Malaria

For patient information click here

|

Malaria Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case studies |

|

Malaria On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Malaria |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

| Malaria | ||

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium falciparum ring-forms and gametocytes in human blood. | ||

| ICD-10 | B50 | |

| ICD-9 | 084 | |

| DiseasesDB | 7728 | |

| MedlinePlus | 000621 | |

| eMedicine | med/1385 emerg/305 ped/1357 | |

| MeSH | C03.752.250.552 | |

Overview

Historical perspective

Epidemiology & Demographics

History & Symptoms

Symptoms of malaria include fever, shivering, arthralgia (joint pain), vomiting, anemia caused by hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, and convulsions. There may be the feeling of tingling in the skin, particularly with malaria caused by P. falciparum. The classical symptom of malaria is cyclical occurrence of sudden coldness followed by rigor and then fever and sweating lasting four to six hours, occurring every two days in P. vivax and P. ovale infections, while every three for P. malariae.[1] P. falciparum can have recurrent fever every 36-48 hours or a less pronounced and almost continuous fever. For reasons that are poorly understood, but which may be related to high intracranial pressure, children with malaria frequently exhibit abnormal posturing, a sign indicating severe brain damage.[2] Malaria has been found to cause cognitive impairments, especially in children. It causes widespread anemia during a period of rapid brain development and also direct brain damage. This neurologic damage results from cerebral malaria to which children are more vulnerable.[3]

Severe malaria is almost exclusively caused by P. falciparum infection and usually arises 6-14 days after infection.[4] Consequences of severe malaria include coma and death if untreated—young children and pregnant women are especially vulnerable. Splenomegaly (enlarged spleen), severe headache, cerebral ischemia, hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), hypoglycemia, and hemoglobinuria with renal failure may occur. Renal failure may cause blackwater fever, where hemoglobin from lysed red blood cells leaks into the urine. Severe malaria can progress extremely rapidly and cause death within hours or days.[4] In the most severe cases of the disease fatality rates can exceed 20%, even with intensive care and treatment.[5] In endemic areas, treatment is often less satisfactory and the overall fatality rate for all cases of malaria can be as high as one in ten.[6] Over the longer term, developmental impairments have been documented in children who have suffered episodes of severe malaria.[7]

Chronic malaria is seen in both P. vivax and P. ovale, but not in P. falciparum. Here, the disease can relapse months or years after exposure, due to the presence of latent parasites in the liver. Describing a case of malaria as cured by observing the disappearance of parasites from the bloodstream can therefore be deceptive. The longest incubation period reported for a P. vivax infection is 30 years.[4] Approximately one in five of P. vivax malaria cases in temperate areas involve overwintering by hypnozoites (i.e., relapses begin the year after the mosquito bite).[8]

Causes of Malaria

Malaria parasites

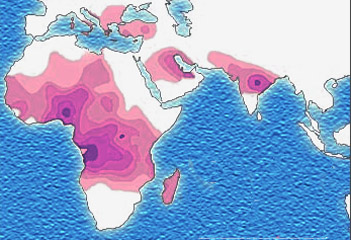

Malaria is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium (phylum Apicomplexa). In humans malaria is caused by P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. vivax. P. vivax is the most common cause of infection, responsible for about 80 % of all malaria cases. However, P. falciparum is the most important cause of disease, and responsible for about 15% of infections and 90% of deaths.[9] Parasitic Plasmodium species also infect birds, reptiles, monkeys, chimpanzees and rodents.[10] There have been documented human infections with several simian species of malaria, namely P. knowlesi, P. inui, P. cynomolgi[11], P. simiovale, P. brazilianum, P. schwetzi and P. simium; however these are mostly of limited public health importance. Although avian malaria can kill chickens and turkeys, this disease does not cause serious economic losses to poultry farmers.[12] However, since being accidentally introduced by humans it has decimated the endemic birds of Hawaii, which evolved in its absence and lack any resistance to it.[13]

Mosquito vectors and the Plasmodium life cycle

The parasite's primary (definitive) hosts and transmission vectors are female mosquitoes of the Anopheles genus. Young mosquitoes first ingest the malaria parasite by feeding on an infected human carrier and the infected Anopheles mosquitoes carry Plasmodium sporozoites in their salivary glands. A mosquito becomes infected when it takes a blood meal from an infected human. Once ingested, the parasite gametocytes taken up in the blood will further differentiate into male or female gametes and then fuse in the mosquito gut. This produces an ookinete that penetrates the gut lining and produces an oocyst in the gut wall. When the oocyst ruptures, it releases sporozoites that migrate through the mosquito's body to the salivary glands, where they are then ready to infect a new human host. This type of transmission is occasionally referred to as anterior station transfer.[14] The sporozoites are injected into the skin, alongside saliva, when the mosquito takes a subsequent blood meal.

