Langerhans cell histiocytosis differential diagnosis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Ahmed Younes (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 289: | Line 289: | ||

|} | |} | ||

Langerhans cell histiocytosis must be differentiated from other diseases that cause [[bone pain]], [[edema]], and [[erythema]]. | |||

{| style="border: 0px; font-size: 90%; margin: 3px;" align=center | |||

|+ | |||

! style="background: #4479BA; width: 180px;" | {{fontcolor|#ffffff|Disease}} | |||

! style="background: #4479BA; width: 650px;" | {{fontcolor|#ffffff|Findings}} | |||

|- | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #DCDCDC;" | '''Soft tissue infection'''<br> (Commonly [[cellulitis]]) | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #F5F5F5;" | History of skin warmness, swelling and erythema. Bone probing is the definite way to differentiate them.<ref name="pmid8532002">{{cite journal |vauthors=Bisno AL, Stevens DL |title=Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=334 |issue=4 |pages=240–5 |year=1996 |pmid=8532002 |doi=10.1056/NEJM199601253340407 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid24947530">{{cite journal |vauthors=Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJ, Gorbach SL, Hirschmann JV, Kaplan SL, Montoya JG, Wade JC |title=Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases society of America |journal=Clin. Infect. Dis. |volume=59 |issue=2 |pages=147–59 |year=2014 |pmid=24947530 |doi=10.1093/cid/ciu296 |url=}}</ref> | |||

|- | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #DCDCDC;" |'''[[Osteonecrosis]]'''<br>(Avascular necrosis of bone) | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #F5F5F5;" |Previous history of trauma, radiation, use of steroids or biphosphonates are suggestive to differentiate osteonecrosis from ostemyelitis.<ref name="pmid21865285">{{cite journal |vauthors=Shigemura T, Nakamura J, Kishida S, Harada Y, Ohtori S, Kamikawa K, Ochiai N, Takahashi K |title=Incidence of osteonecrosis associated with corticosteroid therapy among different underlying diseases: prospective MRI study |journal=Rheumatology (Oxford) |volume=50 |issue=11 |pages=2023–8 |year=2011 |pmid=21865285 |doi=10.1093/rheumatology/ker277 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid25480307">{{cite journal |vauthors=Slobogean GP, Sprague SA, Scott T, Bhandari M |title=Complications following young femoral neck fractures |journal=Injury |volume=46 |issue=3 |pages=484–91 |year=2015 |pmid=25480307 |doi=10.1016/j.injury.2014.10.010 |url=}}</ref><br> MRI is diagnostic.<ref name="pmid22022684">{{cite journal |vauthors=Amanatullah DF, Strauss EJ, Di Cesare PE |title=Current management options for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: part 1, diagnosis and nonoperative management |journal=Am J. Orthop. |volume=40 |issue=9 |pages=E186–92 |year=2011 |pmid=22022684 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid15116601">{{cite journal |vauthors=Etienne G, Mont MA, Ragland PS |title=The diagnosis and treatment of nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head |journal=Instr Course Lect |volume=53 |issue= |pages=67–85 |year=2004 |pmid=15116601 |doi= |url=}}</ref> | |||

|- | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #DCDCDC;" |'''[[Charcot arthropathy|Charcot joint]]''' | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #F5F5F5;" |Patients with [[Charcot arthropathy|Charcot joint]] commonly develop skin ulcerations that can in turn lead to secondary osteomyelitis.<br>Contrast-enhanced MRI may be diagnostically useful if it shows a sinus tract, replacement of soft tissue fat, a fluid collection, or extensive marrow abnormalities. Bone biopsy is the definitive diagnostic modality.<ref name="pmid16436821">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ahmadi ME, Morrison WB, Carrino JA, Schweitzer ME, Raikin SM, Ledermann HP |title=Neuropathic arthropathy of the foot with and without superimposed osteomyelitis: MR imaging characteristics |journal=Radiology |volume=238 |issue=2 |pages=622–31 |year=2006 |pmid=16436821 |doi=10.1148/radiol.2382041393 |url=}}</ref> | |||

|- | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #DCDCDC;" |'''[[Bone tumors]]''' | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #F5F5F5;" |May present with local pain and radiographic changes consistent with osteomyelitis. <br>Tumors most likely to mimic osteomyelitis are ''osteoid osteomas'' and ''chondroblastomas'' that produce small, round, radiolucent lesions on radiographs.<ref>{{cite book | last = Lovell | first = Wood | title = Lovell and Winter's pediatric orthopaedics | publisher = Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins | location = Philadelphia | year = 2014 | isbn = 978-1605478142 }}</ref> | |||

|- | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #DCDCDC;" |'''[[Gout]]''' | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #F5F5F5;" |Gout presents with [[joint pain]] and [[swelling]]. Joint aspiration and crystals in synovial fluid is diagnostic for gout.<ref name="pmid20662061">{{cite journal |vauthors=Joosten LA, Netea MG, Mylona E, Koenders MI, Malireddi RK, Oosting M, Stienstra R, van de Veerdonk FL, Stalenhoef AF, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Kanneganti TD, van der Meer JW |title=Engagement of fatty acids with Toll-like receptor 2 drives interleukin-1β production via the ASC/caspase 1 pathway in monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced gouty arthritis |journal=Arthritis Rheum. |volume=62 |issue=11 |pages=3237–48 |year=2010 |pmid=20662061 |pmc=2970687 |doi=10.1002/art.27667 |url=}}</ref> | |||

|- | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #DCDCDC;" |'''[[SAPHO syndrome]]'''<br>(Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #F5F5F5;" |[[SAPHO syndrome]] consists of a wide spectrum of neutrophilic [[dermatosis]] associated with aseptic osteoarticular lesions. <br>It can mimic osteomyelitis in patients who lack the characteristic findings of pustulosis and [[synovitis]]. <br>The diagnosis is established via clinical manifestations; bone culture is sterile in the setting of [[osteitis]]. | |||

|- | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #DCDCDC;" |'''[[Sarcoidosis]]''' | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #F5F5F5;" |It involves most frequently the pulmonary [[parenchyma]] and mediastinal lymph nodes, but any organ system can be affected. <br>Bone involvement is often bilateral and bones commonly affected include the middle and distal phalanges (producing “sausage finger”), wrist, skull, vertebral column, and long bones. | |||

|- | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #DCDCDC;" |'''[[Langerhans' cell histiocytosis]]''' | |||

| style="padding: 7px 7px; background: #F5F5F5;" |The disease usually manifests in the skeleton and solitary bone lesions are encountered twice as often as multiple bone lesions.<br>The tumours can develop in any bone, but most commonly originate in the skull and jaw, followed by vertebral bodies, ribs, pelvis, and long bones.<ref name="pmid26461144">{{cite journal |vauthors=Picarsic J, Jaffe R |title=Nosology and Pathology of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis |journal=Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. |volume=29 |issue=5 |pages=799–823 |year=2015 |pmid=26461144 |doi=10.1016/j.hoc.2015.06.001 |url=}}</ref> | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{Reflist|2}} | {{Reflist|2}} | ||

Revision as of 05:48, 17 September 2017

|

Langerhans cell histiocytosis Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Langerhans cell histiocytosis from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Langerhans cell histiocytosis differential diagnosis On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Langerhans cell histiocytosis differential diagnosis |

|

Langerhans cell histiocytosis differential diagnosis in the news |

|

Blogs on Langerhans cell histiocytosis differential diagnosis |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Langerhans cell histiocytosis differential diagnosis |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Haytham Allaham, M.D. [2]

Overview

Langerhans cell histiocytosis must be differentiated from other diseases that cause bone pain, cutaneous lesions, hepatosplenomegaly, and palpable lymph nodes, such as cat-scratch disease, mastocytosis, sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy.[1][2]

Differentiating Langerhans cell histiocytosis from other Diseases

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis must be differentiated from other diseases that cause bone pain, cutaneous lesions, hepatosplenomegaly, and palpable lymph nodes, such as:[1][2]

- Lymphoma

- Mastocytosis

- Cat-scratch disease

- Hypersensitivity reaction

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica

- Erdheim-Chester disease

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy

- Kimura disease

- Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis

- Erythema toxicum neonatorum

- Acropustulosis of infancy

| Disease | Rash Characteristics | Signs and Symptoms | Associated Conditions | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|

