Congenital heart disease

| Congenital heart disease | ||

| ||

|---|---|---|

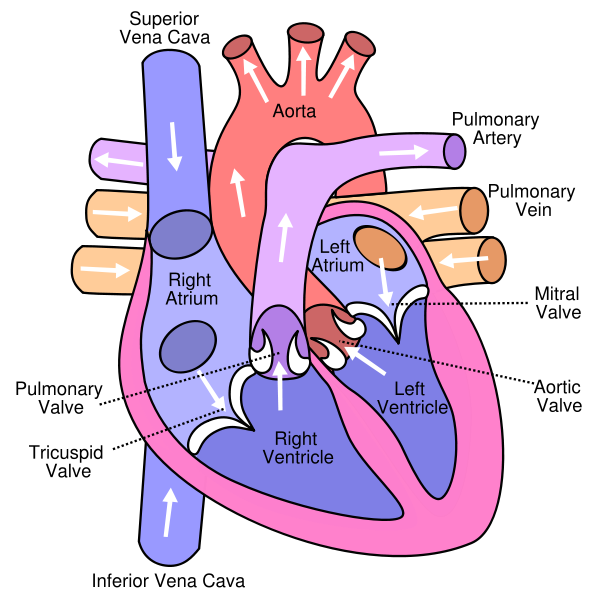

| Cross-section diagram of a normal human heart | ||

| ICD-10 | I01.0, I09.2, I30-I32 | |

| ICD-9 | 420.90 | |

| DiseasesDB | 9820 | |

| MedlinePlus | 000182 | |

| eMedicine | med/1781 emerg/412 | |

| MeSH | heart disease&field=entry#TreeC14.280.720 C14.280.720 | |

|

Congenital heart disease Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Congenital heart disease from other Disorders |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Congenital heart disease On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Congenital heart disease |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Congenital heart disease |

For patient information click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editors-In-Chief: Keri Shafer, M.D. [2]; Atif Mohammad, M.D.

Overview

Causes

Differential diagnosis

Congenital heart disease classification

Congenital heart disease septal |Congenital heart disease obstructive|Congenital heart disease cyanotic

Obstruction defects

Obstruction defects occur when heart valves, arteries, or veins are abnormally narrow or blocked. Common obstruction defects include pulmonary valve stenosis, aortic valve stenosis, and coarctation of the aorta, with other types such as bicuspid aortic valve stenosis and subaortic stenosis being comparatively rare. Any narrowing or blockage can cause heart enlargement or hypertension.

Cyanotic defects

Cyanotic heart defects are called such because they result in cyanosis, a bluish-grey discoloration of the skin due to a lack of oxygen in the body. Such defects include persistent truncus arteriosus, total anomalous pulmonary venous connection, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition of the great vessels, and tricuspid atresia.

Antenatal Detection and Diagnosis

Before birth, an obstetric ultrasound scan may be used to screen pregnant women for signs of CHD in their unborn babies. This screening scan is often performed around 20 weeks of pregnancy when the fast moving structures of the fetal heart are large enough to be more easily imaged. If CHD is suspected, a mother will be referred for a fetal echocardiograph, which is a more detailed, diagnostic ultrasound scan by a specialist cardiologist. It is increasingly possible for specialists to screen for CHD as early as 14 weeks, if CHD is suspected from other factors, such as a family history.

Postnatal Detection and Diagnosis

After delivery, if congenital heart disease is present but has not been detected, then a newborn baby may appear blue or breathless. Signs of CHD are sometimes mistaken for an infection or illness, so it is important to rule this out. Blueness and/or breathlessness may take some time to present, depending on the type of congenital heart disease and whether there is a duct-dependent lesion (i.e. one relying on an open ductus arteriosis for blood flow). This duct usually closes within the first three days of life in babies born at term (i.e. at nine months gestation).

Detection and Diagnosis in Adulthood

Although the majority of congenital heart disease diagnoses are made in childhood, there are significant congenital heart defects which may be go undetected until adulthood. These typically include defects that do not cause cyanosis ("blueness") in childhood but may cause problems over time, such as certain kinds of valve problems, transposition disorders, holes in the heart, and abnormalities of the heart's major veins and arteries. Congenital heart defects are most commonly diagnosed through an echocardiogram - an ultrasound of the heart which shows the heart's structure. Cardiac magnetic resonance(MRI) are used to confirm CHD when signs or symptoms occur in the physical examination. An echocardiograph displays images of the might also be used to confirm the problem, particularly in complex defects in which anatomy is hard to determine with echocardiography. It also finds abnormal rhythms or defects of the heart present with CHD. A chest x-ray may also be issued to look at the anatomical position of the heart and lungs. A Cat Scan(CT) can also be used to visualize CHD. All of these tests are ways to diagnose CHD by a physician.

