Restrictive cardiomyopathy: Difference between revisions

| Line 314: | Line 314: | ||

===Laboratory Findings=== | ===Laboratory Findings=== | ||

*The laboratory findings depends on the cause of the cardiomyopathy.<ref name="pmid15936624">{{cite journal |vauthors=Leya FS, Arab D, Joyal D, Shioura KM, Lewis BE, Steen LH, Cho L |title=The efficacy of brain natriuretic peptide levels in differentiating constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy |journal=J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. |volume=45 |issue=11 |pages=1900–2 |date=June 2005 |pmid=15936624 |doi=10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.050 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid2991971">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ainslie GM, Benatar SR |title=Serum angiotensin converting enzyme in sarcoidosis: sensitivity and specificity in diagnosis: correlations with disease activity, duration, extra-thoracic involvement, radiographic type and therapy |journal=Q. J. Med. |volume=55 |issue=218 |pages=253–70 |date=June 1985 |pmid=2991971 |doi= |url=}}</ref> | *The [[laboratory]] findings depends on the [[Causes|cause]] of the cardiomyopathy.<ref name="pmid15936624">{{cite journal |vauthors=Leya FS, Arab D, Joyal D, Shioura KM, Lewis BE, Steen LH, Cho L |title=The efficacy of brain natriuretic peptide levels in differentiating constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy |journal=J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. |volume=45 |issue=11 |pages=1900–2 |date=June 2005 |pmid=15936624 |doi=10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.050 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid2991971">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ainslie GM, Benatar SR |title=Serum angiotensin converting enzyme in sarcoidosis: sensitivity and specificity in diagnosis: correlations with disease activity, duration, extra-thoracic involvement, radiographic type and therapy |journal=Q. J. Med. |volume=55 |issue=218 |pages=253–70 |date=June 1985 |pmid=2991971 |doi= |url=}}</ref> | ||

*Hematocrit | *[[Hematocrit]], [[Electrolyte|serum electrolytes]], [[blood urea nitrogen]] (BUN), [[creatinine]], 24 hr urine total protein, and [[liver function]] should be assessed. | ||

*Arterial blood gas (ABG) should be checked | *[[Arterial blood gas]] ([[ABG]]) should be checked for possibility of [[hypoxia]]. | ||

*Serum brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and troponin T are indicative of the heart failure. | *[[Brain natriuretic peptide|Serum brain natriuretic peptide]] ([[BNP]]) or [[N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide|N-terminal pro-b-type natriuretic peptide]] ([[NT-proBNP]]) and [[troponin T]] are indicative of the [[heart failure]]. | ||

*Other Specific lab findings will depend upon the cause (angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in sarcoidosis, complete blood count (CBC) with peripheral smear helping to establish eosinophilia in hypereosinophilic syndromes, serum iron concentrations, total iron-binding capacity and ferritin levels in hemocromatosis, immunoglobulin free light κ, λ chain testing, and serum and urine immunofixation in amyloidosis, etc. | *Other Specific lab findings will depend upon the cause (angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in sarcoidosis, complete blood count (CBC) with peripheral smear helping to establish eosinophilia in hypereosinophilic syndromes, serum iron concentrations, total iron-binding capacity and ferritin levels in hemocromatosis, immunoglobulin free light κ, λ chain testing, and serum and urine immunofixation in amyloidosis, etc. | ||

