Sandbox:Mazia: Difference between revisions

Mazia Fatima (talk | contribs) |

Mazia Fatima (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 2,048: | Line 2,048: | ||

*Once diagnosed and successfully treated, patients with [disease name] are followed-up every [duration]. Follow-up testing includes [test 1], [test 2], and [test 3]. | *Once diagnosed and successfully treated, patients with [disease name] are followed-up every [duration]. Follow-up testing includes [test 1], [test 2], and [test 3]. | ||

==Clinical presentation== | |||

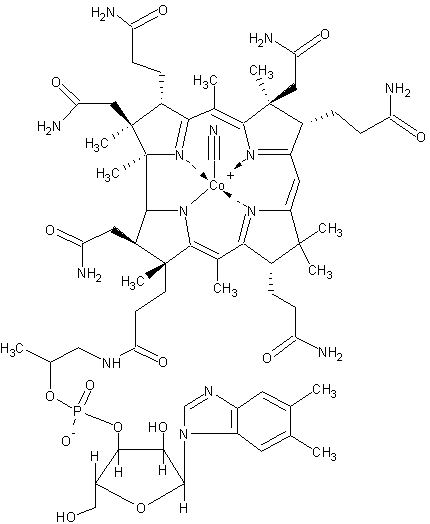

[[Image:Cobalmin.png|left|thumb|Deficiency of [[vitamin B12]] can occur in bacterial overgrowth]] | |||

Bacterial overgrowth can cause a variety of [[symptom]]s, many of which are also found in other conditions, making the [[diagnosis]] challenging at times.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Quigley/><ref name=Teo>{{cite journal | author = Teo M, Chung S, Chitti L, Tran C, Kritas S, Butler R, Cummins A | title = Small bowel bacterial overgrowth is a common cause of chronic diarrhea. | journal = J Gastroenterol Hepatol | volume = 19 | issue = 8 | pages = 904-9 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15242494}}</ref> <!-- | |||

-->Many of the symptoms are due to [[malabsorption]] of nutrients due to the effects of bacteria which either metabolize nutrients or cause inflammation of the small bowel impairing absorption. The symptoms of bacterial overgrowth include [[nausea]], [[bloating]], [[flatus]], and [[chronic]] [[diarrhea]]. Some patients may develop abdominal discomfort and lose weight. Children with bacterial overgrowth may develop [[malnutrition]] have difficulty attaining [[failure to thrive|proper growth]]. [[Steatorrhea]] is a sticky type of diarrhea, where [[lipid]]s are malabsorbed and spill into the stool.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Kirsch>{{cite journal | author = Kirsch M | title = Bacterial overgrowth. | journal = Am J Gastroenterol | volume = 85 | issue = 3 | pages = 231-7 | year = 1990 | id = PMID 2178395}}</ref><!-- | |||

--> | |||

Patients with bacterial overgrowth that is longstanding can develop complications of their illness as a result of malabsorption of nutrients. [[Anemia]] may occur from a variety of mechanisms, as many of the nutrients involved in production of [[red blood cell]]s are absorbed in the affected small bowel. [[Iron]] is absorbed in the more proximal parts of the small bowel, the [[duodenum]] and [[jejunum]], and patients with malabsorption of iron can develop a [[microcytic anemia]], with small red blood cells. [[Vitamin B12]] is absorbed in the last part of the small bowel, the [[ileum]], and patients who malabsorb vitamin B12 can develop a [[megaloblastic anemia]] with large red blood cells.<ref name=Kirsch/> | |||

==Pathophysiology== | |||

[[Image:E coli at 10000x, original.jpg|left|thumb|''E. coli'', shown in this electron micrograph, is commonly isolated in patients with bacterial overgrowth]] | |||

Certain species of bacteria are more commonly found in aspirates of the [[jejunum]] taken from patients with bacterial overgrowth. The most common isolates are ''[[Escherichia coli]]'', ''[[Streptococcus]]'', ''[[Lactobacillus]]'', ''[[Bacteroides]]'', and ''[[Enterococcus]]'' species.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Bouhnik>{{cite journal | author = Bouhnik Y, Alain S, Attar A, Flourié B, Raskine L, Sanson-Le Pors M, Rambaud J | title = Bacterial populations contaminating the upper gut in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. | journal = Am J Gastroenterol | volume = 94 | issue = 5 | pages = 1327-31 | year = 1999 | id = PMID 10235214}}</ref> <!-- | |||

--> | |||

Soon after birth, the [[gastrointestinal tract]] is colonized with bacteria, which, on the basis of models with animals raised in a germ-free environment, have beneficial effects on function of the gastrointestinal tract. There are 500-1000 different species of bacteria that reside in the bowel.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Germ>{{cite journal | author = Hao W, Lee Y | title = Microflora of the gastrointestinal tract: a review. | journal = Methods Mol Biol | volume = 268 | issue = | pages = 491-502 | year = | id = PMID 15156063}}</ref> <!-- | |||

-->However, if the flora of the small bowel is altered, inflammation or altered digestion can occur, leading to symptoms. Many patients with chronic diarrhea have bacterial overgrowth as a cause or a contributor to their symptoms.<ref name=Teo/> While the consensus definition of chronic diarrhea varies, in general it is considered to be an alteration in stool consistency or increased frequency, that occurs for over three weeks. Various mechanisms are involved in the development of diarrhea in bacterial overgrowth. First, the excessive bacterial concentrations can cause direct inflammation of the small bowel cells, leading to an ''inflammatory'' diarrhea. The malabsorption of [[lipid]]s, [[protein]]s and [[carbohydrate]]s may cause poorly digestible products to enter into the [[colon (anatomy)|colon]]. This can cause diarrhea by the [[osmosis|osmotic drive]] of these molecules, but can also stimulate the secretory mechanisms of colonic cells, leading to a ''secretory diarrhea''.<ref name=Kirsch/> | |||

==Risk factors and causes== | |||

[[Image:Ileocecal valve.jpg|thumb|left|The [[ileo-cecal valve]] prevents reflux of bacteria from the colon into the small bowel. Resection of the valve can lead to bacterial overgrowth]] | |||

Certain patients are more predisposed to the development of bacterial overgrowth because of certain risk factors. These factors can be grouped into three categories: (1) disordered [[motility]] or movement of the small bowel or anatomical changes that lead to [[stasis]], (2) disorders in the [[immune system]] and (3) conditions that cause more bacteria from the [[colon (anatomy)|colon]] to enter the [[small bowel]].<ref name=Quigley/> | |||

Problems with motility may either be diffuse, or localized to particular areas. Diseases like [[scleroderma]]<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Scleroreview>{{cite journal | author = Rose S, Young M, Reynolds J | title = Gastrointestinal manifestations of scleroderma. | journal = Gastroenterol Clin North Am | volume = 27 | issue = 3 | pages = 563-94 | year = 1998 | id = PMID 9891698}}</ref> <!-- | |||