ACC / AHA Guidelines-Recommendations for Permanent Pacing in Children, Adolescents, and Patients With Congenital (DO NOT EDIT) [1]

| “ |

Class I1. Permanent pacemaker implantation is indicated for advanced second- or third-degree AV block associated with symptomatic bradycardia, ventricular dysfunction, or low cardiac output. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Permanent pacemaker implantation is indicated for SND with correlation of symptoms during age-inappropriate bradycardia. The definition of bradycardia varies with the patient’s age and expected heart rate. (Level of Evidence: B) 3. Permanent pacemaker implantation is indicated for postoperative advanced second- or third-degree AV block that is not expected to resolve or that persists at least 7 days after cardiac surgery. (Level of Evidence: B) 4. Permanent pacemaker implantation is indicated for congenital third-degree AV block with a wide QRS escape rhythm, complex ventricular ectopy, or ventricular dysfunction. (Level of Evidence: B) 5. Permanent pacemaker implantation is indicated for congenital third-degree AV block in the infant with a ventricular rate less than 55 bpm or with congenital heart disease and a ventricular rate less than 70 bpm. (Level of Evidence: C) Class IIa1. Permanent pacemaker implantation is reasonable for patients with congenital heart disease and sinus bradycardia for the prevention of recurrent episodes of intra-atrial reentrant tachycardia; SND may be intrinsic or secondary to antiarrhythmic treatment. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Permanent pacemaker implantation is reasonable for congenital third-degree AV block beyond the first year of life with an average heart rate less than 50 bpm, abrupt pauses in ventricular rate that are 2 or 3 times the basic cycle length, or associated with symptoms due to chronotropic incompetence. (Level of Evidence: B) 3. Permanent pacemaker implantation is reasonable for sinus bradycardia with complex congenital heart disease with a resting heart rate less than 40 bpm or pauses in ventricular rate longer than 3 seconds. (Level of Evidence: C) 4. Permanent pacemaker implantation is reasonable for patients with congenital heart disease and impaired hemodynamics due to sinus bradycardia or loss of AV synchrony. (Level of Evidence: C) 5. Permanent pacemaker implantation is reasonable for unexplained syncope in the patient with prior congenital heart surgery complicated by transient complete heart block with residual fascicular block after a careful evaluation to exclude other causes of syncope. (Level of Evidence: B) Class IIb1. Permanent pacemaker implantation may be considered for transient postoperative third-degree AV block that reverts to sinus rhythm with residual bifascicular block. (Level of Evidence: C) 2. Permanent pacemaker implantation may be considered for congenital third-degree AV block in asymptomatic children or adolescents with an acceptable rate, a narrow QRS complex, and normal ventricular function. (Level of Evidence: B) 3. Permanent pacemaker implantation may be considered for asymptomatic sinus bradycardia after biventricular repair of congenital heart disease with a resting heart rate less than 40 bpm or pauses in ventricular rate longer than 3 seconds. (Level of Evidence: C) Class III1. Permanent pacemaker implantation is not indicated for transient postoperative AV block with return of normal AV conduction in the otherwise asymptomatic patient. (Level of Evidence: B) 2. Permanent pacemaker implantation is not indicated for asymptomatic bifascicular block with or without first-degree AV block after surgery for congenital heart disease in the absence of prior transient complete AV block. (Level of Evidence: C) 3. Permanent pacemaker implantation is not indicated for asymptomatic type I second-degree AV block. (Level of Evidence: C) 4. Permanent pacemaker implantation is not indicated for asymptomatic sinus bradycardia with the longest relative risk interval less than 3 seconds and a minimum heart rate more than 40 bpm. (Level of Evidence: C) |

” |

Outcomes

It is now estimated that the number of adults in the United States who have congenital heart disease is approaching one million. Because of advances in cardiac surgery, many who would not previously have survived childhood, now lead normal or relatively normal lives. However, some increase in complications has been observed in adults who were previously thought to have had successful repair of heart defects. These complications include cardiac arrhythmia, disorders of heart valves, and heart failure. Regular check-ups by cardiologists are now recommended for patients with histories of congenital heart disease, including those who may have previously been told that their defects were successfully repaired. Since most adult cardiologists have little experience with congenital heart disease, congenital heart disease centers[3] have been developed to care for adult patients with more severe congenital heart disease. It is thought that some patients, especially those with more complex disorders, and women who are pregnant or considering pregnancy, would likely do better if they are followed in specialty centers. Guidelines have been developed regarding which patients may be successfully followed in non-specialized cardiology practices, and which should be seen in adult congenital heart disease centers.

