Insulin

|

WikiDoc Resources for Insulin |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Insulin |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Insulin at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Insulin at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Insulin

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Insulin Risk calculators and risk factors for Insulin

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Insulin |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Phone:617-632-7753

Insulin is an animal hormone whose presence informs the body's cells that the animal is well fed, causing liver and muscle cells to take in glucose and store it in the form of glycogen, and causing fat cells to take in blood lipids and turn them into triglycerides. In addition it has several other anabolic effects throughout the body.

Insulin is used medically to treat some forms of diabetes mellitus. Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus depend on external insulin (most commonly injected subcutaneously) for their survival because of the absence of the hormone. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus have insulin resistance, relatively low insulin production, or both; some type 2 diabetics eventually require insulin when other medications become insufficient in controlling blood glucose levels.

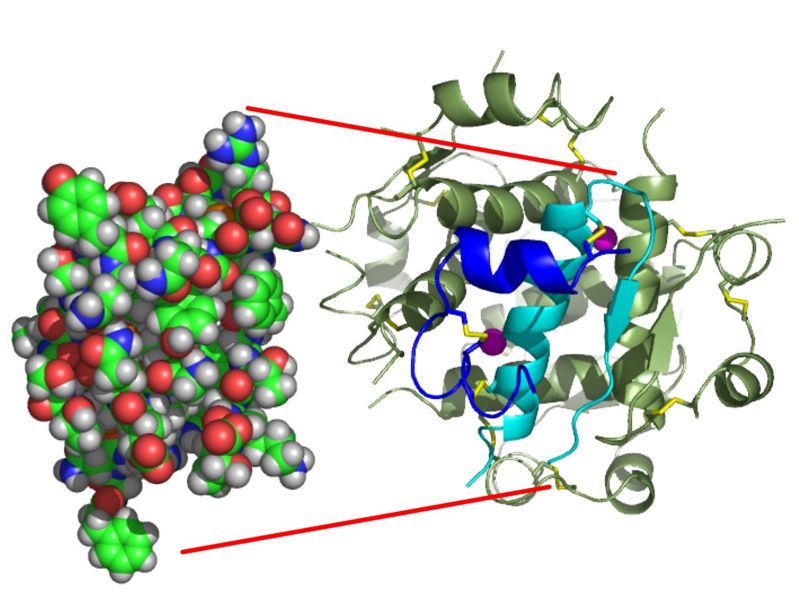

Insulin is a peptide hormone composed of 51 amino acid residues and has a molecular weight of 5808 Da. It is produced in the Islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. The name comes from the Latin insula for "island".

Insulin's genetic structure varies marginally between species of animal. Insulin from animal sources differs somewhat in regulatory function strength (i.e., in carbohydrate metabolism) in humans because of those variations. Porcine (pig) insulin is especially close to the human version.

Discovery and characterization

In 1869 Paul Langerhans, a medical student in Berlin, was studying the structure of the pancreas (the jelly-like gland behind the stomach) under a microscope when he identified some previously un-noticed tissue clumps scattered throughout the bulk of the pancreas. The function of the "little heaps of cells," later known as the Islets of Langerhans, was unknown, but Edouard Laguesse later suggested that they might produce secretions that play a regulatory role in digestion. Paul Langerhans' son, Archibald, also helped to understand this regulatory role.

In 1889, the Polish-German physician Oscar Minkowski in collaboration with Joseph von Mering removed the pancreas from a healthy dog to test its assumed role in digestion. Several days after the dog's pancreas was removed, Minkowski's animal keeper noticed a swarm of flies feeding on the dog's urine. On testing the urine they found that there was sugar in the dog's urine, establishing for the first time a relationship between the pancreas and diabetes. In 1901, another major step was taken by Eugene Opie, when he clearly established the link between the Islets of Langerhans and diabetes: Diabetes mellitus … is caused by destruction of the islets of Langerhans and occurs only when these bodies are in part or wholly destroyed. Before his work, the link between the pancreas and diabetes was clear, but not the specific role of the islets.

Over the next two decades, several attempts were made to isolate whatever it was the islets produced as a potential treatment. In 1906 George Ludwig Zuelzer was partially successful treating dogs with pancreatic extract but was unable to continue his work. Between 1911 and 1912, E.L. Scott at the University of Chicago used aqueous pancreatic extracts and noted a slight diminution of glycosuria but was unable to convince his director of his work's value; it was shut down. Israel Kleiner demonstrated similar effects at Rockefeller University in 1919, but his work was interrupted by World War I and he did not return to it. Nicolae Paulescu, a professor of physiology at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Bucharest, published similar work in 1921 that had been carried out in France. Use of his techniques was patented in Romania, though no clinical use resulted.[1]

In October 1920, Frederick Banting was reading one of Minkowski's papers and concluded that it is the very digestive secretions that Minkowski had originally studied that were breaking down the islet secretion(s), thereby making it impossible to extract successfully. He jotted a note to himself Ligate pancreatic ducts of the dog. Keep dogs alive till acini degenerate leaving islets. Try to isolate internal secretion of these and relieve glycosurea.

The idea was that the pancreas's internal secretion, which supposedly regulates sugar in the bloodstream, might hold the key to the treatment of diabetes.

