CPR) to provide circulatory support until availability of definitive medical treatment, which will vary dependant on the rhythm the heart is exhibiting, but often requires defibrillation.

FDA Guidance re Classification and Types of Cardiovascular and Non-Cardiovascular Death

Definition of Cardiovascular Death [6]

The determination of the specific cause of cardiovascular death is complicated by the fact that we are particularly interested in one underlying cause of death (acute myocardial infarction (AMI)) and several modes of death (arrhythmia and heart failure/low output). It is noted that heart attack-related deaths are manifested as sudden death or heart failure, so these events need to be carefully defined. Cardiovascular death includes death resulting from an acute myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death, death due to heart failure, death due to stroke, and death due to other cardiovascular causes, as follows:

1.Death due to Acute Myocardial Infarction

This refers to a death by any mechanism (arrhythmia, heart failure, low output) within 30 days after a myocardial infarction (MI) related to the immediate consequences of the myocardial infarction, such as progressive congestive heart failure (CHF), inadequate cardiac output, or recalcitrant arrhythmia. If these events occur after a “break” (e.g., a CHF and arrhythmia free period of at least a week), they should be designated by the immediate cause, even though the MI may have increased the risk of that event (e.g., late arrhythmic death becomes more likely after an acute myocardial infarction (AMI)). The acute myocardial infarction should be verified to the extent possible by the diagnostic criteria outlined for acute myocardial infarction or by autopsy findings showing recent myocardial infarction or recent coronary thrombus. Sudden cardiac death, if accompanied by symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia, new ST elevation, new LBBB, or evidence of fresh thrombus by coronary angiography and/or at autopsy should be considered death resulting from an acute myocardial infarction, even if death occurs before blood samples or 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) could be obtained, or at a time before the appearance of cardiac biomarkers in the blood.

Death resulting from a procedure to treat a myocardial infarction (percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), or to treat a complication resulting from myocardial infarction, should also be considered death due to acute MI.

Death resulting from a procedure to treat myocardial ischemia (angina) or death due to a myocardial infarction that occurs as a direct consequence of a cardiovascular investigation/procedure/operation should be considered as a death due to other cardiovascular causes.

2.Sudden Cardiac Death

This refers to a death that occurs unexpectedly, not following an acute AMI, and includes the following deaths:

- a. Death witnessed and instantaneous without new or worsening symptoms

- b. Death witnessed within 60 minutes of the onset of new or worsening cardiac symptoms, unless the symptoms suggest AMI

- c. Death witnessed and attributed to an identified arrhythmia (e.g., captured on an electrocardiographic (ECG) recording, witnessed on a monitor, or unwitnessed but found on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator review)

- d. Death after unsuccessful resuscitation from cardiac arrest

- e. Death after successful resuscitation from cardiac arrest and without identification of a non-cardiac etiology (Post-Cardiac Arrest Syndrome)

- f. Unwitnessed death without other cause of death (information regarding the patient’s clinical status preceding death should be provided, if available)

General Considerations

- A subject seen alive and clinically stable 12-24 hours prior to being found dead without any evidence or information of a specific cause of death should be classified as :sudden cardiac death.”. Typical scenarios include

- Subject well the previous day but found dead in bed the next day

- Subject found dead at home on the couch with the television on

- Deaths for which there is no information beyond “Patient found dead at home” may be classified as “death due to other cardiovascular causes” or in some trials, “undetermined cause of death.” Please see Definition of Undetermined Cause of Death, below, for full details.

3. Death due to Heart Failure or Cardiogenic Shock

This refers to a death occurring in the context of clinically worsening symptoms and/or signs of heart failure (see Chapter 7) without evidence of another cause of death and not following an AMI. Note that deaths due to heart failure can have various etiologies, including one or more AMIs (late effect), ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, or valve disease.

Death due to Heart Failure or Cardiogenic shock should include sudden death occurring during an admission for worsening heart failure as well as death from progressive heart failure or cardiogenic shock following implantation of a mechanical assist device.

New or worsening signs and/or symptoms of congestive heart failure (CHF) include any of the following:

- a. New or increasing symptoms and/or signs of heart failure requiring the initiation of, or an increase in, treatment directed at heart failure or occurring in a patient already receiving maximal therapy for heart failure

- b. Heart failure symptoms or signs requiring continuous intravenous therapy or chronic oxygen administration for hypoxia due to pulmonary edema

- c. Confinement to bed predominantly due to heart failure symptoms

- d. Pulmonary edema sufficient to cause tachypnea and distress not occurring in the context of an acute myocardial infarction, worsening renal function, or as the consequence of an arrhythmia occurring in the absence of worsening heart failure

- e. Cardiogenic shock not occurring in the context of an acute myocardial infarction or as the consequence of an arrhythmia occurring in the absence of worsening heart failure

Cardiogenic shock is defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 90 mm Hg for greater than 1 hour, not responsive to fluid resuscitation and/or heart rate correction, and felt to be secondary to cardiac dysfunction and associated with at least one of the following signs of hypoperfusion:

- Cool, clammy skin or

- Oliguria (urine output < 30 mL/hour) or

- Altered sensorium or

- Cardiac index < 2.2 L/min/m2

Cardiogenic shock can also be defined if SBP < 90 mm Hg and increases to ≥ 90 mm Hg in less than 1 hour with positive inotropic or vasopressor agents alone and/or with mechanical support.