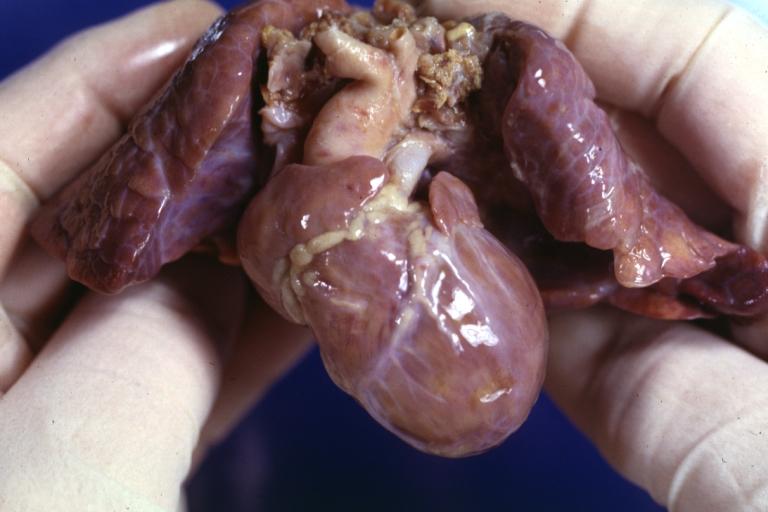

Pathological Findings

-

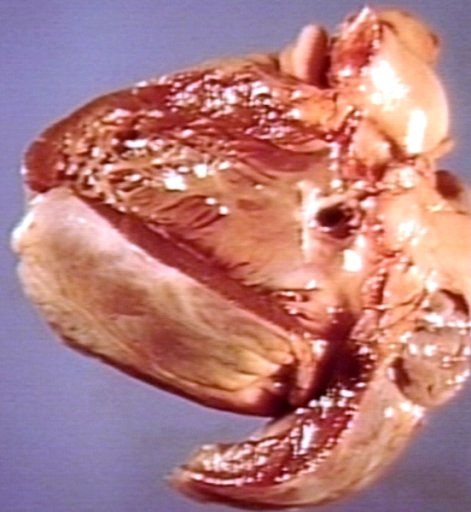

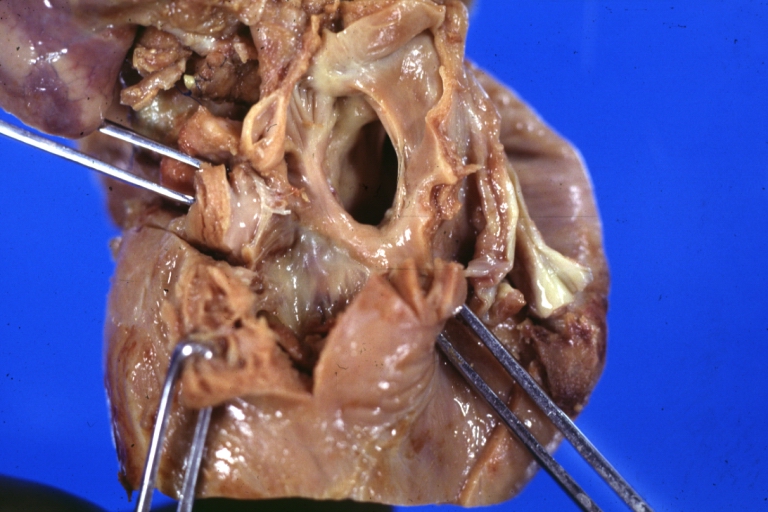

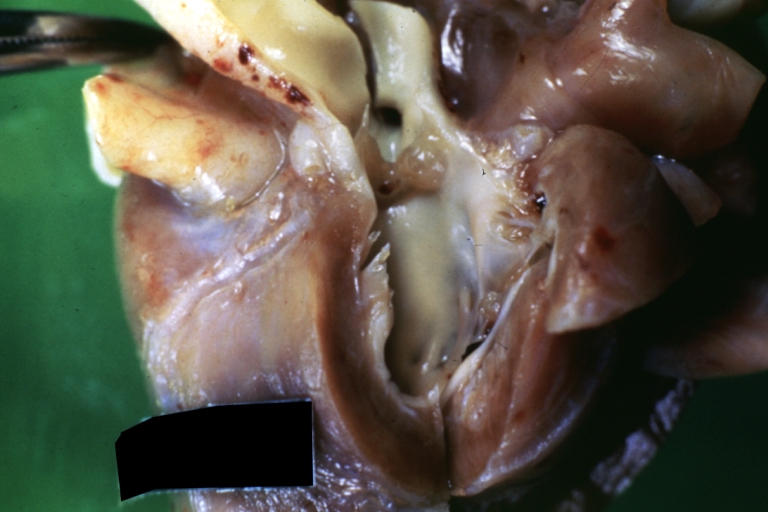

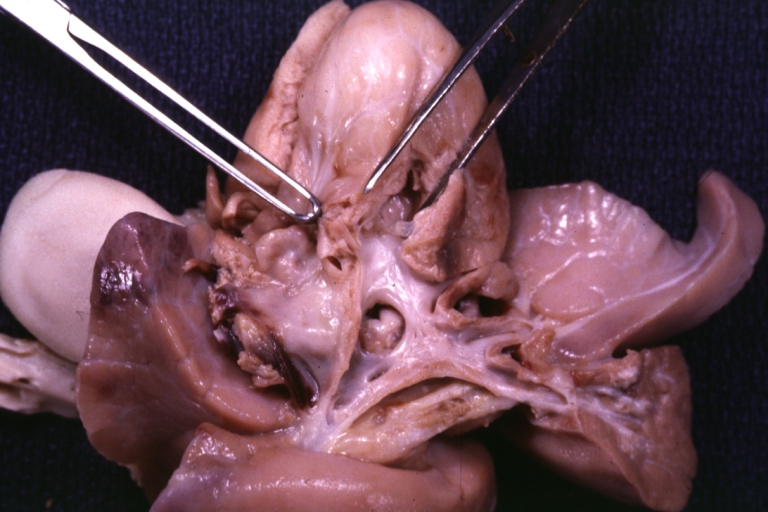

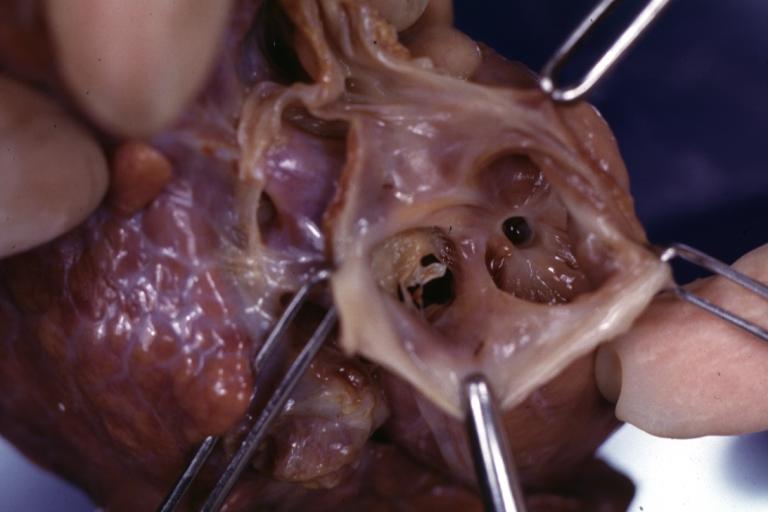

