Whipple's disease pathophysiology

|

Whipple's disease Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Whipple's disease pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Whipple's disease pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Whipple's disease pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Sadaf Sharfaei M.D.[2]

Overview

Whipple’s disease is a rare systemic disease. Therefore, some aspects of pathogenesis have remained unclear. Tropheryma whipplei is usually transmitted through oral route to human hosts. There is no known causative genetic factor for Whipple's disease. However, genetic and immunologic factors play important roles in clinical manifestation of Tropheryma whipplei infection. Individuals with positive HLA-B27 and defective cellular immunity including AIDS are at risk for Whipple's disease. Impaired macrophage function and cellular immunity are the main factors in replication of the bacteria and disease expansion to every tissue. There is a decreased activity of the T helper cells type 1 and increased activity of the T helper cells type 2. Defective phagocytic system is responsible for replication of bacteria in macrophages and spread of bacteria to other tissues. Characteristic of Whipple's disease is presence of foamy macrophages in the lamina propria that is periodic acid-Schiff stain positive.

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis

- Whipple's disease is a rare bacterial systemic infection caused by Tropheryma whipplei.[1]

- Tropheryma whipplei is a periodic acid-Schiff stain positive, gram-positive bacillus of Actinomycetes family.[2]

- The bacterium lives in soil and wastewater. Farmers and everyone who has any contact with contaminated soil and water are at high risk of the infection.[3]

- It is transmitted through oro-oral and feco-oral routes. The poor sanitation is associated with Tropheryma whipplei infection.[4]

- It is believed that human being is the only host for this bacterium.[5]

- Tropheryma whipplei invades intestines primarily and then every other organ including the heart, CNS, joints, lymph nodes, lungs, eyes, kidneys, bone marrow, and skin. Tissues are infected by macrophage infiltration contaminated by Tropheryma whipplei. Tropheryma whipplei multiplies in macrophages and monocytes.[6] Although there is a massive infiltration of the intestinal mucosa with the bacteria, the immunologic response is not adequate to limit the infection. Bacterium-infected macrophages express less CD11b which leads to inappropriate antigen presentation. These macrophages are unable to turn into mature phagosomes and lower the thioredoxin expression. The impairment in T-helper 1 cells differentiation leads to the inability of the immune system to kill the bacteria.[7][8]

- Tropheryma whipplei infection causes four different clinical manifestations: acute infection, asymptomatic carrier state, the classic Whipple’s disease, and localized chronic infection.[9][10]

| Contamination via oro-oral or feco-oral route | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Acute infection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antibody production | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strong immune response | Insufficient immune response | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Complete eradication | Chronic carrier | Chronic infection | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Classic Whipple's disease | Localized infection | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cure | Relapse | Re-infection | Death | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Immunologic response

- It is believed that host immunologic response to Tropheryma whipplei plays an important role on the clinical manifestation of the disease.[6]

- Several studies suggested that the defective cellular immunity and humoral immunity may lead to the proliferation of the bacteria and clinical manifestation of the Whipple's disease.[8]

Followings are some of the observations that indicate the immunologic nature of the Whipple's disease:

Defective cellular immunity

- Reduced T cell proliferative response[8]

- Decreased CD4/CD8 ratio[11]

- Decreased T helper cells type 1 response and subsequently reduced production of interleukin 2 (IL-2)

- Enhanced expression of interleukin 4 (IL-4) and functional activity of T helper cells type 2 (Th2)[12]

- Increased numbers of regulatory T cells[13]

- Reduced peripheral T cell proliferation to phytohemagglutinin and concanavalin A[8]

- Up-regulated Interleukin 16 (IL-16) in monocyte-derived macrophages that enhanced Tropheryma whipplei replication[14]

Defective macrophagic/phagocytic system

- Reduced Interleukin 12 (IL-12) production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells that leads to decreased functional activity of T helper cells type 1 (Th1) and subsequently decreased Interferon gamma secretion by peripheral blood mononuclear cells[15][16][12]

- Reduced expression of complement receptor 3 (CD11b)[8]

- Normal phagocytosis but impaired degradation[15]

Defective humoral immunity

- Increased Immunoglobulin M production in the lamina propria[11]

- Reduced Serum Immunoglobulin G2, an Interferon gamma dependent immunoglobulin subclass, and serum TGF-beta levels[15]

Genetics

There is no known causative genetic factor for Whipple's disease. However, there is an association between Whipple's disease and some immunologic defects.