Only female mosquitoes feed on blood, thus males do not transmit the disease. The females of the Anopheles genus of mosquito prefer to feed at night. They usually start searching for a meal at dusk, and will continue throughout the night until taking a meal. Malaria parasites can also be transmitted by blood transfusions, although this is rare.[15]

Pathophysiology

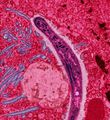

Malaria in humans develops via two phases: an exoerythrocytic (hepatic) and an erythrocytic phase. When an infected mosquito pierces a person's skin to take a blood meal, sporozoites in the mosquito's saliva enter the bloodstream and migrate to the liver. Within 30 minutes of being introduced into the human host, they infect hepatocytes, multiplying asexually and asymptomatically for a period of 6–15 days. Once in the liver these organisms differentiate to yield thousands of merozoites which, following rupture of their host cells, escape into the blood and infect red blood cells, thus beginning the erythrocytic stage of the life cycle.[16] The parasite escapes from the liver undetected by wrapping itself in the cell membrane of the infected host liver cell.[17]

Within the red blood cells the parasites multiply further, again asexually, periodically breaking out of their hosts to invade fresh red blood cells. Several such amplification cycles occur. Thus, classical descriptions of waves of fever arise from simultaneous waves of merozoites escaping and infecting red blood cells.

Some P. vivax and P. ovale sporozoites do not immediately develop into exoerythrocytic-phase merozoites, but instead produce hypnozoites that remain dormant for periods ranging from several months (6–12 months is typical) to as long as three years. After a period of dormancy, they reactivate and produce merozoites. Hypnozoites are responsible for long incubation and late relapses in these two species of malaria.[18]

The parasite is relatively protected from attack by the body's immune system because for most of its human life cycle it resides within the liver and blood cells and is relatively invisible to immune surveillance. However, circulating infected blood cells are destroyed in the spleen. To avoid this fate, the P. falciparum parasite displays adhesive proteins on the surface of the infected blood cells, causing the blood cells to stick to the walls of small blood vessels, thereby sequestering the parasite from passage through the general circulation and the spleen.[19] This "stickiness" is the main factor giving rise to hemorrhagic complications of malaria. High endothelial venules (the smallest branches of the circulatory system) can be blocked by the attachment of masses of these infected red blood cells. The blockage of these vessels causes symptoms such as in placental and cerebral malaria. In cerebral malaria the sequestrated red blood cells can breach the blood brain barrier possibly leading to coma.[20]

Although the red blood cell surface adhesive proteins (called PfEMP1, for Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1) are exposed to the immune system they do not serve as good immune targets because of their extreme diversity; there are at least 60 variations of the protein within a single parasite and perhaps limitless versions within parasite populations.[19] Like a thief changing disguises or a spy with multiple passports, the parasite switches between a broad repertoire of PfEMP1 surface proteins, thus staying one step ahead of the pursuing immune system.

Some merozoites turn into male and female gametocytes. If a mosquito pierces the skin of an infected person, it potentially picks up gametocytes within the blood. Fertilization and sexual recombination of the parasite occurs in the mosquito's gut, thereby defining the mosquito as the definitive host of the disease. New sporozoites develop and travel to the mosquito's salivary gland, completing the cycle. Pregnant women are especially attractive to the mosquitoes,[21] and malaria in pregnant women is an important cause of stillbirths, infant mortality and low birth weight.[22]

Evolutionary pressure of malaria on human genes

Malaria is thought to have been the greatest selective pressure on the human genome in recent history.[23] This is due to the high levels of mortality and morbidity caused by malaria, especially the P. falciparum species.

Sickle-cell disease

The best-studied influence of the malaria parasite upon the human genome is the blood disease, sickle-cell disease. In sickle-cell disease, there is a mutation in the HBB gene, which encodes the beta globin subunit of haemoglobin. The normal allele encodes a glutamate at position six of the beta globin protein, while the sickle-cell allele encodes a valine. This change from a hydrophilic to a hydrophobic amino acid encourages binding between haemoglobin molecules, with polymerization of haemoglobin deforming red blood cells into a "sickle" shape. Such deformed cells are cleared rapidly from the blood, mainly in the spleen, for destruction and recycling.

