Pre-excitation syndrome

|

Pre-excitation syndrome Microchapters |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [2] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Shivam Singla, M.D.[3]

Synonyms and keywords: Pre Excitation Syndromes; Lown-Ganong-Levine Syndrome; Pre-Excitation, Mahaim-Type; Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome

Overview

Pre-excitation syndrome is a condition in which the ventricles of heart depolarize earlier than expected via some accessory pathway conduction thus, leading to the premature contraction. Normally, atria and ventricles are interconnected with each other via AV node (atrioventricular node). But in all the pre-excitation syndromes, an accessory pathway is present that conducts impulses to ventricles besides the AV node. The accessory pathway passes the electrical impulses to the ventricles before the normal impulse of depolarization passes through the AV node. The phenomenon of depolarizing ventricles through the accessory pathway earlier than the usual depolarization is supposed to happen through the AV node is referred to as "Pre- Excitation". WPW syndrome was described in 1930 and named after John Parkinson, Paul Dudley White, and Louis Wolff. The accessory pathways are named depending upon the regions of atria and ventricles they are connecting such as Bundle of His, Mahaim fibers, and James fibers.

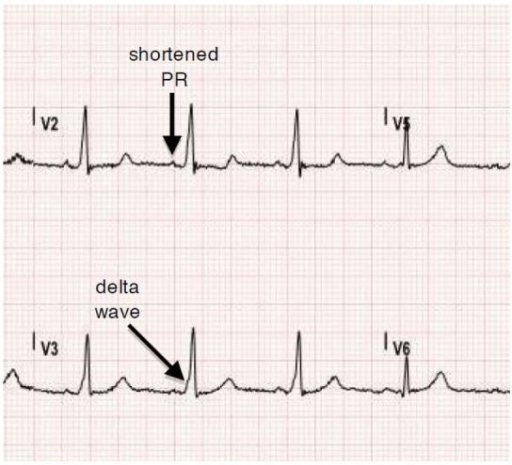

The typical ECG findings associated with WPW syndrome are shortened PR interval, widened QRS complex and Delta wave which is a slurring in the upstroke of QRS complex due to preexcitation of ventricles via the accessory pathway. ECG findings along with symptomatic tachyarrhythmias are referred to as Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Although it is more common in the adult, males have an incidence rate of 0.1-0.3 %, WPW can be considered as a congenital anomaly in some cases where it is usually present since the birth and in others, it is considered as a developmental anomaly. Studies have proven its lower prevalence in children aged between 6-13 than those in the age group of 14-15 years of age. Hemodynamically unstable patients should be managed with a direct cardioversion. For the stable patients, medical management should be tried first before going for other acceptable options of catheter ablation or surgical intervention. Although Catheter ablation has widely replaced the surgical option due to its less invasive technique and better outcomes, still in cases where catheter ablation cannot be done or doesn't prove to be effective, the surgical option is worth considering with a curative rate of nearly 100%.

Historical Perspective

- In 1915, Frank Norman Wilson became the first to describe the condition which would later be referred to as Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome.

- In 1930, WPW syndrome was first described and named after John Parkinson, Paul Dudley White, and Louis Wolff. They successfully interpreted a series of 11 healthy young patients who had repeated attacks of tachycardia in the presence of short PR interval and bundle branch block pattern on the ECG findings. They also found the association of WPW with increasing the risk of sudden cardiac death.[1]

- British physiologist "Albert Frank Stanley Kent" (1863 - 1958), first described the lateral branches of AV grove of the monkey heart, which were later named as the accessory bundle of Kent.

Classification

- Based on the conduction pathway or fiber subtype, pre-excitation syndrome may be classified into the following sub-types:[2]

| Type | Conduction pathway | QRS interval | PR interval | Delta wave |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome | Bundle of Kent | Wide/long | Usually short | Yes |

| Lown-Ganong-Levine syndrome | "James bundle" (atria to bundle of His) | Normal/Unaffected | Short | No |

| Mahaim-type | Mahaim fibers | Long | Normal | No |

- Based on their conduction properties, three types of accessory pathways are there:[3]

- Manifest Accessory Pathways: Conducts more rapidly as compared to AV nodal conduction. Delta waves are commonly seen in ECG.

- Concealed Accessory Pathways: Conducts in the retrograde direction. As its name represents, the changes in ECG are concealed and no delta waves are seen.

- Latent Accessory Pathways: These are located in the lateral part of the heart as compared to AV node. Hence, the impulses are delayed in traveling to the ventricles through the AV node which is at a much shorter distance as compared to the latent fibers located at the farther end.