- Studies showed that individuals with specific HLA type (HLA alleles DRB1*13 and DQB1*06) have a higher risk of Whipple's disease.[9]

Associated Conditions

The most important conditions associated with Whipple's disease include:

- HLA-B27 individuals

- Defective cellular immunity

- HIV infection

Gross Pathology

- On endoscopy, pale yellow mucosa with whitish spots, greenish brown and erythematous patches, and both engorged and flattened folds are characteristic findings of Whipple's disease.[17]

Microscopic Pathology

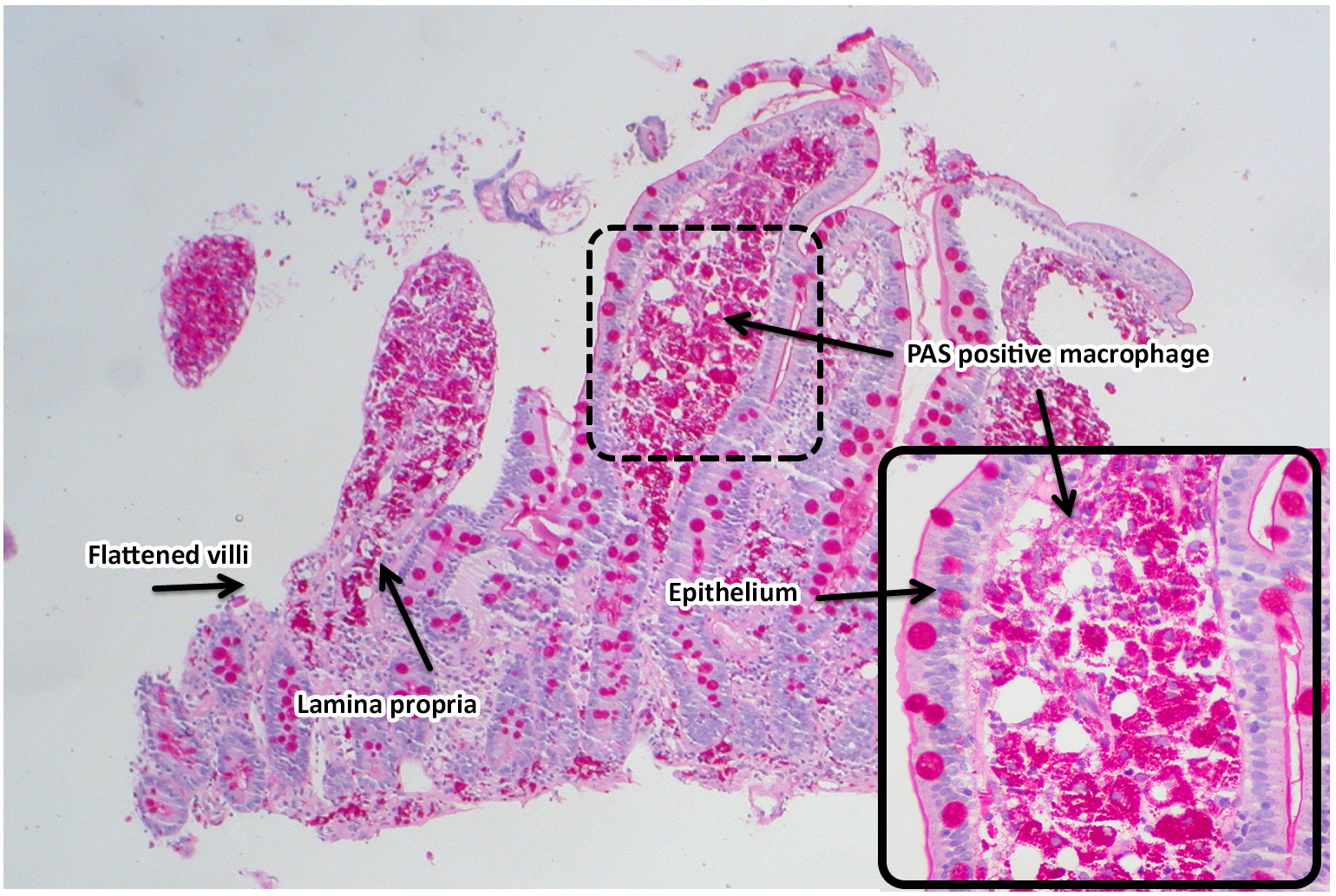

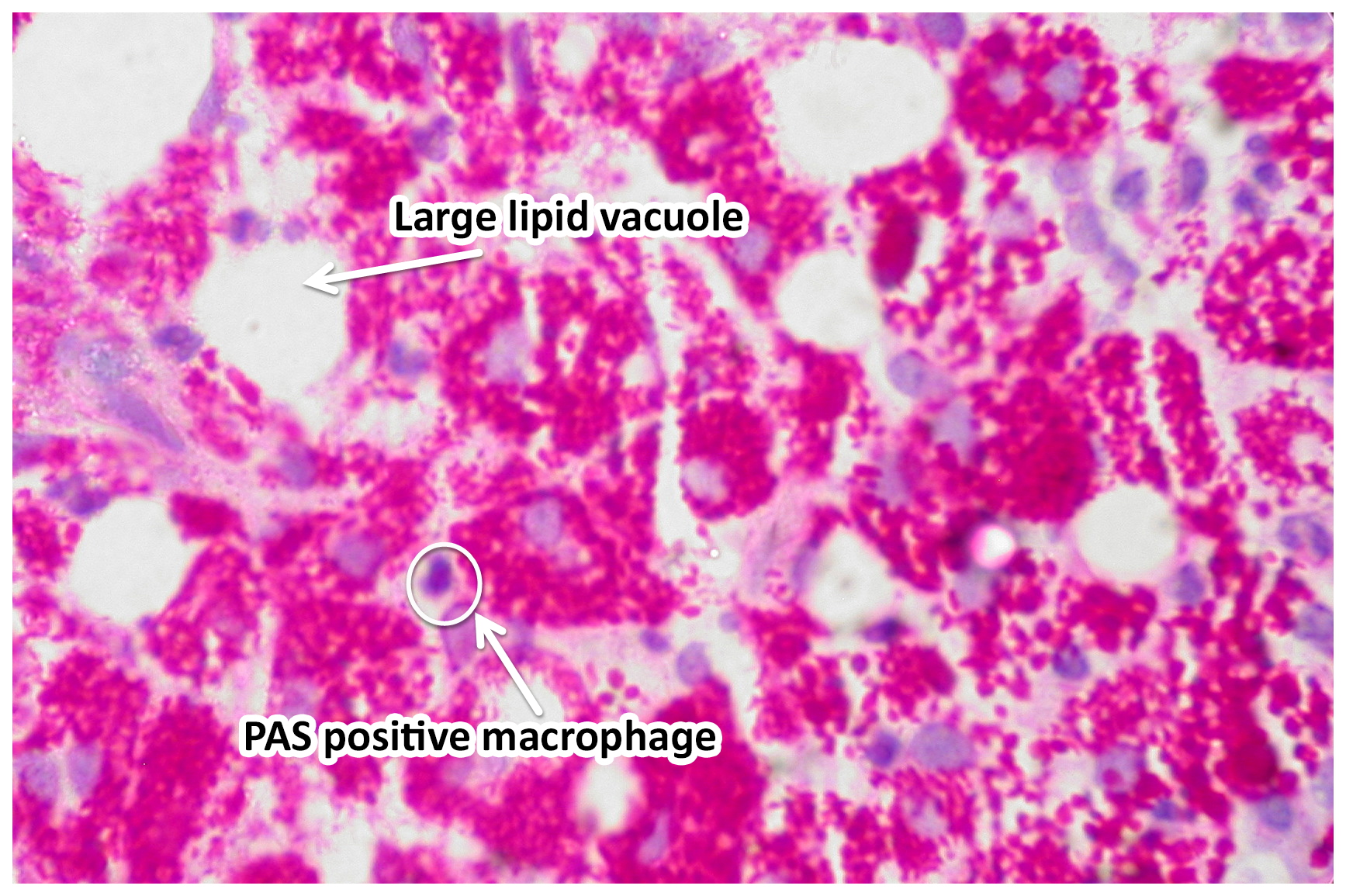

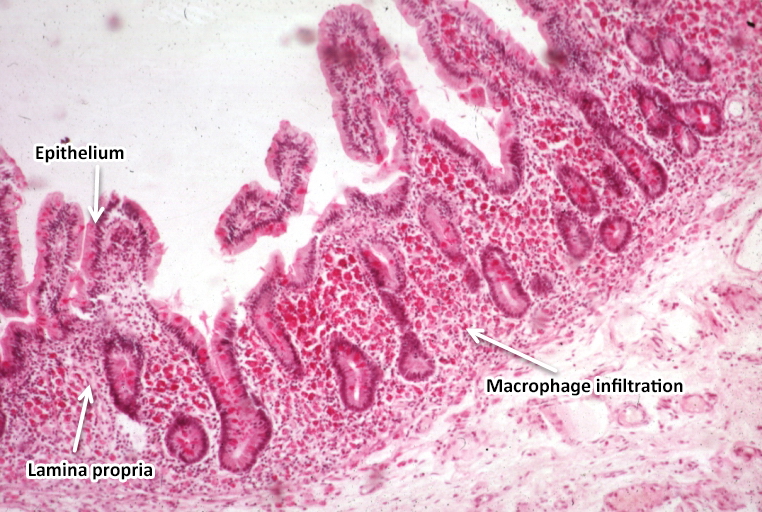

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, PAS-positive macrophages in the lamina propria containing non-acid-fast gram-positive bacilli are characteristic findings of Whipple's disease.[17][18]