In the merozoite stage of its life cycle the malaria parasite lives inside red blood cells, and its metabolism changes the internal chemistry of the red blood cell. Infected cells normally survive until the parasite reproduces, but if the red cell contains a mixture of sickle and normal haemoglobin, it is likely to become deformed and be destroyed before the daughter parasites emerge. Thus, individuals heterozygous for the mutated allele, known as sickle-cell trait, may have a low and usually unimportant level of anaemia, but also have a greatly reduced chance of serious malaria infection. This is a classic example of heterozygote advantage.

Individuals homozygous for the mutation have full sickle-cell disease and in traditional societies rarely live beyond adolescence. However, in populations where malaria is endemic, the frequency of sickle-cell genes is around 10%. The existence of four haplotypes of sickle-type hemoglobin suggests that this mutation has emerged independently at least four times in malaria-endemic areas, further demonstrating its evolutionary advantage in such affected regions. There are also other mutations of the HBB gene that produce haemoglobin molecules capable of conferring similar resistance to malaria infection. These mutations produce haemoglobin types HbE and HbC which are common in Southeast Asia and Western Africa, respectively.

Thalassaemias

Another well documented set of mutations found in the human genome associated with malaria are those involved in causing blood disorders known as thalassaemias. Studies in Sardinia and Papua New Guinea have found that the gene frequency of β-thalassaemias is related to the level of malarial endemicity in a given population. A study on more than 500 children in Liberia found that those with β-thalassaemia had a 50% decreased chance of getting clinical malaria. Similar studies have found links between gene frequency and malaria endemicity in the α+ form of α-thalassaemia. Presumably these genes have also been selected in the course of human evolution.

Duffy antigens

The Duffy antigens are antigens expressed on red blood cells and other cells in the body acting as a chemokine receptor. The expression of Duffy antigens on blood cells is encoded by Fy genes (Fya, Fyb, Fyc etc.). Plasmodium vivax malaria uses the Duffy antigen to enter blood cells. However, it is possible to express no Duffy antigen on red blood cells (Fy-/Fy-). This genotype confers complete resistance to P. vivax infection. The genotype is very rare in European, Asian and American populations, but is found in almost all of the indigenous population of West and Central Africa.[24] This is thought to be due to very high exposure to P. vivax in Africa in the last few thousand years.

G6PD

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) is an enzyme which normally protects from the effects of oxidative stress in red blood cells. However, a genetic deficiency in this enzyme results in increased protection against severe malaria.

HLA and interleukin-4

HLA-B53 is associated with low risk of severe malaria. This MHC class I molecule presents liver stage and sporozoite antigens to T-Cells. Interleukin-4, encoded by IL4, is produced by activated T cells and promotes proliferation and differentiation of antibody-producing B cells. A study of the Fulani of Burkina Faso, who have both fewer malaria attacks and higher levels of antimalarial antibodies than do neighboring ethnic groups, found that the IL4-524 T allele was associated with elevated antibody levels against malaria antigens, which raises the possibility that this might be a factor in increased resistance to malaria.[25]

