Borrelia burgdorferi

| Borrelia burgdorferi | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||

| Borrelia burgdorferi |

|

Lyme disease Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Borrelia burgdorferi On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Borrelia burgdorferi |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Raviteja Guddeti, M.B.B.S. [2], Ilan Dock, B.S. Template:Seealso Template:Seealso (a newly discovered Borrelia species that has been associated with Lyme disease)

Overview

Borrelia burgdorferi is species of bacteria of the spirochete class of the genus Borrelia. B. burgdorferi is predominant in North America, but also exists in Europe, and is the causative agent of Lyme disease. It is a zoonotic, vector-borne disease transmitted by ticks and is named after the researcher Willy Burgdorfer who first isolated the bacterium in 1982. B. burgdorferi is one of the few pathogenic bacteria that can survive without iron, having replaced all of its iron-sulphur cluster enzymes with enzymes that use manganese, thus avoiding the problem many pathogenic bacteria face in acquiring iron. B. burgdorferi infections have been linked to non-Hodgkin lymphomas.[1]

Organism

- Lyme disease, or Lyme borreliosis, is caused by Gram negative spirochetal bacteria from the genus Borrelia, which has at least 37 known species, 12 of which are Lyme related, and an unknown number of genomic strains. Borrelia species known to cause Lyme disease are collectively known as Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex.

- Borrelia are microaerophillic and slow-growing—the primary reason for the long delays when diagnosing Lyme disease—and have been found to have greater strain diversity than previously estimated.[2] The strains differ in clinical symptoms and/or presentation as well as geographic distribution.[3]

- Except for Borrelia recurrentis (which causes louse-borne relapsing fever and is transmitted by the human body louse), all known species are believed to be transmitted by ticks.[4]

- On February 2016, a second, a new organism, B. mayonii, has been reported for causing Lyme disease (see B. mayonii here).

- Borrelia mayonii causes similar symptoms to Borrelia burgdorferi.

- However, unlike B. burgdorferi, B. mayonii may induce a quick onset of nausea and vomiting.

- The rash associated with this new organism is also different from the conventional, bulls-eye rash. The rash associated with B. mayonii has been reported as a diffuse rash, covering the entire body in "red spots."[5]

Structure and growth

B. burgdorferi is a highly specialized, motile, two-membrane, spiral-shaped spirochete ranging from about 9 to 32 micrometers in length. It is often described as gram-negative and has an outer membrane with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), though it stains only weakly in the Gram stain. B. burgdorferi is a microaerophilic organism, requiring little oxygen to survive. It lives primarily as an extracellular pathogen, although it can also hide intracellularly (see Mechanisms of persistence section).

Like other spirochetes such as T. pallidum (the agent of syphilis), B. burgdorferi has an axial filament composed of flagella which run lengthways between its cell wall and outer membrane. This structure allows the spirochete to move efficiently in corkscrew fashion through viscous media, such as connective tissue. As a result, B. burgdorferi can disseminate throughout the body within days to weeks of infection, penetrating deeply into tissue where the immune system and antibiotics may not be able to eradicate the infection.

B. burgdorferi is very slow growing, with a doubling time of 12-18 hours[6] (in contrast to pathogens such as Streptococcus and Staphylococcus, which have a doubling time of 20-30 minutes). Since most antibiotics kill bacteria only when they are dividing, this longer doubling time necessitates the use of relatively longer treatment courses for Lyme disease. Antibiotics are most effective during the growth phase, which for B. burgdorferi occurs in four-week cycles.

Outer surface proteins

The outer membrane of Borrelia burgdorferi is composed of various unique outer surface proteins (Osp) that have been characterized (OspA through OspF). They are presumed to play a role in virulence.

OspA and OspB are by far the most abundant outer surface proteins.

The OspA and OspB genes encode the major outer membrane proteins of the B. burgdorferi. The two Osp proteins show a high degree of sequence similarity, indicating a recent evolutionary event. Molecular analysis and sequence comparison of OspA and OspB with other proteins has revealed similarity to the signal peptides of prokaryotic lipoproteins.[7]Virtually all spirochetes in the midgut of an unfed nymph tick express OspA.

OspC is an antigen-detection of its presence by the host organism and can stimulate an immune response. While each individual bacterial cell contains just one copy of the gene encoding OspC, populations of B. burgdorferi have shown high levels of variation among individuals in the gene sequence for OspC.[8] OspC is likely to play a role in transmission from vector to host, since it has been observed that the protein is only expressed in the presence of mammalian blood or tissue.[9]

The functions of OspD are unknown.

