Hashimoto's thyroiditis

| Hashimoto's thyroiditis | |

| |

|---|---|

| Histology | |

| ICD-10 | E06.3 |

| ICD-9 | 245.2 |

| OMIM | 140300 |

| DiseasesDB | 5649 |

| MeSH | D050031 |

|

Hashimoto's thyroiditis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Hashimoto's thyroiditis On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Hashimoto's thyroiditis |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Hashimoto's thyroiditis |

For patient information click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Synonyms and Related Keywords: Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis; autoimmune thyroiditis; struma lymphomatosa

Historical Perspective

Also known as Hashimoto's disease, Hashimoto's thyroiditis is named after the Japanese physician Hashimoto Hakaru (1881−1934) of the medical school at Kyushu University,[1] who first described (He described four patients with a chronic disorder of the thyroid, which he termed struma lymphomatosa.

The thyroid glands of these patients were characterized by diffuse lymphocytic infiltration, fibrosis, parenchymal atrophy, and an eosinophilic change in some of the acinar cells) the symptoms in 1912 in a German publication [2].

Pathophysiology

Hashimoto's thyroiditis is characterized by Iymphocytic infiltration of the thyroid gland and production of antibodies that recognize thyroid-specific antigens. It is currently thought that the disease is caused by abnormal suppressor T-lymphocyte function which results in a localized cell-mediated immune response directed toward the thyroid parenchymal cells. The pathogenesis is not completely understood (In contrast Graves' disease is caused by production of antibodies that mimic the action of thyroid-stimulating hormone, and nutritional goiter is caused by iodine deficiency).

