Trimethylaminuria

|

WikiDoc Resources for Trimethylaminuria |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Trimethylaminuria Most cited articles on Trimethylaminuria |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Trimethylaminuria |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Cochrane Collaboration on Trimethylaminuria |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Trimethylaminuria at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Trimethylaminuria Clinical Trials on Trimethylaminuria at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Trimethylaminuria NICE Guidance on Trimethylaminuria

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Trimethylaminuria Discussion groups on Trimethylaminuria Patient Handouts on Trimethylaminuria Directions to Hospitals Treating Trimethylaminuria Risk calculators and risk factors for Trimethylaminuria

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Trimethylaminuria |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief:

| Trimethylaminuria | |

| |

|---|---|

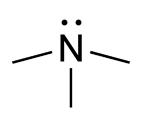

| Trimethylamine | |

| ICD-10 | E88.8 |

| ICD-9 | 270.8 |

| OMIM | 602079 |

| DiseasesDB | 4835 |

Overview

Trimethylaminuria (TMAU), also known as fish odor syndrome or fish malodor syndrome[1], is a rare metabolic disorder that causes a defect in the normal production of the enzyme Flavin containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3).[2][3] When FMO3 is not working correctly or if not enough enzyme is produced, the body loses the ability to properly breakdown trimethylamine (TMA) from precursor compounds in food into trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) through a process called N-oxygenation. Trimethylamine then builds up and is released in the person's sweat, urine, and breath, giving off a strong fishy odor.

Historical Perspective

The first clinical case of TMAU was described in 1970 in the medical journal The Lancet,[4] but literary references go back more than a thousand years. Shakespeare's Tempest describes the outcast Caliban, "He smells like a fish; a very ancient and fish-like smell...". Hindu folklore mentions in the epic Mahabharata (compiled around 400 AD) a maiden who "grew to be comely and fair, but a fishy odor ever clung to her."

Classification

Pathophysiology

Genetics

Most cases of trimethylaminuria appear to be inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means two copies of the gene in each cell are altered. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder are carriers of one copy of the altered gene. Carriers may have mild symptoms of trimethylaminuria or experience temporary episodes of fish-like body odor.

Mutations in the FMO3 gene, which is found on the long arm of chromosome 1, cause trimethylaminuria. The FMO3 gene makes an enzyme that breaks down nitrogen-containing compounds from the diet, including trimethylamine. This compound is produced by bacteria in the intestine as they digest proteins from eggs, meat, soy, and other foods. Normally, the FMO3 enzyme converts fishy-smelling trimethylamine into trimethylamine N-oxide which has no odor. If the enzyme is missing or its activity is reduced because of a mutation in the FMO3 gene, trimethylamine is not broken down and instead builds up in the body. As the compound is released in a person's sweat, urine, and breath, it causes the strong odor characteristic of trimethylaminuria. Researchers believe that stress and diet also play a role in triggering symptoms.

There are more than 40 known mutations associated with TMAU.[5][6] Loss-of-function mutations, nonsense mutations, and missense mutations are three of the most common. Nonsense and missense mutations cause the most severe phenotypes. Although FMO3 mutations account for most known cases of trimethylaminuria, some cases are caused by other factors. A fish-like body odor could result from an excess of certain proteins in the diet or from an increase in bacteria that normally break down trimethylamine in the digestive system. A few cases of the disorder have been identified in adults with liver damage caused by hepatitis.

The evolution of the FMO3 gene has recently been studied including the evolution of some mutations associated with TMAU. [7]

Causes

Trimethylamine builds up in the body of patients with trimethylaminuria. The trimethylamine gets released in the person's sweat, urine, reproductive fluids, and breath, giving off a strong fishy odor. Some people with trimethylaminuria have a strong odor all the time, but most have a moderate smell that varies in intensity over time. Individuals with this condition do not have any physical symptoms, and typically appear healthy.[8]

The condition seems to be more common in women than men, but scientists don't know why. Scientists suspect that female sex hormones, such as progesterone and/or estrogen, aggravate symptoms. There are several reports that the condition worsens around puberty. In women, symptoms can worsen just before and during menstrual periods, after taking oral contraceptives, and around menopause.[8]

This odor varies depending on many known factors, including diet, hormonal changes, other odors in the space, and individual sense of smell.

Differentiating Trimethylaminuria from Other Diseases

Epidemiology and Demographics

Incidence

TMAU is a life-disruptive disorder caused by both genetic and environmental factors. Living with TMAU is challenging, and it can adversely affect the livelihood of adults who have it and their families. Children with the condition could face rejection or a lack of understanding from peers during school or at play. There are various online support groups that have been created to help those in with malodor issues such as TMAU. The Yahoo TMAU support group [2] is listed in the National Institute of Healths publication "Learning About Trimethylaminuria" [3].