-->and possibly [[celiac disease]]<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Tursi>{{cite journal | author = Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti G | title = High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in celiac patients with persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms after gluten withdrawal. | journal = Am J Gastroenterol | volume = 98 | issue = 4 | pages = 839-43 | year = 2003 | id = PMID 12738465}}</ref> <!-- | |||

-->cause diffuse slowing of the bowel, leading to increased bacterial concentrations. More commonly, the small bowel may have anatomical problems, such as out-pouchings known as [[diverticula]] that can cause bacteria to accumulate.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Kongara>{{cite journal | author = Kongara K, Soffer E | title = Intestinal motility in small bowel diverticulosis: a case report and review of the literature. | journal = J Clin Gastroenterol | volume = 30 | issue = 1 | pages = 84-6 | year = 2000 | id = PMID 10636218}} </ref><!-- | |||

--> After surgery involving the [[stomach]] and [[duodenum]] (most commonly with [[Billroth II]] antrectomy), a ''blind loop'' may be formed, leading to stasis of flow of intestinal contents. This can cause overgrowth, and is termed ''blind loop syndrome''.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Kim>{{cite journal | author = Isaacs P, Kim Y | title = Blind loop syndrome and small bowel bacterial contamination. | journal = Clin Gastroenterol | volume = 12 | issue = 2 | pages = 395-414 | year = 1983 | id = PMID 6347463}}</ref><!-- | |||

--> | |||

Disorders of the immune system can cause bacterial overgrowth. Chronic [[pancreatitis]], or inflammation of the [[pancreas]] can cause bacterial overgrowth through mechanisms linked to this.<!-- | |||

--><ref>{{cite journal | author = Trespi E, Ferrieri A | title = Intestinal bacterial overgrowth during chronic pancreatitis. | journal = Curr Med Res Opin | volume = 15 | issue = 1 | pages = 47-52 | year = 1999 | id = PMID 10216811}}</ref> <!-- | |||

-->The use of [[immunosuppressant]] medications to treat other conditions can cause this, as evidenced from animal models.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Marshall>{{cite journal | author = Marshall J, Christou N, Meakins J | title = Small-bowel bacterial overgrowth and systemic immunosuppression in experimental peritonitis. | journal = Surgery | volume = 104 | issue = 2 | pages = 404-11 | year = 1988 | id = PMID 3041643}}</ref> <!-- | |||

--> Other causes include inherited immunodeficiency conditions, such as [[combined variable immunodeficiency]], IgA deficiency, and [[hypogammaglobulinemia]].<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Pediatrics>{{cite journal | author = Pignata C, Budillon G, Monaco G, Nani E, Cuomo R, Parrilli G, Ciccimarra F | title = Jejunal bacterial overgrowth and intestinal permeability in children with immunodeficiency syndromes. | journal = Gut | volume = 31 | issue = 8 | pages = 879-82 | year = 1990 | id = PMID 2387510}}</ref><!-- | |||

--> | |||

Finally, abnormal connections between the [[bacteria]]-rich colon and the small bowel can increase the bacterial load in the small bowel. Patients with [[Crohn's disease]] or other diseases of the [[ileum]] may require surgery that removes the [[ileo-cecal valve]] connecting the small and large bowel; this leads to an increased reflux of bacteria into the small bowel.<!-- | |||

--><ref name-Kholoussy>{{cite journal | author = Kholoussy A, Yang Y, Bonacquisti K, Witkowski T, Takenaka K, Matsumoto T | title = The competence and bacteriologic effect of the telescoped intestinal valve after small bowel resection. | journal = Am Surg | volume = 52 | issue = 10 | pages = 555-9 | year = 1986 | id = PMID 3767143}}</ref> <!-- | |||

--> After [[bariatric surgery]] for obesity, connections between the stomach and the [[ileum]] can be formed, which may increase bacterial load in the small bowel.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=AJS>{{cite journal | author = Abell T, Minocha A | title = Gastrointestinal complications of bariatric surgery: diagnosis and therapy. | journal = Am J Med Sci | volume = 331 | issue = 4 | pages = 214-8 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16617237}}</ref> <!-- | |||

-->[[Proton pump inhibitor]] medications that decrease acid in the [[stomach]] cause bacterial overgrowth by a similar mechanism, as they prevent the anti-bacterial effects of acid in the stomach. The clinical significance of this in causing symptoms is unclear.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=PPI>{{cite journal | author = Laine L, Ahnen D, McClain C, Solcia E, Walsh J | title = Review article: potential gastrointestinal effects of long-term acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors. | journal = Aliment Pharmacol Ther | volume = 14 | issue = 6 | pages = 651-68 | year = 2000 | id = PMID 10848649}}</ref><ref name=PPI2>{{cite journal | author = Williams C, McColl K | title = Review article: proton pump inhibitors and bacterial overgrowth. | journal = Aliment Pharmacol Ther | volume = 23 | issue = 1 | pages = 3-10 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16393275}}</ref> | |||

==Diagnosis== | |||

[[Image:Agar plate with colonies.jpg|left|thumb|Aspiration of from the [[jejunum]] is the gold standard for diagnosis. A bacterial load of greater than 10<sup>5</sup> bacteria per milillitre is diagnostic for bacterial overgrowth]] | |||

The diagnosis of bacterial overgrowth can be made by physicians in various ways. [[Malabsorption]] can be detected by a test called the ''D-xylose'' test. [[Xylose]] is a sugar that does not require enzymes to be digested. The D-xylose test involves having a patient to drink a certain quantity of D-xylose, and measuring levels in the [[urine]] and [[blood]]; if there is no evidence of D-xylose in the [[urine]] and [[blood]], it suggests that the small bowel is not absorbing properly (as opposed to problems with enzymes required for digestion).<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Dxylose>{{cite journal | author = Craig R, Atkinson A | title = D-xylose testing: a review. | journal = Gastroenterology | volume = 95 | issue = 1 | pages = 223-31 | year = 1988 | id = PMID 3286361}}</ref><!-- | |||

--> | |||

The gold standard for detection of bacterial overgrowth is the aspiration of more than 10<sup>5</sup> bacteria per millilitre from the small bowel. The normal small bowel has less than 10<sup>4</sup> bacteria per millilitre.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Corazza>{{cite journal | author = Corazza G, Menozzi M, Strocchi A, Rasciti L, Vaira D, Lecchini R, Avanzini P, Chezzi C, Gasbarrini G | title = The diagnosis of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Reliability of jejunal culture and inadequacy of breath hydrogen testing. | journal = Gastroenterology | volume = 98 | issue = 2 | pages = 302-9 | year = 1990 | id = PMID 2295385}}</ref><!-- | |||