Diagnosis

Lab Tests

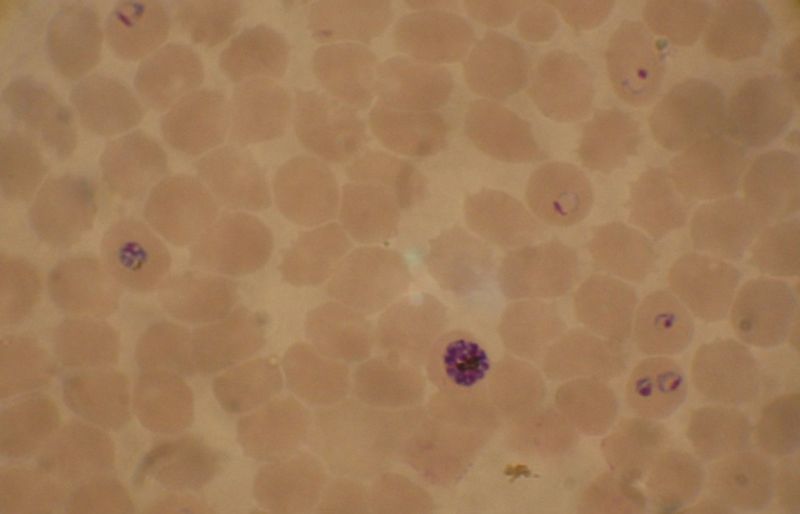

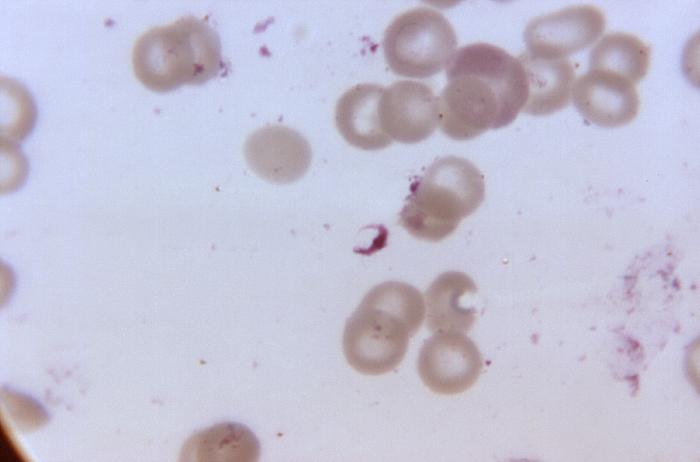

The most economic, preferred, and reliable diagnosis of malaria is microscopic examination of blood films because each of the four major parasite species has distinguishing characteristics. Two sorts of blood film are traditionally used. Thin films are similar to usual blood films and allow species identification because the parasite's appearance is best preserved in this preparation. Thick films allow the microscopist to screen a larger volume of blood and are about eleven times more sensitive than the thin film, so picking up low levels of infection is easier on the thick film, but the appearance of the parasite is much more distorted and therefore distinguishing between the different species can be much more difficult. With the pros and cons of both thick and thin smears taken into consideration, it is imperative to utilize both smears while attempting to make a definitive diagnosis.[26]

From the thick film, an experienced microscopist can detect parasite levels (or parasitemia) down to as low as 0.0000001% of red blood cells. Microscopic diagnosis can be difficult because the early trophozoites ("ring form") of all four species look identical and it is never possible to diagnose species on the basis of a single ring form; species identification is always based on several trophozoites. Please refer to the articles on each parasite for their microscopic appearances: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae.

In areas where microscopy is not available, or where laboratory staff are not experienced at malaria diagnosis, there are antigen detection tests that require only a drop of blood.[27] OptiMAL-IT® will reliably detect falciparum down to 0.01% parasitemia and non-falciparum down to 0.1%. Paracheck-Pf® will detect parasitemias down to 0.002% but will not distinguish between falciparum and non-falciparum malaria. Parasite nucleic acids are detected using polymerase chain reaction. This technique is more accurate than microscopy. However, it is expensive, and requires a specialized laboratory. Moreover, levels of parasitemia are not necessarily correlative with the progression of disease, particularly when the parasite is able to adhere to blood vessel walls. Therefore more sensitive, low-tech diagnosis tools need to be developed in order to detect low levels of parasitaemia in the field. Areas that cannot afford even simple laboratory diagnostic tests often use only a history of subjective fever as the indication to treat for malaria. Using Giemsa-stained blood smears from children in Malawi, one study showed that unnecessary treatment for malaria was significantly decreased when clinical predictors (rectal temperature, nailbed pallor, and splenomegaly) were used as treatment indications, rather than the current national policy of using only a history of subjective fevers (sensitivity increased from 21% to 41%). [28]

Molecular methods are available in some clinical laboratories and rapid real-time assays (for example, QT-NASBA based on the polymerase chain reaction)[29] are being developed with the hope of being able to deploy them in endemic areas.

Severe malaria is commonly misdiagnosed in Africa, leading to a failure to treat other life-threatening illnesses. In malaria-endemic areas, parasitemia does not ensure a diagnosis of severe malaria because parasitemia can be incidental to other concurrent disease. Recent investigations suggest that malarial retinopathy is better (collective sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 90%) than any other clinical or laboratory feature in distinguishing malarial from non-malarial coma.[30]

-

Blood smear from a P. falciparum culture (K1 strain). Several red blood cells have ring stages inside them. Close to the center there is a schizont and on the left a trophozoite.

-

Malaria (organisms in cells)

Treatment

Active malaria infection with P. falciparum is a medical emergency requiring hospitalization. Infection with P. vivax, P. ovale or P. malariae can often be treated on an outpatient basis. Treatment of malaria involves supportive measures as well as specific antimalarial drugs. When properly treated, someone with malaria can expect a complete cure.[31]

Medical Therapy

Antimalarial drugs

There are several families of drugs used to treat malaria. Chloroquine is very cheap and, until recently, was very effective, which made it the antimalarial drug of choice for many years in most parts of the world. However, resistance of Plasmodium falciparum to chloroquine has spread recently from Asia to Africa, making the drug ineffective against the most dangerous Plasmodium strain in many affected regions of the world. In those areas where chloroquine is still effective it remains the first choice. Unfortunately, chloroquine-resistance is associated with reduced sensitivity to other drugs such as quinine and amodiaquine.[32]

