Aortic dissection overview

|

Aortic dissection Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Special Scenarios |

|

Case Studies |

|

|

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Overview

Aortic dissection is a tear in the wall of the aorta that causes blood to flow between the layers of the wall of the aorta and force the layers apart. Aortic dissection is a medical emergency and can quickly lead to death, even with optimal treatment. If the dissection tears the aorta completely open (through all three layers) massive and rapid blood loss occurs. Aortic dissections resulting in rupture have a 90% mortality rate even if intervention is timely.

Acute aortic dissection is the most common fatal condition that involves the aorta. The mortality rate has been estimated to be as high as 1% per hour during the first 48 hours. Because of the diverse clinical manifestations of aortic dissection, one needs to maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with not just chest pain, but also those with stroke, congestive heart failure, hoarseness, hemoptysis, claudication, superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome, or upper airway obstruction. Despite the fact that a noninvasive diagnosis can be made in up to 90% of cases, the correct antemortem diagnosis is made less than 50% of the time. Recognition of the condition and vigorous pre-operative management are critical to survival.

Classification

Several different classification systems have been used to describe aortic dissections. The systems commonly in use are either based on either the anatomy of the dissection (proximal, distal) or the duration of onset of symptoms (acute, chronic) prior to presentation.

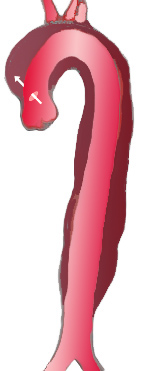

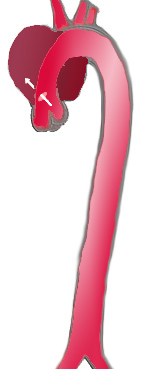

DeBakey Classification System

The DeBakey system is an anatomical description of the aortic dissection. It categorizes the dissection based on where the original intimal tear is located and the extent of the dissection (localized to either the ascending aorta or descending aorta, or involves both the ascending and descending aorta.[1]

- Type I - Originates in ascending aorta, propagates at least to the aortic arch and often beyond it distally.

- Type II – Originates in and is confined to the ascending aorta.

- Type III – Originates in descending aorta, rarely extends proximally.

|

|

| |

| Percentage | 60 % | 10-15 % | 25-30 % |

| Type | DeBakey I | DeBakey II | DeBakey III |

| Stanford A | Stanford B | ||

| Proximal | Distal | ||

| Classification of aortic dissection | |||

Stanford Classification System

Divided into 2 groups; A and B depending on whether the ascending aorta is involved.[2]

- A = Type I and II DeBakey

- B = Type III Debakey

Pathophysiology

Initial Intimal Tear

- Aortic dissection begins as a tear in the aortic wall in > 95% of patients.

- It is usually transverse, extends through the intima and halfway through the media and involves ~50% of the aortic circumference.

- Location of dissections:

- The initial tear is usually within 100 mm of the aortic valve.

- 65% of dissections originate in the ascending aorta, distal to the aortic valve and coronary ostia

- 10% arise in the transverse aortic arch

- 20% in the proximal descending aorta

- 5% in the more distal descending aorta

Propagation of the Intimal Tear

In an aortic dissection, blood penetrates the intima and enters the media layer. The high pressure rips the tissue of the media apart, allowing more blood to enter. This can propagate along the length of the aorta for a variable distance, dissecting either towards or away from the heart or both. Once a tear develops, blood then passes into the media, and a false lumen is dissected in the outer layer of aortic media involving ~50% of the aortic circumference. This false lumen can enlarge, and compress the true lumen, as well as extend proximally or distally and occlude aortic branches. For some unknown reason, the right lateral wall of the ascending aorta is the most common site for dissection. The right coronary artery can become occluded as a result of this propagation.

Separating the false lumen from the true lumen is a layer of intimal tissue. This tissue is known as the intimal flap. As blood flows down the false lumen, it may cause secondary tears in the intima. Through these secondary tears, the blood can re-enter the true lumen.

