Ascites pathophysiology

|

Ascites Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Ascites pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Ascites pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Ascites pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Eiman Ghaffarpasand, M.D. [2]

Overview

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis

- Ascites is excess accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity. The fluid can be defined as a transudate or an exudate. Amounts of up to 25 liters are fully possible.[1]

- Roughly, transudates are a result of increased pressure in the portal vein (>8 mmHg), such as cirrhosis; while exudates are actively secreted fluid due to inflammation or malignancy.

- Exudates:

- high in protein

- High in lactate dehydrogenase

- Low pH (< 7.30)

- Low glucose level

- High white blood cells count

- Transudates:

- Low protein (< 30 g/L)

- Low lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

- High pH

- Normal glucose

- Fewer than 1 white cell per 1000 mm³

Serum Albumin Ascites Gradiant (SAAG)

- The most useful measure is the difference between ascitic and serum albumin concentrations.

- A difference of less than 1.1 g/dl (10 g/L) implies an exudate.

Cirrhotic Ascites

- The main pathophysiology of ascites in cirrhotic patients consists of three interrelated mechanisms, include:[2]

- Portal hypertension

- Vasodilation

- Hyperaldosteronism

- There is a nitric oxide overload in cirrhotic patients from an unknown source. Therefore, they involved in hypovolemia secondary to the systemic vasodilation.[3]

- The visodialtion induced by nitric oxide would trigger the stimulation of juxta-glumerular system to upregulate antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and sympathetic drive.[4] Excess ADH causes water retention and volume overload.[5]

- Despite the normal physiology of vessels, angiotensin would not cause vasoconstriction in cirrhotic patients and vasodilation becomes perpetuated.[6]

- Portal hypertension leads to more production of lymph, to the extend of lymphatic system overload. Then, the lymphatic overflow will directed into to peritoneal cavity, forming ascites.[7]

Non-Cirrhotic Ascites

- Peritoneal malignancy produces some protein factors into the peritoneum, which may lead to osmotic drainage of water and fluid accumulation. Tuberculosis and other forms of ascites are induced through the same mechanism and osmotic fluid shift.[8]

- Pancreatic and biliary ascites are induced through leakage of pancreatic secretions or bile into the peritoneal cavity, which may lead to inflammatory fluid shift and accumulation.

| ↑Renin-angiotensin system | ↑Sympathetic nervous system | ↑Antidiuretic hormone | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systemic circulation | Renal circulation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arterial vasoconstriction | ↑Tubular Na and H2O reabsorbtion | Renal vasoconstriction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arterial hypertension | Na and H2O excretion | Hepatorenal syndrome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fluid overload | Dilutional hyponatremia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ascites formation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Genetics

- There is no genetic background for ascites.

- Ascites syndrome, also called pulmonary hypertension, is in fact a genetic disorder in broilers and poultry.[9]

Associated Conditions

Associated conditions with ascites are as following:[10]

- Cirrhosis

- Heart failure

- Portal hypertension

- Kwashiorkor

- Viral hepatitis

- Pancreatic disease

- Biliary disease

Gross Pathology

- On gross pathology, clear to pale yellow fluid accumulation in peritoneal space are characteristic findings of ascites under normal condition.[11]

Chylous ascites

- Chylous ascites gross pathology is milky presentation of ascites fluid, which is reflective of high amounts of chylomicrons.[12]

- On gross pathology, milky appearance of ascitic fluid is characteristics of the followings:[13]

- Cirrhosis

- Infections (parasitic and tuberculosis)

- Malignancy

- Congenital defects

- Traumatism

- Inflammatory processes

- Nephropathies

- Cardiopathies

Pseudochylous ascites

- Pseudochylous is the condition in which on gross pathology the ascitic fluid appearance is cloudy and/or turbid.

- The following conditions can lead to pseudochylous:[14]

- Bacterial infection

- Peritonitis, pancreatitis

- Perforated bowel

Bloody ascites

- On gross pathology, bloody appearance of ascitic fluid is characteristics of the followings:[15]