He travelled to Toronto to meet with J.J.R. Macleod, who was not entirely impressed with his idea – so many before him had tried and failed. Nevertheless, he supplied Banting with a lab at the University, an assistant (medical student Charles Best), and 10 dogs, then left on vacation during the summer of 1921. Their method was tying a ligature (string) around the pancreatic duct, and, when examined several weeks later, the pancreatic digestive cells had died and been absorbed by the immune system, leaving thousands of islets. They then isolated an extract from these islets, producing what they called isletin (what we now know as insulin), and tested this extract on the dogs. Banting and Best were then able to keep a pancreatectomized dog alive all summer because the extract lowered the level of sugar in the blood.

Macleod saw the value of the research on his return but demanded a re-run to prove the method actually worked. Several weeks later it was clear the second run was also a success, and he helped publish their results privately in Toronto that November. However, they needed six weeks to extract the isletin, which forced considerable delays. Banting suggested that they try to use fetal calf pancreas, which had not yet developed digestive glands; he was relieved to find that this method worked well. With the supply problem solved, the next major effort was to purify the extract. In December 1921, Macleod invited the biochemist James Collip to help with this task, and, within a month, the team felt ready for a clinical test.

On January 11, 1922, Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old diabetic who lay dying at the Toronto General Hospital, was given the first injection of insulin. However, the extract was so impure that Thompson suffered a severe allergic reaction, and further injections were canceled. Over the next 12 days, Collip worked day and night to improve the ox-pancreas extract, and a second dose injected on the 23rd. This was completely successful, not only in not having obvious side-effects, but in completely eliminating the glycosuria sign of diabetes.

Children dying from diabetic keto-acidosis were kept in large wards, often with 50 or more patients in a ward, mostly comatose. Grieving family members were often in attendance, awaiting the (until then, inevitable) death. In one of medicine's more dramatic moments Banting, Best and Collip went from bed to bed, injecting an entire ward with the new purified extract. Before they had reached the last dying child, the first few were awakening from their coma, to the joyous exclamations of their families.

However, Banting and Best never worked well with Collip, regarding him as something of an interloper, and Collip left the project soon after.

Over the spring of 1922, Best managed to improve his techniques to the point where large quantities of insulin could be extracted on demand, but the preparation remained impure. The drug firm Eli Lilly and Company had offered assistance not long after the first publications in 1921, and they took Lilly up on the offer in April. In November, Lilly made a major breakthrough, and were able to produce large quantities of purer insulin. Insulin was offered for sale shortly thereafter.

Nobel Prizes

The Nobel Prize committee in 1923 credited the practical extraction of insulin to a team at the University of Toronto and awarded the Nobel Prize to two men; Frederick Banting and J.J.R. Macleod. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1923 for the discovery of insulin. Banting, insulted that Best was not mentioned, shared his prize with Best, and Macleod immediately shared his with Collip. The patent for insulin was sold to the University of Toronto for one dollar.

The exact sequence of amino acids comprising the insulin molecule, the so-called primary structure, was determined by British molecular biologist Frederick Sanger. It was the first protein to have its sequence be determined. He was awarded the 1958 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work.

In 1969, after decades of work, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin determined the spatial conformation of the molecule, the so-called tertiary structure, by means of X-ray diffraction studies. She had been awarded a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964 for the development of crystallography.

Rosalyn Sussman Yalow received the 1977 Nobel Prize in Medicine for the development of the radioimmunoassay for insulin.

Structure and production

Within vertebrates, the similarity of insulins is very close. Bovine insulin differs from human in only three amino acid residues, and porcine insulin in one. Even insulin from some species of fish is similar enough to human to be effective in humans. The C-peptide of proinsulin (discussed later), however, is very divergent from species to species.

In mammals, insulin is synthesized in the pancreas within the beta cells (β-cells) of the islets of Langerhans. One to three million islets of Langerhans (pancreatic islets) form the endocrine part of the pancreas, which is primarily an exocrine gland. The endocrine portion only accounts for 2% of the total mass of the pancreas. Within the islets of Langerhans, beta cells constitute 60–80% of all the cells.

In beta cells, insulin is synthesized from the proinsulin precursor molecule by the action of proteolytic enzymes, known as prohormone convertases (PC1 and PC2), as well as the exoprotease carboxypeptidase E. These modifications of proinsulin remove the center portion of the molecule, or C-peptide, from the C- and N- terminal ends of the proinsulin. The remaining polypeptides (51 amino acids in total), the B- and A- chains, are bound together by disulfide bonds. Confusingly, the primary sequence of proinsulin goes in the order "B-C-A", since B and A chains were identified on the basis of mass, and the C peptide was discovered after the others.

Actions on cellular and metabolic level

The actions of insulin on the global human metabolism level include:

- Control of cellular intake of certain substances, most prominently glucose in muscle and adipose tissue (about ⅔ of body cells).

- Increase of DNA replication and protein synthesis via control of amino acid uptake.

- Modification of the activity of numerous enzymes (allosteric effect).

The actions of insulin on cells include:

- Increased glycogen synthesis – insulin forces storage of glucose in liver (and muscle) cells in the form of glycogen; lowered levels of insulin cause liver cells to convert glycogen to glucose and excrete it into the blood. This is the clinical action of insulin which is directly useful in reducing high blood glucose levels as in diabetes.

- Increased fatty acid synthesis – insulin forces fat cells to take in blood lipids which are converted to triglycerides; lack of insulin causes the reverse.