Causes

Age related changes due to atherosclerosis and hypertension are associated with spontaneous dissection, while blunt trauma injury and sudden deceleration in a motor vehicle accident is a major cause of aortic dissection.

Other risk factors and conditions associated with the development of aortic dissection include:

- Aging

- Bicuspid aortic valve

- Chest trauma

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Connective tissue disorders

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Heart surgery or procedures

- Marfan syndrome

- Third trimester of pregnancy

- Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

- Tertiary syphilis

- Turner's syndrome

- Vascular inflammation due to conditions such as arteritis and syphilis

Differentiating Aortic Dissection from other Diseases

Aortic dissection is a life threatening entity that must be distinguished from other life threatening entities such as cardiac tamponade, cardiogenic shock, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism. An aortic aneurysm is not synonymous with aortic dissection. Aneurysms are defined as a localized permanent dilation of the aorta to a diameter > 50% of normal. Other disorders that aortic dissection should be differentiated from include the following:

- Aortic Regurgitation

- Aortic Stenosis

- Cardiac Tamponade

- Cardiogenic Shock

- Gastroenteritis

- Hemorrhagic Shock

- Hernias

- Hypertensive Emergencies

- Hypovolemic Shock

- Mechanical Back Pain

- Myocardial Infarction

- Myocarditis

- Myopathies

- Pancreatitis

- Pericarditis

- Peripheral Vascular Injuries

- Pleural Effusion

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Epidemiology and Demographics

There are approximately 2,000 cases of aortic dissection in the US per year, and aortic dissection accounts for 3-4% of sudden deaths. The peak incidence is in the sixth and seventh decades, and males predominate 2:1.

Risk Factors

- Aging. The highest incidence of aortic dissection is in individuals who are 50 to 70 years old.

- Atherosclerosis and its associated risk factors like diabetes

- Bicuspid aortic valve is present in approximately 7%-14% of patients. These individuals are prone to dissection in the ascending aorta. The risk of dissection in individuals with bicuspid aortic valve is not associated with the degree of stenosis of the valve.

- Chest trauma. Chest trauma leading to aortic dissection can be divided into two groups based on etiology: blunt chest trauma (commonly seen in car accidents) and iatrogenic. Iatrogenic causes include trauma during cardiac catheterization or due to an intra-aortic balloon pump.

- Cocaine abuse

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Cystic medial necrosis

- Deceleration trauma most commonly causes aortic rupture, not dissection

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Giant cell arteritis

- Heart surgery particularly aortic valve replacement; 18% of individuals who present with an acute aortic dissection have a history of open heart surgery. Individuals who have undergone aortic valve replacement for aortic insufficiency are at particularly high risk. This is because aortic insufficiency causes increased blood flow in the ascending aorta. This can cause dilatation and weakening of the walls of the ascending aorta.

- Hypertension is seen in 71-86% of patients. It occurs most frequently in those with type III dissection.

- Male gender. The incidence is twice as high in males as in females (male-to-female ratio is 2:1).

- Marfan’s syndrome is present in 5%-9% of patients. In this subset, there is an increased incidence in young individuals. Individuals with Marfan syndrome patients are more prone to proximal dissections of the aorta.

- Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

- Turner's syndrome. Turner syndrome increases the risk of aortic dissection as a result of aortic root dilatation[3].

- Tertiary syphilis

- Third trimester of pregnancy. Half of dissections in females before age 40 occur during pregnancy (typically in the 3rd trimester or early postpartum period).

- Vasculitis (inflammation of an artery) is rarely associated with aortic dissection.

Natural History

If the patient remains untreated, the mortality is:

- 1% per hour during the first day

- 75% at 2 weeks

- 90% at 1 year

Complications

The complications of aortic dissection include:

Cardiac

- Aortic rupture leading to massive blood loss, hypotension and shock often resulting in death. Indeed, aortic dissection accounts for 3-4% of sudden deaths.