Pathophysiology

Normal electrical conduction pathway of heart

- Normally, the electrical activity of the heart starts from SA node.

- The impulse generation usually happens in the right atrium near the entrance of superior vena cava and it travels from SA node to the AV node.[4]

- The AV node modulates the rate and number of impulses to be conducted to the ventricles. It also modulates the speed of transmission from atria to ventricles which represents the PR interval on ECG.

- From the AV node, an electrical impulse is transmitted to the bundle of His, to left and right branches extending to the ventricular myocardium.

Pre-excitation pathway

- WPW is another word for pre-excitation of the ventricle through the accessory pathway instead of going through the usual pathway of AV node which usually slows down the speed of conduction of impulses transmitting to ventricles.[5]

- The accessory pathway creates a channel directly to conduct the impulses to ventricles resulting in premature excitation.

- In "Type A Pre-excitation" accessory pathway lies between Left atria ventricles and in Type B pre-excitation fibers carry impulses between right atria and ventricles.[6][7]

- Basic concept of pathophysiology in pre-excitation syndrome lies in the concept of bypassing the AV node conduction and letting the impulse conduct faster through atria to ventricles via accessory pathways.

- These accessory pathways usually called Bundle of Kent in WPW syndrome, James fiber in LGL syndrome and Mahaim fibers in Mahaim type pre-excitation syndrome.

- These conducts impulses in forward (not common), backward ( around 15-20%), and in both directions (most common type) as well.

- The accessory pathways mediate the occurrence of tachyarrhythmia by forming a re-entry circuit and commonly known as AVRT.[8]

- The direct conduction of impulses from atria to ventricles can also result in the development of tachyarrhythmia's when there is a development of Atrial Fibrillation with RVR.

- WPW syndrome is a combination of WPW pattern on ECG + Paroxysmal arrhythmias.

- The accessory pathways are usually named as Bundle of Kent or AV bypass tracts.

- The accessory pathways here are named as James fibers, also known as Atrionodal fibers connecting the atrium to the distal AV node.

- These usually conduct the impulses from atria to the initial portion of the AV node.

- The accessory pathways named as Mahaim fibers connect the Atrium, AV node, or bundle of His to the Purkinje fibers or ventricular myocardium.

Differentiating Pre-excitation Syndrome from other Diseases

| Arrhythmia | Rhythm | Rate | P wave | PR Interval | QRS Complex | Response to Maneuvers | Epidemiology | Co-existing Conditions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial Fibrillation (AFib)[9][10] |

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Atrial Flutter[11] |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia (AVNRT)[12][13][14] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Multifocal Atrial Tachycardia[15][16] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Premature Atrial Contractrions (PAC)[17][18] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome[19][20] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Ventricular Fibrillation (VF)[21][22][23] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Ventricular Tachycardia[24][25] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Epidemiology and Demographics

- WPW is commonly found with an incidence of around 0.1-3.0 per thousand population.[26]

- More common in the male population as compared to females.[27]

- Familial studies are done to found its association proved that around .55% more commonly found in first degree relatives.

- More common in young and healthy individuals and as the age advances the prevalence of disease decreases because of loss of pre-excitation.

- WPW can be considered as a congenital anomaly in some cases where it is usually present since birth and in others and it is regarded as a developmental anomaly. Studies proved it's lower prevalence in children aged between 6-13 than those in the age group of 14-15 years of age.

Risk Factors

High-risk population for development of atrial fibrillation or sudden cardiac death include:

- Pilots

- Male gender

- Athletes

- Policemen

- Steelworkers

- Firemen

- Past history of syncope

- Age (peak ages for the development of atrial fibrillation include 30 years and 50 years)

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

Natural History

- There are a lot of studies being done in the past to describe the natural history or disease course of pre-excitation syndrome. But data from a recent study- "Long term natural history of patients with WPW treated with or without catheter ablation" showed promising results in explaining the reduced long-term mortality rates in WPW patients who are matched for age and gender. Also explained the lower mortality rates in catheter ablated patients as compared to non ablated ones. Although the patients can die with sudden cardiac death but the rate of this scenaio is very less and not commonly observed.[28]

Complications

- Most common complications studied in patients having accessory pathway conduction are Arrhythmias and Sudden cardiac death

- Tachyarrhythmias:

- If there is a development of atrial fibrillation or flutter then there is fast conduction across the tracts leads to an increased risk of dangerous ventricular arrhythmias.