--> | |||

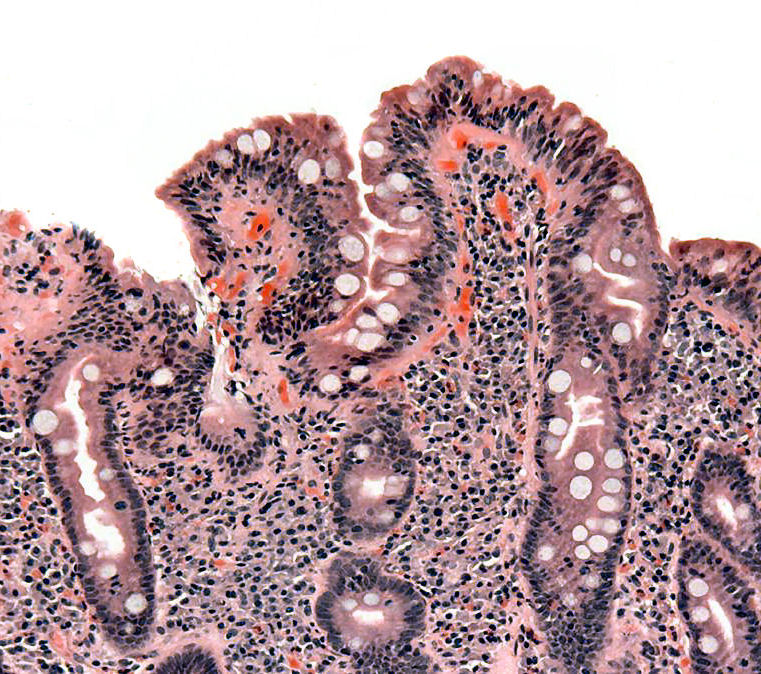

[[Image:Coeliac path.jpg|thumb|left|Biopsies of the small bowel in bacterial overgrowth can mimic [[celiac disease]], with partial [[villi|villous]] atrophy.]] | |||

Breath tests have been developed to test for bacterial overgrowth, based on bacterial metabolism of [[carbohydrates]] to [[hydrogen]], or based on the detection of by-products of digestion of carbohydrates that are not usually metabolized. The hydrogen breath test involves giving patients a load of carbohydrate (usually in the form of [[rice]]) and measuring expired hydrogen concentrations after a certain time. It compares well to jejunal aspirates in making the diagnosis of bacterial overgrowth.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Kerlin>{{cite journal | author = Kerlin P, Wong L | title = Breath hydrogen testing in bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine. | | |||

journal = Gastroenterology | volume = 95 | issue = 4 | pages = 982-8 | year = 1988 | id = PMID 3410238}}</ref> <!-- | |||

--><sup>13</sup>C and <sup>14</sup>C based tests have also been developed based on the bacterial metabolism of D-xylose. Increased bacterial concentrations are also involved in the deconjugation of bile acids. The glycocholic acid breath test involves the administration of the bile acid <sup>14</sup>C glychocholic acid, and the detection of <sup>14</sup>CO<sub>2</sub>, which would be elevated in bacterial overgrowth.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Geri>{{cite journal | author = Donald I, Kitchingmam G, Donald F, Kupfer R | title = The diagnosis of small bowel bacterial overgrowth in elderly patients. | journal = J Am Geriatr Soc | volume = 40 | issue = 7 | pages = 692-6 | year = 1992 | id = PMID 1607585}}</ref> <!-- | |||

--> | |||

Some patients with symptoms of [[bacterial overgrowth]] will undergo [[gastroscopy]], or visualization of the stomach and duodenum with an endoscopic [[camera]]. Biopsies of the small bowel in [[bacterial overgrowth]] can mimic those of [[celiac disease]], making the diagnosis more challenging. Findings include blunting of [[villi]], hyperplasia of crypts and an increased number of [[lymphocyte]]s in the [[lamina propria]].<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Toskes>{{cite journal | author = Toskes P, Giannella R, Jervis H, Rout W, Takeuchi A | title = Small intestinal mucosal injury in the experimental blind loop syndrome. Light- and electron-microscopic and histochemical studies. | journal = Gastroenterology | volume = 68 | issue = 5 Pt 1 | pages = 1193-203 | year = 1975 | id = PMID 1126607}}</ref><!-- | |||

--> | |||

However, some physicians suggest that if the suspicion of bacterial overgrowth is high enough, the best diagnostic test is a trial of treatment. If the symptoms improve, an empiric diagnosis of bacterial overgrowth can be made.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Singh>{{cite journal | author = Singh VV, Toskes PP | title = Small Bowel Bacterial Overgrowth: Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment. | journal = Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol | volume = 7 | issue = 1 | pages = 19-28 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 14723835}}</ref> | |||

==Treatment== | |||

Bacterial overgrowth is usually treated with a course of antibiotics. A variety of antibiotics, including [[neomycin]], [[rifaximin]], [[amoxicillin-clavulanate]], [[fluoroquinolone]] antibiotics and [[tetracycline]] have been used; however, the best evidence is for the use of [[norfloxacin]] and [[amoxicillin-clavulanate]].<!-- | |||

--><ref name=RCT>{{cite journal | author = Attar A, Flourié B, Rambaud J, Franchisseur C, Ruszniewski P, Bouhnik Y | title = Antibiotic efficacy in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-related chronic diarrhea: a crossover, randomized trial. | journal = Gastroenterology | volume = 117 | issue = 4 | pages = 794-7 | year = 1999 | id = PMID 10500060}}</ref> | |||

A course of one week of antibiotics is usually sufficient to treat the condition. However, if the condition recurs, antibiotics can be given in a cyclical fashion in order to prevent tolerance. For example, antibiotics may be given for a week, followed by three weeks off antibiotics, followed by another week of treatment. Alternatively, the choice of antibiotic used can be cycled.<ref name=Singh/> | |||

The condition that predisposed the patient to bacterial overgrowth should also be treated. For example, if the bacterial overgrowth is caused by [[chronic pancreatitis]], the patient should be treated with coated pancreatic [[enzyme]] supplements. | |||

[[Probiotic]]s are bacterial preparations that alter the bacterial flora in the bowel to cause a beneficial effect. Their role in bacterial overgrowth is somewhat uncertain.<ref name=Quigley/> | |||

==Overveiw== | |||

'''Small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome''' ('''SBBOS'''), or '''small intestinal bacterial overgrowth''' ('''SIBO'''), also termed '''bacterial overgrowth'''; is a disorder of excessive bacterial growth in the [[small intestine]]. Unlike the [[colon (anatomy)|colon]] (or large bowel), which is rich with [[bacteria]], the small bowel usually has less than 10<sup>4</sup> organisms per millilitre.<!-- | |||

