Sandbox:Cherry: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 265: | Line 265: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| colspan="1" rowspan="1" style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #DCDCDC;" align="center" |[[Diverticulitis|Acute diverticulitis]] | | colspan="1" rowspan="1" style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #DCDCDC;" align="center" |[[Diverticulitis|Acute diverticulitis]] | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" |LLQ | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" |[[Left lower quadrant abdominal pain resident survival guide|LLQ]] or [[Right lower quadrant abdominal pain resident survival guide|RLQ]] (in case of Meckel's diverticulitis) | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | + | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | + | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | ± | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | ± | ||

| Line 274: | Line 274: | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" |− | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" |− | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | + | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | + | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | Positive in perforated diverticulitis | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | Positive in [[Perforation|perforated]] diverticulitis | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | + | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | + | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | + | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="center" | + | ||

| Line 285: | Line 285: | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="left" | | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #F5F5F5;" align="left" | | ||

* History of [[constipation]] | * History of [[constipation]] | ||

* History of painless [[Lower gastrointestinal bleeding|lower GI bleed]] (in case of Meckel's diverticulitis) | |||

|- | |- | ||

| style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #DCDCDC;" align="center" |[[Inflammatory bowel disease]] | | style="padding: 5px 5px; background: #DCDCDC;" align="center" |[[Inflammatory bowel disease]] | ||

| Line 732: | Line 733: | ||

===Image and text to the right=== | ===Image and text to the right=== | ||

<figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline>[[File:Global distribution of leptospirosis.jpg|577x577px]]</figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline> Recent out break of leptospirosis is reported in Bronx, New York and found 3 cases in the months January and February, 2017. | <figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline>[[File:Global distribution of leptospirosis.jpg|577x577px]]</figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline> Recent out break of leptospirosis is reported in Bronx, New York and found 3 cases in the months January and February, 2017. | ||

===Gallery=== | ===Gallery=== | ||

Revision as of 16:25, 8 January 2018

Pathophysiology prev

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5szNmKtyBW4%7C350}} |

|

Cirrhosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case studies |

|

Sandbox:Cherry On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Sandbox:Cherry |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief:

Overview

| Disease | Symptoms | Other features | Diagnosis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | Rectal pain | Weightloss | Fever | Type of GI bleeding | Diarrhea | Constipation | Laboratory findings | Radio-Imaging findings | ||

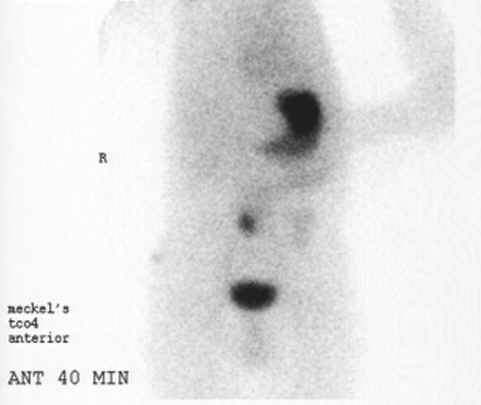

| Meckel's diverticulum | - | - | - | - | Frank blood | - | - |

|

Signs of iron deficiency anemia may be present such as:

|

|

| Diverticulosis | - | - | - | - | Red or maroon-colored blood | - | + |

|

Normal |

Globular outpouchings on CT scan |

| Angiodysplasia | - | - | - | - | Frank blood | - | - |

|

Normal | Normal |

| Hemorrhoids | - | + | - | - | Blood on tissues | - | + |

|

- | Tortuous dilated vessels on anoscopy |

| Anal fissures | - | + | - | - | Blood on tissues | - | + |

|

Normal except mild leucocytosis | Anoscopy |

| Mesenteric Ischemia | + | - | + | + | Frank blood | + | - |

|

| |

| Ischemic colitis | + | - | - | + | Frank blood | + | - | 3 phases

|

|

|

| Crohn's disease | + | - | + | + | Blood mixed with stools | + | + | Extra intestinal manifestations |

| |

| Ulcerative colitis | + | + | + | + | Blood mixed with stools | + | + |

|

|

|

| Colon carcinoma | + | -† | + | + | Occult bleeding | + | +† | + FOBT (fecal occult blood test)

