Addison's disease: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

== Epidemiology and Demographics== | == Epidemiology and Demographics== | ||

==Normal Function of Adrenal Glands== | ==Normal Function of Adrenal Glands== | ||

Revision as of 02:49, 12 August 2012

| Addison's disease | |

| ICD-10 | E27.1-E27.2 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 255.4 |

| DiseasesDB | 222 |

| MedlinePlus | 000378 |

| MeSH | D000224 |

|

Addison's disease Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Addison's disease On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Addison's disease |

For patient information click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Synonyms and keywords: Autoimmune adrenalitis; Addison disease, autoimmune; primary adrenal insufficiency; chronic adrenocortical insufficiency; adrenocortical hypofunction; hypocortisolism; hypocorticism

Overview

Epidemiology and Demographics

Normal Function of Adrenal Glands

Cortisol

Cortisol is normally produced by the adrenal glands, located just above the kidneys. It belongs to a class of hormones called glucocorticoids, which affect almost every organ and tissue in the body. Scientists think that cortisol has possibly hundreds of effects in the body. Cortisol's most important job is to help the body respond to stress. Among its other vital tasks, cortisol

- Helps maintain blood pressure and cardiovascular function

- Helps slow the immune system's inflammatory response

- Helps balance the effects of insulin in breaking down sugar for energy

- Helps regulate the metabolism of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats

- Helps maintain proper arousal and sense of well-being

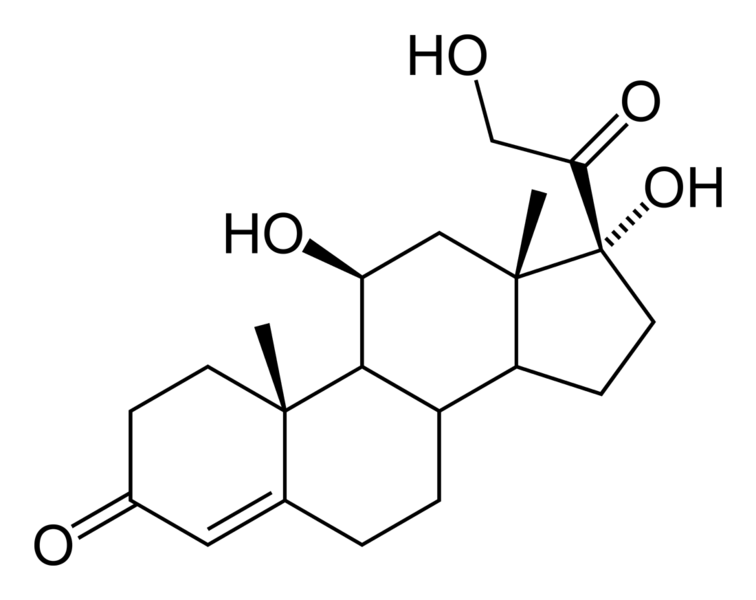

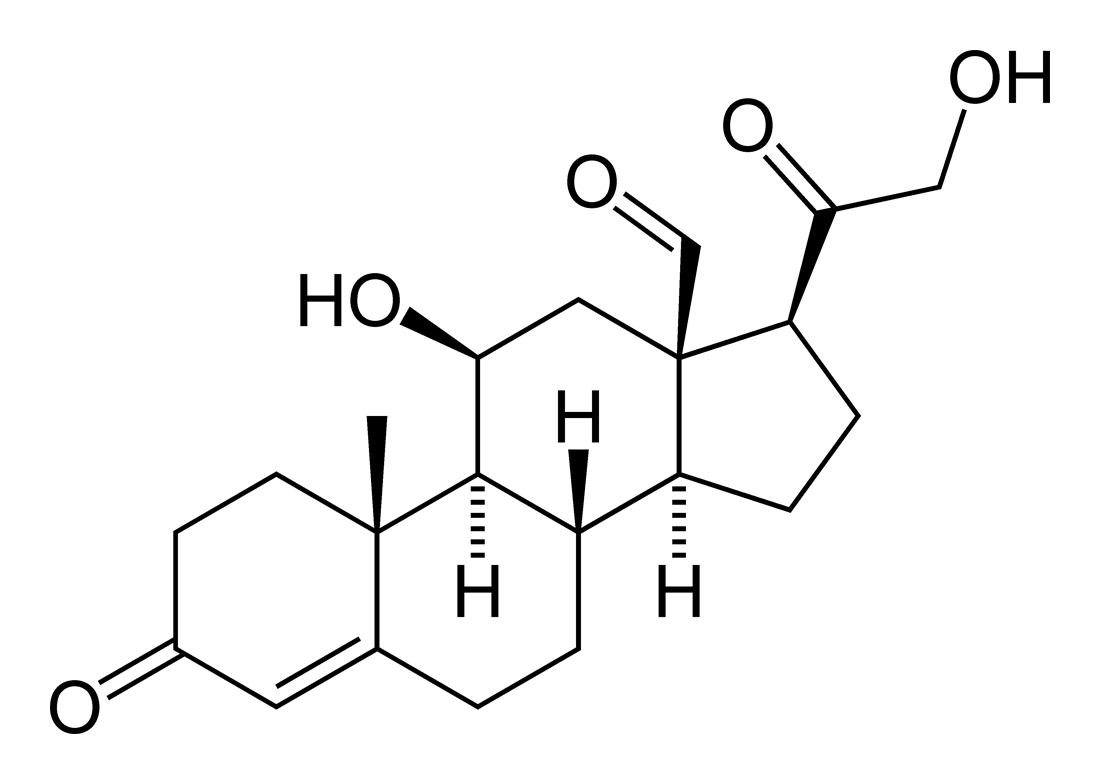

Because cortisol is so vital to health, the amount of cortisol produced by the adrenals is precisely balanced. Like many other hormones, cortisol is regulated by the brain's hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, a bean-sized organ at the base of the brain. First, the hypothalamus sends "releasing hormones" to the pituitary gland. The pituitary responds by secreting hormones that regulate growth and thyroid and adrenal function, and sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone. One of the pituitary's main functions is to secrete ACTH (adrenocorticotropin), a hormone that stimulates the adrenal glands. When the adrenals receive the pituitary's signal in the form of ACTH, they respond by producing cortisol. Completing the cycle, cortisol then signals the pituitary to lower secretion of ACTH.

Aldosterone

Aldosterone belongs to a class of hormones called mineralocorticoids, also produced by the adrenal glands. It helps maintain blood pressure and water and salt balance in the body by helping the kidney retain sodium and excrete potassium. When aldosterone production falls too low, the kidneys are not able to regulate salt and water balance, causing blood volume and blood pressure to drop.

Etiology and Pathophysiology of Addison's Disease

Addison's disease occurs when the adrenal glands do not produce enough of the hormone cortisol and, in some cases, the hormone aldosterone. The disease is also called adrenal insufficiency, or hypocortisolism. Causes of adrenal insufficiency can be grouped by the way in which they cause the adrenals to produce insufficient cortisol. These are adrenal dysgenesis (the gland has not formed adequately during development), impaired steroidogenesis (the gland is present but is biochemically unable to produce cortisol) or adrenal destruction (disease processes leading to the gland being damaged).[1]

Adrenal dysgenesis

All causes in this category are genetic, and generally very rare. These include mutations to the SF1 transcription factor, congenital adrenal hypoplasia (AHC) due to DAX-1 gene mutations and mutations to the ACTH receptor gene (or related genes, such as in the Triple A or Allgrove syndrome). DAX-1 mutations may cluster in a syndrome with glycerol kinase deficiency with a number of other symptoms when DAX-1 is deleted together with a number of other genes.[1]