- Increased esterification of fatty acids – forces adipose tissue to make fats (i.e., triglycerides) from fatty acid esters; lack of insulin causes the reverse.

- Decreased proteinolysis – forces reduction of protein degradation; lack of insulin increases protein degradation.

- Decreased lipolysis – forces reduction in conversion of fat cell lipid stores into blood fatty acids; lack of insulin causes the reverse.

- Decreased gluconeogenesis – decreases production of glucose from non-sugar substrates, primarily in the liver (remember, the vast majority of endogenous insulin arriving at the liver never leaves the liver) ; lack of insulin causes glucose production from assorted substrates in the liver and elsewhere.

- Increased amino acid uptake – forces cells to absorb circulating amino acids; lack of insulin inhibits absorption.

- Increased potassium uptake – forces cells to absorb serum potassium; lack of insulin inhibits absorption.

- Arterial muscle tone – forces arterial wall muscle to relax, increasing blood flow, especially in micro arteries; lack of insulin reduces flow by allowing these muscles to contract.

Regulatory action on blood glucose

Despite long intervals between meals or the occasional consumption of meals with a substantial carbohydrate load (e.g., half a birthday cake or a bag of potato chips or crisps if you're British), human blood glucose levels normally remain within a narrow range. In most humans this varies from about 70 mg/dl to perhaps 110 mg/dl (3.9 to 6.1 mmol/litre) except shortly after eating when the blood glucose level rises temporarily. This homeostatic effect is the result of many factors, of which hormone regulation is the most important.

It is usually a surprise to realize how little glucose is actually maintained in the blood and body fluids. The control mechanism works on very small quantities. In a healthy adult male of 75 kg with a blood volume of 5 litres, a blood glucose level of 100 mg/dl or 5.5 mmol/l corresponds to about 5 g (1/5 ounce) of glucose in the blood and approximately 45 g (1½ ounces) in the total body water (which obviously includes more than merely blood and will be usually about 60% of the total body weight in men). A more familiar comparison may help – 5 grams of glucose is about equivalent to a commercial sugar packet (as provided in many restaurants with coffee or tea).

There are two types of mutually antagonistic metabolic hormones affecting blood glucose levels:

- catabolic hormones (such as glucagon, growth hormone, and catecholamines), which increase blood glucose

- and one anabolic hormone (insulin), which decreases blood glucose

Mechanisms which restore satisfactory blood glucose levels after hypoglycemia must be quick and effective, because of the immediate serious consequences of insufficient glucose (in the extreme, coma, less immediately dangerously, confusion or unsteadiness, amongst many other effects). This is because, at least in the short term, it is far more dangerous to have too little glucose in the blood than too much. In healthy individuals these mechanisms are indeed generally efficient, and symptomatic hypoglycemia is generally only found in diabetics using insulin or other pharmacologic treatment. Such hypoglycemic episodes vary greatly between persons and from time to time, both in severity and swiftness of onset. In severe cases prompt medical assistance is essential, as damage (to brain and other tissues) and even death will result from sufficiently low blood glucose levels.

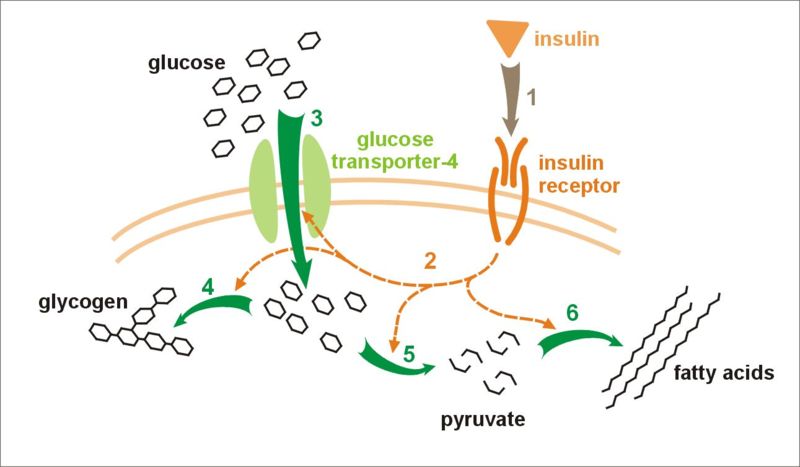

Beta cells in the islets of Langerhans are sensitive to variations in blood glucose levels through the following mechanism (see figure to the right):

- Glucose enters the beta cells through the glucose transporter GLUT2

- Glucose goes into the glycolysis and the respiratory cycle where multiple high-energy ATP molecules are produced by oxidation

- Dependent on ATP levels, and hence blood glucose levels, the ATP-controlled potassium channels (K+) close and the cell membrane depolarizes

- On depolarisation, voltage controlled calcium channels (Ca2+) open and calcium flows into the cells

- An increased calcium level causes activation of phospholipase C, which cleaves the membrane phospholipid phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate into inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerol.

- Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) binds to receptor proteins in the membrane of endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This allows the release of Ca2+ from the ER via IP3 gated channels, and further raises the cell concentration of calcium.

- Significantly increased amounts of calcium in the cells causes release of previously synthesised insulin, which has been stored in secretory vesicles

This is the main mechanism for release of insulin and regulation of insulin synthesis. In addition some insulin synthesis and release takes place generally at food intake, not just glucose or carbohydrate intake, and the beta cells are also somewhat influenced by the autonomic nervous system. The signalling mechanisms controlling this are not fully understood.