- AV nodal blocking agents may also be the factor responsible for the increased conduction through accessory pathways causing life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias or hemodynamic instability resulting and with a worse prognosis.

- Sudden cardiac death:

- Sudden cardiac death as a complication in patients with AP conduction is more common in a young male with age less than 35, history of arrhythmias in the past, anatomical location of accessory pathway- that is the septal location of the accessory pathway, having multiple accessory pathways.

- The studies proved the risk of sudden cardiac death related to the pre-excitation syndrome is around 1.5% in childhood with the highest risk in the first two decades of life.

Prognosis

- Prognosis is usually very good till the time patient is getting managed and treated appropriately.

- Catheter ablation showed promising results in the curative treatment of patients suffering from this disorder.

- Sudden cardiac death is rarely seen in patients with this syndrome but when it happens it is most commonly related to arrhythmias.

- The most common misconception about the prognosis of WPW syndrome is related to the severity of symptoms in a patient but the most important determinant of prognosis is the dependence on the electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathways.

- The conduction through accessory pathways usually decreases with age. This is due to fibrotic changes that happen with time.

Diagnosis

WPW Syndrome

- WPW syndrome is a combination of WPW pattern on ECG + Paroxysmal arrhythmias. The accessory pathways are usually named as Bundle of Kent or AV bypass tracts.

- ECG features of WPW syndrome are

- Short PR interval <120 ms ( < .12 seconds) with Normal P wave morphology.

- Widened QRS complex ( >.12 seconds)

- Delta wave - slurring upstroke of the initial QRS complex due to the early and rapid depolarization of ventricles, the most important criteria for the diagnosis of WPW syndrome.

- Deflection of T waves opposite to the direction of QRS complexes / Secondary changes in ST-segment and T wave.

- Types of AVRT varies depending on the direction of the impulse conduction in the re-entry circuit (orthodromic or antidromic). Orthodromic AVRT means the antegrade conduction will be through the AV node and retrograde will be through the accessory pathway - presents with narrow QRS complexes on ECG. Antidromic AVRT means the antegrade conduction will be through the AP and retrograde conduction through AV node - presents with wide complex QRS complexes on ECG. SO, in short, the Orthodromic AVRT preexcitation syndrome will present with narrow complex tachycardia and Antidromic AVRT pre-excitation syndrome will present with wide complex tachycardia.

- AF with RVR can be diagnosed in patients with WPW by comparing it with the baseline ECG. Means look for comparison between pre-excited QRS complexes on the baseline ECG vs those seen during irregular tachycardia.

- Mainly categorized into 2 subtypes

- Type A - Positive delta wave

- Type B - Negative delta wave

Lown-Ganong-Levine(LGL) Syndrome

- The accessory pathways here are named as James fibers, also known as atrionodal fibers connecting the atrium to the distal AV node. These usually conduct the impulses from atria to the initial portion of the AV node.

- ECG features:

- PR interval is less than 120ms or .12 seconds with usual normal P wave morphology

- Normal QRS complex

- Absence of delta waves

- Episodic paroxysmal SVT

Mahaim-Type Pre-excitation

- The accessory pathways named as Mahaim fibers connect the Atrium, AV node, or bundle of His to the Purkinje fibers or ventricular myocardium.

- ECG findings are usually normal

History and Symptoms

- People with Pre- Excitation syndromes may be asymptomatic, however, the individuals commonly experience the following symptoms:

- Palpitations

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Fatigue

- Anxiety

- Fainting

- Difficulty breathing

Treatment

Medical Treatment

HEMODYNAMICALY UNSTABLE PATIENT -- DIRECT SYNCHRONIZED CARDIOVERSION, BIPHASIC ( INITIAL 100 J, LATER ON- 200J OR 360J).

HEMODYNAMICALLY STABLE PATIENTS -- THE FOLLOWING ALGORITHM CAN BE FOLLOWED

GENERAL PROTOCOL

- Antiarrhythmic drug

- Helps in slowing the accessory pathway conduction and thus plays a major role in the acute events.

- AV Nodal blocking agents should NOT be used

- As they aggravate WPW by increasing the conduction through the accessory pathway.

- Address the underlying cause triggering dysrhythmias which includes

IN CASE OF ACUTE AVRT/AVNRT

- Treated by blocking the AV nodal conduction

- Help in blocking the pathways responsible for causing dysrhythmias through the involvement of the AV node (AVRT/AVNRT).

- Vagal Maneuvers - Valsalva maneuver, immersing the face in cold water or ice water, carotid sinus massage

- IV Adenosine- very short half-life and commonly used in dose around 6-12 mg

- IV Verapamil- this is a calcium channel blocker and commonly used as 5-10 mg.

