Sudden cardiac death definitions and diagnosis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

{{Sudden cardiac death}} | {{Sudden cardiac death}} | ||

{{CMG}} {{AE}} {{Sara.Zand}} | |||

{{CMG}} | ===Overview=== | ||

==Definitions and Diagnosis== | ==Definitions and Diagnosis== | ||

Revision as of 08:34, 30 January 2021

|

Sudden cardiac death Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Sudden cardiac death definitions and diagnosis On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Sudden cardiac death definitions and diagnosis |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Sudden cardiac death definitions and diagnosis |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Sara Zand, M.D.[2]

Overview

Definitions and Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of sudden cardiac arrest is made when the following diagnostic criteria are met:

- Absence of a palpable pulse of the heart[1]

- Absent carotid pulse

- Gasping respiration or NO respiration

- Loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion

References

- ↑ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 16th Edition, The McGraw-Hill Companies, ISBN 0-07-140235-7

- ↑ Zimetbaum, Peter; Josephson, Mark E. (1998). "Evaluation of Patients with Palpitations". New England Journal of Medicine. 338 (19): 1369–1373. doi:10.1056/NEJM199805073381907. ISSN 0028-4793.

- ↑ Noda, Takashi; Shimizu, Wataru; Taguchi, Atsushi; Aiba, Takeshi; Satomi, Kazuhiro; Suyama, Kazuhiro; Kurita, Takashi; Aihara, Naohiko; Kamakura, Shiro (2005). "Malignant Entity of Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation and Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Initiated by Premature Extrasystoles Originating From the Right Ventricular Outflow Tract". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 46 (7): 1288–1294. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.077. ISSN 0735-1097.

Cardiac Arrest is an abrupt cessation of pump function (evidenced by absence of a palpable pulse) of the heart that with prompt intervention could be reversed, but without it will lead to death.[1]

Due to inadequate cerebral perfusion, the patient will be unconscious and will have stopped breathing. The main diagnostic criterion to diagnose a cardiac arrest (as opposed to respiratory arrest, which shares many of the same features) is lack of circulation, however there are a number of ways of determining this.

In many cases, lack of carotid pulse is the gold standard for diagnosing cardiac arrest, but lack of a pulse (particularly in the peripheral pulses) may be a result of other conditions (e.g. shock), or simply an error on the part of the rescuer. Studies have shown that rescuers often make a mistake when checking the carotid pulse in an emergency, whether they are healthcare professionals[2][3] or lay persons.[4]

Owing to the inaccuracy in this method of diagnosis, some bodies such as the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) have de-emphasised its importance. The Resuscitation Council (UK), in line with the ERC's recommendations and those of the American Heart Association,[5] have suggested that the technique should be used only by healthcare professionals with specific training and expertise, and even then that it should be viewed in conjunction with other indicators such as agonal respiration.[6]

Various other methods for detecting circulation have been proposed. Guidelines following the 2000 International Liaison Committee on Resusciation (ILCOR) recommendations were for rescuers to look for "signs of circulation", but not specifically the pulse [5]. These signs included coughing, gasping, colour, twitching and movement.[7] However, in face of evidence that these guidelines were ineffective, the current recommendation of ILCOR is that cardiac arrest should be diagnosed in all casualties who are unconscious and not breathing normally.[5]