--><ref name=Quigley>{{cite journal | author = Quigley E, Quera R | title = Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: roles of antibiotics, prebiotics, and probiotics. | journal = Gastroenterology | volume = 130 | issue = 2 Suppl 1 | pages = S78-90 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16473077}}</ref> <!-- | |||

-->Patients with bacterial overgrowth typically develop symptoms including [[nausea]], [[bloating]], [[vomiting]] and [[diarrhea]], which is caused by a number of mechanisms. The [[diagnosis]] of bacterial overgrowth is made by a number of techniques, with the [[gold standard (test)|gold standard]] diagnosis being an [[Needle aspiration biopsy|aspirate]] from the [[jejunum]] that grows in excess of 10<sup>5</sup> [[bacteria]] per millilitre. [[Risk factor]]s for the development of bacterial overgrowth include the use of medications including [[proton pump inhibitors]], [[anatomy|anatomical]] disturbances in the bowel, including [[fistula]]e, [[diverticula]] and blind loops created after surgery, and resection of the [[ileo-cecal valve]]. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome is treated with [[antibiotic]]s, which may be given in a cyclic fashion to prevent tolerance to the antibiotics. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{Reflist|2}} | {{Reflist|2}} | ||

Revision as of 19:06, 29 January 2018

Historical Perspective

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) was first discovered by Barber and Hummel in 1939.

- In 2000, Pimentel et all at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center were first identified that SIBO was present in 78% of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and that treatment with antibiotics improved symptoms.

- In May 2015, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved rifaximin to treat SIBO.

Classification

- There is no established system for the classification of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth(SIBO).

Pathophysiology

- The pathogenesis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is characterized by an increased microbial load in the small intestine.

- A healthy individual has less than 103 organisms/mL in the upper small intestine, and the majority of these organisms are gram-positive bacteria.

- Body's homeostatic mechanisms protect against excessive small intestinal colonization by bacteria include :

- Gastric acid and bile eradicate micro-organisms before they leave the stomach

- Migrating motor complex clears the excess unwanted bacteria of upper intestine

- Intestinal mucosa serves as a protective layer for the gut wall.

- Normal intestinal flora (eg, Lactobacillus) maintains a low pH that prevents bacterial overgrowth.

- Physical barrier of the ileocecal valve that prevents retrograde translocation of bacteria from colon to the small intestine.

- Disruption of these protective homeostatic mechanisms can increase the risk of SIBO.

- Bacterial colonization causes an inflammatory response in the intestinal mucosa.

- Damage to the intestinal mucosa leads to malabsorption of bile acids, carbohydrates, proteins and vitamins resulting in symptoms of diarrhea and weightloss.

- On gross pathology, mucosal edema, loss of normal vascular pattern, patchy erythema, friability and ulceration of the small intestinal wall is associated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

- On microscopic histopathological analysis small intestine and colon is normal in most patients with SIBO. Findings include:

- Blunting of the intestinal villi

- Thinning of the mucosa and crypts

- Increased intraepithelial lymphocytes

Causes

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) may be caused by disruption of the protective homeostatic mechanisms that control enteric bacteria population.

- Causes of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) include:

- Irregular small intestinal motility

- Diabetic autonomic neuropathy

- Scleroderma

- Pseudo-obstruction

- Amyloidosis

- Neurological diseases (eg, myotonic dystrophy, Parkinson disease)

- Radiation enteritis

- Crohn disease

- Hypothyroidism

- Blind pouches in the gastrointestinal tract

- Side-to-side or end-to-side anastomoses

- Duodenal or jejunal diverticula

- Segmental dilatation of the ileum

- Blind loop syndrome

- Biliopancreatic diversion

- Chagasic megacolon

- Fistula

- Gastrocolic fistulae

- Jejunal-colic fistulae

- Partial Obstruction

- Strictures

- Adhesions

- Abdominal masses

- Leiomyosarcoma

- Decreased gastric acid secretion

- Achlorhydria

- Vagotomy

- Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy

- Irregular small intestinal motility

Differentiating [disease name] from other Diseases

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) must be differentiated from other diseases that cause chronic diarrhea.

The following table outlines the major differential diagnoses of chronic diarrhea.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30]

Abbreviations: GI: Gastrointestinal, CBC: Complete blood count, WBC: White blood cell, RBC: Red blood cell, Plt: Platelet, Hgb: Hemoglobin, ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP: C–reactive protein, IgE: Immunoglobulin E, IgA: Immunoglobulin A, ETEC: Escherichia coli enteritis, EPEC: Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, EIEC: Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli, EHEC: Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, EAEC: Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli, Nl: Normal, ASCA: Anti saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies, ANCA: Anti–neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid, CFTR: Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, SLC10A2: Solute carrier family 10 member 2, SeHCAT: Selenium homocholic acid taurine or tauroselcholic acid, IEL: Intraepithelial lymphocytes, MRCP: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, ANA: Antinuclear antibodies, AMA: Anti-mitochondrial antibody, LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase, CPK: Creatine phosphokinase, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction, ELISA: Enzyme–linked immunosorbent assay, LT: Heat–labile enterotoxin, ST: Heat–stable enterotoxin, RT-PCR: Reverse–transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, CD4: Cluster of differentiation 4, HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, RUQ: Right-upper quadrant, VIP: Vasoactive intestinal peptide, GI: Gastrointestinal, FAP: Familial adenomatous polyposis, HNPCC: Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, MTP: Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein, Scl‑70: Anti–topoisomerase I, TSH: Thyroid-stimulating hormone, T4: Thyroxine, T3: Triiodothyronine, DTR: Deep tendon reflex, RNA: Ribonucleic acid

| Cause | Clinical manifestation | Lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | GI signs | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | ||||||||||||||||||

| Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Crohn's disease | – | + | + | + | + | ± | + | + |

|

+ | + | – | Nl | – | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

|

|

|

| |

| Ulcerative colitis | – | + | + | + | + | ± | + | + | + | + | – | Nl | – | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

|

|

| |||

| Celiac disease | – | + | ± | – | ± | – | + | + |

|

– | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| |||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Cystic fibrosis | – | + | – | – | + | ± | + | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Chronic pancreatitis | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|||||

| Bile acid malabsorption | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Microscopic colitis | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Infective colitis | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

|

+ | + | + | Nl |

|

↑ | ↓ | ↑ | |||||

| Ischemic colitis | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

|

+ | + | – | Nl | – | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

|

|

| ||

| Lactose intolerance | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | – | + | ± | – | ± | – | ± | – | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

| |||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Whipple's disease | – | + | + | – | + | ± | + | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