Below images show the characteristic feature of Whipple's disease: foamy macrophages are present in the lamina propria.[19]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- ↑ Schneider T, Moos V, Loddenkemper C, Marth T, Fenollar F, Raoult D (2008). "Whipple's disease: new aspects of pathogenesis and treatment". Lancet Infect Dis. 8 (3): 179–90. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70042-2. PMID 18291339.

- ↑ Schwartzman, Sergio; Schwartzman, Monica (2013). "Whipple's Disease". Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 39 (2): 313–321. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2013.03.005. ISSN 0889-857X.

- ↑ Keita, Alpha Kabinet; Diatta, Georges; Ratmanov, Pavel; Bassene, Hubert; Raoult, Didier; Roucher, Clémentine; Fenollar, Florence; Sokhna, Cheikh; Tall, Adama; Trape, Jean-François; Mediannikov, Oleg (2013). "Looking for Tropheryma whipplei Source and Reservoir in Rural Senegal". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 88 (2): 339–343. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0614. ISSN 0002-9637.

- ↑ Keita, Alpha Kabinet; Brouqui, Philippe; Badiaga, Sékéné; Benkouiten, Samir; Ratmanov, Pavel; Raoult, Didier; Fenollar, Florence (2013). "Tropheryma whipplei prevalence strongly suggests human transmission in homeless shelters". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 17 (1): e67–e68. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2012.05.1033. ISSN 1201-9712.

- ↑ Marth, Thomas; Moos, Verena; Müller, Christian; Biagi, Federico; Schneider, Thomas (2016). "Tropheryma whipplei infection and Whipple's disease". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (3): e13–e22. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00537-X. ISSN 1473-3099.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Marth T, Strober W (1996). "Whipple's disease". Semin. Gastrointest. Dis. 7 (1): 41–8. PMID 8903578.