Other substances known which stimulate insulin release are acetylcholine, released from vagus nerve endings (parasympathetic nervous system), cholecystokinin, released by enteroendocrine cells of intestinal mucosa and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP). The first of these acts similarly to glucose through phospholipase C, while the last acts through the mechanism of adenylate cyclase.

The sympathetic nervous system (via α2-adrenergic agonists such as norepinephrine) inhibits the release of insulin.

When the glucose level comes down to the usual physiologic value, insulin release from the beta cells slows or stops. If blood glucose levels drop lower than this, especially to dangerously low levels, release of hyperglycemic hormones (most prominently glucagon from Islet of Langerhans' alpha cells) forces release of glucose into the blood from cellular stores, primarily liver cell stores of glycogen. By increasing blood glucose, the hyperglycemic hormones correct life-threatening hypoglycemia. Release of insulin is strongly inhibited by the stress hormone norepinephrine (noradrenaline), which leads to increased blood glucose levels during stress.

Signal transduction

There are special transporter proteins in cell membranes through which glucose from the blood can enter a cell. These transporters are, indirectly, under insulin control in certain body cell types (e.g., muscle cells). Low levels of circulating insulin, or its absence, will prevent glucose from entering those cells (e.g., in untreated Type 1 diabetes). However, more commonly there is a decrease in the sensitivity of cells to insulin (e.g., the reduced insulin sensitivity characteristic of Type 2 diabetes), resulting in decreased glucose absorption. In either case, there is 'cell starvation', weight loss, sometimes extreme. In a few cases, there is a defect in the release of insulin from the pancreas. Either way, the effect is, characteristically, the same: elevated blood glucose levels.

Activation of insulin receptors leads to internal cellular mechanisms that directly affect glucose uptake by regulating the number and operation of protein molecules in the cell membrane that transport glucose into the cell. The genes that specify the proteins that make up the insulin receptor in cell membranes have been identified and the structure of the interior, cell membrane section, and now, finally after more than a decade, the extra-membrane structure of receptor (Australian researchers announced the work 2Q 2006).

Two types of tissues are most strongly influenced by insulin, as far as the stimulation of glucose uptake is concerned: muscle cells (myocytes) and fat cells (adipocytes). The former are important because of their central role in movement, breathing, circulation, etc, and the latter because they accumulate excess food energy against future needs. Together, they account for about two-thirds of all cells in a typical human body.

Insulin degradation

Once an insulin molecule has docked onto the receptor and effected its action, it may be released back into the extracellular environment or it may be degraded by the cell. Degradation normally involves endocytosis of the insulin-receptor complex followed by the action of insulin degrading enzyme. Most insulin molecules are degraded by liver cells. It has been estimated that a typical insulin molecule that is produced endogenously by the pancreatic beta cells is finally degraded about 71 minutes after its initial release into circulation.[2]

Hypoglycemia

Although other cells can use other fuels for a while (most prominently fatty acids), neurons depend on glucose as a source of energy in the non-starving human. They do not require insulin to absorb glucose, unlike muscle and adipose tissue, and they have very small internal stores of glycogen. Glycogen stored in liver cells (unlike glycogen stored in muscle cells) can be converted to glucose, and released into the blood, when glucose from digestion is low or absent, and the glycerol backbone in triglycerides can also be used to produce blood glucose.

Exhaustion of these sources can, either temporarily or on a sustained basis, if reducing blood glucose to a sufficiently low level, first and most dramatically manifest itself in impaired functioning of the central nervous system – dizziness, speech problems, even loss of consciousness, are not unknown. This is known as hypoglycemia or, in cases producing unconsciousness, "hypoglycemic coma" (formerly termed "insulin shock" from the most common causative agent). Endogenous causes of insulin excess (such as an insulinoma) are very rare, and the overwhelming majority of hypoglycemia cases are caused by human action (e.g., iatrogenic, caused by medicine) and are usually accidental. There have been a few reported cases of murder, attempted murder, or suicide using insulin overdoses, but most insulin shocks appear to be due to errors in dosage of insulin (e.g., 20 units of insulin instead of 2) or other unanticipated factors (didn't eat as much as anticipated, or exercised more than expected).

Possible causes of hypoglycemia include:

- External insulin (usually injected subcutaneously).

- Oral hypoglycemic agents (e.g., any of the sulfonylureas, or similar drugs, which increase insulin release from beta cells in response to a particular blood glucose level).

- Ingestion of low-carbohydrate sugar substitutes (animal studies show these can trigger insulin release (albeit in much smaller quantities than sugar) according to a report in Discover magazine, August 2005, p18).

Diseases and syndromes

There are several conditions in which insulin disturbance is pathologic:

- Diabetes mellitus – general term referring to all states characterized by hyperglycemia.

- Type 1 – autoimmune-mediated destruction of insulin producing beta cells in the pancreas resulting in absolute insulin deficiency.

- Type 2 – multifactoral syndrome with combined influence of genetic susceptibility and influence of environmental factors, the best known being obesity, age, and physical inactivity, resulting in insulin resistance in cells requiring insulin for glucose absorption. This form of diabetes is strongly inherited.

- Other types of impaired glucose tolerance (see the diabetes article).