↓ | ↓ | ↓/↑ |

|

| ||||

| Tropical sprue | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + |

|

+ | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

| ||||

| Small bowel bacterial overgrowth | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Salmonellosis | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | ↑ | ||||||

| Escherichia coli enteritis | EPEC | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | – | – |

| |

| EAEC | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | ↓ | ↓ | – |

|

|||

| Aeromonas | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl | – |

|

| ||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Mycobacterium avium complex | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | Nl | – | ↓ | ↓ | Nl |

|

|||||

| CMV colitis | + | + | – | + | – | ± | + | – |

|

+ | + | – | Nl |

|

↓ | Nl | Nl |

|

| |||

| HIV | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | Nl | – | ↓ | ↓ | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Entamoeba histolytica | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | Nl | – | ↑ | Nl | Nl | – |

|

| |||

| Giardia | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl | – |

| ||||

| Cryptosporidium | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Microsporidia | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

| ||||

| Isospora | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Nl |

|

↑ | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Carcinoid tumor | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | ↓ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| VIPoma | + | + | + | – | + | – | + | + |

|

– | – | – | ↓ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| ||

| Zollinger–Ellison syndrome | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | ↓ | – | Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||

| Somatostatinoma | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | ↓ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Lymphoma | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | Nl | – | Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||

| Colorectal cancer | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | + |

|

– | + | – | Nl | – | Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| |||

| Medications | + | + | + | – | ± | ± | + | + | – | – | – | ↑/↓ | – | ↑ | Nl | Nl |

|

– |

| |||

| Factitious diarrhea | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | ↑/↓ | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

| |||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Heavy metal ingestion | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

| ||||

| Organophosphate poisoning | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

|

| ||

| Opium withdrawal | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | – |

|

– | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

| ||||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Short bowel syndrome | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | ↑ |

|

|

|

| ||

| Radiation enteritis | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Dumping syndrome | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | + |

|

– | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

| |||

| Cause | Duration | Diarrhea | Fever | Abdominal pain | Weight loss | GI signs | Stool exam | CBC | Other lab findings | Extra intestinal findings | Cause/Pathogenesis | Gold standard diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Acute | Chronic | Watery | Bloody | Fatty | WBC | RBC | Ova/Parasite | Osmotic gap | Other | WBC | Hgb | Plt | ||||||||||

| Abetalipoproteinemia | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl | – | Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

| |||

| Hyperthyroidism | – | + | + | – | – | ± | + | + | – | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | Nl | Nl |

|

|

|||

| Diabetic neuropathy | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||

| Systemic sclerosis | – | + | + | ± | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | Nl |

|

Nl | ↓ | Nl |

|

| ||||

Epidemiology and Demographics

- The prevalence of SIBO is unknown.

Age

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is more commonly observed among elderly patients.

Gender

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) affects men and women equally.

Race

- There is no racial predilection for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Risk Factors

- Common risk factors in the development of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) are :

- Intestinal tract surgery

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Liver cirrhosis

- Celiac disease

- Immune deficiency (eg, AIDS, IGA deficiency, severe malnutrition)

- Short bowel syndrome

- End-stage renal disease

- Gastrojejunal anastomosis

- Antral resection

- Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

- Early clinical features include bloating, flatulence, abdominal pain.

- If left untreated, patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) may progress to develop diarrhea, dyspepsia and weight loss.

- Common complications of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) include:

- Iron deficiency resulting in microcytic anemia

- Vitamin B-12/ folate deficiency resulting in macrocytic anemia

- Vitamin B-12 deficiency associated polyneuropathy

- Steatorrhea

- Hypocalcemia

- Vitamin A deficiency resulting in night blindness

- Selenium deficiency causing dermatitis

- Rosacea

- Cachexia as a result of protein-energy malnutrition

- Prognosis is generally good and associated with frequent relapses and symptom-free periods.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Criteria

- The diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is made when at least one of the following diagnostic criteria are met:

- A positive carbohydrate breath test

- Bacterial concentration of >103 units/mL in a jejunal aspirate culture

Symptoms

- Symptoms of small intestinal bacterial overdose (SIBO) may include the following:

- Bloating

- Flatulence

- Abdominal discomfort

- Chronic watery diarrhea

- Weight loss

Physical Examination

- Patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) usually appear normal.

- Physical examination may be remarkable for:

- Distended abdomen with positive succussion splash as a result of distended bowel loops

- Peripheral edema due to malabsorption

Laboratory Findings

- A positive carbohydrate breath test is diagnostic of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

- An elevated concentration of bacterial colony forming units >103/mL in jejunal aspirate culture is diagnostic of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

- Other laboratory findings consistent with the diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) include

- Macrocytic anemia

- B12 deficiency

- Presence of fecal fat on stool examination.

- Low levels of thiamine and niacin

- Elevated serum folate and vitamin K levels

Imaging Findings

- In CT abdomen/MRI may demonstrate associated strictures, malrotation, fistulae.

Other Diagnostic Studies

Breath Tests

- Small intestinal bacterial obstruction(SIBO) may also be diagnosed using breath tests.

- Breath tests have the advantage of being easy to perform, noninvasive and inexpensive. Breath tests are based on the principle that carbohydrates are metabolized by bacteria in the gut to produce hydrogen or methane that is absorbed and excreted in breath.

- The findings on carbohydrate breath test diagnostic of small intestinal bacterial obstruction(SIBO) include:

- An increase in hydrogen by ≥20 ppm above baseline within 90 minutes.

- A methane level ≥10 ppm regardless of the time during the breath test.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- The mainstay of therapy for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth(SIBO) is antibiotic therapy.

- Antibiotics acts by eliminating the bacterial overgrowth.

- Rifaximin is the antibiotic of choice for the treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth(SIBO).

- Preferred regimen: Rifaximin 550 mg PO 8h for 14 days.

- Response to [medical therapy 1] can be monitored with [test/physical finding/imaging] every [frequency/duration].

Surgery

- Surgery is the mainstay of therapy for [disease name].

- [Surgical procedure] in conjunction with [chemotherapy/radiation] is the most common approach to the treatment of [disease name].

- [Surgical procedure] can only be performed for patients with [disease stage] [disease name].

Prevention

- There are no primary preventive measures available for [disease name].

- Effective measures for the primary prevention of [disease name] include [measure1], [measure2], and [measure3].

- Once diagnosed and successfully treated, patients with [disease name] are followed-up every [duration]. Follow-up testing includes [test 1], [test 2], and [test 3].