| Line 349: | Line 349: | ||

==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

===Medical Therapy=== | ===Medical Therapy=== | ||

*Restrictive cardiomyopathy has no definitive treatment. But However, the ones directed at individual causes have been proven to be effective.<ref name="pmid29270320">{{cite journal |vauthors=Rammos A, Meladinis V, Vovas G, Patsouras D |title=Restrictive Cardiomyopathies: The Importance of Noninvasive Cardiac Imaging Modalities in Diagnosis and Treatment-A Systematic Review |journal=Radiol Res Pract |volume=2017 |issue= |pages=2874902 |date=2017 |pmid=29270320 |pmc=5705874 |doi=10.1155/2017/2874902 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid24976920">{{cite journal |vauthors=Sisakian H |title=Cardiomyopathies: Evolution of pathogenesis concepts and potential for new therapies |journal=World J Cardiol |volume=6 |issue=6 |pages=478–94 |date=June 2014 |pmid=24976920 |pmc=4072838 |doi=10.4330/wjc.v6.i6.478 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid20141097">{{cite journal |vauthors=Wexler RK, Elton T, Pleister A, Feldman D |title=Cardiomyopathy: an overview |journal=Am Fam Physician |volume=79 |issue=9 |pages=778–84 |date=May 2009 |pmid=20141097 |pmc=2999879 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid28928965">{{cite journal |vauthors=Alvarez P, Tang WW |title=Recent Advances in Understanding and Managing Cardiomyopathy |journal=F1000Res |volume=6 |issue= |pages=1659 |date=2017 |pmid=28928965 |pmc=5590086 |doi=10.12688/f1000research.11669.1 |url=}}</ref> | *Restrictive cardiomyopathy has no definitive treatment. But However, the ones directed at individual [[causes]] have been proven to be effective.<ref name="pmid29270320">{{cite journal |vauthors=Rammos A, Meladinis V, Vovas G, Patsouras D |title=Restrictive Cardiomyopathies: The Importance of Noninvasive Cardiac Imaging Modalities in Diagnosis and Treatment-A Systematic Review |journal=Radiol Res Pract |volume=2017 |issue= |pages=2874902 |date=2017 |pmid=29270320 |pmc=5705874 |doi=10.1155/2017/2874902 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid24976920">{{cite journal |vauthors=Sisakian H |title=Cardiomyopathies: Evolution of pathogenesis concepts and potential for new therapies |journal=World J Cardiol |volume=6 |issue=6 |pages=478–94 |date=June 2014 |pmid=24976920 |pmc=4072838 |doi=10.4330/wjc.v6.i6.478 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid20141097">{{cite journal |vauthors=Wexler RK, Elton T, Pleister A, Feldman D |title=Cardiomyopathy: an overview |journal=Am Fam Physician |volume=79 |issue=9 |pages=778–84 |date=May 2009 |pmid=20141097 |pmc=2999879 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid28928965">{{cite journal |vauthors=Alvarez P, Tang WW |title=Recent Advances in Understanding and Managing Cardiomyopathy |journal=F1000Res |volume=6 |issue= |pages=1659 |date=2017 |pmid=28928965 |pmc=5590086 |doi=10.12688/f1000research.11669.1 |url=}}</ref> | ||

*The main purpose of treatment in restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is to reduce symptoms by decreasing the elevated filling pressures without significantly lowering the cardiac output. | *The main purpose of treatment in restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is to reduce [[symptoms]] by decreasing the elevated filling pressures without significantly lowering the [[cardiac output]]. | ||

*Pharmacologic therapy may include: | *[[Pharmacologic]] therapy may include: | ||

**Beta blockers | **[[Beta blockers]] | ||

**Amiodarone | **[[Amiodarone]] | ||

**Cardioselective calcium channel blockers | **Cardioselective [[calcium channel blockers]] | ||

**Diuretics | **[[Diuretics]] | ||

**Anticoagulants for patients with atrial fibrillation | **[[Anticoagulants]] for [[patients]] with [[atrial fibrillation]] | ||

**Digoxin (use with caution) | **[[Digoxin]] (use with caution) | ||

**Melphalan (for antiplasma cell therapy in systemic amyloidosis) | **[[Melphalan]] (for antiplasma cell therapy in systemic [[amyloidosis]]) | ||

**Chemotherapy (in amyloidosis) | **[[Chemotherapy]] (in [[amyloidosis]]) | ||

**Corticosteroids, cytotoxic agents (eg, hydroxyurea), and interferon (in Loeffler endocarditis) | **[[Corticosteroids]], [[Cytotoxic drugs|cytotoxic]] agents (eg, [[hydroxyurea]]), and [[interferon]] (in [[Loeffler endocarditis]]) | ||