- Pericardial tamponade due to extension of the dissection into the pericardium

- Acute aortic regurgitationdue to the aortic dilation and dissection into the valve structure which can then cause acute pulmonary edema

- Myocardial ischemia or myocardial infarction due to dissection into either the right or left coronary ostium (but most commonly the right coronary artery)

- Redissection and aortic diameter enlargement

- Aneurysmal dilatation and saccular aneurysm chronically

Kidney

- Mesenteric and renal ischemia due to dissection into the ostium of the parent vessels which can lead to hematuria, renal infarction, acute renal failure, or visceral ischemia

Peripheral Arterial

- Claudication due to an extension of the dissection into the iliac arteries

Neurologic

- Ischemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA) due to dissection into the head vessels

- Hemiplegia due to dissection into the spinal arteries

- Hemianesthesia due to dissection into the spinal arteries

Compression of Nearby Organs

- Swelling of the neck and face (compression of the superior vena cava or Superior vena cava syndrome)

- Horner syndrome (compression of the superior cervical ganglia)

- Dysphagia (compression of the esophagus)

- Stridor and wheezing (compression of the airway)

- Hemoptysis (compression of and erosion into the bronchus)

- Vocal cord paralysis and hoarseness (compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve)

Prognosis

The mortality rate is in large part determined by the patient's age and comorbidities.

- 30% in hospital mortality

- 60% 10-year survival rate among treated patients

Type A aortic dissection

Type B aortic dissection

History and Symptoms

67% of patients with aortic dissection present with acute symptoms (<2 weeks), and 33% with chronic symptoms (>= 2 weeks). 74% of patients who survive the initial tear typically present with the sudden onset of severe tearing pain.

Pain

Chest Pain

92% of patients with anterior chest pain as their major source of pain have either type I or type II dissections, and only 8% have type III. In 17% patients, the pain migrates as dissection extends down the aorta.

Neck, Throat, and Jaw Pain

Neck, throat, jaw, and unilateral face pain are also seen more commonly in those with type I or type II dissection.

Back Pain

52% of patients with type III dissection have the majority of their pain in the back, and 67% of these patients have some degree of back pain.

Pleuritic Pain

Pleuritic pain suggests acute pericarditis associated with hemorrhage into the pericardial sac.

Painless Dissection

Up to 15 – 55 % of patients can have painless dissection. Dissection should therefore be included in the differential in patients with unexplained syncope, stroke or congestive heart failure (CHF).

Infrequent Symptoms

- Abdominal pain due to mesenteric ischemia

- Cardiac arrest occurs in 4% of patients

- Claudication due to iliac artery occlusion

- Congestive heart failure may be observed due to aortic root dilatation leading to aortic insufficiency

- Dysphagia due to compression of the esophagus

- Hemoptysis due to compression of and erosion into the bronchus

- Horner syndrome due to compression of the superior cervical ganglia

- Oliguria/ Anuria due to involvement of the renal arteries causing pre-renal azotemia.[4] [5] [6] [7]

- Paraplegia, paralysis from involvement of one of the cerebral or spinal arteries

- Stridor and wheezing due to compression of the airway

- Swelling of the neck and face due to compression of the superior vena cava or Superior vena cava syndrome

- Syncope may occur and in 50% of cases, the etiology of the syncope is hemorrhage into the pericardial sac causing pericardial tamponade

- Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleed

- Vocal cord paralysis and hoarseness (compression of the recurrent laryngeal nerve)

Physical Examination

Blood Pressure

Blood Pressure Discrepancy

Pseudohypotension (falsely low blood pressure measurement) may occur due to involvement of the brachiocephalic artery (supplying the right arm) or the left subclavian artery (supplying the left arm).

Hypertension

While many patients with an aortic dissection have a history of hypertension, the blood pressure is quite variable among patients with acute aortic dissection, and tends to be higher in individuals with a distal dissection. In individuals with a proximal aortic dissection, 36% present with hypertension, while 25% present with hypotension. In those that present with distal aortic dissections, 70% present with hypertension while 4% present with hypotension.

Hypotension

Severe hypotension at presentation is a grave prognostic indicator. It is usually associated with pericardial tamponade, severe aortic insufficiency, or rupture of the aorta. Accurate measurement of the blood pressure is important.