↑ CEA( and CA 19-9 |

||

The following table differentiates all the diseases presenting with abdominal pain and lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Abbreviations: RUQ= Right upper quadrant of the abdomen, LUQ= Left upper quadrant, LLQ= Left lower quadrant, RLQ= Right lower quadrant, LFT= Liver function test, SIRS= Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, ERCP= Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, IV= Intravenous, N= Normal, AMA= Anti mitochondrial antibodies, LDH= Lactate dehydrogenase, GI= Gastrointestinal, CXR= Chest X ray, IgA= Immunoglobulin A, IgG= Immunoglobulin G, IgM= Immunoglobulin M, CT= Computed tomography, PMN= Polymorphonuclear cells, ESR= Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP= C-reactive protein, TS= Transferrin saturation, SF= Serum Ferritin, SMA= Superior mesenteric artery, SMV= Superior mesenteric vein, ECG= Electrocardiogram

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cirrhosis occurs due to long term liver injury which causes an imbalance between matrix production and degradation. Early disruption of the normal hepatic matrix results in its replacement by scar tissue, which in turn has deleterious effects on cell function.

Surgery

Incidentally discovered Meckel diverticulum

When a Meckel diverticulum is incidentally discovered at laparoscopy or laparotomy, the surgeon must decide whether to resect. Most surgeons generally do not resect a diverticulum with a wide mouth. However, a diverticulum with a narrow neck, which may obstruct or twist, can be easily resected at the neck without the need for segmental resection. A diverticulum deemed abnormal because of inflammation, thickening, or intramural pathology should be resected, with the decision for local or segmental resection based on the pathology. [5]

In 1976, Soltero and Bill reported that the lifetime risk of complications from Meckel diverticulum was 4.2% and that the risk decreased with age. [9] Their data indicated that 800 asymptomatic diverticula would have to be removed to save the life of one patient. On that basis, they opposed surgical excision.

Miltiadis et al stated that resection of incidentally found Meckel diverticulum protected patients from future surgery caused by complications of Meckel diverticulum. This strategy could help reduce morbidity and mortality, especially in elderly patients.

Cullen et al reported that prophylactic diverticulectomy is warranted to eliminate the possibility of future deaths. [3] As a result, they advocated diverticulectomy for asymptomatic disease even in the older age group.

Overall, selected cases of incidentally discovered diverticula in adults and most asymptomatic diverticula found in children [10] may be removed. Resection is recommended in the following cases:

Patients younger than 40 years Diverticula longer than 2 cm Diverticula with narrow necks Diverticula with fibrous bands Suspected ectopic gastric tissue Inflamed, thickened diverticula Removal of a healthy diverticulum in the presence of peritonitis, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, or any other complication that would militate against resection is not advised.

Meckel

References

the end

-

Portal HTN results from the combination of the following:

- Structural disturbances associated with advanced liver disease account for 70% of total hepatic vascular resistance.

- Functional abnormalities such as endothelial dysfunction and increased hepatic vascular tone account for 30% of total hepatic vascular resistance.

Pathogenesis of Cirrhosis due to Alcohol:

- More than 66 percent of all American adults consume alcohol.

- Cirrhosis due to alcohol accounts for approximately forty percent of mortality rates due to cirrhosis.

- Mechanisms of alcohol-induced damage include:

- Impaired protein synthesis, secretion, glycosylation

- Ethanol intake leads to elevated accumulation of intracellular triglycerides by:

- Lipoprotein secretion

- Decreased fatty acid oxidation

- Increased fatty acid uptake

- Alcohol is converted by Alcohol dehydrogenase to acetaldehyde.