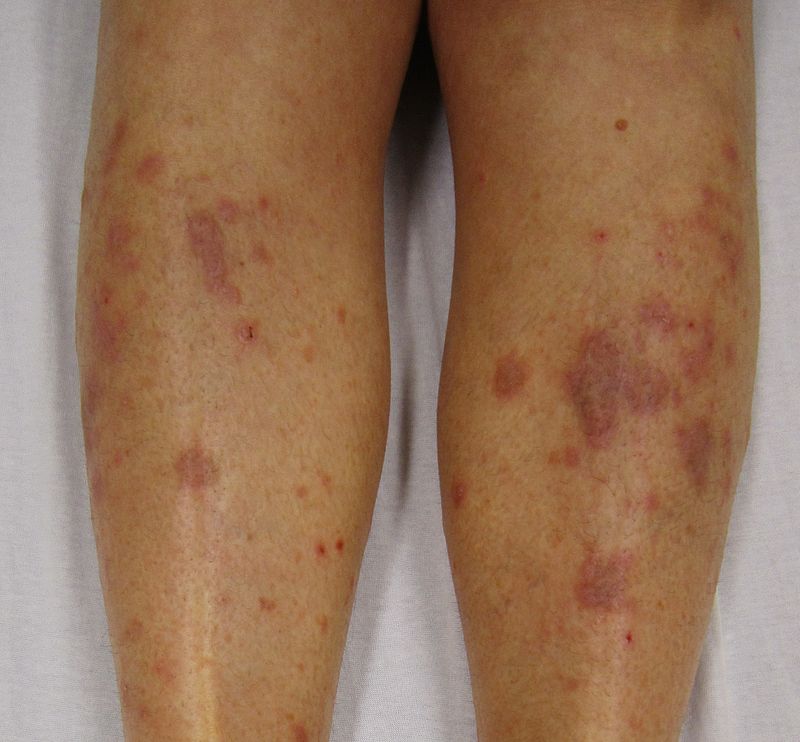

| Cutaneous T cell lymphoma/Mycosis fungoides[3] |

|

|

||

| Pityriasis rosea[4] |

|

|

||

| Pityriasis lichenoides chronica |

|

|

||

| Nummular dermatitis[7] |

|

|

|

|

| Secondary syphilis[8] |

|

|||

| Bowen’s disease[9] |

|

|

||

| Exanthematous pustulosis[11] |

|

|

||

| Hypertrophic lichen planus[13] |

|

|

|

|

| Sneddon–Wilkinson disease[15] |

|

|

||

| Small plaque parapsoriasis[19] |

|

|

|

|

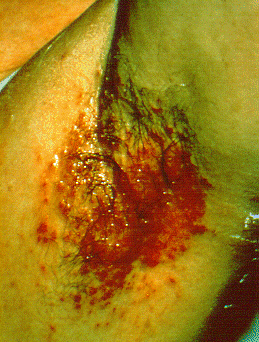

| Intertrigo[21] |

|

|

||

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis[22] |

|

|

|

|

| Tinea manuum/pedum/capitis[26] |

|

|

|

|

| Seborrheic dermatitis |

|

|

Langerhans cell histiocytosis must be differentiated from other diseases that cause bone pain, edema, and erythema.

| Disease | Findings |

|---|---|

| Soft tissue infection (Commonly cellulitis) |

History of skin warmness, swelling and erythema. Bone probing is the definite way to differentiate them.[29][30] |

| Osteonecrosis (Avascular necrosis of bone) |

Previous history of trauma, radiation, use of steroids or biphosphonates are suggestive to differentiate osteonecrosis from ostemyelitis.[31][32] MRI is diagnostic.[33][34] |

| Charcot joint | Patients with Charcot joint commonly develop skin ulcerations that can in turn lead to secondary osteomyelitis. Contrast-enhanced MRI may be diagnostically useful if it shows a sinus tract, replacement of soft tissue fat, a fluid collection, or extensive marrow abnormalities. Bone biopsy is the definitive diagnostic modality.[35] |

| Bone tumors | May present with local pain and radiographic changes consistent with osteomyelitis. Tumors most likely to mimic osteomyelitis are osteoid osteomas and chondroblastomas that produce small, round, radiolucent lesions on radiographs.[36] |

| Gout | Gout presents with joint pain and swelling. Joint aspiration and crystals in synovial fluid is diagnostic for gout.[37] |

| SAPHO syndrome (Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) |

SAPHO syndrome consists of a wide spectrum of neutrophilic dermatosis associated with aseptic osteoarticular lesions. It can mimic osteomyelitis in patients who lack the characteristic findings of pustulosis and synovitis. The diagnosis is established via clinical manifestations; bone culture is sterile in the setting of osteitis. |

| Sarcoidosis | It involves most frequently the pulmonary parenchyma and mediastinal lymph nodes, but any organ system can be affected. Bone involvement is often bilateral and bones commonly affected include the middle and distal phalanges (producing “sausage finger”), wrist, skull, vertebral column, and long bones. |

| Langerhans' cell histiocytosis | The disease usually manifests in the skeleton and solitary bone lesions are encountered twice as often as multiple bone lesions. The tumours can develop in any bone, but most commonly originate in the skull and jaw, followed by vertebral bodies, ribs, pelvis, and long bones.[38] |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Langerhans cell histiocytosis. PathologyOutlines (2015) http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lymphnodesLCH.html Accessed on February, 4 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. National Organization for Rare Disoders (2015) http://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/langerhans-cell-histiocytosis/ Accessed on February, 4 2016

- ↑ "Mycosis Fungoides and the Sézary Syndrome Treatment (PDQ®)—Patient Version - National Cancer Institute".