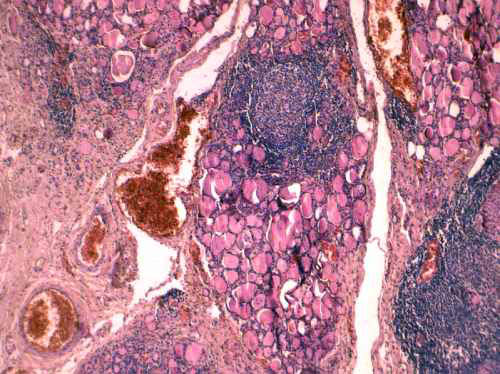

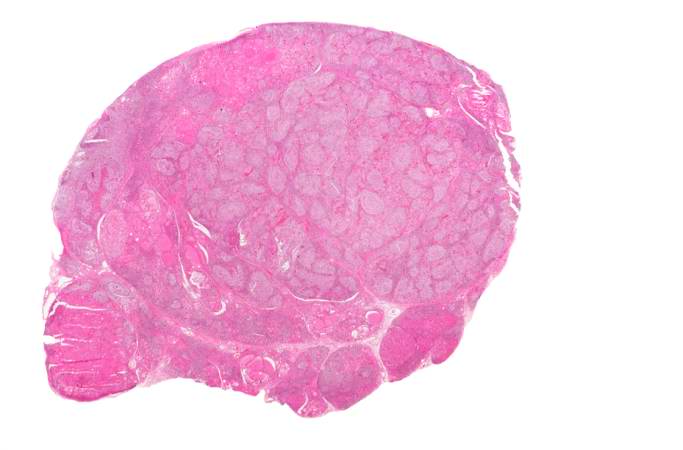

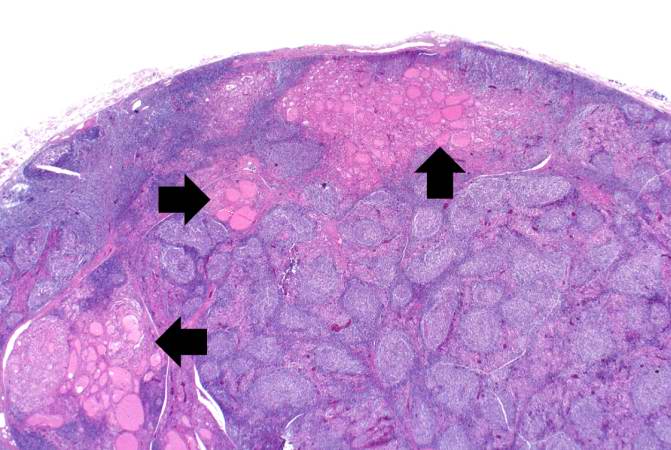

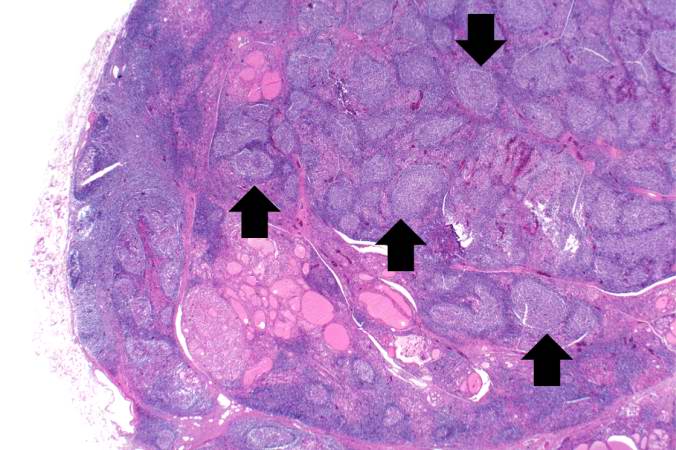

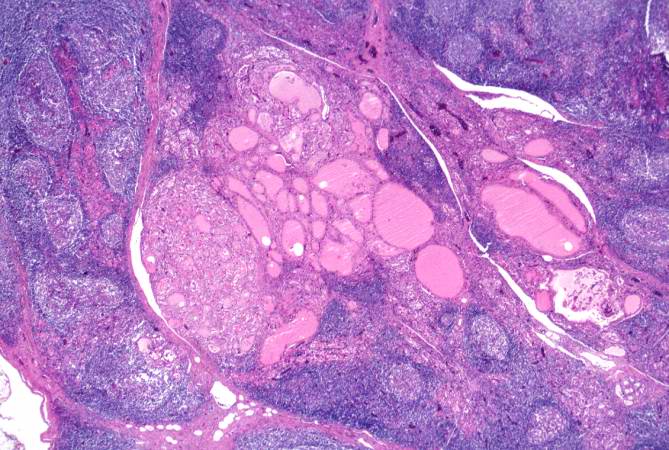

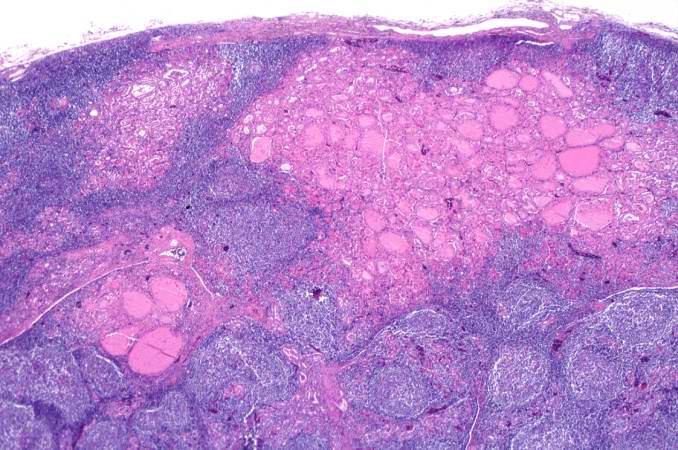

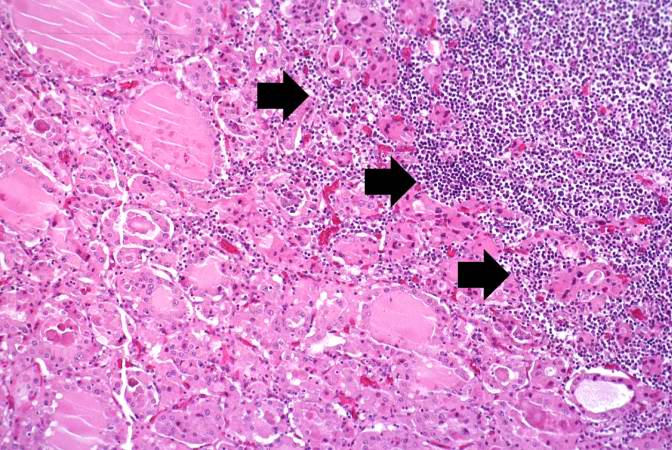

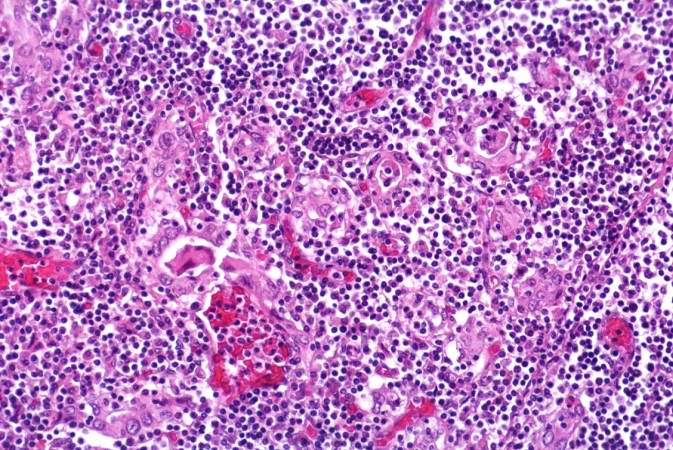

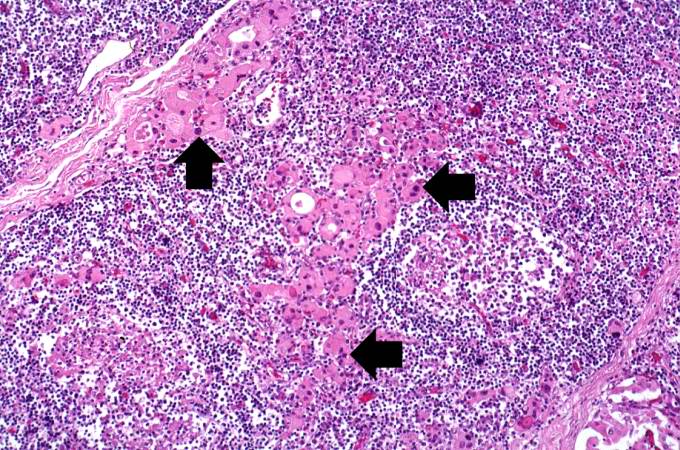

The gland is usually diffusely enlarged, firm, and slightly lobular. The capsule is intact, and the cut surface is light tan and has a slight lobular pattern. Microscopically there is massive infiltration of the thyroid gland by lymphocytes and plasma cells. Germinal centers can often be seen in the gland. Thyroid follicles are usually absent and the few remaining follicles are devoid of colloid.

Genetics

A family history of thyroid disorders is common, with the HLA-DR5 gene most strongly implicated conferring a relative risk of 3 in the UK.The genes implicated vary in different ethnic groups and the incidence is increased in patients with chromosomal disorders, including Turner, Down's, and Klinefelter's syndromes.

Associated Conditions

Hashimoto's disease may, in rare cases, be associated with other endocrine disorders caused by the immune system. Hashimoto's disease can occur with adrenal insufficiency and type 1 diabetes. In these cases, the condition is called type 2 polyglandular autoimmune syndrome (PGA II).

Less commonly, Hashimoto's disease occurs as part of a condition called type 1 polyglandular autoimmune syndrome (PGA I), along with:

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Fungal infections of the mouth and nails

- Hypoparathyroidism

Gross Pathology

At autopsy, significant subarachnoid hemorrhage from the ruptured berry aneurysm was documented. In addition, the thyroid gland was mildly enlarged and firm. On cut section the tissue was slightly pale.