**Chelation therapy or therapeutic phlebotomy (in hemochromatosis) | **[[Chelation therapy]] or therapeutic [[phlebotomy]] (in [[hemochromatosis]]) | ||

*Other treatments: | *Other treatments: | ||

**Pacemaker implantation | **[[Pacemaker]] implantation | ||

**Endomyocardectomy | **Endomyocardectomy | ||

**Cardiac transplantation | **[[Cardiac transplantation]] | ||

**Novel approches (eg, RNA interference or gene silencing molecules that target abnormal protein production in familial amyloidosis) | **Novel approches (eg, [[RNA]] interference or [[gene silencing]] [[molecules]] that target abnormal [[protein]] production in [[familial amyloidosis]]) | ||

===Surgery=== | ===Surgery=== | ||

Revision as of 18:05, 7 January 2020

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JONXrVH4jQU%7C350}} |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Synonyms and keywords: Infiltrative cardiomyopathy; RCM; stiff heart; stiffening of the heart; heart stiffening; stiffened heart

Overview

Historical Perspective

- In 1957 for the first time Brigden coined the term ‘cardiomyopathy’ to describe group of uncommon, non-coronary myocardial diseases.[1][2][3]

- But later in 1961 Goodwin redefined cardiomyopathies as “myocardial diseases of unknown cause”. Infact he is the one who put them into 3 seperate entities “dilated, hypertrophic and restrictive”, which we are still using today.

- In 1980 World Health Organization (WHO) and International Society and Federation of Cardiology (ISFC) combinedly published a classification which included the three subgroups proposed by Goodwin.

Classification

- There is no established system for the classification of restrictive cardiomyopathy[4] [5][6][7][8]

- It may be classified into:

- Primary

- EMF(endomyocardial fibrosis)

- Loffler’s endocarditis

- Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy

- Secondary

- Infiltrative diseases(e.g., amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, and radiation carditis)

- Storage diseases (e.g., hemochromatosis, glycogen storage disorders, and Fabry’s disease)

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis

- The exact pathogenesis of restrictive cardiomyopathy is not completely understood[4].

- Mainly characterized by impaired ventricular filling and reduced diastolic volume of one or both ventricles, with either normal or near-normal systolic function.

- Hemodynamic abnormalities constitute the main pathological aspect of restrictive cardiomyopathy.

- The primary abnormality of restrictive cardiomyopathy is impaired myocardial relaxation along with interstitial fibrosis as well as calcifications.

- Restrictive filling can been seen which is due to higher diastolic pressure.

Genetics

Genes involved in the pathogenesis of restrictive cardiomyopathy include[9][10][11][12]:

- Cardiac genes for desmin, α-actin, troponin I and troponin T.

- Missense mutation (D190H) in the region of the cTnI gene (TNNI3).

- De novo mutations (R192H and K178E) in the TNNI3 gene.

- Mutations in the α-cardiac actin (ACTC), β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC), and cTnT (TNNT2) genes have been noticed to have etiological causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy.

Gross Pathology

On gross pathology, [feature1], [feature2], and [feature3] are characteristic findings of [disease name].