ATRIAL FLUTTER/FIBRILLATION

- If wide complex tachycardia is present

- Use IV Amiodarone or Procainamaide

RADIOFREQUENCY ABLATION

- This modality has replaced drug therapy and other surgical treatment options by showing promising results. Best results are studied these days when it is used in conjunction with cryoblation (commonly used for septal Accessory pathways and for accessory pathways near small coronary arteries).[26]

- This technique is used widely with best results in:

- Patients with AVRT showing symptoms of dysrhythmias

- Patients with impaired functional daily activities having no symptoms with ventricular pre-excitation

- Patients with WPW and family history of sudden cardiac death in first or second-degree relatives.

- Patients with AVRT OR A.FIB with RVR

- Patients with h/o Pre-excited A.FIB

- Patients who are not willing to undergo radiofrequency ablation can be managed on medical management with the use of Anti-arrhythmic. Though its role in the prevention of future episodes of arrhythmias is limited still this is the most commonly used modality of choice.

Class 3 Antiarrhythmics and class IC drugs are used with AV nodal blocking agents in patients with a history of atrial flutter or A.Fib. Sotalol and Flecainide would be the safe options to use in pregnancy.

Surgical management

- ENDOCARDIAL SURGICAL APPROACH

- EPICARDIAL SURGICAL APPROACH

- Due to the continuing advancement in medical science, Radiofrequency catheter ablation is widely used as a preferred treatment option.

- Role of the surgical approach nowadays is limited to:

- Patients who are undergoing cardiac surgery due to other causes.

- Patients in whom catheter ablation is tried but failed in the past.

- Patients with multiple areas or foci generating the impulses usually requires a surgical approach for best outcomes.

Prevention

- The most common preventive measures used against WPW are radiofrequency catheter ablation.

- This helps in preventing future attacks by doing the ablation of accessory pathways with a success rate of >95%.

- Although the success rate for the surgical approach is 100% still the catheter ablation is preferred as it is less invasive and associated with lower complication rates.

- Surgical success and best prognostic outcomes nowadays are only seen in patients who are having heart surgeries done for other causes such as cardiac Bypass grafting or for valvular repair.

- General measures that help in preventing the episodes like Valsalva maneuvers should be taught to the patient so that tachycardia can be relieved during an acute episode.

- Although medicines / Antiarrhythmic can help prevent recurrent episodes this is only preferred in patients who are not the candidates for catheter ablation or surgical approach.

References

- ↑ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eupc.2004.09.005

- ↑ Lowe KG, Emslie-Smith D, Ward C, Watson H (January 1975). "Classification of ventricular pre-excitation. Vectorcardiographic study". Br Heart J. 37 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1136/hrt.37.1.9. PMC 484149. PMID 1111564.

- ↑ Kuramoto K, Matsushita S (August 1972). "[Classification and interpretation of WPW syndrome]". Nippon Rinsho (in Japanese). 30 (8): 1770–8. PMID 4561817.

- ↑ "Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern - Conditions - GTR - NCBI".

- ↑ "What is the pathophysiology of Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome?".

- ↑ "American Heart Association | To be a relentless force for a world of longer, healthier lives".

- ↑ "Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) Syndrome ECG Review - Criteria and Examples | LearntheHeart.com".

- ↑ Moskowitz A, Chen KP, Cooper AZ, Chahin A, Ghassemi MM, Celi LA (October 2017). "Management of Atrial Fibrillation with Rapid Ventricular Response in the Intensive Care Unit: A Secondary Analysis of Electronic Health Record Data". Shock. 48 (4): 436–440. doi:10.1097/SHK.0000000000000869. PMC 5603354. PMID 28328711.

- ↑ Harris K, Edwards D, Mant J (2012). "How can we best detect atrial fibrillation?". J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 42 Suppl 18: 5–22. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2012.S02. PMID 22518390.

- ↑ Lankveld TA, Zeemering S, Crijns HJ, Schotten U (July 2014). "The ECG as a tool to determine atrial fibrillation complexity". Heart. 100 (14): 1077–84. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305149. PMID 24837984.

- ↑ Cosío FG (June 2017). "Atrial Flutter, Typical and Atypical: A Review". Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 6 (2): 55–62. doi:10.15420/aer.2017.5.2. PMC 5522718. PMID 28835836.