Microscopic Pathology

Epidemiology and Demographics

This disorder is believed to be the most common cause of primary hypothyroidism in North America. It occurs far more often in women than in men (10:1 to 20:1), and is most prevalent between 45 and 65 years of age.

In European countries an atrophic form of autoimmune thyroiditis (Ord's thyroiditis) is more common than Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

The disease begins slowly. It may take months or even years for the condition to be detected. Chronic thyroiditis is most common in women and people with a family history of thyroid disease. It affects between 0.1% and 5% of all adults in Western countries.

Various autoantibodies may be present against thyroid peroxidase, thyroglobulin and TSH receptors, although a small percentage of patients may have none of these antibodies present. A percentage of the population may also have these antibodies without developing Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

If untreated for an extended period, Hashimoto's thyroiditis may lead to muscle failure, including possible heart failure.

Diagnosis

Symptoms

In many cases, Hashimoto's thyroiditis usually results in hypothyroidism, although in its acute phase, it can cause a transient hyperthyroidism thyrotoxic state known as hashitoxicosis.

- Adolescent goiter

- Alternating hypo- and hyperthyroidism

- Euthyroidism and goiter

- Hypothyroidism

- Painless thyroiditis or silent thyroiditis

- Postpartum painless thyrotoxicosis

- Primary thyroid failure

- Subclinical hypothyroidism and goiter

(In alphabetical order) [3]

- Cold intolerance

- Constipation

- Depression

- Difficulty concentrating or thinking

- Dry skin

- Enlarged neck or presence of goiter

- Fatigue

- Hair loss

- Heavy and irregular periods

- Hyperthyroidism symptoms

- Hypothyroidism symptoms

- Infertility

- Lethargy

- Mania

- Memory loss

- Migraines

- Myxedema

- Panic attacks

- Puffy face

- Small or shrunken thyroid gland (late in the disease)

- Weight gain

- Weight loss

Other symptoms that can occur with this disease:

- Joint stiffness

- Swelling of the face

Physical Examination

Appearance of the Patient

Vital Signs

Skin

Head

- Puffy face

Throat

- Enlarged neck or presence of goiter

- Small or shrunken thyroid gland (late in the disease

Neurologic

- Slowed speech

- Slowed reflexes

Laboratory Findings

Electrolyte and Biomarker Studies

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Free T3 and Free T4

- Anti-thyroglobulin antibodies (anti-Tg)

- Anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO)

- Anti-microsomal antibodies can help obtain an accurate diagnosis.[4] Earlier assessment of the patient may present with elevated levels of thyroglobulin owing to the transient thyrotoxicosis as inflammation within the thyroid causes damage to the integrity of thyroid follicle storage of thyroglobulin; TSH is concomitantly decreased.[5]

- Diagnosis is made by detecting elevated levels of Anti-TPO antibodies in the serum.

Treatment

Pharmacotherapy

Chronic Pharmacotherapies

Hypothyroidism caused by Hashimoto's Thyroiditis is treated with thyroid hormone replacement. A small pill taken once a day should be able to keep the thyroid hormone levels normal. This medicine will, in most cases, need to be taken for the rest of the patient's life.

Case Studies

Case#1

References

- ↑ Template:WhoNamedIt

- ↑ H. Hashimoto: Zur Kenntnis der lymphomatösen Veränderung der Schilddrüse (Struma lymphomatosa). Archiv für klinische Chirurgie, Berlin, 1912, 97: 219−248.

- ↑ Ladenson P, Kim M. Thyroid. In: Goldman L and Ausiello D, eds. Goldman: Cecil Medicine. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa:Saunders; 2007:chap 244.

- ↑ Giannini, AJ (1986). The Biological Foundations of Clinical Psychiatry. New Hyde Park, NY: Medical Examination Publishing Company. pp. 193–198. ISBN 0-87488-449-7.

- ↑ Simmons, PJ (1998). "Antigen-presenting dendritic cells as regulators of the growth of thyrocytes: a role of interleukin-1beta and interleukin-6". Endocrinology. 139 (7): 3158–3186. doi:10.1210/en.139.7.3148. PMID 9645688. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help)