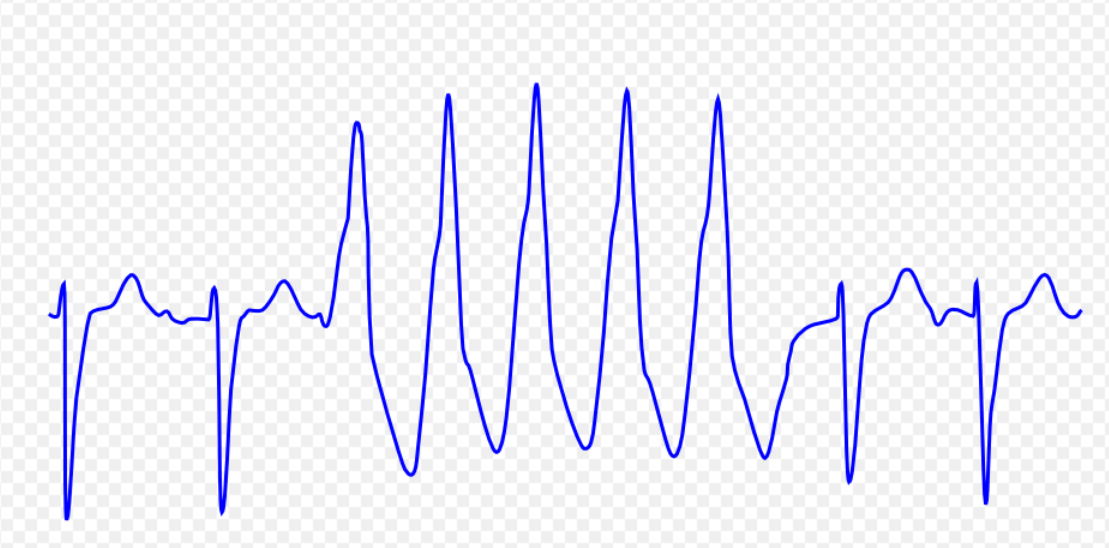

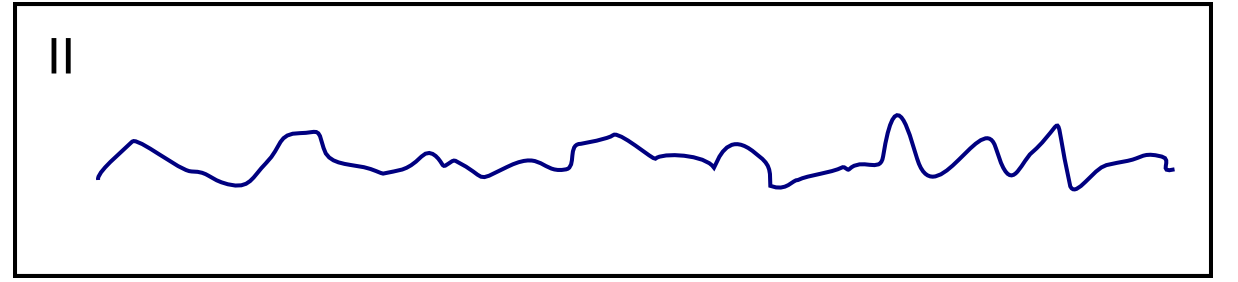

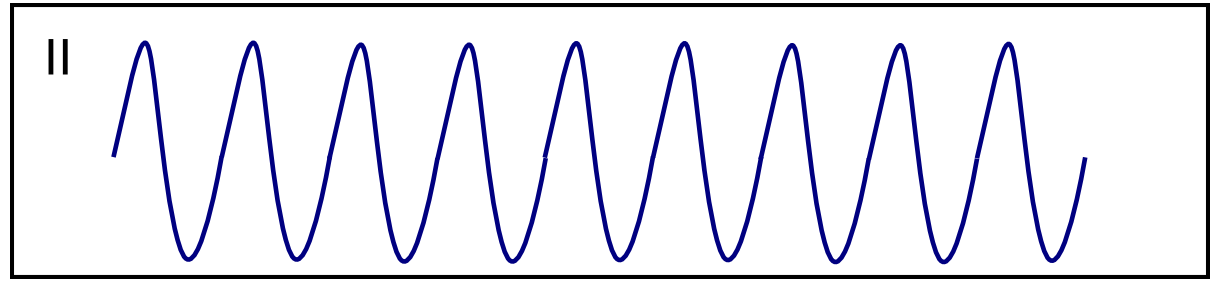

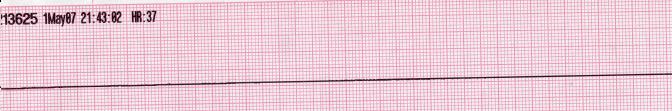

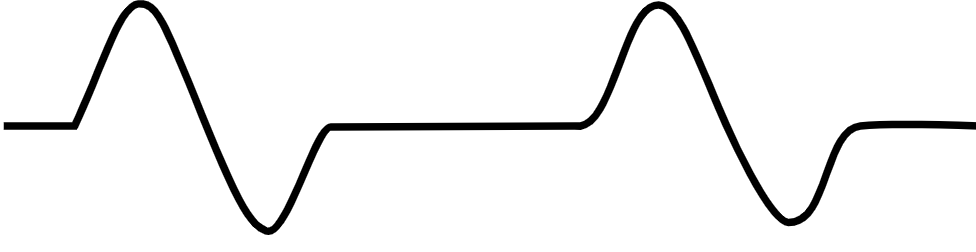

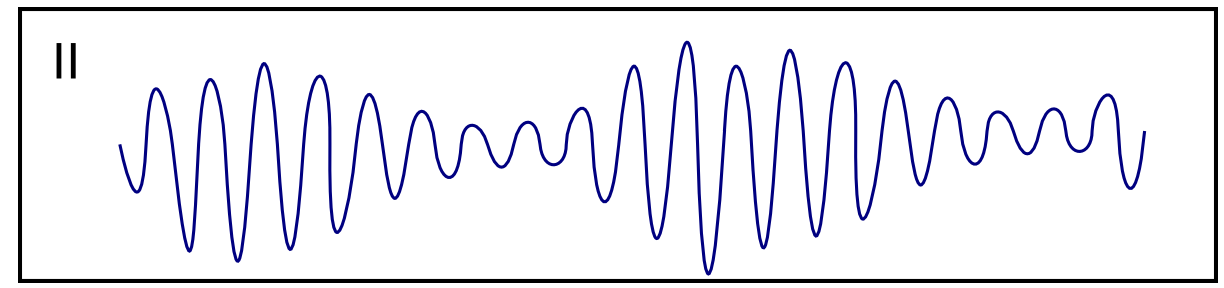

Following initial diagnosis of cardiac arrest, healthcare professionals further categorise the diagnosis based on the ECG/EKG rhythm. There are 4 rhythms which result in a cardiac arrest. Ventricular fibrillation (VF/VFib) and Pulseless Ventricular tachycardia (VT) are both responsive to a defibrillator and so are colloquially referred to as "Shockable" rhythms, whereas Asystole and Pulseless Electrical Activity (PEA) are non-shockable. The nature of the presenting hearth rhythm suggests different causes and treatment, and is used to guide the rescuer as to what treatment may be appropriate[6] (see Advanced Life Support and Advanced Cardiac Life Support, as well as the causes of arrest (below))

- The table below provides information on the differential diagnosis of sudden cardiac death in terms of ECG appearance:

| Disease Name | Causes | ECG Characteristics | ECG view |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventricular tachycardia [8][9][10][11][12] |

|

| |

| Ventricular fibrillation [14][15][16][17] |

|

| |

| Ventricular flutter [19][20][21] |

|

| |

| Asystole [23][24] |

|

| |

| Pulseless electrical activity [26][27] |

|