OspE and OspF are structurally arranged in tandem as one transcriptional unit under the control of a common promoter.[10]

In transmission to the mammalian host, when the nymphal tick begins to feed, and the spirochetes in the midgut begin to multiply rapidly, most spirochetes cease expressing OspA on their surface. Simultaneous with the disappearance of OspA, the spirochete population in the midgut begins to express a OspC. Upregulation of OspC begins during the first day of feeding and peaks 48 hours after attachment.[11]

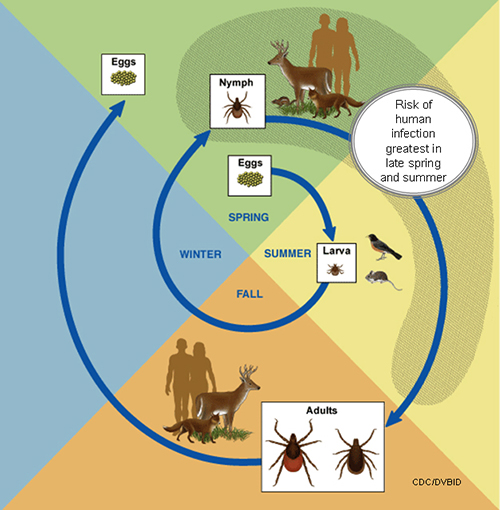

General Tick Life Cycle

A tick's life cycle is composed of four stages: hatching (egg), nymph (six legged), nymph (eight legged), and an adult.

Ticks require blood meal to survive through their life cycle.

Hosts for tick blood meals include mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Ticks will most likely transfer between different hosts during the different stages of their life cycle.

Humans are most often targeted during the nymph and adult stages of the life cycle.

Life cycle is also dependent on seasonal variation.

Ticks will go from eggs to larva during the summer months, infecting bird or rodent host during the larval stage.

Larva will infect the host from the summer until the following spring, at which point they will progress into the nymph stage.

During the nymph stage, a tick will most likely seek a mammal host (including humans).

A nymph will remain with the selected host until the following fall at which point it will progress into an adult.

As an adult, a tick will feed on a mammalian host. However unlike previous stages, ticks will prefer larger mammals over rodents.

The average tick life cycle requires three years for completion.

Different species will undergo certain variations within their individual life cycles. [12]

Borrelia burgdoferi lifecycle

The life-cycle concept encompassing reservoirs and infections in multiple hosts has recently been expanded to encompass forms of the spirochete which differ from the motile corkscrew form, and these include cystic forms spheroplast-like, straighted non-coiled bacillary forms which are immotile due to flagellin mutations and granular forms coccoid in profile. The model of Plasmodium species Malaria with multiple parasitic profiles demonstrable in various host insects and mammals is a hypothesized model for a similarly complex proposed Borrelia spirochete life cycle. [13] [14]

Whereas B. burgdorferi is most associated with deer tick and the white footed mouse,[15] B. afzelii is most frequently detected in rodent-feeding vector ticks, B. garinii and B. valaisiana appear to be associated with birds. Both rodents and birds are competent reservoir hosts for Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. The resistance of a genospecies of Lyme disease spirochetes to the bacteriolytic activities of the alternative immune complement pathway of various host species may determine its reservoir host association.

Ecology

Urbanization and other anthropogenic factors can be implicated in the spread of the Lyme disease into the human population. In many areas, expansion of suburban neighborhoods has led to the gradual deforestation of surrounding wooded areas and increasing "border" contact between humans and tick-dense areas. Human expansion has also resulted in a gradual reduction of the predators that normally hunt deer as well as mice, chipmunks and other small rodents -- the primary reservoirs for Lyme disease. As a consequence of increased human contact with host and vector, the likelihood of transmission of Lyme to residents of endemic area has greatly increased.[16][17] Researchers are also investigating possible links between global warming and the spread of vector-borne diseases including Lyme disease.[18]

The deer tick (Ixodes scapularis, the primary vector in the northeastern U.S.) has a two-year life cycle, first progressing from larva to nymph, and then from nymph to adult. The tick feeds only once at each stage. In the fall, large acorn forests attract deer as well as mice, chipmunks and other small rodents infected with B. burgdorferi. During the following spring, the ticks lay their eggs. The rodent population then "booms." Tick eggs hatch into larvae, which feed on the rodents; thus the larvae acquire infection from the rodents. (Note: At this stage, it is proposed that tick infestation may be controlled using acaricides (miticide).

Adult ticks may also transmit disease to humans. After feeding, female adult ticks lay their eggs on the ground, and the cycle is complete. On the west coast, Lyme disease is spread by the western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus), which has a different life cycle.