General Considerations

Heart failure may have a number of underlying causes, including acute or chronic ischemia, structural heart disease (e.g. hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), and valvular heart disease. Where treatments are likely to have specific effects, and it is likely to be possible to distinguish between the various causes, then it may be reasonable to separate out the relevant treatment effects. For example, obesity drugs such as fenfluramine (pondimin) and dexfenfluramine (redux) were found to be associated with the development of valvular heart disease and pulmonary hypertension. In other cases, the aggregation implied by the definition above may be more appropriate.

4.Death due to Stroke

This refers to death occurring up to 30 days after a stroke that is either due to the stroke or caused by a complication of the stroke.

5.Death due to Other Cardiovascular Causes

This refers to a cardiovascular death not included in the above categories (e.g. dysrhythmia unrelated to sudden cardiac death, pulmonary embolism, cardiovascular intervention (other than one related to an AMI), aortic aneurysm rupture, or peripheral arterial disease). Mortal complications of cardiac surgery or non-surgical revascularization should be classified as cardiovascular deaths.

Definition of Non-Cardiovascular Death

Non-cardiovascular death is defined as any death that is not thought to be due to a cardiovascular cause. Detailed recommendations on the classification of non-cardiovascular causes of death are beyond the scope of this document. The level of detail required and the optimum classification will depend on the nature of the study population and the anticipated number and type of non-cardiovascular deaths. Any specific anticipated safety concern should be included as a separate cause of death. The following is a suggested list of non-cardiovascular* causes of death:

Non-Malignant Causes

- Pulmonary

- Renal

- Gastrointestinal

- Hepatobiliary

- Pancreatic

- Infection (includes sepsis)

- Non-infectious (e.g., systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS))

- Hemorrhage, not intracranial

- Non-cardiovascular system organ failure (e.g., hepatic failure)

- Non-cardiovascular surgery

- Other non-cardiovascular, specify: ________________

- Accidental/Trauma

- Suicide

- Drug Overdose

- Death due to a gastrointestinal bleed should not be considered a cardiovascular death.

Malignant Causes

Malignancy should be coded as the cause of death if:

- Death results directly from the cancer; or

- Death results from a complication of the cancer (e.g. infection, complication of surgery / chemotherapy / radiotherapy); or

- Death results from withdrawal of other therapies because of concerns relating to the poor prognosis associated with the cancer

Cancer deaths may arise from cancers that were present prior to randomization or which developed subsequently. It may be helpful to distinguish these two scenarios (i.e. worsening of prior malignancy; new malignancy). Suggested categorization includes common organ systems, hematologic, or unknown.

Definition of Undetermined Cause of Death

Undetermined Cause of Death refers to a death not attributable to one of the above categories of cardiovascular death or to a non-cardiovascular cause. Inability to classify the cause of death may be due to lack of information (e.g., the only available information is “patient died”) or when there is insufficient supporting information or detail to assign the cause of death. In general, the use of this category of death should be discouraged and should apply to a minimal number of patients in well-run clinical trials. A common analytic approach for cause of death analyses is to assume that all undetermined cases are included in the cardiovascular category (e.g., presumed cardiovascular death, specifically “death due to other cardiovascular causes”). Nevertheless, the appropriate classification and analysis of undetermined causes of death depends on the population, the intervention under investigation, and the disease process. The approach should be prespecified and described in the protocol and other trial documentation such as the endpoint adjudication procedures and/or the statistical analysis plan.

References

- ↑ Myerburg, Robert J. "Cardiac Arrest and Sudden Cardiac Death" in Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 7th edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005.

- ↑ Sudden Unexpected Death: Causes and Contributing Factors on poptop.hypermart.net.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 16th Edition, The McGraw-Hill Companies, ISBN 0-07-140235-7

- ↑ Safar P (1986). "Cerebral resuscitation after cardiac arrest: a review". Circulation. 74 (6 Pt 2): IV138–53. PMID 3536160. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Irwin and Rippe's Intensive Care Medicine by Irwin and Rippe, Fifth Edition (2003), Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, ISBN 0-7817-3548-3

- ↑ FDA guinace issued October 20, 2010