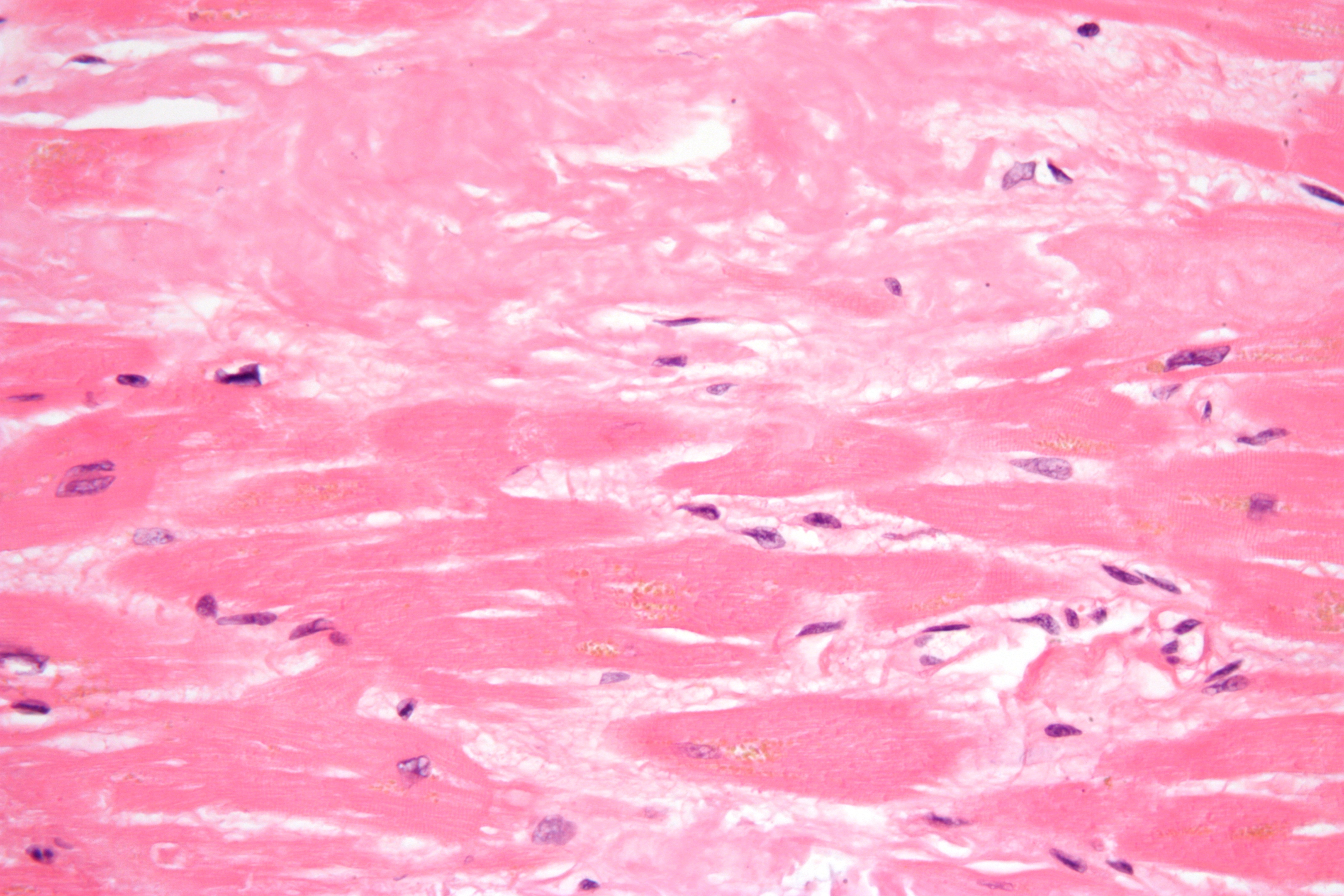

Microscopic Pathology

On microscopic histopathological analysis, [feature1], [feature2], and [feature3] are characteristic findings of [disease name].

Causes

The main Causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy are enlisted below:[13][14]

- Amyloidosis (AL, ATTR, SSA)

- Sarcoidosis

- Hemochromatosis

- Eosinophilic myocardial disease

- Idiopathic RCM

- Progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma)

- Postradiation therapy (Hodgkin's lymphoma, breast cancer etc)

- Anderson Fabry disease

- Danon's disease

- Friedreich's ataxia

- Diabetic cardiomyopathy (restrictive phenotype)

- Drug induced (anthracycline toxicity, methysergide, ergotamine, mercurial agents, etc.)