There are several other substances which are used for treatment and, partially, for prevention (prophylaxis). Many drugs may be used for both purposes; larger doses are used to treat cases of malaria. Their deployment depends mainly on the frequency of resistant parasites in the area where the drug is used. One drug currently being investigated for possible use as an anti-malarial, especially for treatment of drug-resistant strains, is the beta blocker propranolol. Propranolol has been shown to block both Plasmodium's ability to enter red blood cell and establish an infection, as well as parasite replication. A December 2006 study by Northwestern University researchers suggested that propranolol may reduce the dosages required for existing drugs to be effective against P. falciparum by 5- to 10-fold, suggesting a role in combination therapies.[33]

Currently available anti-malarial drugs include:[34]

- Artemether-lumefantrine (Therapy only, commercial names Coartem® and Riamet®)

- Artesunate-amodiaquine (Therapy only)

- Artesunate-mefloquine (Therapy only)

- Artesunate-Sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (Therapy only)

- Atovaquone-proguanil, trade name Malarone (Therapy and prophylaxis)

- Quinine (Therapy only)

- Chloroquine (Therapy and prophylaxis; usefulness now reduced due to resistance)

- Cotrifazid (Therapy and prophylaxis)

- Doxycycline (Therapy and prophylaxis)

- Mefloquine, trade name Lariam (Therapy and prophylaxis)

- Primaquine (Therapy in P. vivax and P. ovale only; not for prophylaxis)

- Proguanil (Prophylaxis only)

- Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (Therapy; prophylaxis for semi-immune pregnant women in endemic countries as "Intermittent Preventive Treatment" - IPT)

- Hydroxychloroquine, trade name Plaquenil (Therapy and prophylaxis)

The development of drugs was facilitated when Plasmodium falciparum was successfully cultured.[35] This allowed in vitro testing of new drug candidates.

Extracts of the plant Artemisia annua, containing the compound artemisinin or semi-synthetic derivatives (a substance unrelated to quinine), offer over 90% efficacy rates, but their supply is not meeting demand.[36] One study in Rwanda showed that children with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria demonstrated fewer clinical and parasitological failures on post-treatment day 28 when amodiaquine was combined with artesunate, rather than administered alone (OR = 0.34). However, increased resistance to amodiaquine during this study period was also noted. [37] Since 2001 the World Health Organization has recommended using artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) as first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria in areas experiencing resistance to older medications. The most recent WHO treatment guidelines for malaria recommend four different ACTs. While numerous countries, including most African nations, have adopted the change in their official malaria treatment policies, cost remains a major barrier to ACT implementation. Because ACTs cost up to twenty times as much as older medications, they remain unaffordable in many malaria-endemic countries. The molecular target of artemisinin is controversial, although recent studies suggest that SERCA, a calcium pump in the endoplasmic reticulum may be associated with artemisinin resistance.[38] Malaria parasites can develop resistance to artemisinin and resistance can be produced by mutation of SERCA.[39] However, other studies suggest the mitochondrion is the major target for artemisinin and its analogs.[40]

In February 2002, the journal Science and other press outlets[41] announced progress on a new treatment for infected individuals. A team of French and South African researchers had identified a new drug they were calling "G25".[42] It cured malaria in test primates by blocking the ability of the parasite to copy itself within the red blood cells of its victims. In 2005 the same team of researchers published their research on achieving an oral form, which they refer to as "TE3" or "te3".[43] As of early 2006, there is no information in the mainstream press as to when this family of drugs will become commercially available.

In 1996, Professor Geoff McFadden stumbled upon the work of British biologist Ian Wilson, who had discovered that the plasmodia responsible for causing malaria retained parts of chloroplasts[44], an organelle usually found in plants, complete with their own functioning genomes. This led Professor McFadden to the realisation that any number of herbicides may in fact be successful in the fight against malaria, and so he set about trialing large numbers of them, and enjoyed a 75% success rate.

These "apicoplasts" are thought to have originated through the endosymbiosis of algae[45] and play a crucial role in fatty acid bio-synthesis in plasmodia[46]. To date, 466 proteins have been found to be produced by apicoplasts[47] and these are now being looked at as possible targets for novel anti-malarial drugs.

Although effective anti-malarial drugs are on the market, the disease remains a threat to people living in endemic areas who have no proper and prompt access to effective drugs. Access to pharmacies and health facilities, as well as drug costs, are major obstacles. Médecins Sans Frontières estimates that the cost of treating a malaria-infected person in an endemic country was between US$0.25 and $2.40 per dose in 2002.[48]

Counterfeit drugs

Sophisticated counterfeits have been found in Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia[49] and China,[50] and are an important cause of avoidable death in these countries.[51] There is no reliable way for doctors or lay people to detect counterfeit drugs without help from a laboratory. Companies are attempting to combat the persistence of counterfeit drugs by using new technology to provide security from source to distribution.