- Due to the high reactivity of acetaldehyde, it forms acetaldehyde-protein adducts which cause damage to cells by:

- Trafficking of hepatic proteins

- Interrupting microtubule formation

- Interfering with enzyme activities

- Damage of hepatocytes leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species that activate Kupffer cells.[1]

- Kupffer cell activation leads to the production of profibrogenic cytokines that stimulates stellate cells.

- Stellate cell activation leads to the production of extracellular matrix and collagen.

- Portal triads develop connections with central veins due to connective tissue formation in pericentral and periportal zones, leading to the formation of regenerative nodules.

- Shrinkage of the liver occurs over years due to repeated insults that lead to:

- Loss of hepatocytes

- Increased production and deposition of collagen

Pathology

- There are four stages of Cirrhosis as it progresses:

- Chronic nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis - inflammation and necrosis of portal tracts with lymphocyte infiltration leading to the destruction of the bile ducts.

- Development of biliary stasis and fibrosis

- Periportal fibrosis progresses to bridging fibrosis

- Increased proliferation of smaller bile ductules leading to regenerative nodule formation.

Causes

| Drugs and Toxins | Infections | Autoimmune | Metabolic | Biliary obstruction(Secondary bilary cirrhosis) | Vascular | Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Hepatitis B | Primary Biliary Cirrhosis | Wilson's disease | Cystic fibrosis | Chronic RHF | Sarcoidosis |

| Methotrexate | Hepatitis C | Autoimmune hepatitis | Hemochromatosis | Biliary atresia | Budd-Chiari syndrome | Intestinal

bypass operations for obesity |

| Isoniazid | Schistosoma japonicum | Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis | Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | Bile duct strictures | Veno-occlusive disease | Cryptogenic: unknown |

| Methyldopa | Porphyria | Gallstones | ||||

| Glycogen storage diseases (such as Galactosaemia, Abetalipoproteinaemia) |

Cirrhosis

Pathophysiology [2][3][4][5][6][1]

- When an injured issue is replaced by a collagenous scar, it is termed as fibrosis.

- When fibrosis of the liver reaches an advanced stage where distortion of the hepatic vasculature also occurs, it is termed as cirrhosis of the liver.

- The cellular mechanisms responsible for cirrhosis are similar regardless of the type of initial insult and site of injury within the liver lobule.

- Viral hepatitis involves the periportal region, whereas involvement in alcoholic liver disease is largely pericentral.

- If the damage progresses, panlobular cirrhosis may result.

- Cirrhosis involves the following steps: [7]

- Inflammation

- Hepatic stellate cell activation

- Angiogenesis

- Fibrogenesis

- Kupffer cells are hepatic macrophages responsible for Hepatic Stellate cell activation during injury.

- The hepatic stellate cell (also known as the perisinusoidal cell or Ito cell) plays a key role in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis/cirrhosis.

- Hepatic stellate cells(HSC) are usually located in the subendothelial space of Disse and become activated to a myofibroblast-like phenotype in areas of liver injury.

- Collagen and non collagenous matrix proteins responsible for fibrosis are produced by the activated Hepatic Stellate Cells(HSC).

- Hepatocyte damage causes the release of lipid peroxidases from injured cell membranes leading to necrosis of parenchymal cells.

- Activated HSC produce numerous cytokines and their receptors, such as PDGF and TGF-f31 which are responsible for fibrogenesis.

- The matrix formed due to HSC activation is deposited in the space of Disse and leads to loss of fenestrations of endothelial cells, which is a process called capillarization.

- Cirrhosis leads to hepatic microvascular changes characterised by [8]

- formation of intra hepatic shunts (due to angiogenesis and loss of parenchymal cells)

- hepatic endothelial dysfunction

- The endothelial dysfunction is characterised by [9]

- insufficient release of vasodilators, such as nitric oxide due to oxidative stress

- increased production of vasoconstrictors (mainly adrenergic stimulation and activation of endothelins and RAAS)

- Fibrosis eventually leads to formation of septae that grossly distort the liver architecture which includes both the liver parenchyma and the vasculature. A cirrhotic liver compromises hepatic sinusoidal exchange by shunting arterial and portal blood directly into the central veins (hepatic outflow). Vascularized fibrous septa connect central veins with portal tracts leading to islands of hepatocytes surrounded by fibrous bands without central veins.[10][11][12]

- The formation of fibrotic bands is accompanied by regenerative nodule formation in the hepatic parenchyma.