Impaired steroidogenesis

To form cortisol, the adrenal gland requires cholesterol, which is then converted biochemically into steroid hormones. Interruptions in the delivery of cholesterol include Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome and abetalipoproteinemia. Of the synthesis problems, congenital adrenal hyperplasia is the most common (in various forms: 21-hydroxylase, 17α-hydroxylase, 11β-hydroxylase and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), lipod CAH due to deficiency of StAR and mitochondrial DNA mutations.[1]

Adrenal destruction

Autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex (often due to antibodies against the enzyme 21-Hydroxylase) is a common cause of Addison's in teenagers and adults. This may be isolated or in the context of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome (APS type 1 or 2). Adrenal destruction is also a feature of adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), and when the adrenal glands are involved in metastasis (seeding of cancer cells from elsewhere in the body), hemorrhage (e.g. in Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome or antiphospholipid syndrome), particular infections (tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis), deposition of abnormal protein in amyloidosis. Some medications interfere with steroid synthesis enzymes (e.g. ketoconazole), while others accelerate the normal breakdown of hormones by the liver (e.g. rifampicin, phenytoin).[1]

Complete differential diagnosis of causes of Addison's disease classified by Primary and Secondary causes [2]

Primary Adrenocoritcal Insufficiency (Addison's disease)

- Autoimmune/idiopathic

- Congenital

- Iatrogenic

- Radiation (therapy)

- Bilateral adrenalectomy

- Fungal

- Cryptococcosis

- Blastomycosis

- Syphilis

- Coccidiomycosis

- Tuberculosis (20% of all Addison's)

- Hemorrhage, infarction

- Trauma

- Surgery

- Sepsis

- Embolus

- Anticoagulation

- Arteritis

- Hypotension

- Neonatal

- Thrombosis

- Coagulopathy

- Infections

- Neoplasm

- Uremia

- Coma

- Infiltrative

- Volume / electrolyte disorders

- Drugs

Secondary (pituitary) or Tertiary (hypothalamic) Adrenocortical Insufficiency

- Drug withdrawal

- After surgery of cortisol-secreting tumor

Diagnosis

Symptoms

The symptoms of adrenal insufficiency develop insidiously, usually begin gradually and it may take some time to be recognized. Some have marked cravings for salty foods due to the urinary losses of sodium. Characteristics of the disease are [1]

- Chronic, worsening fatigue

- Muscle weakness

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Headache

- Sweating

- Changes in mood and personality

- muscle pains

- joint

About 50 percent of the time, one will notice:

Clinical signs

On examination, the following may be noticed:[1]

- Low blood pressure that falls further when standing (orthostatic hypotension)

- Darkening (hyperpigmentation) of the skin, including areas not exposed to the sun; characteristic sites are skin creases (e.g. of the hands), nipples, and the inside of the cheek (buccal mucosa), also old scars may darken.

- Signs of conditions that often occur together with Addison's: goiter and vitiligo

Because the symptoms progress slowly, they are usually ignored until a stressful event like an illness or an accident causes them to become worse. This is called an addisonian crisis, or acute adrenal insufficiency. In most cases, symptoms are severe enough that patients seek medical treatment before a crisis occurs. However, in about 25 percent of patients, symptoms first appear during an addisonian crisis.

Addisonian crisis

An "Addisonian crisis" or "adrenal crisis" is a constellation of symptoms that indicate severe adrenal insufficiency. This may be the result of either previously undiagnosed Addison's disease, a disease process suddenly affecting adrenal function (such as adrenal hemorrhage), or an intercurrent problem (e.g. infection, trauma) in the setting of known Addison's disease. Additionally, this situation may develop in those on long-term oral glucocorticoids who have suddenly ceased taking their medication. It is also a concern in the setting of myxedema coma; thyroxine given in that setting without glucocorticoids may precipitate a crisis.