- Insulinoma or reactive hypoglycemia.

- Metabolic syndrome – a poorly understood condition first called Syndrome X by Gerald Reaven, Reaven's Syndrome after Reaven, CHAOS in Australia (from the signs which seem to travel together), and sometimes prediabetes. It is currently not clear whether these signs have a single, treatable cause, or are the result of body changes leading to type 2 diabetes. It is characterized by elevated blood pressure, dyslipidemia (disturbances in blood cholesterol forms and other blood lipids), and increased waist circumference (at least in populations in much of the developed world). The basic underlying cause may be the insulin resistance of type 2 diabetes which is a diminished capacity for insulin response in some tissues (e.g., muscle, fat) to respond to insulin. Commonly, morbidities such as essential hypertension, obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) develop.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome – a complex syndrome in women in the reproductive years where there is anovulation and androgen excess commonly displayed as hirsutism. In many cases of PCOS insulin resistance is present.

As a medication

Principles

Insulin is required for all animal (including human) life. Its mechanism of action is almost identical in nematode worms (e.g. C. elegans), fish, and mammals, and it is a protein that has been highly conserved throughout evolution. In humans, insulin deprivation due to the removal or destruction of the pancreas leads to death in days or, at most, weeks. Insulin must be administered to patients who experience such a deprivation. Clinically, this condition is called diabetes mellitus type 1.

The initial sources of insulin for clinical use in humans were cow, horse, pig or fish pancreases. Insulin from these sources is effective in humans as it is nearly identical to human insulin (three amino acid difference in bovine insulin, one amino acid difference in porcine). Differences in suitability of beef, pork, or fish derived insulin for individual patients have been primarily due to low preparation purity resulting in allergic reactions to the presence of non-insulin substances. Though purity has improved steadily since the 1920s, less severe allergic reactions still occur occasionally. Insulin production from animal pancreases was widespread for decades, but very few patients today rely on insulin from animal sources, largely because few pharmaceutical companies sell it anymore.

Synthetic "human" insulin is now manufactured for widespread clinical use using genetic engineering techniques, which significantly reduces the presence of impurities. Eli Lilly marketed the first such insulin, Humulin, in 1982. Humulin was the first medication produced using modern genetic engineering techniques in which actual human DNA is inserted into a host cell (E. coli in this case). The host cells are then allowed to grow and reproduce normally, and due to the inserted human DNA, they produce a synthetic version of human insulin.

Genentech developed the technique Lilly used to produce Humulin. Novo Nordisk has also developed a genetically engineered insulin independently. Most insulins used clinically today are produced this way, as they are usually less likely to produce an allergic reaction, although clinical evidence has provided only mixed evidence of this claim.

Since January 2006, all insulins distributed in the U.S. and some other countries are human insulins or their analogs. A special FDA importation process is required to obtain bovine or porcine derived insulin for use in the U.S., though there may be some remaining stocks of porcine insulin made by Lilly in 2005 or earlier.

There are several problems with insulin as a clinical treatment for diabetes:

- Mode of administration.

- Selecting the 'right' dose and timing.

- Selecting an appropriate insulin preparation (typically on 'speed of onset and duration of action' grounds).

- Adjusting dosage and timing to fit food intake timing, amounts, and types.

- Adjusting dosage and timing to fit exercise undertaken.

- Adjusting dosage, type, and timing to fit other conditions, for instance the increased stress of illness.

- The dosage is non-physiological in that a subcutaneous bolus dose of insulin alone is administered instead of combination of insulin and C-peptide being released gradually and directly into the portal vein.

- It is simply a nuisance for patients to inject whenever they eat carbohydrate or have a high blood glucose reading.

- It is dangerous in case of mistake (most especially 'too much' insulin).

Types

Medical preparations of insulin (from the major suppliers – Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis – or from any other) are never just 'insulin in water'. Clinical insulins are specially prepared mixtures of insulin plus other substances. These delay absorption of the insulin, adjust the pH of the solution to reduce reactions at the injection site, and so on.

Slight variations of the human insulin molecule are called insulin analogs. They have absorption and activity characteristics not possible with subcutaneously injected insulin proper. They are either absorbed rapidly enough in an effort to mimic real beta cell insulin (as with Lilly's lispro, Novo Nordisk's aspart and Sanofi Aventis' glulisine), or steadily absorbed after injection instead of having a 'peak' followed by a more or less rapid decline in insulin action (as with Novo Nordisk's version Insulin detemir and Sanofi Aventis's Insulin glargine), all while retaining insulin action in the human body.

Choosing insulin type and dosage / timing should be done by an experienced medical professional working with the diabetic patient.

The commonly used types of insulin are:

- Rapid-acting, are presently insulin analogs, such as the insulin analog lispro – begins to work within 5 to 15 minutes and is active for 3 to 4 hours.

- Short-acting, such as regular insulin – starts working within 30 minutes and is active about 5 to 8 hours.

- Intermediate-acting, such as NPH, or lente insulin – starts working in 1 to 3 hours and is active 16 to 24 hours.

- Long-acting, such as ultralente insulin – starts working in 4 to 6 hours, and is active 24 to 28 hours.

- Insulin glargine and Insulin detemir – both insulin analogs which start working within 1 to 2 hours and continue to be active, without major peaks or dips, for about 24 hours, although this varies in many individuals.