- Benign or malignant tumors

- Hemorrhagic pancreatitis

- Perforated ulcer

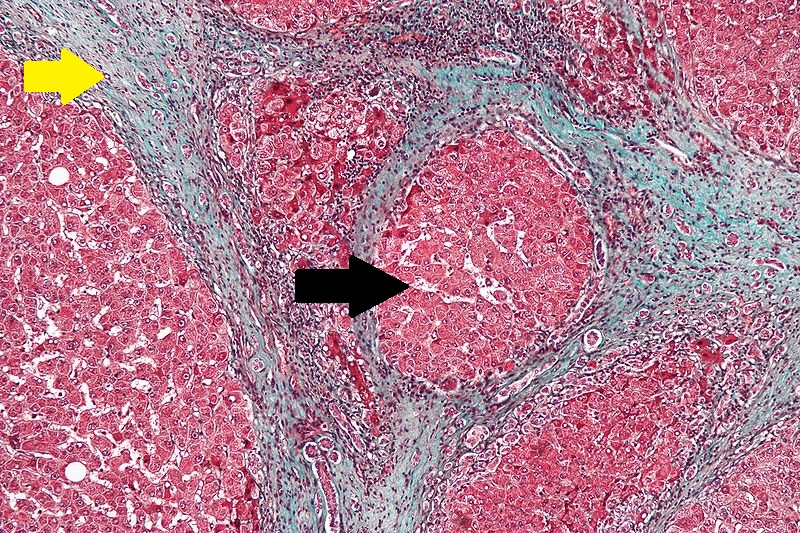

Microscopic Pathology

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, characteristic findings of cirrhosis, as the most common cause of ascites, are based on Robbins definition (all three is needed for diagnosis):[17]

References

- ↑ Runyon BA (2009). "Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: an update". Hepatology. 49 (6): 2087–107. doi:10.1002/hep.22853. PMID 19475696.

- ↑ Giefer, Matthew J; Murray, Karen F; Colletti, Richard B (2011). "Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Pediatric Ascites". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 52 (5): 503–513. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e318213f9f6. ISSN 0277-2116.

- ↑ La Villa, Giorgio; Gentilini, Paolo (2008). "Hemodynamic alterations in liver cirrhosis". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 29 (1–2): 112–118. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.010. ISSN 0098-2997.

- ↑ Leiva JG, Salgado JM, Estradas J, Torre A, Uribe M (2007). "Pathophysiology of ascites and dilutional hyponatremia: contemporary use of aquaretic agents". Ann Hepatol. 6 (4): 214–21. PMID 18007550.

- ↑ Bichet, Daniel (1982). "Role of Vasopressin in Abnormal Water Excretion in Cirrhotic Patients". Annals of Internal Medicine. 96 (4): 413. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-96-4-413. ISSN 0003-4819.

- ↑ Hennenberg, M.; Trebicka, J.; Kohistani, A. Z.; Heller, J.; Sauerbruch, T. (2009). "Vascular hyporesponsiveness to angiotensin II in rats with CCl4-induced liver cirrhosis". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 39 (10): 906–913. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02181.x. ISSN 0014-2972.

- ↑ Laine GA, Hall JT, Laine SH, Granger J (1979). "Transsinusoidal fluid dynamics in canine liver during venous hypertension". Circ. Res. 45 (3): 317–23. PMID 572270.

- ↑ Goodman GM, Gourley GR (1988). "Ascites complicating ventriculoperitoneal shunts". J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 7 (5): 780–2. PMID 3054040.

- ↑ Pakdel, A.; van Arendonk, J.A.M.; Vereijken, A.L.J.; Bovenhuis, H. (2010). "Genetic parameters of ascites-related traits in broilers: effect of cold and normal temperature conditions". British Poultry Science. 46 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1080/00071660400023938. ISSN 0007-1668.

- ↑ Moore KP, Aithal GP (2006). "Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis". Gut. 55 Suppl 6: vi1–12. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.099580. PMC 1860002. PMID 16966752.

- ↑ Huang LL, Xia HH, Zhu SL (2014). "Ascitic Fluid Analysis in the Differential Diagnosis of Ascites: Focus on Cirrhotic Ascites". J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2 (1): 58–64. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2013.00010. PMC 4521252. PMID 26357618.

- ↑ Fukunaga, Naoto; Shomura, Yu; Nasu, Michihiro; Okada, Yukikatsu (2011). "Chylous Ascites as a Rare Complication After Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Surgery". Southern Medical Journal. 104 (5): 365–367. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3182142b7d. ISSN 0038-4348.

- ↑ Tarn, A. C.; Lapworth, R. (2010). "Biochemical analysis of ascitic (peritoneal) fluid: what should we measure?". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 47 (5): 397–407. doi:10.1258/acb.2010.010048. ISSN 0004-5632.

- ↑ Runyon BA, Akriviadis EA, Keyser AJ (1991). "The opacity of portal hypertension-related ascites correlates with the fluid's triglyceride concentration". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 96 (1): 142–3. PMID 2069132.

- ↑ Runyon BA, Hoefs JC, Morgan TR (1988). "Ascitic fluid analysis in malignancy-related ascites". Hepatology. 8 (5): 1104–9. PMID 3417231.

- ↑ "File:Cirrhosis high mag.jpg - Libre Pathology".

- ↑ Mitchell, Richard (2012). Pocket companion to Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1416054542.