Pulse

- Tachycardia may be present due to pain, anxiety, aortic rupture with massive bleeding, pericardial tamponade, aortic insufficiency with acute pulmonary edema and hypoxemia.

- A wide pulse pressure may be present if acute aortic insufficiency develops.

- Pulsus paradoxus (a drop of > 10 mmHg in arterial blood pressure on inspiration) may be present of pericardial tamponade develops.

General

The patient may be hoarse due to compression of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve

Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat

- Swelling of the neck and face may be present due to compression of the superior vena cava or Superior vena cava syndrome

- Horner syndrome may be present due to compression of the superior cervical ganglia

Heart

Aortic Insufficiency

Aortic insufficiency occurs in 1/2 to 2/3 of ascending aortic dissections, and the murmur of aortic insufficiency is audible in about 32% of proximal dissections. The intensity (loudness) of the murmur is dependent on the blood pressure and may be inaudible in the event of hypotension. Aortic insufficiency is more commonly associated with type I or type II dissection. The murmur of aortic insufficiency (AI) due to aortic dissection is best heard at the right 2nd intercostal space (ICS), as compared with the lower left sternal border for AI due to primary aortic valvular disease.

Cardiac Tamponade

- Beck's triad may be present:[8]

- Hypotension (due to decreased stroke volume)

- Jugular venous distension (due to impaired venous return to the heart)

- Muffled heart sounds (due to fluid inside the pericardium) [9]

- Distension of veins in the forehead and scalp

- Altered sensorium (decreasing Glasgow coma scale)

- Peripheral edema

In addition to the Beck's triad and pulsus paradoxus the following can be found on cardiovascular examination:

- Pericardial rub

- Clicks - As ventricular volume shrinks disproportionately, there may be psuedoprolapse/true prolapse of mitral and/or tricuspid valvular structures that result in clicks.

- Kussmaul's sign - Decrease in jugular venous pressure with inspiration is uncommon.

Lungs

- Rales may be present due to cardiogenic pulmonary edema which may result from acute aortic regurgitation.

- Hemothorax and / or pleural effusion may cause dullness to percussion.

- Stridor and wheezing may be present due to compression of the airway

- Hemoptysis may be present due to compression of and erosion into the bronchus

Extremities

Diminution or absence of pulses is found in up to 40% of patients, and occurs due to occlusion of a major aortic branch. For this reason it is critical to assess the pulse and blood pressure in both arms. The iliac arteries may be affected as well.

Neurologic

- Neurologic deficits such as coma, altered mental status, Cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and vagal episodes are seen in up to 20%.

- There can also be focal neurologic signs due to occlusion of a spinal artery. This condition is known as Anterior spinal artery syndrome or "Beck's syndrome".

Laboratory Findings

Routine blood work is usually not helpful and should not delay definitive diagnostic studies such as a CT scan and treatment. Hemolysis can be present as a result of blood in the false lumen. The presence of an elevated CK MB may indicate the presence of concomitant acute myocardial infarction (often a right coronary artery occlusion due to occlusion of the ostium of the RCA by the dissection). Hematuria may be present and may indicate the presence of renal infarction.

Electrocardiogram

ST elevation myocardial infarction (MI) due to occlusion by the dissection of the coronary artery at its ostium may be present. The right coronary artery tends to be involved more frequently than the left coronary artery. Electrical alternans may be present in the setting of a pericardial effusion should the dissection have extended into the pericardium.

Chest X-ray

An increased aortic diameter is the most common finding on chest X ray, and is observed in up to 84% of patients. A widened mediastinum is the next most common finding, and is observed in 15-20% of patients. The chest X-Ray is normal in 17% of patients. A pleural effusion (hemothorax) in the absence of congestive heart failure can be another sign of aortic dissection.

A General Approach to Imaging to Diagnose Aortic Dissection

There are a wide variety of imaging studies that can be used to diagnose aortic dissection, but in general, transesophageal imaging is the imaging modality of choice in the acutely ill patient and MRI is the imaging modality of choice in the assessment of longstanding aortic disease in a patient who has chronic chest pain who is hemodynamically stable or for the evaluation of a chronic dissection.