Untreated, an Addisonian crisis can be fatal. It is a medical emergency, usually requiring hospitalization. Characteristic symptoms are:[3]

- Sudden penetrating pain in the legs, lower back or abdomen

- Severe vomiting and diarrhea, resulting in dehydration

- Low blood pressure

- Loss of consciousness/Syncope

- Hypoglycemia

- Confusion, psychosis

- Convulsions

Laboratory Findings

A diagnosis of Addison's disease is made by laboratory tests. The aim of these tests is first to determine whether levels of cortisol are insufficient and then to establish the cause. X-ray exams of the adrenal and pituitary glands also are useful in helping to establish the cause. In its early stages, adrenal insufficiency can be difficult to diagnose. A review of a patient's medical history based on the symptoms, especially the dark tanning of the skin, will lead a doctor to suspect Addison's disease.

In suspected cases of Addison's disease, one needs to demonstrate that adrenal hormone levels are low even after appropriate stimulation with synthetic pituitary hormone tetracosactide. Two tests are performed, the short and the long test.

The short test compares blood cortisol levels before and after 250 micrograms of tetracosactide (IM/IV) is given. If, one hour later, plasma cortisol exceeds 170 nmol/L and has risen by at least 330 nmol/L to at least 690 nmol/L, adrenal failure is excluded. If the short test is abnormal, the long test is used to differentiate between primary adrenal failure and secondary adrenocortical failure.

The long test uses 1 mg tetracosactide (IM). Blood is taken 1, 4, 8, and 24 hours later. Normal plasma cortisol level should reach 1000 nmol/L by 4 hours. In primary Addison's disease, the cortisol level is reduced at all stages whereas in secondary corticoadrenal insufficiency, a delayed but normal response is seen.

Other tests that may be performed to distinguish between various causes of hypoadrenalism are renin and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, as well as medical imaging - usually in the form of ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

ACTH Stimulation Test

This is the most specific test for diagnosing Addison's disease. In this test, blood cortisol, urine cortisol, or both are measured before and after a synthetic form of ACTH is given by injection. In the so-called short, or rapid, ACTH test, measurement of cortisol in blood is repeated 30 to 60 minutes after an intravenous ACTH injection. The normal response after an injection of ACTH is a rise in blood and urine cortisol levels. Patients with either form of adrenal insufficiency respond poorly or do not respond at all.

CRH Stimulation Test

When the response to the short ACTH test is abnormal, a "long" CRH stimulation test is required to determine the cause of adrenal insufficiency. In this test, synthetic CRH is injected intravenously and blood cortisol is measured before and 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after the injection. Patients with primary adrenal insufficiency have high ACTHs but do not produce cortisol. Patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency have deficient cortisol responses but absent or delayed ACTH responses. Absent ACTH response points to the pituitary as the cause; a delayed ACTH response points to the hypothalamus as the cause.

In patients suspected of having an addisonian crisis, the doctor must begin treatment with injections of salt, fluids, and glucocorticoid hormones immediately. Although a reliable diagnosis is not possible while the patient is being treated for the crisis, measurement of blood ACTH and cortisol during the crisis and before glucocorticoids are given is enough to make the diagnosis. Once the crisis is controlled and medication has been stopped, the doctor will delay further testing for up to 1 month to obtain an accurate diagnosis.

Suggestive features

Routine investigations may show:[1]

- Hypoglycemia, low blood sugar (worse in children)

- Hyponatraemia (low blood sodium levels)

- Hyperkalemia (raised blood potassium levels), due to loss of production of the hormone aldosterone

- Eosinophilia and lymphocytosis (increased number of eosinophils or lymphocytes, two types of white blood cells)

Treatment

Maintenance treatment

Treatment for Addison's disease involves replacing the missing cortisol (usually in the form of hydrocortisone tablets) in a dosing regimen that mimics the physiological concentrations of cortisol. Treatment must usually be continued for life. In addition, many patients require fludrocortisone as replacement for the missing aldosterone. Caution must be exercised when the person with Addison's disease becomes unwell, has surgery or becomes pregnant. Medication may need to be increased during times of stress, infection, or injury.