- ↑ Dolmans, Ruben A. V.; Boel, C. H. Edwin; Lacle, Miangela M.; Kusters, Johannes G. (2017). "Clinical Manifestations, Treatment, and Diagnosis of Tropheryma whipplei Infections". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 30 (2): 529–555. doi:10.1128/CMR.00033-16. ISSN 0893-8512.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Marth T, Roux M, von Herbay A, Meuer SC, Feurle GE (1994). "Persistent reduction of complement receptor 3 alpha-chain expressing mononuclear blood cells and transient inhibitory serum factors in Whipple's disease". Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 72 (2): 217–26. PMID 7519533.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Marth, Thomas (2009). "New Insights into Whipple's Disease – A Rare Intestinal Inflammatory Disorder". Digestive Diseases. 27 (4): 494–501. doi:10.1159/000233288. ISSN 1421-9875.

- ↑ Street, Sara; Donoghue, Helen D; Neild, GH (1999). "Tropheryma whippelii DNA in saliva of healthy people". The Lancet. 354 (9185): 1178–1179. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03065-2. ISSN 0140-6736.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ectors N, Geboes K, De Vos R, Heidbuchel H, Rutgeerts P, Desmet V, Vantrappen G (1992). "Whipple's disease: a histological, immunocytochemical and electronmicroscopic study of the immune response in the small intestinal mucosa". Histopathology. 21 (1): 1–12. PMID 1378814.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Marth T, Kleen N, Stallmach A, Ring S, Aziz S, Schmidt C, Strober W, Zeitz M, Schneider T (2002). "Dysregulated peripheral and mucosal Th1/Th2 response in Whipple's disease". Gastroenterology. 123 (5): 1468–77. PMID 12404221.

- ↑ Schinnerling K, Moos V, Geelhaar A, Allers K, Loddenkemper C, Friebel J, Conrad K, Kühl AA, Erben U, Schneider T (2011). "Regulatory T cells in patients with Whipple's disease". J. Immunol. 187 (8): 4061–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101349. PMID 21918190.

- ↑ Desnues B, Raoult D, Mege JL (2005). "IL-16 is critical for Tropheryma whipplei replication in Whipple's disease". J. Immunol. 175 (7): 4575–82. PMID 16177102.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Marth T, Neurath M, Cuccherini BA, Strober W (1997). "Defects of monocyte interleukin 12 production and humoral immunity in Whipple's disease". Gastroenterology. 113 (2): 442–8. PMID 9247462.

- ↑ Schneider T, Stallmach A, von Herbay A, Marth T, Strober W, Zeitz M (1998). "Treatment of refractory Whipple disease with interferon-gamma". Ann. Intern. Med. 129 (11): 875–7. PMID 9867729.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Salkic, Nermin N.; Alibegovic, Ervin; Jovanovic, Predrag (2013). "Endoscopic appearance of duodenal mucosa in Whipple's disease". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 77 (5): 822–823. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.016. ISSN 0016-5107.

- ↑ Schneider, Thomas; Moos, Verena; Loddenkemper, Christoph; Marth, Thomas; Fenollar, Florence; Raoult, Didier (2008). "Whipple's disease: new aspects of pathogenesis and treatment". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 8 (3): 179–190. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70042-2. ISSN 1473-3099.

- ↑ https://commons.wikimedia.org

- ↑ "File:Whipples Disease, PAS (6881958655).jpg - Wikimedia Commons".

- ↑ "File:Whipples Disease, GMS (6881505399).jpg - Wikimedia Commons".

- ↑ "File:Whipple disease -a- high mag.jpg - Wikimedia Commons".

- ↑ "File:Whipples Disease, PAS (6881958605).jpg - Wikimedia Commons".

- ↑ "File:Whipple disease.jpg - Wikimedia Commons".

- ↑ "File:Whipple2.jpg - Wikimedia Commons". External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "File:Whipple pas+.jpg - Wikimedia Commons".

- ↑ "File:Whipples Disease, Kinyoun Carbolfuchsin Acid-Fast Stain (6881505345).jpg - Wikimedia Commons".