Right Ventricle Hypoplasia: Gross natural color good example showing tiny tricuspid inlet and very small but quite thick right ventricle

-

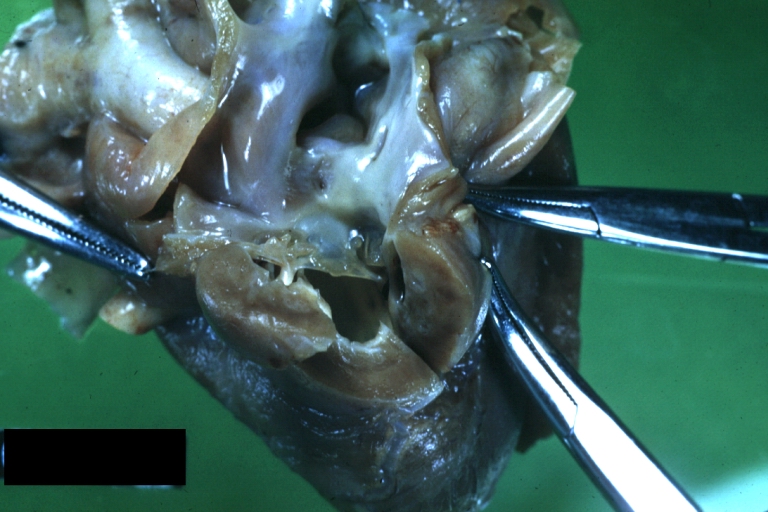

Right Ventricle Hypoplasia: Gross natural color view from right atrium showing patent foramen ovale and very small tricuspid valve