|

|

| Torsade de Pointes [29][30][31] |

|

|

References

- ↑ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 16th Edition, The McGraw-Hill Companies, ISBN 0-07-140235-7

- ↑ Flesche CW, Breuer S, Mandel LP, Breivik H, Tarnow J. (1994) The ability of health professionals to check the carotid pulse. Circulation Vol. 90: I–288.

- ↑ Ochoa FJ, Ramalle-Gómara E, Carpintero JM, García A, Saralegui I (1998). "Competence of health professionals to check the carotid pulse". Resuscitation. 37 (3): 173–5. PMID 9715777. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Bahr J, Klingler H, Panzer W, Rode H, Kettler D (1997). "Skills of lay people in checking the carotid pulse". Resuscitation. 35 (1): 23–6. PMID 9259056. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 112 (24 Suppl): IV1–203. 2005. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166550. PMID 16314375. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Resuscitation Council UK (2005). Resuscitation Guidelines 2005 London: Resuscitation Council UK.

- ↑ St John Ambulance, St Andrew's Ambulance Association, British Red Cross (2002) (8th Ed.) First Aid Manual. London: Dorling Kindersley

- ↑ Ajijola, Olujimi A.; Tung, Roderick; Shivkumar, Kalyanam (2014). "Ventricular tachycardia in ischemic heart disease substrates". Indian Heart Journal. 66: S24–S34. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2013.12.039. ISSN 0019-4832.