Clinical presentation

Bacterial overgrowth can cause a variety of symptoms, many of which are also found in other conditions, making the diagnosis challenging at times.[31][32] Many of the symptoms are due to malabsorption of nutrients due to the effects of bacteria which either metabolize nutrients or cause inflammation of the small bowel impairing absorption. The symptoms of bacterial overgrowth include nausea, bloating, flatus, and chronic diarrhea. Some patients may develop abdominal discomfort and lose weight. Children with bacterial overgrowth may develop malnutrition have difficulty attaining proper growth. Steatorrhea is a sticky type of diarrhea, where lipids are malabsorbed and spill into the stool.[33]

Patients with bacterial overgrowth that is longstanding can develop complications of their illness as a result of malabsorption of nutrients. Anemia may occur from a variety of mechanisms, as many of the nutrients involved in production of red blood cells are absorbed in the affected small bowel. Iron is absorbed in the more proximal parts of the small bowel, the duodenum and jejunum, and patients with malabsorption of iron can develop a microcytic anemia, with small red blood cells. Vitamin B12 is absorbed in the last part of the small bowel, the ileum, and patients who malabsorb vitamin B12 can develop a megaloblastic anemia with large red blood cells.[33]

Pathophysiology

Certain species of bacteria are more commonly found in aspirates of the jejunum taken from patients with bacterial overgrowth. The most common isolates are Escherichia coli, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, and Enterococcus species.[34]

Soon after birth, the gastrointestinal tract is colonized with bacteria, which, on the basis of models with animals raised in a germ-free environment, have beneficial effects on function of the gastrointestinal tract. There are 500-1000 different species of bacteria that reside in the bowel.[35] However, if the flora of the small bowel is altered, inflammation or altered digestion can occur, leading to symptoms. Many patients with chronic diarrhea have bacterial overgrowth as a cause or a contributor to their symptoms.[32] While the consensus definition of chronic diarrhea varies, in general it is considered to be an alteration in stool consistency or increased frequency, that occurs for over three weeks. Various mechanisms are involved in the development of diarrhea in bacterial overgrowth. First, the excessive bacterial concentrations can cause direct inflammation of the small bowel cells, leading to an inflammatory diarrhea. The malabsorption of lipids, proteins and carbohydrates may cause poorly digestible products to enter into the colon. This can cause diarrhea by the osmotic drive of these molecules, but can also stimulate the secretory mechanisms of colonic cells, leading to a secretory diarrhea.[33]

Risk factors and causes

Certain patients are more predisposed to the development of bacterial overgrowth because of certain risk factors. These factors can be grouped into three categories: (1) disordered motility or movement of the small bowel or anatomical changes that lead to stasis, (2) disorders in the immune system and (3) conditions that cause more bacteria from the colon to enter the small bowel.[31]

Problems with motility may either be diffuse, or localized to particular areas. Diseases like scleroderma[36] and possibly celiac disease[37] cause diffuse slowing of the bowel, leading to increased bacterial concentrations. More commonly, the small bowel may have anatomical problems, such as out-pouchings known as diverticula that can cause bacteria to accumulate.[38] After surgery involving the stomach and duodenum (most commonly with Billroth II antrectomy), a blind loop may be formed, leading to stasis of flow of intestinal contents. This can cause overgrowth, and is termed blind loop syndrome.[39]

Disorders of the immune system can cause bacterial overgrowth. Chronic pancreatitis, or inflammation of the pancreas can cause bacterial overgrowth through mechanisms linked to this.[40] The use of immunosuppressant medications to treat other conditions can cause this, as evidenced from animal models.[41] Other causes include inherited immunodeficiency conditions, such as combined variable immunodeficiency, IgA deficiency, and hypogammaglobulinemia.[42]

Finally, abnormal connections between the bacteria-rich colon and the small bowel can increase the bacterial load in the small bowel. Patients with Crohn's disease or other diseases of the ileum may require surgery that removes the ileo-cecal valve connecting the small and large bowel; this leads to an increased reflux of bacteria into the small bowel. After bariatric surgery for obesity, connections between the stomach and the ileum can be formed, which may increase bacterial load in the small bowel.[43] Proton pump inhibitor medications that decrease acid in the stomach cause bacterial overgrowth by a similar mechanism, as they prevent the anti-bacterial effects of acid in the stomach. The clinical significance of this in causing symptoms is unclear.[44][45]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of bacterial overgrowth can be made by physicians in various ways. Malabsorption can be detected by a test called the D-xylose test. Xylose is a sugar that does not require enzymes to be digested. The D-xylose test involves having a patient to drink a certain quantity of D-xylose, and measuring levels in the urine and blood; if there is no evidence of D-xylose in the urine and blood, it suggests that the small bowel is not absorbing properly (as opposed to problems with enzymes required for digestion).[46]

The gold standard for detection of bacterial overgrowth is the aspiration of more than 105 bacteria per millilitre from the small bowel. The normal small bowel has less than 104 bacteria per millilitre.[47]

Breath tests have been developed to test for bacterial overgrowth, based on bacterial metabolism of carbohydrates to hydrogen, or based on the detection of by-products of digestion of carbohydrates that are not usually metabolized. The hydrogen breath test involves giving patients a load of carbohydrate (usually in the form of rice) and measuring expired hydrogen concentrations after a certain time. It compares well to jejunal aspirates in making the diagnosis of bacterial overgrowth.[48] 13C and 14C based tests have also been developed based on the bacterial metabolism of D-xylose. Increased bacterial concentrations are also involved in the deconjugation of bile acids. The glycocholic acid breath test involves the administration of the bile acid 14C glychocholic acid, and the detection of 14CO2, which would be elevated in bacterial overgrowth.[49]

Some patients with symptoms of bacterial overgrowth will undergo gastroscopy, or visualization of the stomach and duodenum with an endoscopic camera. Biopsies of the small bowel in bacterial overgrowth can mimic those of celiac disease, making the diagnosis more challenging. Findings include blunting of villi, hyperplasia of crypts and an increased number of lymphocytes in the lamina propria.[50]

However, some physicians suggest that if the suspicion of bacterial overgrowth is high enough, the best diagnostic test is a trial of treatment. If the symptoms improve, an empiric diagnosis of bacterial overgrowth can be made.[51]

Treatment

Bacterial overgrowth is usually treated with a course of antibiotics. A variety of antibiotics, including neomycin, rifaximin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, fluoroquinolone antibiotics and tetracycline have been used; however, the best evidence is for the use of norfloxacin and amoxicillin-clavulanate.[52]

A course of one week of antibiotics is usually sufficient to treat the condition. However, if the condition recurs, antibiotics can be given in a cyclical fashion in order to prevent tolerance. For example, antibiotics may be given for a week, followed by three weeks off antibiotics, followed by another week of treatment. Alternatively, the choice of antibiotic used can be cycled.[51]

The condition that predisposed the patient to bacterial overgrowth should also be treated. For example, if the bacterial overgrowth is caused by chronic pancreatitis, the patient should be treated with coated pancreatic enzyme supplements.