-

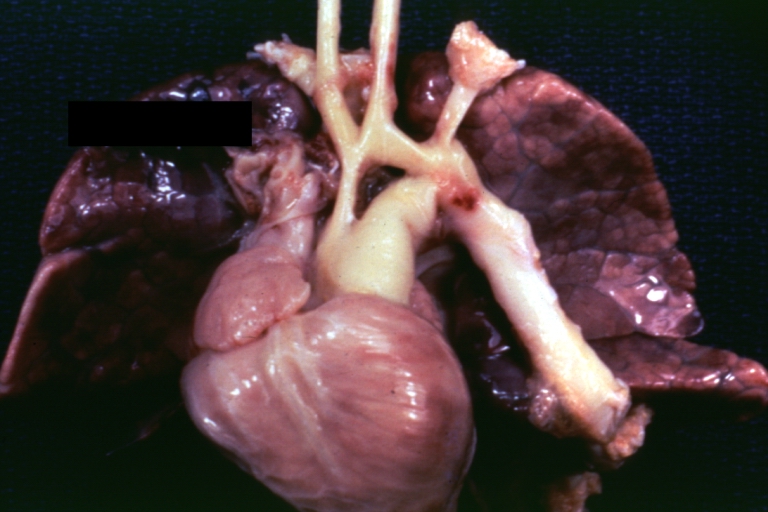

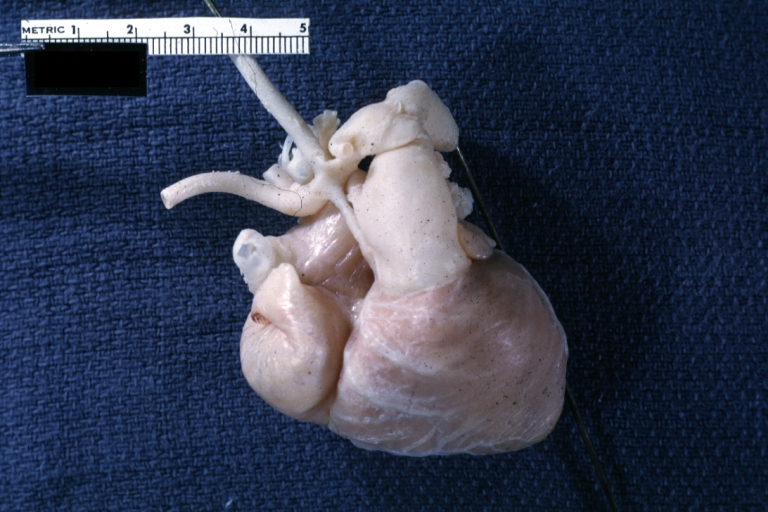

Right Ventricle Hypoplasia: Gross natural color external view of heart showing very large left ventricle and very small right ventricle delineated by anterior descending branch of left coronary artery

External links

- Cleveland Clinic Webchat - Adult Congenital Heart Disease Webchat with Dr. Richard Krasuski.

- Cleveland Clinic Webchat - Adult Congenital Heart Disease Surgery Webchat with Dr. Gosta Pettersson.

- It's My Heart Advocating for and Supporting those affected by Congenital Heart Defects - US Non-Profit under section 501(c)3.

- Saving Little Hearts

- Card-AG, The Cardiologycal Working Group of the University Pediatric Clinic Munster

- The Heart Chest

- American Heart Association

- Congenital Heart Defect

- Treating Congenital Heart Disease

- Coping with Congenital Heart Disease

- Fetal Treatment for Congenital Heart Disease (UCSF Fetal Treatment Center)

- EACTS Congenital Database ― European database of cardiothoracic surgeries with publicly available reports

- Adult Congenital Heart Association

- Congenital Heart Information Network

- Fixing Tiny Tickers - Fetal heart surgery

- Tiny Tickers - Antenatal congenital heart disease information

- Cardiacdiseases.org

Sources

- The ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities [1]

References

1. “The Heart Chest.” Non-profit Organization.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NAM III, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hammill SC, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Newby LK, Page RL, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices). Circulation. 2008; 117: 2820–2840. PMID 18483207

de:Herzfehler lv:Iedzimtās sirds slimības nn:Medfødd hjartefeil sr:Урођене срчане мане uk:Вроджені вади серця wa:Maladeye des bleus påpåds