Primary Prevention

References

- ↑ Malaria life cycle & pathogenesis. Malaria in Armenia. Accessed October 31, 2006.

- ↑ Idro, R. "Decorticate, decerebrate and opisthotonic posturing and seizures in Kenyan children with cerebral malaria". Malaria Journal. 4 (57). PMID 16336645. Retrieved 2007-01-21. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Boivin, M.J., "Effects of early cerebral malaria on cognitive ability in Senegalese children," Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 23, no. 5 (October 2002): 353–64. Holding, P.A. and Snow, R.W., "Impact of Plasmodium falciparum malaria on performance and learning: review of the evidence," American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 64, suppl. nos. 1–2 (January–February 2001): 68–75.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Trampuz A, Jereb M, Muzlovic I, Prabhu R (2003). "Clinical review: Severe malaria". Crit Care. 7 (4): 315–23. PMID 12930555.

- ↑ Kain K, Harrington M, Tennyson S, Keystone J (1998). "Imported malaria: prospective analysis of problems in diagnosis and management". Clin Infect Dis. 27 (1): 142–9. PMID 9675468.

- ↑ Mockenhaupt F, Ehrhardt S, Burkhardt J, Bosomtwe S, Laryea S, Anemana S, Otchwemah R, Cramer J, Dietz E, Gellert S, Bienzle U (2004). "Manifestation and outcome of severe malaria in children in northern Ghana". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 71 (2): 167–72. PMID 15306705.

- ↑ Carter JA, Ross AJ, Neville BG, Obiero E, Katana K, Mung'ala-Odera V, Lees JA, Newton CR (2005). "Developmental impairments following severe falciparum malaria in children". Trop Med Int Health. 10: 3–10. PMID 15655008.

- ↑ Adak T, Sharma V, Orlov V (1998). "Studies on the Plasmodium vivax relapse pattern in Delhi, India". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 59 (1): 175–9. PMID 9684649.

- ↑ Mendis K, Sina B, Marchesini P, Carter R (2001). "The neglected burden of Plasmodium vivax malaria" (PDF). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 64 (1-2 Suppl): 97–106. PMID 11425182.

- ↑ Escalante A, Ayala F (1994). "Phylogeny of the malarial genus Plasmodium, derived from rRNA gene sequences". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 91 (24): 11373–7. PMID 7972067.

- ↑ Garnham, PCC (1966). Malaria parasites and other haemosporidia. Blackwell Scientific Publications. Unknown parameter

|Location=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ↑ Investing in Animal Health Research to Alleviate Poverty. International Livestock Research Institute. Permin A. and Madsen M. (2001) Appendix 2: review on disease occurrence and impact (smallholder poultry). Accessed 29 Oct 2006

- ↑ Atkinson CT, Woods KL, Dusek RJ, Sileo LS, Iko WM (1995). "Wildlife disease and conservation in Hawaii: pathogenicity of avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum) in experimentally infected iiwi (Vestiaria coccinea)". Parasitology. 111 Suppl: S59–69. PMID 8632925.

- ↑ Talman A, Domarle O, McKenzie F, Ariey F, Robert V. "Gametocytogenesis: the puberty of Plasmodium falciparum". Malar J. 3: 24. PMID 15253774.

- ↑ Marcucci C, Madjdpour C, Spahn D. "Allogeneic blood transfusions: benefit, risks and clinical indications in countries with a low or high human development index". Br Med Bull. 70: 15–28. PMID 15339855.

- ↑ Bledsoe, G. H. (December 2005) "Malaria primer for clinicians in the United States" Southern Medical Journal 98(12): pp. 1197-204, (PMID: 16440920);

- ↑ Sturm A,

Amino R, van de Sand C, Regen T, Retzlaff S, Rennenberg A, Krueger A, Pollok JM, Menard R, Heussler VT (2006). "Manipulation of host hepatocytes by the malaria parasite for delivery into liver sinusoids". Science. 313: 1287–1490. PMID 16888102. line feed character in

|author=at position 10 (help) - ↑ Cogswell F (1992). "The hypnozoite and relapse in primate malaria". Clin Microbiol Rev. 5 (1): 26–35. PMID 1735093.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Chen Q, Schlichtherle M, Wahlgren M (2000). "Molecular aspects of severe malaria". Clin Microbiol Rev. 13 (3): 439–50. PMID 10885986.