- Mucopolysaccharidoses (Hurler's cardiomyopathy)

- Myocardial oxalosis

- Wegener's granulomatosis

- Metastatic malignancies

Differentiating restrictive cardiomyopathy from Other Diseases

Restrictive cardiomyopathy should be differentiated from dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure ect [14],[13]

| Type of disease | History | Physical examination | Chest X-ray | ECG | 2D echo | Doppler echo | CT | MRI | Catheterization hemodynamics | Biopsy |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy[14][9][13] | Systemic disease (e.g., sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis). |

|

Atrial dilatation | Low QRS voltages (mainly amyloidosis), conduction disturbances, nonspecific ST abnormalities | ± Wall and valvular thickening, sparkling myocardium | Decreased variation in mitral and/or tricuspid inflow E velocity, increased hepatic vein inspiratory diastolic flow reversal, presence of mitral and tricuspid regurgitation | Normal pericardium | Measurement of iron overload, various types of LGE (late gadolinium enhancement) | LVEDP – RVEDP ≥ 5 mmHg

RVSP ≥ 55 mmHg RVEDP/RVSP ≤ 0.33 |

May reveal underlying cause. |

| Constrictive pericarditis[15][16][16] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy(HCM)[17][18] |

|

|

|

|

| |||||

| Dilated Cardiomyopathy[19][20][21][22] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Epidemiology and Demographics

Risk Factors

Screening

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

Natural History

- The symptoms of (disease name) usually develop in the first/ second/ third decade of life, and start with symptoms such as ___.

- The symptoms of (disease name) typically develop ___ years after exposure to ___.

- If left untreated, [#]% of patients with [disease name] may progress to develop [manifestation 1], [manifestation 2], and [manifestation 3].

Complications

- Common complications of restrictive cardiomyopathy include:

- Thromboembolism

- Rhythm abnormalities(dysrhythmias)

- Cardiac cirrhosis

- Heart failure

- Pulmonary hypertension

Prognosis

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) has the worst prognosis among all types of cardiomyopathies.

- Prognosis is generally poor, and the 2/5-year mortality rate of patients is approximately 50% and 70%, respectively.

- Depending on the extent of the [tumor/disease progression] at the time of diagnosis, the prognosis may vary. However, the prognosis is generally regarded as poor/good/excellent.

- The presence of [characteristic of disease] is associated with a particularly [good/poor] prognosis among patients with [disease/malignancy].

- [Subtype of disease/malignancy] is associated with the most favorable prognosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Study of Choice

History and Symptoms

- The majority of patients with [disease name] are asymptomatic.

OR

- The hallmark of [disease name] is [finding]. A positive history of [finding 1] and [finding 2] is suggestive of [disease name]. The most common symptoms of [disease name] include [symptom 1], [symptom 2], and [symptom 3].

- Symptoms of [disease name] include [symptom 1], [symptom 2], and [symptom 3].

History

Patients with [disease name]] may have a positive history of:

- [History finding 1]

- [History finding 2]

- [History finding 3]

Common Symptoms

Common symptoms of [disease] include:

- Dyspnea

- Fatigue

- Limited exercise capacity

- Palpitations

- Syncope

Less Common Symptoms

Less common symptoms of restrictive cardiomyopathy include

- Angina

Physical Examination

Physical examination of patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy is usually abnormal with characteristic findings in cardiovascular and pulmonary systems.

Appearance of the Patient

- Patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy usually appear normal.

Vital Signs

- High-grade / low-grade fever

- Hypothermia / hyperthermia may be present

- Tachycardia with regular pulse or (ir)regularly irregular pulse

- Bradycardia with regular pulse or (ir)regularly irregular pulse

- Tachypnea / bradypnea

- Kussmal respirations may be present in _____ (advanced disease state)

- Weak/bounding pulse / pulsus alternans / paradoxical pulse / asymmetric pulse

- High/low blood pressure with normal pulse pressure / wide pulse pressure / narrow pulse pressure

Skin

- Skin examination of patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy is usually normal.

HEENT

- HEENT examination of patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy is usually normal.

