Congestive heart failure epidemiology and demographics

| Resident Survival Guide |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]; Saleh El Dassouki, M.D [3]; Atif Mohammad, M.D. ;Seyedmahdi Pahlavani, M.D. [4]; Edzel Lorraine Co, D.M.D., M.D. [5]

Overview

Heart failure affects close to 5 million people in the United States of America and each year close to 500,000 new cases are diagnosed. Congestive heart failure is responsible for a significant portion of the healthcare budget, and more than 50% of patients seek re-admission within 6 months after treatment and the average duration of hospital stay is 6 days. In 2001, nearly 53,000 patients died of heart failure as a primary cause.

Epidemiology and Demographics

Prevalence

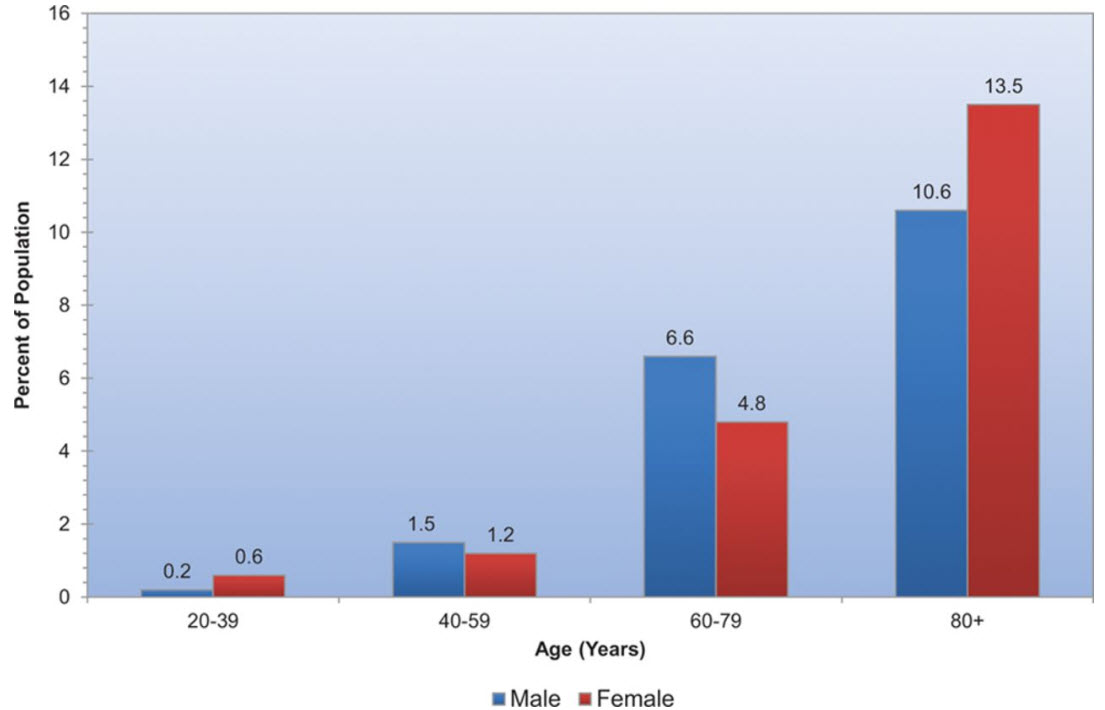

It is estimated that about 5.7 million adults in the United States have heart failure (about 2,650,000 males, and 2,650,000 females).

It is estimated that the prevalence of HF will increase 46% from 2012 to 2030, resulting in >8 million people ≥18 years of age with HF in the United States.[1]

Prevalence of heart failure by sex and age (Source: National Center for Health Statistics and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute).

Incidence

- Approximately, there are 915 000 new HF cases annually.[1]

- Data from the NHLBI’s Framingham Heart Study indicate that;[2][3]

- Heart failure (HF) incidence approaches 10 per 1,000 population after age 65.

- 75% of heart failure cases have antecedent hypertension. About 22% of male and 46% of female myocardial infarction (MI) victims will be disabled with heart failure within 6 years of the index event.

- At age 40, the lifetime risk of developing heart failure for both men and women is 1 in 5.

- At age 40, the lifetime risk of heart failure occurring without antecedent myocardial infarction is 1 in 9 for men and 1 in 6 for women.

- The lifetime risk doubles for people with blood pressure >160/90 mm Hg compared to those with blood pressure <140/90 mm Hg.

- A study conducted in Olmsted County, Minnesota, showed that the incidence of heart failure (ICD9/428) has not declined during two decades, but survival after onset has increased overall, with less improvement among women and elderly persons. [4][5]

- An increase of 26% in the number of hospitalizations due to heart failure in 2017. [6]

Age

Heart failure is the leading cause of hospitalization in people older than 65.[7] In developed countries, the mean age of patients with heart failure is 75 years old. In developing countries, two to three percent of the population suffers from heart failure, but in those 70 to 80 years old, it occurs in 20—30 percent. The incidence of heart failure approaches 10 per 1000 population after age 65 years, and approximately 80% of patients hospitalized are more than 65 years old.[8]

Gender

Men have a higher incidence of heart failure, but the overall prevalence rate is similar in both sexes, since women survive longer after the onset of heart failure.[9] Women tend to be older when diagnosed with heart failure (after menopause), they are more likely than men to have diastolic dysfunction, and seem to experience a lower overall quality of life than men after diagnosis.[9]

Race

New information suggests that elements of heart failure in African Americans and Caucasians may be different[10] and therapy for heart failure has different efficacies depending on racial, ethnic, and genetic backgrounds. Blacks have the highest risk for HF. In the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study, black men were found to have the highest risk, while white women were found to have the lowest risk.[8]

Country Specific Causes

In tropical countries, the most common cause of HF is valvular heart disease or some type of cardiomyopathy. Moreover as underdeveloped countries become more affluent, there has also been an increase in diabetes, hypertension and obesity which has resulted in heart failure.