Risk Factors

Screening

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

Natural History

Complications

Prognosis

Diagnosis

Measurement of urine for the ratio of trimethylamine to trimethylamine oxide is the standard screening test. A blood test is available to provide genetic analysis. The prominent enzyme responsible for TMA N-oxygenation is coded by the FMO3 gene.

A similar test can be used to identify carriers of this condition - those individuals who carry one copy of a mutated gene but do not have symptoms. In this case, the person would be given a high dose of choline (one of the precursors of trimethylamine) and then have their urine tested for elevated levels of trimethylamine.

TMAU is a rare disorder. There used to be very limited medical knowledge readily available about most rare disorders or how to get tested for them. However, health care professionals can now get helpful information from genetic and rare disorder databases.

Diagnostic Criteria

History and Symptoms

Physical Examination

Laboratory Findings

Imaging Findings

Other Diagnostic Studies

Treatment

Currently, there is no cure and treatment options are limited. Although there is no perfect cure for trimethylaminuria, it is possible for some people with this condition to live relatively normal, healthy lives without the fear of being shunned because of their unpleasant odor. Getting tested is an important first step. Ways of reducing the odor include:

- Avoiding foods such as eggs, legumes, certain meats, fish, and foods that contain choline, carnitine, nitrogen, and sulfur

- Taking low doses of antibiotics to reduce the amount of bacteria in the gut

- Using slightly acidic detergents with a pH between 5.5 and 6.5

- At least one study[9] has suggested that the daily intake of charcoal and/or copper chlorophyllin may be of significant use in improving the quality of life of individuals suffering mild forms of TMAU, the success rates vary:

- 85% of people tested completely lost their "fishy" odor

- 10% partially lost their odor

- 5% kept the scent

However, whilst they may be beneficial in some cases, many people in trimethylaminuria support groups who have tried charcoal and copper chlorophyllin have reported disappointing results.

Also helpful are:

- Behavioral counseling to help with depression and other psychological symptoms

- Genetic counseling to better understand their condition

Medical Therapy

Surgery

Prevention

Trimethylaminuria foundation

The Trimethylaminuria Foundation is a 501 3 (C) non-profit corporation. The address is P.O. BOX 3361, Grand Central Station, New York, NY, 10163. Telephone: 212-300-4168.

External links

This article incorporates public domain text from The U.S. National Library of Medicine and The National Human Genome Research Institute

- page on TMAU at Monell Chemical Senses Center

- story on TMAU at ABC Primetime

- http://health.groups.yahoo.com/group/Trimethylaminuria/ [Online Support Group]

- Tamara McLean, "Woman's fishy-smelling mystery solved" Austrailian News Site, (October 19, 2008 12:00am) (accessed 22 October 2008).

References

- ↑ Mitchell SC, Smith RL (2001). "Trimethylaminuria: the fish malodor syndrome". Drug Metab Dispos. 29 (4 Pt 2): 517–21. PMID 11259343.

- ↑ Treacy EP; et al. (1998). "Mutations of the flavin-containing monooxygenase gene (FMO3) cause trimethylaminuria, a defect in detoxication". Human Molecular Genetics. 7 (5): 839–45. doi:10.1093/hmg/7.5.839. PMID 9536088.

- ↑ Zschocke J, Kohlmueller D, Quak E, Meissner T, Hoffmann GF, Mayatepek E (1999). "Mild trimethylaminuria caused by common variants in FMO3 gene". Lancet. 354 (9181): 834–5. PMID 10485731.

- ↑ Humbert JA, Hammond KB, Hathaway WE. (1970). "Trimethylaminuria: the fish-odour syndrome". Lancet. 2 (7676): 770–1. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(70)90241-2. PMID 4195988.

- ↑ Hernandez D, Addou S, Lee D, Orengo C, Shephard EA, Phillips IR (2003). "Trimethylaminuria and a human FMO3 mutation database". Hum Mutat. 22 (3): 209–13. doi:10.1002/humu.10252. PMID 12938085.

- ↑ Furnes B, Feng J, Sommer SS, Schlenk D (2003). "Identification of novel variants of the flavin-containing monooxygenase gene family in African Americans". Drug Metab Dispos. 31 (2): 187–93. doi:10.1124/dmd.31.2.187. PMID 12527699.

- ↑ Allerston CK, Shimizu M, Fujieda M, Shephard EA, Yamazaki H, Phillips IR (2007). "Molecular evolution and balancing selection in the flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 gene (FMO3)". Pharmacogenet Genomics. 17 (10): 827–39. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e328256b198. PMID 17885620.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 genome.gov | Learning About Trimethylaminuria

- ↑ Yamazaki H, Fujieda M, Togashi M; et al. (2004). "Effects of the dietary supplements, activated charcoal and copper chlorophyllin, on urinary excretion of trimethylamine in Japanese trimethylaminuria patients". Life Sci. 74 (22): 2739–47. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.022. PMID 15043988.

de:Trimethylaminurie nl:Trimethylaminuria nds:Trimethylaminurie sv:Trimetylaminuri