- A mixture of NPH and regular insulin – starts working in 30 minutes and is active 16 to 24 hours. There are several variations with different proportions of the mixed insulins.

Modes of administration

Unlike many medicines, insulin cannot be taken orally. Like nearly all other proteins introduced into the gastrointestinal tract, it is reduced to fragments (even single amino acid components), whereupon all 'insulin activity' is lost.

Subcutaneous

Insulin is usually taken as subcutaneous injections by single-use syringes with needles, an insulin pump, or by repeated-use insulin pens with needles.

Insulin pump

Insulin pumps are a reasonable solution for some. Advantages to the patient are better control over background or 'basal' insulin dosage, bolus doses calculated to fractions of a unit, and calculators in the pump that may help with determining 'bolus' infusion doages. The limitations are cost, the potential for hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic episodes, catheter problems, and no "closed loop" means of controlling insulin delivery based on current blood glucose levels.

Insulin pumps may be like 'electrical injectors' attached to a semi-permanently implanted catheter or cannula. Some who cannot achieve adequate glucose control by conventional (or jet) injection are able to do so with the appropriate pump.

As with injections, if too much insulin is delivered or the patient eats less than he or she dosed for, there will be hypoglycemia. On the other hand, if too little insulin is delivered, there will be hyperglycemia. Both can be life-threatening. In addition, indwelling catheters pose the risk of infection and ulceration, and some patients may also develop lipodystrophy due to the infusion sets. These risks can often be minimized by keeping infusion sites clean. Insulin pumps require care and effort to use correctly. However, some patients with diabetes are capable of keeping their glucose in reasonable control only with an insulin pump.

Inhalation

In 2006 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of Exubera, the first inhalable insulin.[3] Inhaled insulin has similar efficacy to injected insulin, both in terms of controlling glucose levels and blood half-life. Currently, inhaled insulin is short acting and is typically taken before meals; an injection of long-acting insulin at night is often still required.[4] When patients were switched from injected to inhaled insulin, no significant difference was found in HbA1c levels over three months. Accurate dosing is still a problem, but patients showed no significant weight gain or pulmonary function decline over the length of the trial, when compared to the baseline.[5] Following its commercial launch in 2005 in the UK, it has not (as of July 2006) been recommended by National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence for routine use, except in cases where there is "proven injection phobia diagnosed by a psychiatrist or psychologist".[4]

Transdermal

There are several methods for transdermal delivery of insulin. Pulsatile insulin uses microjets to pulse insulin into the patient, mimicking the physiological secretions of insulin by the pancreas.[6] Jet injection (also sometimes used for vaccinations) had different insulin delivery peaks and durations as compared to needle injection. Some diabetics find control possible with jet injectors, but not with hypodermic injection.

Both electricity using iontophoresis[7] and ultrasound have been found to make the skin temporarily porous. The insulin administration aspect remains experimental, but the blood glucose test aspect of 'wrist appliances' is commercially available.

Researchers have produced a watch-like device that tests for blood glucose levels through the skin and administers corrective doses of insulin through pores in the skin.

Intranasal insulin

Intranasal insulin is being investigated.[8]

Oral insulin

The basic appeal of oral hypoglycemic agents is that most people would prefer a pill to an injection. However, insulin is a protein. Protein hormones, like meat proteins, are digested in the stomach and gut.

The potential market for an oral form of insulin is assumed to be enormous, thus many laboratories have attempted to devise ways of moving enough intact insulin from the gut to the portal vein to have a measurable effect on blood sugar. One can find several research reports over the years describing promising approaches or limited success in animals, and limited human testing, but as of 2004, no products appear to be successful enough to bring to market.[9]

Pancreatic transplantation

Another improvement would be a transplantation of the pancreas or beta cell to avoid periodic insulin administration. This would result in a self-regulating insulin source. Transplantation of an entire pancreas (as an individual organ) is difficult and relatively uncommon. It is often performed in conjunction with liver or kidney transplant, although it can be done by itself. It is also possible to do a transplantation of only the pancreatic beta cells. It has been highly experimental (for which read 'prone to failure') for many years, but some researchers in Alberta, Canada, have developed techniques with a high initial success rate (about 90% in one group). Nearly half of those who got an islet cell transplant are insulin-free one year after the operation; by the end of the second year that number drops to about one in seven. Beta cell transplant may become practical in the near future. Additionally, some researchers have explored the possibility of transplanting genetically engineered non-beta cells to secrete insulin.[10] Clinically testable results are far from realization at this time. Several other non-transplant methods of automatic insulin delivery are being developed in research labs, but none is close to clinical approval.

Artificial pancreas

Dosage and timing

The central problem for those requiring external insulin is picking the right dose of insulin and the right timing.

Physiological regulation of blood glucose, as in the non-diabetic, would be best. Increased blood glucose levels after a meal is a stimulus for prompt release of insulin from the pancreas. The increased insulin level causes glucose absorption and storage in cells, reducing glycogen to glucose conversion, reducing blood glucose levels, and so reducing insulin release. The result is that the blood glucose level rises somewhat after eating, and within an hour or so, returns to the normal 'fasting' level. Even the best diabetic treatment with synthetic human insulin, however administered, falls far short of normal glucose control in the non-diabetic.