The risk of acquiring Lyme disease does not depend on the existence of a local deer population, as is commonly assumed. New research suggests that eliminating deer from smaller areas (less than 2.5 hectares or 6.2 acres) may in fact lead to an increase in tick density and the rise of "tick-borne disease hotspots".[19]

Differentiating B. burgdorferi from B. mayonii

The following table demonstrates key clinical and epidemiological features that distinguish B. burgdorferi from B. mayonii:[20][21]

| General information | B. burgdorferi | B. mayonii

|

|---|---|---|

| Transmission | Tick bite | Tick bite |

| Distribution in the USA | Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Midwest regions | Midwest region |

| Bacteria Concentration in Blood (Spirochetemia) | Lower | Higher |

| Early Symptoms | Fever, headache, rash, neck pain | Fever, headache, rash, neck pain |

| Late Symptoms and Complications | Joint pain and Arthritis | Joint pain and Arthritis |

| Nausea / Vomiting? | No | Yes |

| Rash Characteristics | Bull's-eye target lesion | Diffuse rash |

| Diagnosis | Serology or PCR | Serology or PCR |

| Treatment | Doxycycline | Doxycycline |

Gallery

-

Histopathology showing Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes in Lyme disease. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

White-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus, which is a host of ticks thatare known to carry the bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, responsible for Lyme disease. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

“Corkscrew-shaped” bacteria known as Borrelia burgdorferi, which is the pathogen responsible for causing Lyme disease (400x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Dorsal view of an adult female western blacklegged tick, whichs transmit Borrelia burgdorferi (agent of Lyme disease). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Dorsal view of an adult female western blacklegged tick, whichs transmit Borrelia burgdorferi (agent of Lyme disease). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Dorsal view of engorged female tick, extracted from the skin of a pet cat (26X mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Dorsal view of engorged female tick in the process of obtaining its blood meal (207X magnification). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Scanning electron micrographic (SEM) image depicts dorsal view of engorged female tick (201X magnification). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Photomicrographic montage using the immunofluorescent antibody technique (IFA) used to produce this B. burgdorferi multicolored image. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Lateral view of female deer tick, Ixodes scapularis, with its abdomen engorged with a host blood meal. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Peripheral blood from a newborn child indicates the presence of numerous Borrelia hermsii spirochetes (arrows), consistent with a tickborne relapsing fever (TBRF) infection. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Dorsal view of a soft tick, Ornithodoros hermsi, which is a known vector for the disease tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) (6.5x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Deer tick, Ixodes scapularis. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Dorsal view of engorged female tick in the process of obtaining its blood meal (201x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Dorsal view of engorged female tick, extracted from the skin of a pet cat (26x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Male Dermacentor sp. tick found upon a cat (95x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Dorsal view of male Dermacentor sp. tick found on a cat (3043x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Dorsal view of a female "lone star tick", Amblyomma americanum. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Anterior view of engorged female "lone star tick", Amblyomma americanum. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Ventral view of engorged female "lone star tick" Amblyomma americanum. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

“Corkscrew-shaped” bacteria known as Borrelia burgdorferi, the pathogen responsible for causing Lyme disease (400x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

White-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus, which is a wild rodent reservoir host of ticks, which are known to carry the bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, responsible for Lyme disease. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

This photograph of a whitetail deer, Odocoileus virginianus, was taken during a Lyme disease field investigation in 1993. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

This is a dorsal view of the “soft tick” Carios kelleyi, formerly Ornithodoros kelleyi, or the “Bat Tick”. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

This is a dorsal view of the “soft tick” Carios kelleyi, formerly Ornithodoros kelleyi, or the “Bat Tick”. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

This is a female “Lone star tick”, Amblyomma americanum, and is found in the southeastern and midatlantic United States. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

These "black-legged ticks", Ixodes scapularis, also referred to as I. dammini, are found on a wide rage of hosts including mammals, birds and reptiles. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

Histopathology showing Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes in Lyme disease. Dieterle silver stain. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

-

“Corkscrew-shaped” bacteria known as Borrelia burgdorferi, which is the pathogen responsible for causing Lyme disease (400x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]

References

- ↑ Guidoboni M, Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Doglioni C, Dolcetti R (2006). "Infectious agents in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphomas: pathogenic role and therapeutic perspectives". Clinical lymphoma & myeloma. 6 (4): 289–300. PMID 16507206.