In USA, HF is much higher in African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans and recent immigrants from the eastern bloc countries like Russia. This high prevalence in these ethnic populations has been linked to high incidence of diabetes and hypertension. In many new immigrants to the USA the high prevalence of heart failure has largely been attributed to lack of preventive health care or substandard treatment.[11]

Costs

In the United States, HF costs exceed $40 billion, taking into consideration the cost of medications, healthcare services and lack of productivity. It's noteworthy that HF is respsonsible for 1 in 9 deaths in the United States.[8]

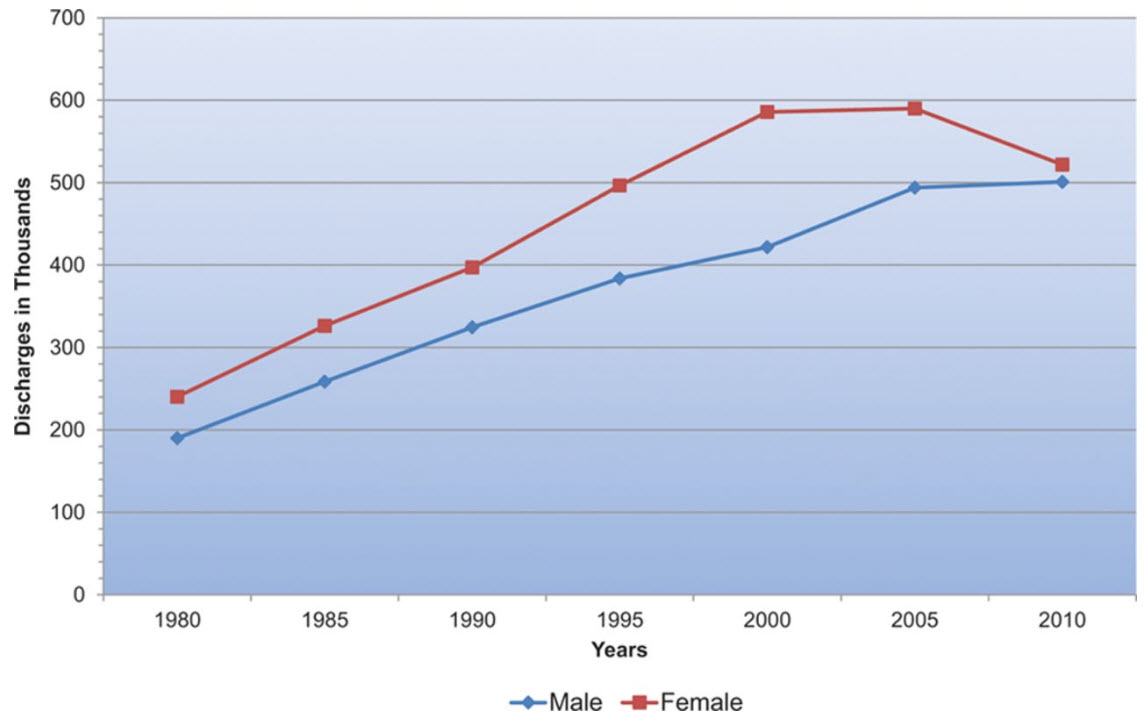

Hospital discharges for heart failure by sex which include people discharged alive, dead, and status unknown. Source: National Hospital Discharge Survey/National Center for Health Statistics and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB (2016). "Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 133 (4): e38–360. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. PMID 26673558.

- ↑ Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2008 Update, American Heart Association. Accessed on 09 March 2008

- ↑ Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Leip EP, Beiser A, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Murabito JM, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D; Lifetime Risk for Developing Congestive Heart Failure. Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2002; 106: 3068–72 PMID 12473553

- ↑ Véronique L. Roger, Susan A. Weston, Margaret M. Redfield, Jens P. Hellermann-Homan, Jill Killian, Barbara P. Yawn, Steven J. Jacobsen Trends in Heart Failure Incidence and Survival in a Community-Based Population JAMA. 2004; 292: 344-50 PMID 15265849

- ↑ Thomas S, Rich MW (2007) Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and prognosis of heart failure in the elderly. Heart Fail Clin 3 (4):381-7. DOI:10.1016/j.hfc.2007.07.004 PMID: 17905375

- ↑ Agarwal MA, Fonarow GC, Ziaeian B (2021). "National Trends in Heart Failure Hospitalizations and Readmissions From 2010 to 2017". JAMA Cardiol. 6 (8): 952–956. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.7472. PMC 7876620 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 33566058 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Krumholz HM, Chen YT, Wang Y, Vaccarino V, Radford MJ, Horwitz RI (2000). "Predictors of readmission among elderly survivors of admission with heart failure". Am. Heart J. 139 (1 Pt 1): 72–7. doi:10.1016/S0002-8703(00)90311-9. PMID 10618565.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Masoudi FA, Butler J, McBride PE; et al. (2013). "2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". J Am Coll Cardiol. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. PMID 23747642.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Strömberg A, Mårtensson J. (2003). "Gender differences in patients with heart failure". Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00002-1. PMID 14622644. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Aronow, WS (1999). "Comparison of incidence of congestive heart failure in older African-Americans, Hispanics, and Caucasians". Am J of Cardiol. 84 (5): 611–2. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00392-6. PMID 10482169. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Heart Failure Information, Retrieved on 2010-01-21.