Use of Transesophageal Echo Imaging in the Acute Setting

In the management of the acute patient with suspected aortic dissection, a transesophageal echo performed acutely in the emergency room is the preferred approach. If the patient is hemodynamically unstable, then a transesophageal echo can be performed in the operating room as the patient after the patient has been induced and is being prepared for surgery.

Use of MRI Imaging in the Absence of Acute Disease

MRI is the imaging modality of choice in the assessment of

- A patient who has chronic chest pain who is hemodynamically stable

- A chronic dissection

Use of CT Scanning

A CT scan can be used if neither a TEE nor MRI is available in a timely fashion, or if there is a contraindication to their performance. An example would be after hours in an emergency room setting. If the results of the CT scan are non-diagnostic, they TEE or MRI should be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Use of Aortography

Aortography is rarely used in the modern era. It can be used of the other imaging modalities are not available or are inconclusive.

Use of Coronary Angiography

Pre-operative angiography has not been associated with improved outcomes in retrospective analyses. It is reasonable to perform coronary angiography in the following scenarios:

- Age over 60 years

- Presence of CAD risk factors

- History of prior myocardial infarction

Medical Therapy

Type A dissections of the proximal aorta are generally managed with operative repair whereas Type B dissections of the descending aorta are generally managed medically. Even patients who are undergoing operative repair require optimal medical management. The two goals in the medical management of aortic dissection are to reduce blood pressure and to reduce the oscillatory shear on the wall of the aorta (the shear-force dP/dt or force of ejection of blood from the left ventricle). The target blood pressure should be a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 60 to 75 mmHg.

Step 1: Urgent Surgical Consultation

- Simultaneous with the initiation of medical therapy as described below, urgent surgical consultation should be required regarding the potential need for operative repair of the dissection. Type A dissections of the proximal aorta are generally managed with operative repair whereas Type B dissections of the descending aorta are generally managed medically. Even patients who are undergoing operative repair require optimal medical management as described in the steps below.

Step 2: Rate Control

- The initial step in the medical management of the patient with aortic dissection is rate control. Rate control reduces oscillatory sheer stress as well as blood pressure. Rate control should be accomplished before vasodilators are administered in so far as vasodilators can increase oscillatory sheer stress.

- All patients should have an arterial line in the arm with the higher BP for accurate monitoring.

- Intravenous beta blockers can be administered and titrated to a heart rate of 60 bpm or less. The systolic blood pressure is kept at the lowest level that maintains adequate perfusion. Labetalol is an ideal agent in so far as it has both alpha and beta blocking properties. Initial treatment usually involves either Labetalol (a 20 mg bolus followed by 20-80mg every 10 minutes to a total dose of 300 mg, or as an infusion of 0.5 to 2 mg/min) or Propranolol (1 to 10 mg load followed by 3mg/hr) with the goal being a heart rate of 60 beats per minutes. Lopressor can also be administered.

- If there is an absolute contraindication to the administration of beta blockers than a nondihydropyridine calcium channel–blocking can be administered as an alternative for rate control. The calcium channel blockers typically used are verapamil and diltiazem, because of their combined vasodilator and negative inotropic effects.

- If aortic insufficiency is present, then beta blocker administration should be undertaken carefully as prolonging the diastolic filling period may increase the magnitude of aortic regurgitation.

- Pain control with morphine is important in so far as it reduces sympathetic tone, heart rate and blood pressure.

Step 3: Blood Pressure Control

- Vasodilator administration should only be undertaken after the heart rate is controlled. If the heart rate is not controlled, the administration of vasodilators may cause reflex tachycardia, and cause further expansion of the dissection.

- If the systolic blood pressure remains above 120 mm Hg, then an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor should be administered to further reduce the blood pressure. If this is ineffective, then the administration of parenteral vasodilators should be considered.

- If the heart rate is controlled, and the systolic blood pressure (SBP) is > 100 mmHg with adequate mentation and urine output, Sodium Nitroprusside can be administered at a dose of 0.25 – 0.5 ug/kg/min. Nitroprusside should never be administered prior to beta blockade, as the hypotension can result in a reflex tachycardia.