- ↑ Bunikis J, Garpmo U, Tsao J, Berglund J, Fish D, Barbour AG (2004). "Sequence typing reveals extensive strain diversity of the Lyme borreliosis agents Borrelia burgdorferi in North America and Borrelia afzelii in Europe" (PDF). Microbiology. 150 (Pt 6): 1741–55. PMID 15184561.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed. ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Felsenfeld O (1971). Borrelia: Strains, Vectors, Human and Animal Borreliosis. St. Louis: Warren H. Green, Inc.

- ↑ CBS News Lyme Disease. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/lyme-disease-just-got-nastier/ Accessed February 9, 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, R. T. (1984). Genus IV. Borrelia Swellengrebel 1907, 582AL. In Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, vol. 1, pp. 57–62. Edited by N. R. Krieg & J. G. Holt. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Bergstrom S. , Bundoc V.G. , Barbour A.G. Molecular analysis of linear plasmid-encoded major surface proteins, OspA and OspB, of the Lyme disease spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 3 479-486 1989

- ↑ Girschick, J. and Singh, S.E. Molecular survival strategies of the lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Sep, 2004. The Lancet Infectious Diseases: Volume 4, Issue 9, September 2004, Pages 575-583.

- ↑ Fikrig, E. and Pal, U. Adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the vector and vertebrate host. Microbes and Infection Volume 5, Issue 7, June 2003, Pages 659-666. PMID 12787742

- ↑ Lam TT, Nguyen TP, Montgomery RR, Kantor FS, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. Outer surface proteins E and F of Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1994 Jan;62(1):290-8.

- ↑ Schwan TG, Piesman J. Temporal changes in outer surface proteins A and C of the Lyme disease-associated spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, during the chain of infection in ticks and mice. J Clin Microbiol 2000;38:382-8.

- ↑ Life Cycle of Ticks that Bite Humans (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/ticks/life_cycle_and_hosts.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ Macdonald AB. "A life cycle for Borrelia spirochetes?" Med Hypotheses. 2006;67(4):810-8. PMID 16716532

- ↑ Lymeinfo.net - LDAdverseConditions

- ↑ Wallis RC, Brown SE, Kloter KO, Main AJ Jr. Erythema chronicum migrans and lyme arthritis: field study of ticks. Am J Epidemiol. 1978 Oct;108(4):322-7.PMID 727201

- ↑ LoGiudice K, Ostfeld R, Schmidt K, Keesing F (2003). "The ecology of infectious disease: effects of host diversity and community composition on Lyme disease risk". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 100 (2): 567–71. PMID 12525705.

- ↑ Patz J, Daszak P, Tabor G; et al. (2004). "Unhealthy landscapes: Policy recommendations on land use change and infectious disease emergence". Environ Health Perspect. 112 (10): 1092–8. PMID 15238283.

- ↑ Khasnis AA, Nettleman MD (2005). "Global warming and infectious disease". Arch. Med. Res. 36 (6): 689–96. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.03.041. PMID 16216650.

- ↑ Perkins SE, Cattadori IM, Tagliapietra V, Rizzoli AP, Hudson PJ (2006). "Localized deer absence leads to tick amplification". Ecology. 87 (8): 1981–6. PMID 16937637.

- ↑ Pritt, Bobbi S; Mead, Paul S; Johnson, Diep K Hoang; Neitzel, David F; Respicio-Kingry, Laurel B; Davis, Jeffrey P; Schiffman, Elizabeth; Sloan, Lynne M; Schriefer, Martin E; Replogle, Adam J; Paskewitz, Susan M; Ray, Julie A; Bjork, Jenna; Steward, Christopher R; Deedon, Alecia; Lee, Xia; Kingry, Luke C; Miller, Tracy K; Feist, Michelle A; Theel, Elitza S; Patel, Robin; Irish, Cole L; Petersen, Jeannine M (2016). "Identification of a novel pathogenic Borrelia species causing Lyme borreliosis with unusually high spirochaetaemia: a descriptive study". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (5): 556–564. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00464-8. ISSN 1473-3099.

- ↑ "New Lyme-disease-causing bacteria species discovered| CDC Online Newsroom | CDC".

- ↑ 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 22.10 22.11 22.12 22.13 22.14 22.15 22.16 22.17 22.18 22.19 22.20 22.21 22.22 22.23 22.24 22.25 22.26 22.27 22.28 22.29 22.30 22.31 22.32 22.33 22.34 22.35 22.36 22.37 22.38 22.39 22.40 22.41 22.42 "Public Health Image Library (PHIL)".