Neck

- Jugular venous distension is noted sometimes with kussmaul sign

- Hepatojugular reflux

Lungs

- Fine/coarse crackles upon auscultation of the lung bases/apices unilaterally/bilaterally

- Rhonchi

Heart

Abdomen

Back

- Back examination of patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy is usually normal.

Genitourinary

- Genitourinary examination of patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy is usually normal.

Neuromuscular

- Neuromuscular examination of patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy is usually normal.

Extremities

- Peripheral edema of the lower extremities

Laboratory Findings

- The laboratory findings depends on the cause of the cardiomyopathy.[23][24]

- Hematocrit, serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, 24 hr urine total protein, and liver function should be assessed.

- Arterial blood gas (ABG) should be checked for possibility of hypoxia.

- Serum brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and troponin T are indicative of the heart failure.

- Other Specific lab findings will depend upon the cause (angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in sarcoidosis, complete blood count (CBC) with peripheral smear helping to establish eosinophilia in hypereosinophilic syndromes, serum iron concentrations, total iron-binding capacity and ferritin levels in hemocromatosis, immunoglobulin free light κ, λ chain testing, and serum and urine immunofixation in amyloidosis, etc.

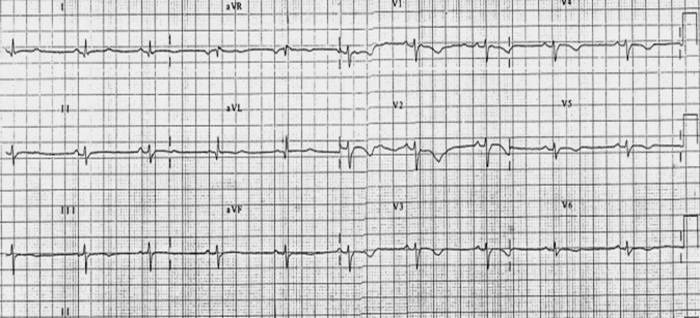

Electrocardiogram

Shown below is an example of restrictive cardiomyopathy with low voltage and flipped anterior T waves.

X-ray

A chest X-ray may show atrial dilatation most of the times.

Echocardiography and Ultrasound

Echocardiography may be helpful in the diagnosis of restrictive cardiomyopathy. Findings on an echocardiography suggestive of restrictive cardiomyopathy include:

- Normal or increased wall thickness

- Transmitral spectral Doppler often shows restrictive filling pattern.

- Marked left or biatrial dilatation usually as a consequence of chronically elevated filling pressures.

- Ejection fraction (EF) is normal or near normal.

- The main purpose of echo is the differential diagnosis between constrictive pericarditis(CP) and resrictive cardiomyopathy(RCM).

- Both present as heart failure with normal-sized ventricles and preserved EF, dilated atria, and doppler findings of increased filling pressure often seen in restrictive cardiomyopathy.

CT scan

MRI

- Magnetic Resonance imaging and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) is very helpful in providing information about anatomic structures, perfusion, ventricular function, as well as tissue characterization.[25][26]

- Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) depending on the pattern of scar formation can help the doctor in establishing the diagnosis to specific subtypes of restrictive cardiomyopathy(RCM).

- MRI can also quantify the myocardial iron load in patients with haemochromatosis or thalassemia who receive transfusions.

Other Imaging Findings

Other Diagnostic Studies

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy has no definitive treatment. But However, the ones directed at individual causes have been proven to be effective.[14][4][27][28]

- The main purpose of treatment in restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is to reduce symptoms by decreasing the elevated filling pressures without significantly lowering the cardiac output.