- Advancement of cirrhosis may lead to parenchymal dysfunction and development of portal hypertension.

- Portal HTN results from the combination of the following:

- Structural disturbances associated with advanced liver disease account for 70% of total hepatic vascular resistance.

- Functional abnormalities such as endothelial dysfunction and increased hepatic vascular tone account for 30% of total hepatic vascular resistance.

Pathogenesis of Cirrhosis due to Alcohol:

- More than 66 percent of all American adults consume alcohol.

- Cirrhosis due to alcohol accounts for approximately forty percent of mortality rates due to cirrhosis.

- Mechanisms of alcohol-induced damage include:

- Impaired protein synthesis, secretion, glycosylation

- Ethanol intake leads to elevated accumulation of intracellular triglycerides by:

- Lipoprotein secretion

- Decreased fatty acid oxidation

- Increased fatty acid uptake

- Alcohol is converted by Alcohol dehydrogenase to acetaldehyde.

- Due to the high reactivity of acetaldehyde, it forms acetaldehyde-protein adducts which cause damage to cells by:

- Trafficking of hepatic proteins

- Interrupting microtubule formation

- Interfering with enzyme activities

- Damage of hepatocytes leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species that activate Kupffer cells.[1]

- Kupffer cell activation leads to the production of profibrogenic cytokines that stimulates stellate cells.

- Stellate cell activation leads to the production of extracellular matrix and collagen.

- Portal triads develop connections with central veins due to connective tissue formation in pericentral and periportal zones, leading to the formation of regenerative nodules.

- Shrinkage of the liver occurs over years due to repeated insults that lead to:

- Loss of hepatocytes

- Increased production and deposition of collagen

Pathology

- There are four stages of Cirrhosis as it progresses:

- Chronic nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis - inflammation and necrosis of portal tracts with lymphocyte infiltration leading to the destruction of the bile ducts.

- Development of biliary stasis and fibrosis

- Periportal fibrosis progresses to bridging fibrosis

- Increased proliferation of smaller bile ductules leading to regenerative nodule formation.

Video codes

Normal video

{{#ev:youtube|x6e9Pk6inYI}}

Video in table

Floating video

| Title |

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ypYI_lmLD7g%7C350}} |

Redirect

- REDIRECTEsophageal web

synonym website

https://mq.b2i.sg/snow-owl/#!terminology/snomed/10743008

Image

Image to the right

|

Image and text to the right

<figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline><figure-inline> </figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline> Recent out break of leptospirosis is reported in Bronx, New York and found 3 cases in the months January and February, 2017.

</figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline></figure-inline> Recent out break of leptospirosis is reported in Bronx, New York and found 3 cases in the months January and February, 2017.