See Also

- Allen Steere

- Jorge Benach

External Links

- NCBI Borrelia Taxonomy Browser

- Borrelia Microbe Wiki Page

- Borrelia burgdoferi B31 Genome Page==External links==

- Atlas of Borrelia (images of spirochetal, spheroplast and granular forms)

- NCBI Taxonomy Browser - Borrelia

- Borrelia burgdoferi B31 Genome Page

- Borrelia Garinii PBi Genome Page

- Borrelia Afzelli PKo Gemonme Page

- CDC - Vector Interactions and Molecular Adaptations of Lyme Disease and Relapsing Fever Spirochetes Associated with Transmission by Ticks

![Histopathology showing Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes in Lyme disease. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/4/4c/Borrelia44.jpeg)

![White-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus, which is a host of ticks thatare known to carry the bacteria, Borrelia burgdorferi, responsible for Lyme disease. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/3/37/Borrelia38.jpeg)

![“Corkscrew-shaped” bacteria known as Borrelia burgdorferi, which is the pathogen responsible for causing Lyme disease (400x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/e/e4/Borrelia37.jpeg)

![Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/f/f7/Borrelia25.jpeg)

![Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/a/ab/Borrelia26.jpeg)

![Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/a/a0/Borrelia20.jpeg)

![Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/f/fc/Borrelia21.jpeg)

![Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/b/b8/Borrelia22.jpeg)

![Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/7/75/Borrelia23.jpeg)

![Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/1/1d/Borrelia24.jpeg)

![Dorsal view of an adult female western blacklegged tick, whichs transmit Borrelia burgdorferi (agent of Lyme disease). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/e/e2/Anaplasma_phagocytophilum05.jpeg)

![Dorsal view of an adult female western blacklegged tick, whichs transmit Borrelia burgdorferi (agent of Lyme disease). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/0/0f/Anaplasma_phagocytophilum04.jpeg)

![Dorsal view of engorged female tick, extracted from the skin of a pet cat (26X mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/3/3c/Anaplasma_phagocytophilum03.jpeg)

![Dorsal view of engorged female tick in the process of obtaining its blood meal (207X magnification). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/0/09/Anaplasma_phagocytophilum02.jpeg)

![Scanning electron micrographic (SEM) image depicts dorsal view of engorged female tick (201X magnification). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/e/e2/Anaplasma_phagocytophilum01.jpeg)

![Photomicrographic montage using the immunofluorescent antibody technique (IFA) used to produce this B. burgdorferi multicolored image. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/4/43/Borrelia02.jpeg)

![Lateral view of female deer tick, Ixodes scapularis, with its abdomen engorged with a host blood meal. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/e/ed/Borrelia04.jpeg)

![Peripheral blood from a newborn child indicates the presence of numerous Borrelia hermsii spirochetes (arrows), consistent with a tickborne relapsing fever (TBRF) infection. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/9/9b/Borrelia05.jpeg)

![Dorsal view of a soft tick, Ornithodoros hermsi, which is a known vector for the disease tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF) (6.5x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/6/67/Borrelia12.jpeg)

![Deer tick, Ixodes scapularis. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/3/31/Borrelia16.jpeg)

![Dorsal view of engorged female tick in the process of obtaining its blood meal (201x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/5/59/Borrelia27.jpeg)

![Dorsal view of engorged female tick, extracted from the skin of a pet cat (26x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/0/0d/Borrelia28.jpeg)

![Male Dermacentor sp. tick found upon a cat (95x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/3/33/Borrelia29.jpeg)

![Dorsal view of male Dermacentor sp. tick found on a cat (3043x mag). - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/9/96/Borrelia30.jpeg)

![Dorsal view of a female "lone star tick", Amblyomma americanum. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/5/58/Borrelia33.jpeg)

![Anterior view of engorged female "lone star tick", Amblyomma americanum. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/4/41/Borrelia34.jpeg)

![Ventral view of engorged female "lone star tick" Amblyomma americanum. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/a/ab/Borrelia35.jpeg)

![This photograph of a whitetail deer, Odocoileus virginianus, was taken during a Lyme disease field investigation in 1993. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/2/26/Borrelia39.jpeg)

![This is a dorsal view of the “soft tick” Carios kelleyi, formerly Ornithodoros kelleyi, or the “Bat Tick”. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/3/36/Borrelia40.jpeg)

![This is a dorsal view of the “soft tick” Carios kelleyi, formerly Ornithodoros kelleyi, or the “Bat Tick”. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/1/11/Borrelia41.jpeg)

![This is a female “Lone star tick”, Amblyomma americanum, and is found in the southeastern and midatlantic United States. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/5/54/Borrelia42.jpeg)

![These "black-legged ticks", Ixodes scapularis, also referred to as I. dammini, are found on a wide rage of hosts including mammals, birds and reptiles. - Source: Public Health Image Library (PHIL). [22]](/images/0/0e/Borrelia43.jpeg)