- Pharmacologic therapy may include:

- Beta blockers

- Amiodarone

- Cardioselective calcium channel blockers

- Diuretics

- Anticoagulants for patients with atrial fibrillation

- Digoxin (use with caution)

- Melphalan (for antiplasma cell therapy in systemic amyloidosis)

- Chemotherapy (in amyloidosis)

- Corticosteroids, cytotoxic agents (eg, hydroxyurea), and interferon (in Loeffler endocarditis)

- Chelation therapy or therapeutic phlebotomy (in hemochromatosis)

- Other treatments:

- Pacemaker implantation

- Endomyocardectomy

- Cardiac transplantation

- Novel approches (eg, RNA interference or gene silencing molecules that target abnormal protein production in familial amyloidosis)

Surgery

Primary Prevention

Secondary Prevention

References

- ↑ GOODWIN JF, GORDON H, HOLLMAN A, BISHOP MB (January 1961). "Clinical aspects of cardiomyopathy". Br Med J. 1 (5219): 69–79. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5219.69. PMC 1952892. PMID 13707066.

- ↑ BRIGDEN W (December 1957). "Uncommon myocardial diseases: the non-coronary cardiomyopathies". Lancet. 273 (7008): 1243–9. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(57)91537-4. PMID 13492617.

- ↑ "Report of the WHO/ISFC task force on the definition and classification of cardiomyopathies". Br Heart J. 44 (6): 672–3. December 1980. doi:10.1136/hrt.44.6.672. PMC 482464. PMID 7459150.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sisakian H (June 2014). "Cardiomyopathies: Evolution of pathogenesis concepts and potential for new therapies". World J Cardiol. 6 (6): 478–94. doi:10.4330/wjc.v6.i6.478. PMC 4072838. PMID 24976920.

- ↑ McCartan C, Mason R, Jayasinghe SR, Griffiths LR (2012). "Cardiomyopathy classification: ongoing debate in the genomics era". Biochem Res Int. 2012: 796926. doi:10.1155/2012/796926. PMC 3423823. PMID 22924131.

- ↑ Nakata M, Koga Y (January 2000). "[Definition and classification of cardiomyopathies and specific cardiomyopathies]". Nippon Rinsho (in Japanese). 58 (1): 7–11. PMID 10885280.

- ↑ Thiene G, Corrado D, Basso C (October 2004). "Cardiomyopathies: is it time for a molecular classification?". Eur. Heart J. 25 (20): 1772–5. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2004.07.026. PMID 15474691.

- ↑ Cecchi F, Tomberli B, Olivotto I (2012). "Clinical and molecular classification of cardiomyopathies". Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2012 (1): 4. doi:10.5339/gcsp.2012.4. PMC 4239818. PMID 25610835.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mogensen J, Kubo T, Duque M, Uribe W, Shaw A, Murphy R, Gimeno JR, Elliott P, McKenna WJ (January 2003). "Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy is part of the clinical expression of cardiac troponin I mutations". J. Clin. Invest. 111 (2): 209–16. doi:10.1172/JCI16336. PMC 151864. PMID 12531876.

- ↑ Burke MA, Cook SA, Seidman JG, Seidman CE (December 2016). "Clinical and Mechanistic Insights Into the Genetics of Cardiomyopathy". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68 (25): 2871–2886. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.079. PMC 5843375. PMID 28007147.

- ↑ Parvatiyar MS, Pinto JR, Dweck D, Potter JD (2010). "Cardiac troponin mutations and restrictive cardiomyopathy". J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010: 350706. doi:10.1155/2010/350706. PMC 2896668. PMID 20617149.

- ↑ Kostareva A, Gudkova A, Sjöberg G, Mörner S, Semernin E, Krutikov A, Shlyakhto E, Sejersen T (January 2009). "Deletion in TNNI3 gene is associated with restrictive cardiomyopathy". Int. J. Cardiol. 131 (3): 410–2. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.108. PMID 18006163.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Hong JA, Kim MS, Cho MS, Choi HI, Kang DH, Lee SE, Lee GY, Jeon ES, Cho JY, Kim KH, Yoo BS, Lee JY, Kim WJ, Kim KH, Chung WJ, Lee JH, Cho MC, Kim JJ (September 2017). "Clinical features of idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy: A retrospective multicenter cohort study over 2 decades". Medicine (Baltimore). 96 (36): e7886. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000007886. PMC 6393124. PMID 28885342.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Rammos A, Meladinis V, Vovas G, Patsouras D (2017). "Restrictive Cardiomyopathies: The Importance of Noninvasive Cardiac Imaging Modalities in Diagnosis and Treatment-A Systematic Review". Radiol Res Pract. 2017: 2874902. doi:10.1155/2017/2874902. PMC 5705874. PMID 29270320.