Gallery

-

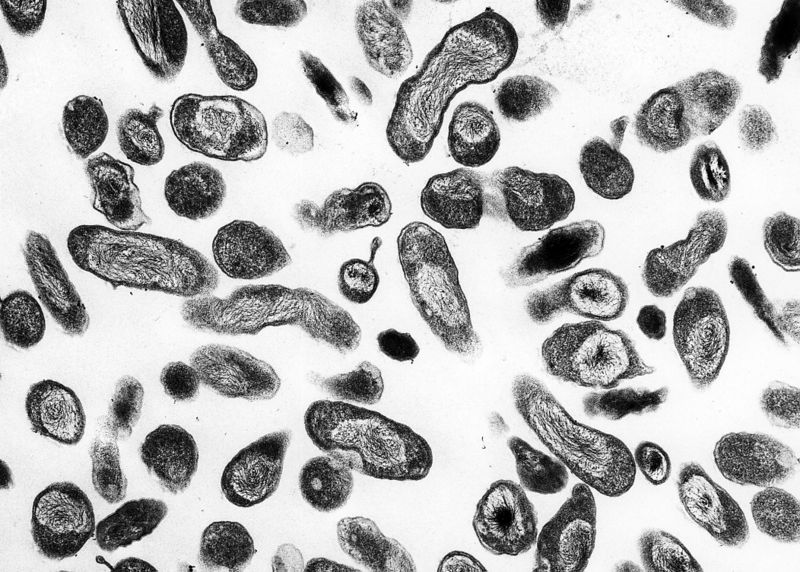

Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[13]

-

Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Chromogranin A immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[13]

-

Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Insulin immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[13]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Arthur MJ (2002). "Reversibility of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis following treatment for hepatitis C". Gastroenterology. 122 (5): 1525–8. PMID 11984538.

- ↑ Arthur MJ, Iredale JP (1994). "Hepatic lipocytes, TIMP-1 and liver fibrosis". J R Coll Physicians Lond. 28 (3): 200–8. PMID 7932316.

- ↑ Friedman SL (1993). "Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. The cellular basis of hepatic fibrosis. Mechanisms and treatment strategies". N. Engl. J. Med. 328 (25): 1828–35. doi:10.1056/NEJM199306243282508. PMID 8502273.

- ↑ Iredale JP (1996). "Matrix turnover in fibrogenesis". Hepatogastroenterology. 43 (7): 56–71. PMID 8682489.

- ↑ Gressner AM (1994). "Perisinusoidal lipocytes and fibrogenesis". Gut. 35 (10): 1331–3. PMC 1374996. PMID 7959178.

- ↑ Iredale JP (2007). "Models of liver fibrosis: exploring the dynamic nature of inflammation and repair in a solid organ". J. Clin. Invest. 117 (3): 539–48. doi:10.1172/JCI30542. PMC 1804370. PMID 17332881.

- ↑ Wanless IR, Wong F, Blendis LM, Greig P, Heathcote EJ, Levy G (1995). "Hepatic and portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: possible role in development of parenchymal extinction and portal hypertension". Hepatology. 21 (5): 1238–47. PMID 7737629.

- ↑ Fernández M, Semela D, Bruix J, Colle I, Pinzani M, Bosch J (2009). "Angiogenesis in liver disease". J. Hepatol. 50 (3): 604–20. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.011. PMID 19157625.

- ↑ García-Pagán JC, Gracia-Sancho J, Bosch J (2012). "Functional aspects on the pathophysiology of portal hypertension in cirrhosis". J. Hepatol. 57 (2): 458–61. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.007. PMID 22504334.

- ↑ Schuppan D, Afdhal NH (2008). "Liver cirrhosis". Lancet. 371 (9615): 838–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. PMC 2271178. PMID 18328931.

- ↑ Desmet VJ, Roskams T (2004). "Cirrhosis reversal: a duel between dogma and myth". J. Hepatol. 40 (5): 860–7. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2004.03.007. PMID 15094237.

- ↑ Wanless IR, Nakashima E, Sherman M (2000). "Regression of human cirrhosis. Morphologic features and the genesis of incomplete septal cirrhosis". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 124 (11): 1599–607. doi:10.1043/0003-9985(2000)124<1599:ROHC>2.0.CO;2. PMID 11079009.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas. Libre Pathology. http://librepathology.org/wiki/index.php/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas

REFERENCES

![Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[13]](/images/2/2f/Pancreatic_insulinoma_histology_2.JPG)

![Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Chromogranin A immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[13]](/images/a/a3/Pancreatic_insulinoma_histopathology_3.JPG)

![Histopathology of a pancreatic endocrine tumor (insulinoma). Insulin immunostain. Source:https://librepathology.org/wiki/Neuroendocrine_tumour_of_the_pancreas[13]](/images/d/d5/Pancreatic_insulinoma_histology_4.JPG)