- ↑ Adams S, Brown H, Turner G (2002). "Breaking down the blood-brain barrier: signaling a path to cerebral malaria?". Trends Parasitol. 18 (8): 360–6. PMID 12377286.

- ↑ Lindsay S, Ansell J, Selman C, Cox V, Hamilton K, Walraven G (2000). "Effect of pregnancy on exposure to malaria mosquitoes". Lancet. 355 (9219): 1972. PMID 10859048.

- ↑ van Geertruyden J, Thomas F, Erhart A, D'Alessandro U (2004). "The contribution of malaria in pregnancy to perinatal mortality". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 71 (2 Suppl): 35–40. PMID 15331817.

- ↑ Kwiatkowski, DP (2005). "How Malaria Has Affected the Human Genome and What Human Genetics Can Teach Us about Malaria". Am J Hum Genet. 77: 171–92. PMID 16001361.

- ↑ Carter R, Mendis KN (2002). "Evolutionary and historical aspects of the burden of malaria". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15 (4): 564–94. PMID 12364370.

- ↑ Verra F, Luoni G, Calissano C, Troye-Blomberg M, Perlmann P, Perlmann H, Arcà B, Sirima B, Konaté A, Coluzzi M, Kwiatkowski D, Modiano D (2004). "IL4-589C/T polymorphism and IgE levels in severe malaria". Acta Trop. 90 (2): 205–9. PMID 15177147.

- ↑ Warhurst DC, Williams JE (1996). "Laboratory diagnosis of malaria". J Clin Pathol. 49: 533–38. PMID 8813948.

- ↑ Pattanasin S, Proux S, Chompasuk D, Luwiradaj K, Jacquier P, Looareesuwan S, Nosten F (2003). "Evaluation of a new Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase assay (OptiMAL-IT®) for the detection of malaria". Transact Royal Soc Trop Med. 97: 672–4. PMID 16117960.

- ↑ Redd S, Kazembe P, Luby S, Nwanyanwu O, Hightower A, Ziba C, Wirima J, Chitsulo L, Franco C, Olivar M (1996). "Clinical algorithm for treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children". Lancet. 347 (8996): 223–7. PMID 8551881..

- ↑ Mens PF, Schoone GJ, Kager PA, Schallig HDFH. (2006). "Detection and identification of human Plasmodium species with real-time quantitative nucleic acid sequence-based amplification". Malaria Journal. 5 (80). doi:10.1186/1475-2875-5-80.

- ↑ Beare NA et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006 Nov;75(5):790-797.

- ↑ If I get malaria, will I have it for the rest of my life? CDC publication, Accessed 14 Nov 2006

- ↑ Tinto H, Rwagacondo C, Karema C; et al. "In-vitro susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to monodesethylamodiaquine, dihydroartemsinin and quinine in an area of high chloroquine resistance in Rwanda". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 100 (6): 509&ndash, 14. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.09.018.

- ↑ Murphy S, Harrison T, Hamm H, Lomasney J, Mohandas N, Haldar K (2006). "Erythrocyte G protein as a novel target for malarial chemotherapy". PLoS Med. 3 (12): e528. PMID 17194200. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Prescription drugs for malaria Retrieved February 27, 2007.

- ↑ Trager W, Jensen JB. (1976). "Human malaria parasites in continuous culture". Science. 193(4254): 673&ndash, 5. PMID 781840.

- ↑ Senior K (2005). "Shortfall in front-line antimalarial drug likely in 2005". Lancet Infect Dis. 5 (2): 75. PMID 15702504.

- ↑ Rwagacondo C, Karema C, Mugisha V, Erhart A, Dujardin J, Van Overmeir C, Ringwald P, D'Alessandro U (2004). "Is amodiaquine failing in Rwanda? Efficacy of amodiaquine alone and combined with artesunate in children with uncomplicated malaria". Trop Med Int Health. 9 (10): 1091–8. PMID 15482401..

- ↑ Eckstein-Ludwig U, Webb R, Van Goethem I, East J, Lee A, Kimura M, O'Neill P, Bray P, Ward S, Krishna S (2003). "Artemisinins target the SERCA of Plasmodium falciparum". Nature. 424 (6951): 957–61. PMID 12931192.

- ↑ Uhlemann A, Cameron A, Eckstein-Ludwig U, Fischbarg J, Iserovich P, Zuniga F, East M, Lee A, Brady L, Haynes R, Krishna S (2005). "A single amino acid residue may determine the sensitivity of SER`CAs to artemisinins". Nat Struct Mol Biol. 12 (7): 628–9. PMID 15937493.