Probiotics are bacterial preparations that alter the bacterial flora in the bowel to cause a beneficial effect. Their role in bacterial overgrowth is somewhat uncertain.[31]

Overveiw

Small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome (SBBOS), or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), also termed bacterial overgrowth; is a disorder of excessive bacterial growth in the small intestine. Unlike the colon (or large bowel), which is rich with bacteria, the small bowel usually has less than 104 organisms per millilitre.[31] Patients with bacterial overgrowth typically develop symptoms including nausea, bloating, vomiting and diarrhea, which is caused by a number of mechanisms. The diagnosis of bacterial overgrowth is made by a number of techniques, with the gold standard diagnosis being an aspirate from the jejunum that grows in excess of 105 bacteria per millilitre. Risk factors for the development of bacterial overgrowth include the use of medications including proton pump inhibitors, anatomical disturbances in the bowel, including fistulae, diverticula and blind loops created after surgery, and resection of the ileo-cecal valve. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome is treated with antibiotics, which may be given in a cyclic fashion to prevent tolerance to the antibiotics.

References

- ↑ Casburn-Jones, Anna C; Farthing, Michael Jg (2004). "Traveler's diarrhea". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 19 (6): 610–618. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03287.x. ISSN 0815-9319.

- ↑ Kamat, Deepak; Mathur, Ambika (2006). "Prevention and Management of Travelers' Diarrhea". Disease-a-Month. 52 (7): 289–302. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2006.08.003. ISSN 0011-5029.

- ↑ Pfeiffer, Margaret L.; DuPont, Herbert L.; Ochoa, Theresa J. (2012). "The patient presenting with acute dysentery – A systematic review". Journal of Infection. 64 (4): 374–386. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2012.01.006. ISSN 0163-4453.

- ↑ Barr W, Smith A (2014). "Acute diarrhea". Am Fam Physician. 89 (3): 180–9. PMID 24506120.

- ↑ Amil Dias J (2017). "Celiac Disease: What Do We Know in 2017?". GE Port J Gastroenterol. 24 (6): 275–278. doi:10.1159/000479881. PMID 29255768.

- ↑ Kotloff KL, Riddle MS, Platts-Mills JA, Pavlinac P, Zaidi A (2017). "Shigellosis". Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33296-8. PMID 29254859. Vancouver style error: initials (help)

- ↑ Yamamoto-Furusho, J.K.; Bosques-Padilla, F.; de-Paula, J.; Galiano, M.T.; Ibañez, P.; Juliao, F.; Kotze, P.G.; Rocha, J.L.; Steinwurz, F.; Veitia, G.; Zaltman, C. (2017). "Diagnóstico y tratamiento de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal: Primer Consenso Latinoamericano de la Pan American Crohn's and Colitis Organisation". Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 82 (1): 46–84. doi:10.1016/j.rgmx.2016.07.003. ISSN 0375-0906.

- ↑ Borbély, Yves M; Osterwalder, Alice; Kröll, Dino; Nett, Philipp C; Inglin, Roman A (2017). "Diarrhea after bariatric procedures: Diagnosis and therapy". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 23 (26): 4689. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i26.4689. ISSN 1007-9327.

- ↑ Crawford, Sue E.; Ramani, Sasirekha; Tate, Jacqueline E.; Parashar, Umesh D.; Svensson, Lennart; Hagbom, Marie; Franco, Manuel A.; Greenberg, Harry B.; O'Ryan, Miguel; Kang, Gagandeep; Desselberger, Ulrich; Estes, Mary K. (2017). "Rotavirus infection". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 3: 17083. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.83. ISSN 2056-676X.

- ↑ Kist M (2000). "[Chronic diarrhea: value of microbiology in diagnosis]". Praxis (Bern 1994) (in German). 89 (39): 1559–65. PMID 11068510.

- ↑ Guerrant RL, Shields DS, Thorson SM, Schorling JB, Gröschel DH (1985). "Evaluation and diagnosis of acute infectious diarrhea". Am. J. Med. 78 (6B): 91–8. PMID 4014291.

- ↑ López-Vélez R, Turrientes MC, Garrón C, Montilla P, Navajas R, Fenoy S, del Aguila C (1999). "Microsporidiosis in travelers with diarrhea from the tropics". J Travel Med. 6 (4): 223–7. PMID 10575169.

- ↑ Wahnschaffe, Ulrich; Ignatius, Ralf; Loddenkemper, Christoph; Liesenfeld, Oliver; Muehlen, Marion; Jelinek, Thomas; Burchard, Gerd Dieter; Weinke, Thomas; Harms, Gundel; Stein, Harald; Zeitz, Martin; Ullrich, Reiner; Schneider, Thomas (2009). "Diagnostic value of endoscopy for the diagnosis of giardiasis and other intestinal diseases in patients with persistent diarrhea from tropical or subtropical areas". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 42 (3): 391–396. doi:10.1080/00365520600881193. ISSN 0036-5521.

- ↑ Mena Bares LM, Carmona Asenjo E, García Sánchez MV, Moreno Ortega E, Maza Muret FR, Guiote Moreno MV, Santos Bueno AM, Iglesias Flores E, Benítez Cantero JM, Vallejo Casas JA (2017). "75SeHCAT scan in bile acid malabsorption in chronic diarrhoea". Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 36 (1): 37–47. doi:10.1016/j.remn.2016.08.005. PMID 27765536.

- ↑ Gibson RJ, Stringer AM (2009). "Chemotherapy-induced diarrhoea". Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 3 (1): 31–5. doi:10.1097/SPC.0b013e32832531bb. PMID 19365159.

- ↑ Abraham BP, Sellin JH (2012). "Drug-induced, factitious, & idiopathic diarrhoea". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 26 (5): 633–48. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2012.11.007. PMID 23384808.

- ↑ Reintam Blaser A, Deane AM, Fruhwald S (2015). "Diarrhoea in the critically ill". Curr Opin Crit Care. 21 (2): 142–53. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000188. PMID 25692805.

- ↑ McMahan ZH, DuPont HL (2007). "Review article: the history of acute infectious diarrhoea management--from poorly focused empiricism to fluid therapy and modern pharmacotherapy". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 25 (7): 759–69. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03261.x. PMID 17373914.

- ↑ Schiller LR (2012). "Definitions, pathophysiology, and evaluation of chronic diarrhoea". Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 26 (5): 551–62. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2012.11.011. PMID 23384801.

- ↑ Giannella RA (1986). "Chronic diarrhea in travelers: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations". Rev. Infect. Dis. 8 Suppl 2: S223–6. PMID 3523719.