- ↑ Mahajan K, Relhan V, Relhan AK, Garg VK (2016). "Pityriasis Rosea: An Update on Etiopathogenesis and Management of Difficult Aspects". Indian J Dermatol. 61 (4): 375–84. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.185699. PMC 4966395. PMID 27512182.

- ↑ Prantsidis A, Rigopoulos D, Papatheodorou G, Menounos P, Gregoriou S, Alexiou-Mousatou I, Katsambas A (2009). "Detection of human herpesvirus 8 in the skin of patients with pityriasis rosea". Acta Derm. Venereol. 89 (6): 604–6. doi:10.2340/00015555-0703. PMID 19997691.

- ↑ Smith KJ, Nelson A, Skelton H, Yeager J, Wagner KF (1997). "Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta in HIV-1+ patients: a marker of early stage disease. The Military Medical Consortium for the Advancement of Retroviral Research (MMCARR)". Int. J. Dermatol. 36 (2): 104–9. PMID 9109005.

- ↑ Jiamton S, Tangjaturonrusamee C, Kulthanan K (2013). "Clinical features and aggravating factors in nummular eczema in Thais". Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 31 (1): 36–42. PMID 23517392.

- ↑ "STD Facts - Syphilis".

- ↑ Neagu TP, Ţigliş M, Botezatu D, Enache V, Cobilinschi CO, Vâlcea-Precup MS, GrinŢescu IM (2017). "Clinical, histological and therapeutic features of Bowen's disease". Rom J Morphol Embryol. 58 (1): 33–40. PMID 28523295.

- ↑ Murao K, Yoshioka R, Kubo Y (2014). "Human papillomavirus infection in Bowen disease: negative p53 expression, not p16(INK4a) overexpression, is correlated with human papillomavirus-associated Bowen disease". J. Dermatol. 41 (10): 878–84. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12613. PMID 25201325.

- ↑ Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA (2015). "Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): A review and update". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 73 (5): 843–8. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017. PMID 26354880.

- ↑ Schmid S, Kuechler PC, Britschgi M, Steiner UC, Yawalkar N, Limat A, Baltensperger K, Braathen L, Pichler WJ (2002). "Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: role of cytotoxic T cells in pustule formation". Am. J. Pathol. 161 (6): 2079–86. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64486-0. PMC 1850901. PMID 12466124.

- ↑ Ankad BS, Beergouder SL (2016). "Hypertrophic lichen planus versus prurigo nodularis: a dermoscopic perspective". Dermatol Pract Concept. 6 (2): 9–15. doi:10.5826/dpc.0602a03. PMC 4866621. PMID 27222766.

- ↑ Shengyuan L, Songpo Y, Wen W, Wenjing T, Haitao Z, Binyou W (2009). "Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus: a reciprocal association determined by a meta-analysis". Arch Dermatol. 145 (9): 1040–7. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.200. PMID 19770446.

- ↑ Lutz ME, Daoud MS, McEvoy MT, Gibson LE (1998). "Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: a clinical study of ten patients". Cutis. 61 (4): 203–8. PMID 9564592.

- ↑ Kasha EE, Epinette WW (1988). "Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) in association with a monoclonal IgA gammopathy: a report and review of the literature". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 19 (5 Pt 1): 854–8. PMID 3056995.

- ↑ Delaporte E, Colombel JF, Nguyen-Mailfer C, Piette F, Cortot A, Bergoend H (1992). "Subcorneal pustular dermatosis in a patient with Crohn's disease". Acta Derm. Venereol. 72 (4): 301–2. PMID 1357895.

- ↑ Sauder MB, Glassman SJ (2013). "Palmoplantar subcorneal pustular dermatosis following adalimumab therapy for rheumatoid arthritis". Int. J. Dermatol. 52 (5): 624–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05707.x. PMID 23489057.

- ↑ Lambert WC, Everett MA (1981). "The nosology of parapsoriasis". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 5 (4): 373–95. PMID 7026622.

- ↑ Väkevä L, Sarna S, Vaalasti A, Pukkala E, Kariniemi AL, Ranki A (2005). "A retrospective study of the probability of the evolution of parapsoriasis en plaques into mycosis fungoides". Acta Derm. Venereol. 85 (4): 318–23. doi:10.1080/00015550510030087. PMID 16191852.