- ↑ Meja Lopez, Eliany; Malhotra, Rohit (2019). "Ventricular Tachycardia in Structural Heart Disease". Journal of Innovations in Cardiac Rhythm Management. 10 (8): 3762–3773. doi:10.19102/icrm.2019.100801. ISSN 2156-3977.

- ↑ Coughtrie, Abigail L; Behr, Elijah R; Layton, Deborah; Marshall, Vanessa; Camm, A John; Shakir, Saad A W (2017). "Drugs and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia risk: results from the DARE study cohort". BMJ Open. 7 (10): e016627. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016627. ISSN 2044-6055.

- ↑ El-Sherif, Nabil (2001). "Mechanism of Ventricular Arrhythmias in the Long QT Syndrome: On Hermeneutics". Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 12 (8): 973–976. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00973.x. ISSN 1045-3873.

- ↑ de Riva, Marta; Watanabe, Masaya; Zeppenfeld, Katja (2015). "Twelve-Lead ECG of Ventricular Tachycardia in Structural Heart Disease". Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 8 (4): 951–962. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002847. ISSN 1941-3149.

- ↑ ECG found in of https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ Koplan BA, Stevenson WG (March 2009). "Ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death". Mayo Clin. Proc. 84 (3): 289–97. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61149-X. PMC 2664600. PMID 19252119.

- ↑ Maury P, Sacher F, Rollin A, Mondoly P, Duparc A, Zeppenfeld K, Hascoet S (May 2017). "Ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in tetralogy of Fallot". Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 110 (5): 354–362. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2016.12.006. PMID 28222965.

- ↑ Saumarez RC, Camm AJ, Panagos A, Gill JS, Stewart JT, de Belder MA, Simpson IA, McKenna WJ (August 1992). "Ventricular fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is associated with increased fractionation of paced right ventricular electrograms". Circulation. 86 (2): 467–74. doi:10.1161/01.cir.86.2.467. PMID 1638716.

- ↑ Bektas, Firat; Soyuncu, Secgin (2012). "Hypokalemia-induced Ventricular Fibrillation". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 42 (2): 184–185. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.079. ISSN 0736-4679.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ Thies, Karl-Christian; Boos, Karin; Müller-Deile, Kai; Ohrdorf, Wolfgang; Beushausen, Thomas; Townsend, Peter (2000). "Ventricular flutter in a neonate—severe electrolyte imbalance caused by urinary tract infection in the presence of urinary tract malformation". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 18 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(99)00161-4. ISSN 0736-4679.

- ↑ Koster, Rudolph W.; Wellens, Hein J.J. (1976). "Quinidine-induced ventricular flutter and fibrillation without digitalis therapy". The American Journal of Cardiology. 38 (4): 519–523. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(76)90471-9. ISSN 0002-9149.

- ↑ Dhurandhar RW, Nademanee K, Goldman AM (1978). "Ventricular tachycardia-flutter associated with disopyramide therapy: a report of three cases". Heart Lung. 7 (5): 783–7. PMID 250503.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ ACLS: Principles and Practice. p. 71-87. Dallas: American Heart Association, 2003. ISBN 0-87493-341-2.

- ↑ ACLS for Experienced Providers. p. 3-5. Dallas: American Heart Association, 2003. ISBN 0-87493-424-9.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- ↑ "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care - Part 7.2: Management of Cardiac Arrest." Circulation 2005; 112: IV-58 - IV-66.

- ↑ Foster B, Twelve Lead Electrocardiography, 2nd edition, 2007

- ↑ ECG found in wikimedia Commons

- ↑ Li M, Ramos LG (July 2017). "Drug-Induced QT Prolongation And Torsades de Pointes". P T. 42 (7): 473–477. PMC 5481298. PMID 28674475.

- ↑ Sharain, Korosh; May, Adam M.; Gersh, Bernard J. (2015). "Chronic Alcoholism and the Danger of Profound Hypomagnesemia". The American Journal of Medicine. 128 (12): e17–e18. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.051. ISSN 0002-9343.

- ↑ Khan IA (2001). "Twelve-lead electrocardiogram of torsades de pointes". Tex Heart Inst J. 28 (1): 69. PMC 101137. PMID 11330748.

- ↑ ECG found in https://en.ecgpedia.org/index.php?title=Main_Page