Addisonian crisis

Treatment for an acute attack, an Addisonian crisis, usually involves intravenous (into blood veins) injections of:

- Cortisone (cortisol)

- Saline solution (basically a salt water, same clear IV bag as used to treat dehydration)

- Glucose

Surgery

Surgeries may require significant adjustments to medication regimens prior to, during, and following any surgical procedure. The best preparation for any surgery, regardless of how minor or routine it may normally be, is to speak to one's primary physician about the procedure and medication implications well in advance of the surgery.

Pregnancy

Many women with Addison's have given birth successfully and without complication, both through natural labor and through cesarean delivery. Both of these methods will require different preventative measures relating to Addison's medications and dosages. As is always the case, thorough communication with one's primary physician is the best course of action. Occasionally, oral intake of medications will cause debilitating nausea and vomiting, and thus the woman may be switched to injected medications until delivery. [4] Addison's treatment courses by the mother are generally considered safe for baby during pregnancy.

Prognosis

While treatment solutions for Addison's disease are far from precise, overall long-term prognosis is typically good. Because of individual physiological differences, each person with Addison's must work closely with their physician to adjust their medication dosage and schedule to find the most effective routine. Once this is accomplished (and occasional adjustments must be made from time to time, especially during periods of travel, stress, or other medical conditions), symptomology is usually greatly reduced or occasionally eliminated so long as the person continues their dosage schedule.

Patient Education

A person who has adrenal insufficiency should always carry identification stating his or her condition in case of an emergency. The card should alert emergency personnel about the need to inject 100 mg of cortisol if its bearer is found severely injured or unable to answer questions. The card should also include the doctor's name and telephone number and the name and telephone number of the nearest relative to be notified. When traveling, a needle, syringe, and an injectable form of cortisol should be carried for emergencies. A person with Addison's disease also should know how to increase medication during periods of stress or mild upper respiratory infections. Immediate medical attention is needed when severe infections, vomiting, or diarrhea occur. These conditions can precipitate an addisonian crisis. A patient who is vomiting may require injections of hydrocortisone.

People with medical problems may wish to wear a descriptive warning bracelet or neck chain to alert emergency personnel. A number of companies manufacture medical identification products.

See also

References

Additional Resources

- Chrousos GP. Glucocorticoid therapy. In: Felig P, Frohman L, eds. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001: 609–632.

- Miller W, Chrousos GP. The adrenal cortex. In: Felig P, Frohman L, eds. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001: 387–524.

- Stewart PM. The adrenal cortex. In: Larsen P, ed. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003: 491–551.

- Ten S, New M, Maclaren N. Clinical Review 130: Addison's disease 2001. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2001;86(7):2909–2922.

External links

- Overview of Addison's Disease from the Mayo Clinic

- Addison's Disease Research Today - monthly online journal summarizing recent primary literature on Addison's disease

- National Adrenal Diseases Foundation

- Addison's information from MedicineNet

- "Addison's Disease: The Facts You Need to Know (MedHelp.org)

- The Addison & Cushing International Federation (ACIF)

- Addison's disease info from SeekWellness.com

- Information about Addison's disease in canines (dogs)

- Antibodies to adrenal gland

- Immunofluorescence images

- Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service

Support groups

- Addison's Disease Self Help Group (ADSHG) - UK support group

- Australian Addison's Disease Association - Australian support and information group

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Addison en Cushing Patiënten - Dutch support and information group with information and documentation in English

- Addresses of patient organisations and support groups around the world

bg:Адисонова болест cs:Addisonova choroba da:Addisons sygdom de:Nebennierenrindeninsuffizienz it:Morbo di Addison he:מחלת אדיסון ms:Penyakit Addison nl:Ziekte van Addison sk:Addisonova choroba fi:Addisonin tauti sv:Addisons sjukdom