- ↑ Letsas KP, Weber R, Siklody CH, Mihas CC, Stockinger J, Blum T, Kalusche D, Arentz T (April 2010). "Electrocardiographic differentiation of common type atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia from atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia via a concealed accessory pathway". Acta Cardiol. 65 (2): 171–6. doi:10.2143/AC.65.2.2047050. PMID 20458824.

- ↑ Katritsis DG, Josephson ME (August 2016). "Classification, Electrophysiological Features and Therapy of Atrioventricular Nodal Reentrant Tachycardia". Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 5 (2): 130–5. doi:10.15420/AER.2016.18.2. PMC 5013176. PMID 27617092.

- ↑ Schernthaner C, Danmayr F, Strohmer B (2014). "Coexistence of atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia with other forms of arrhythmias". Med Princ Pract. 23 (6): 543–50. doi:10.1159/000365418. PMC 5586929. PMID 25196716.

- ↑ Goodacre S, Irons R (March 2002). "ABC of clinical electrocardiography: Atrial arrhythmias". BMJ. 324 (7337): 594–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7337.594. PMC 1122515. PMID 11884328.

- ↑ Scher DL, Arsura EL (September 1989). "Multifocal atrial tachycardia: mechanisms, clinical correlates, and treatment". Am. Heart J. 118 (3): 574–80. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(89)90275-5. PMID 2570520.

- ↑ Strasburger JF, Cheulkar B, Wichman HJ (December 2007). "Perinatal arrhythmias: diagnosis and management". Clin Perinatol. 34 (4): 627–52, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2007.10.002. PMC 3310372. PMID 18063110.

- ↑ Lin CY, Lin YJ, Chen YY, Chang SL, Lo LW, Chao TF, Chung FP, Hu YF, Chong E, Cheng HM, Tuan TC, Liao JN, Chiou CW, Huang JL, Chen SA (August 2015). "Prognostic Significance of Premature Atrial Complexes Burden in Prediction of Long-Term Outcome". J Am Heart Assoc. 4 (9): e002192. doi:10.1161/JAHA.115.002192. PMC 4599506. PMID 26316525.

- ↑ Rosner MH, Brady WJ, Kefer MP, Martin ML (November 1999). "Electrocardiography in the patient with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: diagnostic and initial therapeutic issues". Am J Emerg Med. 17 (7): 705–14. doi:10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90167-5. PMID 10597097.

- ↑ Rao AL, Salerno JC, Asif IM, Drezner JA (July 2014). "Evaluation and management of wolff-Parkinson-white in athletes". Sports Health. 6 (4): 326–32. doi:10.1177/1941738113509059. PMC 4065555. PMID 24982705.

- ↑ Adabag AS, Luepker RV, Roger VL, Gersh BJ (April 2010). "Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology and risk factors". Nat Rev Cardiol. 7 (4): 216–25. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2010.3. PMC 5014372. PMID 20142817.

- ↑ Glinge C, Sattler S, Jabbari R, Tfelt-Hansen J (September 2016). "Epidemiology and genetics of ventricular fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction". J Geriatr Cardiol. 13 (9): 789–797. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.09.006. PMC 5122505. PMID 27899944.

- ↑ Samie FH, Jalife J (May 2001). "Mechanisms underlying ventricular tachycardia and its transition to ventricular fibrillation in the structurally normal heart". Cardiovasc. Res. 50 (2): 242–50. doi:10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00289-3. PMID 11334828.

- ↑ Levis JT (2011). "ECG Diagnosis: Monomorphic Ventricular Tachycardia". Perm J. 15 (1): 65. doi:10.7812/tpp/10-130. PMC 3048638. PMID 21505622.

- ↑ Koplan BA, Stevenson WG (March 2009). "Ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death". Mayo Clin. Proc. 84 (3): 289–97. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61149-X. PMC 2664600. PMID 19252119.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Cohen MI, Triedman JK, Cannon BC, Davis AM, Drago F, Janousek J, Klein GJ, Law IH, Morady FJ, Paul T, Perry JC, Sanatani S, Tanel RE (June 2012). "PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS)". Heart Rhythm. 9 (6): 1006–24. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.050. PMID 22579340.

- ↑ http://www.cardiology.sk/casopis/606/pdf/04.pdf

- ↑ Obeyesekere MN, Leong-Sit P, Massel D, Manlucu J, Modi S, Krahn AD, Skanes AC, Yee R, Gula LJ, Klein GJ (May 2012). "Risk of arrhythmia and sudden death in patients with asymptomatic preexcitation: a meta-analysis". Circulation. 125 (19): 2308–15. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055350. PMID 22532593.