- ↑ Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR; et al. (2005). "Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology". Can J Gastroenterol. 19 Suppl A: 5A–36A. PMID 16151544.

- ↑ Sauter GH, Moussavian AC, Meyer G, Steitz HO, Parhofer KG, Jüngst D (2002). "Bowel habits and bile acid malabsorption in the months after cholecystectomy". Am J Gastroenterol. 97 (7): 1732–5. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05779.x. PMID 12135027.

- ↑ Maiuri L, Raia V, Potter J, Swallow D, Ho MW, Fiocca R; et al. (1991). "Mosaic pattern of lactase expression by villous enterocytes in human adult-type hypolactasia". Gastroenterology. 100 (2): 359–69. PMID 1702075.

- ↑ RUBIN CE, BRANDBORG LL, PHELPS PC, TAYLOR HC (1960). "Studies of celiac disease. I. The apparent identical and specific nature of the duodenal and proximal jejunal lesion in celiac disease and idiopathic sprue". Gastroenterology. 38: 28–49. PMID 14439871.

- ↑ Konvolinka CW (1994). "Acute diverticulitis under age forty". Am J Surg. 167 (6): 562–5. PMID 8209928.

- ↑ Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF (2006). "The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications". Gut. 55 (6): 749–53. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.082909. PMC 1856208. PMID 16698746.

- ↑ Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA (2003). "Amebiasis". N Engl J Med. 348 (16): 1565–73. doi:10.1056/NEJMra022710. PMID 12700377.

- ↑ Hertzler SR, Savaiano DA (1996). "Colonic adaptation to daily lactose feeding in lactose maldigesters reduces lactose intolerance". Am J Clin Nutr. 64 (2): 232–6. PMID 8694025.

- ↑ Briet F, Pochart P, Marteau P, Flourie B, Arrigoni E, Rambaud JC (1997). "Improved clinical tolerance to chronic lactose ingestion in subjects with lactose intolerance: a placebo effect?". Gut. 41 (5): 632–5. PMC 1891556. PMID 9414969.

- ↑ BLACK-SCHAFFER B (1949). "The tinctoral demonstration of a glycoprotein in Whipple's disease". Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 72 (1): 225–7. PMID 15391722.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Quigley E, Quera R (2006). "Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: roles of antibiotics, prebiotics, and probiotics". Gastroenterology. 130 (2 Suppl 1): S78–90. PMID 16473077.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Teo M, Chung S, Chitti L, Tran C, Kritas S, Butler R, Cummins A (2004). "Small bowel bacterial overgrowth is a common cause of chronic diarrhea". J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 19 (8): 904–9. PMID 15242494.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Kirsch M (1990). "Bacterial overgrowth". Am J Gastroenterol. 85 (3): 231–7. PMID 2178395.

- ↑ Bouhnik Y, Alain S, Attar A, Flourié B, Raskine L, Sanson-Le Pors M, Rambaud J (1999). "Bacterial populations contaminating the upper gut in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome". Am J Gastroenterol. 94 (5): 1327–31. PMID 10235214.

- ↑ Hao W, Lee Y. "Microflora of the gastrointestinal tract: a review". Methods Mol Biol. 268: 491–502. PMID 15156063.

- ↑ Rose S, Young M, Reynolds J (1998). "Gastrointestinal manifestations of scleroderma". Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 27 (3): 563–94. PMID 9891698.

- ↑ Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti G (2003). "High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in celiac patients with persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms after gluten withdrawal". Am J Gastroenterol. 98 (4): 839–43. PMID 12738465.

- ↑ Kongara K, Soffer E (2000). "Intestinal motility in small bowel diverticulosis: a case report and review of the literature". J Clin Gastroenterol. 30 (1): 84–6. PMID 10636218.

- ↑ Isaacs P, Kim Y (1983). "Blind loop syndrome and small bowel bacterial contamination". Clin Gastroenterol. 12 (2): 395–414. PMID 6347463.

- ↑ Trespi E, Ferrieri A (1999). "Intestinal bacterial overgrowth during chronic pancreatitis". Curr Med Res Opin. 15 (1): 47–52. PMID 10216811.

- ↑ Marshall J, Christou N, Meakins J (1988). "Small-bowel bacterial overgrowth and systemic immunosuppression in experimental peritonitis". Surgery. 104 (2): 404–11. PMID 3041643.

- ↑ Pignata C, Budillon G, Monaco G, Nani E, Cuomo R, Parrilli G, Ciccimarra F (1990). "Jejunal bacterial overgrowth and intestinal permeability in children with immunodeficiency syndromes". Gut. 31 (8): 879–82. PMID 2387510.

- ↑ Abell T, Minocha A (2006). "Gastrointestinal complications of bariatric surgery: diagnosis and therapy". Am J Med Sci. 331 (4): 214–8. PMID 16617237.

- ↑ Laine L, Ahnen D, McClain C, Solcia E, Walsh J (2000). "Review article: potential gastrointestinal effects of long-term acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 14 (6): 651–68. PMID 10848649.

- ↑ Williams C, McColl K (2006). "Review article: proton pump inhibitors and bacterial overgrowth". Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 23 (1): 3–10. PMID 16393275.

- ↑ Craig R, Atkinson A (1988). "D-xylose testing: a review". Gastroenterology. 95 (1): 223–31. PMID 3286361.

- ↑ Corazza G, Menozzi M, Strocchi A, Rasciti L, Vaira D, Lecchini R, Avanzini P, Chezzi C, Gasbarrini G (1990). "The diagnosis of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Reliability of jejunal culture and inadequacy of breath hydrogen testing". Gastroenterology. 98 (2): 302–9. PMID 2295385.

- ↑ Kerlin P, Wong L (1988). "Breath hydrogen testing in bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine". Gastroenterology. 95 (4): 982–8. PMID 3410238.

- ↑ Donald I, Kitchingmam G, Donald F, Kupfer R (1992). "The diagnosis of small bowel bacterial overgrowth in elderly patients". J Am Geriatr Soc. 40 (7): 692–6. PMID 1607585.

- ↑ Toskes P, Giannella R, Jervis H, Rout W, Takeuchi A (1975). "Small intestinal mucosal injury in the experimental blind loop syndrome. Light- and electron-microscopic and histochemical studies". Gastroenterology. 68 (5 Pt 1): 1193–203. PMID 1126607.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Singh VV, Toskes PP (2004). "Small Bowel Bacterial Overgrowth: Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 7 (1): 19–28. PMID 14723835.

- ↑ Attar A, Flourié B, Rambaud J, Franchisseur C, Ruszniewski P, Bouhnik Y (1999). "Antibiotic efficacy in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-related chronic diarrhea: a crossover, randomized trial". Gastroenterology. 117 (4): 794–7. PMID 10500060.