Complicating matters is that the composition of the food eaten (see glycemic index) affects intestinal absorption rates. Glucose from some foods is absorbed more (or less) rapidly than the same amount of glucose in other foods. Fats and proteins cause delays in absorption of glucose from carbohydrate eaten at the same time. As well, exercise reduces the need for insulin even when all other factors remain the same, since working muscle has some ability to take up glucose without the help of insulin.

It is, in principle, impossible to know for certain how much insulin (and which type) is needed to 'cover' a particular meal to achieve a reasonable blood glucose level within an hour or two after eating. Non-diabetics' beta cells routinely and automatically manage this by continual glucose level monitoring and insulin release. All such decisions by a diabetic must be based on experience and training (i.e., at the direction of a physician, PA, or in some places a specialist diabetic educator) and, further, specifically based on the individual experience of the patient. But it is not straightforward and should never be done by habit or routine. With care however, it can be done quite successfully in clinical practice.

For example, some diabetics require more insulin after drinking skim milk than they do after taking an equivalent amount of fat, protein, carbohydrate, and fluid in some other form. Their particular reaction to skimmed milk is different from other people with diabetes, but the same amount of whole milk is likely to cause a still different reaction even in that person. Whole milk contains considerable fat while skimmed milk has much less. It is a continual balancing act for all people with diabetes, especially for those taking insulin.

Patients with insulin-dependent diabetes require some base level of insulin (basal insulin), as well as short-acting insulin to cover meals (bolus insulin). Maintaining the basal rate and the bolus rate is a continuous balancing act that people with insulin-dependent diabetes must manage each day. This is normally achieved through regular blood tests, although there is work being done on continuous blood sugar testing equipment.

It is important to notice that patients with diabetes generally need more insulin than the usual – not less – during physical stress like infections or surgeries.

Abuse

There are reports that some patients abuse insulin by injecting large doses that lead to hypoglycemic states. This is extremely dangerous. Severe acute or prolonged hypoglycemia can result in brain damage or death.

On July 23, 2004, news reports claimed that a former spouse of a prominent international track athlete said that, among other drugs, the ex-spouse had used insulin as a way of 'energizing' the body. The intended implication would seem to be that insulin has effects similar to those alleged for some steroids. This is not so: 80 years of injected insulin use has given no reason to believe it could be in any respect a performance enhancer for non-diabetics. Improperly treated diabetics are, to be sure, more prone than others to exhaustion and tiredness, and in some cases, proper administration of insulin can relieve such symptoms. Insulin is not, chemically or clinically, a steroid, and its use in non-diabetics is dangerous and always an abuse outside of a well-equipped medical facility.

"Game of Shadows," by reporters Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams, includes allegations that San Francisco Giant, Barry Bonds, used insulin in the apparent belief that it would increase the effectiveness of the growth hormone he was (also alleged to be) taking. On top of this, non-prescribed insulin is a banned drug at the Olympics and other global competitions.

The use and abuse of exogenous insulin is widespread amongst the bodybuilding community. Both insulin, growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) are self-administered by those looking to increase muscle mass beyond the scope offered by anabolic steroids alone. Their rationale is this: Since insulin and GH act synergistically to promote growth, and since IGF1 is the primary mediator of the musculoskeletal effects of growth hormone, the 'stacking' of insulin, GH and IGF1 should offer a synergistic growth effect on skeletal muscle. This theory has been borne out in recent years by the creation of top-level bodybuilders whose competition weight is in excess of 50lbs of muscle greater than the professionals of the past, yet with even lower levels of body fat. Indeed, the use of insulin, combined with GH and/or IGF1 has resulted in the development of such massively muscled physiques, that there has been a backlash amongst fans of the sport, with a professed disgust at the 'freakish' appearance of top-level professionals.

Bodybuilders will inject up to 10 i.u. of quick-acting synthetic insulin following meals containing starchy carbohydrates and protein, but little fat, in an attempt to 'force feed' nutrients necessary for growth into skeletal muscle, whilst preventing growth of adipocytes. This may be done up to 4 times each day, following meals, for a total usage of 40iu of synthetic insulin per day. However there have been reports of substantially heavier usage, amongst even 'recreational' bodybuilders.

The abuse of exogenous insulin carries with it an attendant risk of hypoglycemic coma and death. Long term risks include development of type II diabetes, and a lifetime dependency on synthetic insulin.

Timeline of insulin research

- 1922 Banting, Best, Collip use bovine insulin extract in human

- 1923 Eli Lilly produces commercial quantities of much purer bovine insulin than Banting et al had used

- 1923 Hagedorn founds the Nordisk Insulinlaboratorium in Denmark – forerunner of Novo Nordisk

- 1926 Nordisk receives a Danish charter to produce insulin as a non profit

- 1936 Canadians D.M. Scott, A.M. Fisher formulate a zinc insulin mixture and license it to Novo

- 1936 Hagedorn discovers that adding protamine to insulin prolongs the duration of action of insulin

- 1946 Nordisk formulates Isophane porcine insulin aka Neutral Protamine Hagedorn or NPH insulin

- 1946 Nordisk crystallizes a protamine and insulin mixture

- 1950 Nordisk markets NPH insulin

- 1953 Novo formulates Lente porcine and bovine insulins by adding zinc for longer lasting insulin

- 1955 Frederick Sanger determines the amino acid sequence of insulin

- 1969 Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin solves the crystal structure of insulin by x-ray crystallography

- 1973 Purified monocomponent (MC) insulin is introduced

- 1978 Genentech produces human insulin in Escheria coli bacteria using recombinant DNA techniques, licenses to Eli Lilly

- 1981 Novo Nordisk chemically and enzymatically converts bovine to human insulin

- 1982 Genentech human insulin (above) approved

- 1983 Eli Lilly produces recombinant human insulin, Humulin

- 1985 Axel Ullrich sequences a human cell membrane insulin receptor

- 1988 Novo Nordisk produces recombinant human insulin

- 1996 Lilly Humalog "lyspro" insulin analogue approved

- 2004 Aventis Lantus "glargine" insulin analogue approved for clinical use[citation needed]

- 2006 Novo Nordisk Levemir "detemir" insulin analogue approved for clinical use in the US.