- ↑ Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, Szepietowski JC, Reich A (2005). "Intertrigo and common secondary skin infections". Am Fam Physician. 72 (5): 833–8. PMID 16156342.

- ↑ Satter EK, High WA (2008). "Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society". Pediatr Dermatol. 25 (3): 291–5. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00669.x. PMID 18577030.

- ↑ Stull MA, Kransdorf MJ, Devaney KO (1992). "Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone". Radiographics. 12 (4): 801–23. doi:10.1148/radiographics.12.4.1636041. PMID 1636041.

- ↑ Sholl LM, Hornick JL, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Padera RF (2007). "Immunohistochemical analysis of langerin in langerhans cell histiocytosis and pulmonary inflammatory and infectious diseases". Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 31 (6): 947–52. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000249443.82971.bb. PMID 17527085.

- ↑ Grois N, Pötschger U, Prosch H, Minkov M, Arico M, Braier J, Henter JI, Janka-Schaub G, Ladisch S, Ritter J, Steiner M, Unger E, Gadner H (2006). "Risk factors for diabetes insipidus in langerhans cell histiocytosis". Pediatr Blood Cancer. 46 (2): 228–33. doi:10.1002/pbc.20425. PMID 16047354.

- ↑ Al Hasan M, Fitzgerald SM, Saoudian M, Krishnaswamy G (2004). "Dermatology for the practicing allergist: Tinea pedis and its complications". Clin Mol Allergy. 2 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1476-7961-2-5. PMC 419368. PMID 15050029.

- ↑ Schwartz RA, Janusz CA, Janniger CK (2006). "Seborrheic dermatitis: an overview". Am Fam Physician. 74 (1): 125–30. PMID 16848386.

- ↑ Misery L, Touboul S, Vinçot C, Dutray S, Rolland-Jacob G, Consoli SG, Farcet Y, Feton-Danou N, Cardinaud F, Callot V, De La Chapelle C, Pomey-Rey D, Consoli SM (2007). "[Stress and seborrheic dermatitis]". Ann Dermatol Venereol (in French). 134 (11): 833–7. PMID 18033062.

- ↑ Bisno AL, Stevens DL (1996). "Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues". N. Engl. J. Med. 334 (4): 240–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM199601253340407. PMID 8532002.

- ↑ Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJ, Gorbach SL, Hirschmann JV, Kaplan SL, Montoya JG, Wade JC (2014). "Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases society of America". Clin. Infect. Dis. 59 (2): 147–59. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu296. PMID 24947530.

- ↑ Shigemura T, Nakamura J, Kishida S, Harada Y, Ohtori S, Kamikawa K, Ochiai N, Takahashi K (2011). "Incidence of osteonecrosis associated with corticosteroid therapy among different underlying diseases: prospective MRI study". Rheumatology (Oxford). 50 (11): 2023–8. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker277. PMID 21865285.

- ↑ Slobogean GP, Sprague SA, Scott T, Bhandari M (2015). "Complications following young femoral neck fractures". Injury. 46 (3): 484–91. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2014.10.010. PMID 25480307.

- ↑ Amanatullah DF, Strauss EJ, Di Cesare PE (2011). "Current management options for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: part 1, diagnosis and nonoperative management". Am J. Orthop. 40 (9): E186–92. PMID 22022684.

- ↑ Etienne G, Mont MA, Ragland PS (2004). "The diagnosis and treatment of nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head". Instr Course Lect. 53: 67–85. PMID 15116601.

- ↑ Ahmadi ME, Morrison WB, Carrino JA, Schweitzer ME, Raikin SM, Ledermann HP (2006). "Neuropathic arthropathy of the foot with and without superimposed osteomyelitis: MR imaging characteristics". Radiology. 238 (2): 622–31. doi:10.1148/radiol.2382041393. PMID 16436821.

- ↑ Lovell, Wood (2014). Lovell and Winter's pediatric orthopaedics. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1605478142.

- ↑ Joosten LA, Netea MG, Mylona E, Koenders MI, Malireddi RK, Oosting M, Stienstra R, van de Veerdonk FL, Stalenhoef AF, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Kanneganti TD, van der Meer JW (2010). "Engagement of fatty acids with Toll-like receptor 2 drives interleukin-1β production via the ASC/caspase 1 pathway in monosodium urate monohydrate crystal-induced gouty arthritis". Arthritis Rheum. 62 (11): 3237–48. doi:10.1002/art.27667. PMC 2970687. PMID 20662061.

- ↑ Picarsic J, Jaffe R (2015). "Nosology and Pathology of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis". Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 29 (5): 799–823. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2015.06.001. PMID 26461144.