- ↑ Ramasamy V, Mayosi BM, Sturrock ED, Ntsekhe M (September 2018). "Established and novel pathophysiological mechanisms of pericardial injury and constrictive pericarditis". World J Cardiol. 10 (9): 87–96. doi:10.4330/wjc.v10.i9.87. PMC 6189073. PMID 30344956.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Biçer M, Özdemir B, Kan İ, Yüksel A, Tok M, Şenkaya I (November 2015). "Long-term outcomes of pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis". J Cardiothorac Surg. 10: 177. doi:10.1186/s13019-015-0385-8. PMC 4662820. PMID 26613929.

- ↑ Kubo T, Gimeno JR, Bahl A, Steffensen U, Steffensen M, Osman E, Thaman R, Mogensen J, Elliott PM, Doi Y, McKenna WJ (June 2007). "Prevalence, clinical significance, and genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with restrictive phenotype". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49 (25): 2419–26. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.061. PMID 17599605.

- ↑ Marian AJ, Braunwald E (September 2017). "Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Genetics, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Therapy". Circ. Res. 121 (7): 749–770. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311059. PMC 5654557. PMID 28912181.

- ↑ Francone M (2014). "Role of cardiac magnetic resonance in the evaluation of dilated cardiomyopathy: diagnostic contribution and prognostic significance". ISRN Radiol. 2014: 365404. doi:10.1155/2014/365404. PMC 4045555. PMID 24967294.

- ↑ McNally EM, Mestroni L (September 2017). "Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Genetic Determinants and Mechanisms". Circ. Res. 121 (7): 731–748. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309396. PMC 5626020. PMID 28912180.

- ↑ Tayal U, Prasad S, Cook SA (February 2017). "Genetics and genomics of dilated cardiomyopathy and systolic heart failure". Genome Med. 9 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/s13073-017-0410-8. PMC 5322656. PMID 28228157.

- ↑ Mitrut R, Stepan AE, Pirici D (2018). "Histopathological Aspects of the Myocardium in Dilated Cardiomyopathy". Curr Health Sci J. 44 (3): 243–249. doi:10.12865/CHSJ.44.03.07. PMC 6311227. PMID 30647944.

- ↑ Leya FS, Arab D, Joyal D, Shioura KM, Lewis BE, Steen LH, Cho L (June 2005). "The efficacy of brain natriuretic peptide levels in differentiating constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45 (11): 1900–2. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.050. PMID 15936624.

- ↑ Ainslie GM, Benatar SR (June 1985). "Serum angiotensin converting enzyme in sarcoidosis: sensitivity and specificity in diagnosis: correlations with disease activity, duration, extra-thoracic involvement, radiographic type and therapy". Q. J. Med. 55 (218): 253–70. PMID 2991971.

- ↑ Quarta G, Sado DM, Moon JC (December 2011). "Cardiomyopathies: focus on cardiovascular magnetic resonance". Br J Radiol. 84 Spec No 3: S296–305. doi:10.1259/bjr/67212179. PMC 3473912. PMID 22723536.

- ↑ Yalcinkaya E, Bugan B, Celik M, Yildirim E, Gursoy E (2014). "Cardiomyopathies: the value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging". Med Princ Pract. 23 (2): 191. doi:10.1159/000356379. PMC 5586852. PMID 24280689.

- ↑ Wexler RK, Elton T, Pleister A, Feldman D (May 2009). "Cardiomyopathy: an overview". Am Fam Physician. 79 (9): 778–84. PMC 2999879. PMID 20141097.

- ↑ Alvarez P, Tang WW (2017). "Recent Advances in Understanding and Managing Cardiomyopathy". F1000Res. 6: 1659. doi:10.12688/f1000research.11669.1. PMC 5590086. PMID 28928965.