- ↑ Li W, Mo W, Shen D, Sun L, Wang J, Lu S, Gitschier J, Zhou B (2005). "Yeast model uncovers dual roles of mitochondria in action of artemisinin". PLoS Genet. 1 (3): e36. PMID 16170412.

- ↑ Malaria drug offers new hope. BBC News 2002-02-15.

- ↑ One step closer to conquering malaria

- ↑ Salom-Roig, X. et al. (2005) Dual molecules as new antimalarials. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening 8:49-62.

- ↑ "Herbicides as a treatment for malaria". Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ↑ Khöler, Sabine (1997). "A Plastid of Probable Green Algal Origin in Apicomplexan Parasites". Science. 275 (5305): 1485–1489. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Gardner, Malcom (1998). "Chromosome 2 Sequence of the Human Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum". Science. 282 (5391): 1126–1132. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Foth, Bernado (2003). "Dissecting Apicoplast Targeting in the Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum". Science. 299 (5607): 705–708. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Medecins Sans Frontieres, "What is the Cost and Who Will Pay?"

- ↑ Lon CT, Tsuyuoka R, Phanouvong S; et al. (2006). "Counterfeit and substandard antimalarial drugs in Cambodia". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 100 (11): 1019&ndash, 24. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.01.003.

- ↑ U. S. Pharmacopeia (2004). "Fake antimalarials found in Yunan province, China" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- ↑ Newton PN, Green MD, Fernández FM, Day NPJ, White NJ. (2006). "Counterfeit anti-infective drugs". Lancet Infect Dis. 6 (9): 602&ndash, 13. PMID 16931411.

External links

- National Geographic July 2007 Issue on Malaria

- WHO site on malaria

- Template:McGrawHillAnimation

- Johns Hopkins Malariology Open Courseware

- www.malariacontrol.net distributed computing project for the fight against malaria

- United States Centers for Disease Control - Malaria information pages

- Doctors Without Borders/Medecins Sans Frontieres - Malaria information pages

- HRC/Eldis Health Resource Guide - Malaria research and resources on health in developing countries

- Medline Plus - Malaria

- Interview with Dr Andrew Speilman, Harvard malaria specialist

- Malaria Consortium website

- GlobalHealthFacts.org Malaria Cases and Deaths by Country

- Survey article: History of malaria around the North Sea

- DriveAgainstMalaria.org, "World's longest journey to fight the biggest killer of children"

- Malaria on JHSPH OpenCourseWare

- Malaria Foundation International

- Malaria Atlas Project

- UNITAID, International Facility for the Purchase of Drugs (Wikipedia Article)

- BBC - Hopes of Malaria Vaccine by 2010 15 October 2004

- BBC - Science shows how malaria hides 8 April 2005

- History of discoveries in malaria

- Malaria. The UNICEF-UNDP-World Bank-WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases

- Malaria Vaccine Initiative

- Story of the discovery of the vector of the malarial parasite

- Wellcome Trust against Malaria

- "Vaccines for Development" - Blog on vaccine research and production for developing countries

- Medicines for Malaria Venture

- Malaria and Mosquitos - questions and answers

- Hisnets - Fighting Malaria: One Net At A Time

- Call for Increased Production of Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets as Part of the U.N. Millenium Campaign

- Providing everyone with a LLIN in Sahn Malen, a small village in Sierra Leone

- Burden of Malaria, BBC pictures relating to malaria in northern Uganda

- Malaria: Cooperation among Parasite, Vector, and Host (Animation)

Template:Link FA Template:Protozoal diseases

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA af:Malaria ar:ملاريا zh-min-nan:Ma-lá-lí-á bs:Malarija bg:Малария ca:Malària cs:Malárie da:Malaria de:Malaria el:Ελονοσία eo:Malario eu:Malaria gl:Malaria ko:말라리아 hi:शीतज्वर hr:Malarija id:Malaria ia:Malaria it:Malaria he:מלריה ka:მალარია hu:Malária mt:Malarja ms:Malaria nl:Malaria no:Malaria om:Malaria ps:ملاريا qu:Chukchu simple:Malaria sk:Malária sl:Malarija sr:Маларија sh:Malarija su:Malaria fi:Malaria sv:Malaria ta:மலேரியா te:మలేరియా th:มาลาเรีย uk:Малярія

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 errors: invisible characters

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- Apicomplexa

- Insect-borne diseases

- Malaria

- Emergency medicine

- Parasitic diseases

- Tropical disease

- Deaths from malaria

- Infectious disease

- Mature chapter

- Overview complete