See also

- Insulin analog

- Anatomy and physiolology

- Forms of diabetes mellitus

- Treatment

- Other medical / diagnostic uses

References

- Reaven, Gerald M. (1999--04-15). Insulin Resistance: The Metabolic Syndrome X (1st Edition ed.). Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press. doi:10.1226/0896035883. ISBN 0-89603-588-3. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Leahy, Jack L. (2002-03-22). Insulin Therapy (1st Edtition ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-0711-7. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - Kumar, Sudhesh (2005-01-14). Insulin Resistance: Insulin Action and Its Disturbances in Disease. Chichester, England: Wiley. ISBN 0-470-85008-6. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - Ehrlich, Ann (2000-06-16). Medical Terminology for Health Professions (4th Edition ed.). Thomson Delmar Learning. ISBN 0-7668-1297-9. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - Draznin, Boris (1994). Molecular Biology of Diabetes: Autoimmunity and Genetics; Insulin Synthesis and Secretion. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press. doi:10.1226/0896032868. ISBN 0-89603-286-8. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - Famous Canadian Physicians: Sir Frederick Banting at Library and Archives Canada

Footnotes

- ↑ Ian Murray (1971). "Paulesco and the Isolation of Insulin" (PDF). Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 26 (2): 150–157.

- ↑ William C. Duckworth, Robert G. Bennett and Frederick G. Hamel (1998). "Insulin Degradation: Progress and Potential". Endocrine Reviews. 19 (5): 608–624.

- ↑ FDA approval of Exubera inhaled insulin

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 NICE (2006). "Diabetes (type 1 and 2), Inhaled Insulin - Appraisal Consultation Document (second)". Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Cefalu W, Skyler J, Kourides I, Landschulz W, Balagtas C, Cheng S, Gelfand R (2001). "Inhaled human insulin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus". Ann Intern Med. 134 (3): 203–7. PMID 11177333.

- ↑ Arora A, Hakim I, Baxter J; et al. (2007). "Needle-free delivery of macromolecules across the skin by nanoliter-volume pulsed microjets". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (11): 4255–60. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700182104. PMID 17360511.

- ↑ Dixit N, Bali V, Baboota S, Ahuja A, Ali J (2007). "Iontophoresis - an approach for controlled drug delivery: a review". Current drug delivery. 4 (1): 1–10. PMID 17269912.

- ↑ Lalej-Bennis D, Boillot J, Bardin C; et al. (2001). "Efficacy and tolerance of intranasal insulin administered during 4 months in severely hyperglycaemic Type 2 diabetic patients with oral drug failure: a cross-over study". Diabet. Med. 18 (8): 614–8. PMID 11553197.

- ↑ "Oral Insulin - Fact or Fiction? - Resonance - May 2003".

- ↑ Yong Lian Zhu; et al. (2003). "Aggregation and Lack of Secretion of Most Newly Synthesized Proinsulin in Non-ß-Cell Lines". Endocrinology. 145 (8): 3840–3849.

External links

- The Insulin Protein

- Comparison chart of insulin types use to treat diabetes.

- Inspired by Insulin article by parent of a diabetic child

- Frederick Sanger, Nobel Prize for sequencing Insulin Freeview video with John Sanger and John Walker by the Vega Science Trust.

- Insulin: entry from protein databank

- The History of Insulin

- Insulin Lispro

- CBC Digital Archives - Banting, Best, Macleod, Collip: Chasing a Cure for Diabetes

- Cosmos Magazine: Insulin mystery cracked after 20 years

- National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse

- Discovery and Early Development of Insulin, 1920-1925

af:Insulien ar:أنسولين ast:Insulina bs:Inzulin bg:Инсулин ca:Insulina cs:Inzulín da:Insulin de:Insulin dv:އިންސިޔުލިން et:Insuliin el:Ινσουλίνη eo:Insulino gl:Insulina ko:인슐린 hr:Inzulin id:Insulin is:Insúlín it:Insulina he:אינסולין ku:Însulîn lv:Insulīns lt:Insulinas hu:Inzulin ml:ഇന്സുലിന് ms:Insulin nl:Insuline no:Insulin nn:Insulin sq:Insulina simple:Insulin sk:Inzulín sl:Insulin sr:Инсулин su:Insulin fi:Insuliini sv:Insulin uk:Інсулін yi:אינסאלין

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2007

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- CS1 errors: dates

- CS1 maint: Extra text

- Lilly

- Recombinant proteins

- Peptide hormones

- Pancreatic hormones

- Insulin therapies

- Diabetes

- Endocrinology