- The target blood pressure should be a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 60 to 75 mmHg.

- If the individual has refractory hypertension (persistent hypertension on the maximum doses of three different classes of antihypertensive agents), involvement of the renal arteries in the aortic dissection plane should be considered.

Step 4: Operative Repair Versus Medical Therapy

- Acute thoracic aortic dissection of the proximal ascending aorta (Type A dissections) should be urgently evaluated for emergent surgical repair given the increased risk of associated morbid / mortal complications such as aortic rupture.

- Acute thoracic aortic dissection of the descending aorta (Type B dissection) should be managed medically unless and of the following morbid / mortal complications develop:

- Malperfusion syndrome

- Further propagation of the dissection

- Further rapid aneurysm expansion

- Blood pressure lability suggestive of renal artery involvement

- For patients with DeBakey III or Daily B dissections, medical therapy offers an > 80% survival rate.

Step 5: Chronic Therapy

- In order to prevent recurrence and improve the patient's long term prognosis, smoking cessation, aggressive blood pressure control, and aggressive lipid-lowering therapy are essential. The relative risk of late rupture of an aortic aneurysm is 10 times higher in individuals who have uncontrolled hypertension, compared to individuals with a systolic pressure below 130 mmHg.

Surgery

Any dissection that involves the ascending aorta is considered a surgical emergency, and urgent surgical consultation is recommended. There is a 90% 3-month mortality among patients with a proximal aortic dissection who do not undergo surgery. These patients can rapidly develop acute aortic insufficiency (AI), tamponade or myocardial infarction (MI).

Contraindications to the Operative Repair of a Type A Dissection

Even acute MI in the setting of dissection is not a surgical contraindication. Acute hemorrhagic stroke is, however, a relative contraindication, due to the necessity of intraoperative heparinization.

Surgical Indications for Operative Repair of a Type B Dissection

Dissections involving only the descending aorta can generally be managed medically, but indications for surgery include the following:

- Progression of the dissection

- Continued hemorrhage into the pleural or retroperitoneal space

Surgical Complications Following Repair of a Type Be Dissection

- Spinal cord ischemia and paralysis.

Surgical Risk Factors

Risk factors associated with increased surgical mortality include the following:

- Rrenal insufficiency

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Renal ischemia

- Pericardial tamponade

- Underlying pulmonary disease

Surgical Procedure

Surgical therapy involves excision of the intimal tear, obliteration of the proximal entry site into the false lumen, and reconstitution of the aorta with placement of a synthetic graft. AI can be corrected by resuspension of the native valve, or by aortic valve replacement (AVR).

References

- ↑ DeBakey ME, Henly WS, Cooley DA, Morris GC Jr, Crawford ES, Beall AC Jr. Surgical management of dissecting aneurysms of the aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1965;49:130-49. PMID 14261867.

- ↑ Daily PO, Trueblood HW, Stinson EB, Wuerflein RD, Shumway NE. Management of acute aortic dissections. Ann Thorac Surg 1970;10:237-47. PMID 5458238.

- ↑ Increased maternal cardiovascular mortality associated with pregnancy in women with Turner syndrome.

- ↑ Saner, H.E., et al., Aortic dissection presenting as Pericarditis. Chest, 1987. 91(1): p. 71-4. PMID 3792088

- ↑ Rosman, H.S., et al., Quality of history taking in patients with aortic dissection. Chest, 1998. 114(3): p. 793-5. PMID 9743168

- ↑ Hagan, P.G., et al., The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA, 2000. 283(7): p. 897-903. PMID 10685714

- ↑ von Kodolitsch, Y., A.G. Schwartz, and C.A. Nienaber, Clinical prediction of acute aortic dissection. Arch Intern Med, 2000. 160(19): p. 2977-82. PMID 11041906

- ↑ Gwinnutt, C., Driscoll, P. (Eds) (2003) (2nd Ed.) Trauma Resuscitation: The Team Approach. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1859960097

- ↑ Dolan, B., Holt, L. (2000). Accident & Emergency: Theory into practice. London: Bailliere Tindall ISBN 978-0702022395