Pap smear

For patient information, click here

|

WikiDoc Resources for Pap smear |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Pap smear |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Pap smear at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Pap smear at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Pap smear

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Pap smear Discussion groups on Pap smear Directions to Hospitals Treating Pap smear Risk calculators and risk factors for Pap smear

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Pap smear |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [2]

Synonyms and keywords: Papanikolaou test; papanicolaou test; pap test; cervical smear; smear test

Overview

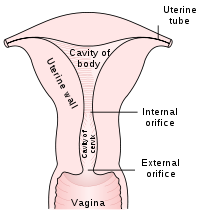

In gynecology, Pap smear is a medical screening method, invented by Georgios Papanikolaou, primarily designed to detect premalignant and malignant processes in the ectocervix. It may also detect infections and abnormalities in the endocervix and endometrium.

Procedure

The endocervix may be partially sampled with the device used to obtain the ectocervical sample, but due to the anatomy of this area, consistent and reliable sampling cannot be guaranteed. As abnormal endocervical cells may be sampled, those examining them are taught to recognize them.

The endometrium is not directly sampled with the device used to sample the ectocervix. Cells may exfoliate onto the cervix and be collected from there, so as with endocervical cells, abnormal cells can be recognised if present but the Pap Test should not be used as a screening tool for endometrial malignancy.

The pre-cancerous changes (called dysplasias or cervical or endocervical intraepithelial neoplasia) are usually caused by sexually transmitted human papillomaviruses (HPVs). The test aims to detect and prevent the progression of HPV-induced cervical cancer and other abnormalities in the female genital tract by sampling cells from the outer opening of the cervix (Latin for "neck") of the uterus and the endocervix. The sampling technique changed very little since its invention by Georgios Papanikolaou (1883–1962) to detect cyclic hormonal changes in vaginal cells in the early 20th century until the development of liquid based cell thinlayer technology. The test remains an effective, widely used method for early detection of cervical cancer and pre-cancer. The UK's call and recall system is among the best; estimates of its effectiveness vary widely but it may prevent about 700 deaths per year in the UK. It is not a perfect test. "A nurse performing 200 tests each year would prevent a death once in 38 years. During this time she or he would care for over 152 women with abnormal results, over 79 women would be referred for investigation, over 53 would have abnormal biopsy results, and over 17 would have persisting abnormalities for more than two years. At least one woman during the 38 years would die from cervical cancer despite being screened."[1] HPV vaccine may offer better prospects in the long term.

It is generally recommended that sexually active females seek Pap smear testing annually, although guidelines may vary from country to country. If results are abnormal, and depending on the nature of the abnormality, the test may need to be repeated in three to twelve months. If the abnormality requires closer scrutiny, the patient may be referred for detailed inspection of the cervix by colposcopy. The patient may also be referred for HPV DNA testing, which can serve as an adjunct (or even as an alternative) to Pap testing.

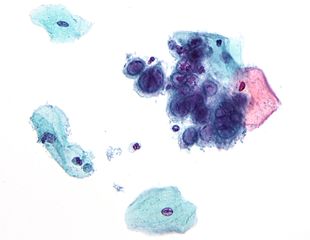

About 5% to 7% of pap smears produce abnormal results, such as dysplasia, possibly indicating a pre-cancerous condition. Although many low grade cervical dysplasias spontaneously regress without ever leading to cervical cancer, dysplasia can serve as an indication that increased vigilance is needed. Endocervical and endometrial abnormalities can also be detected, as can a number of infectious processes, including yeast and Trichomonas vaginalis. A small proportion of abnormalities are reported as of "uncertain significance".

Technical Aspects

Samples are collected from the outer opening or os of the cervix using an Aylesbury spatula or (more frequently with the advent of liquid-based cytology) a plastic-fronded broom. The cells are placed on a glass slide and checked for abnormalities in the laboratory.

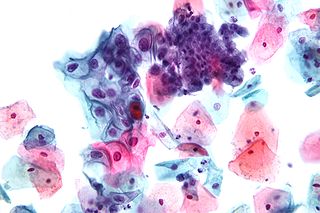

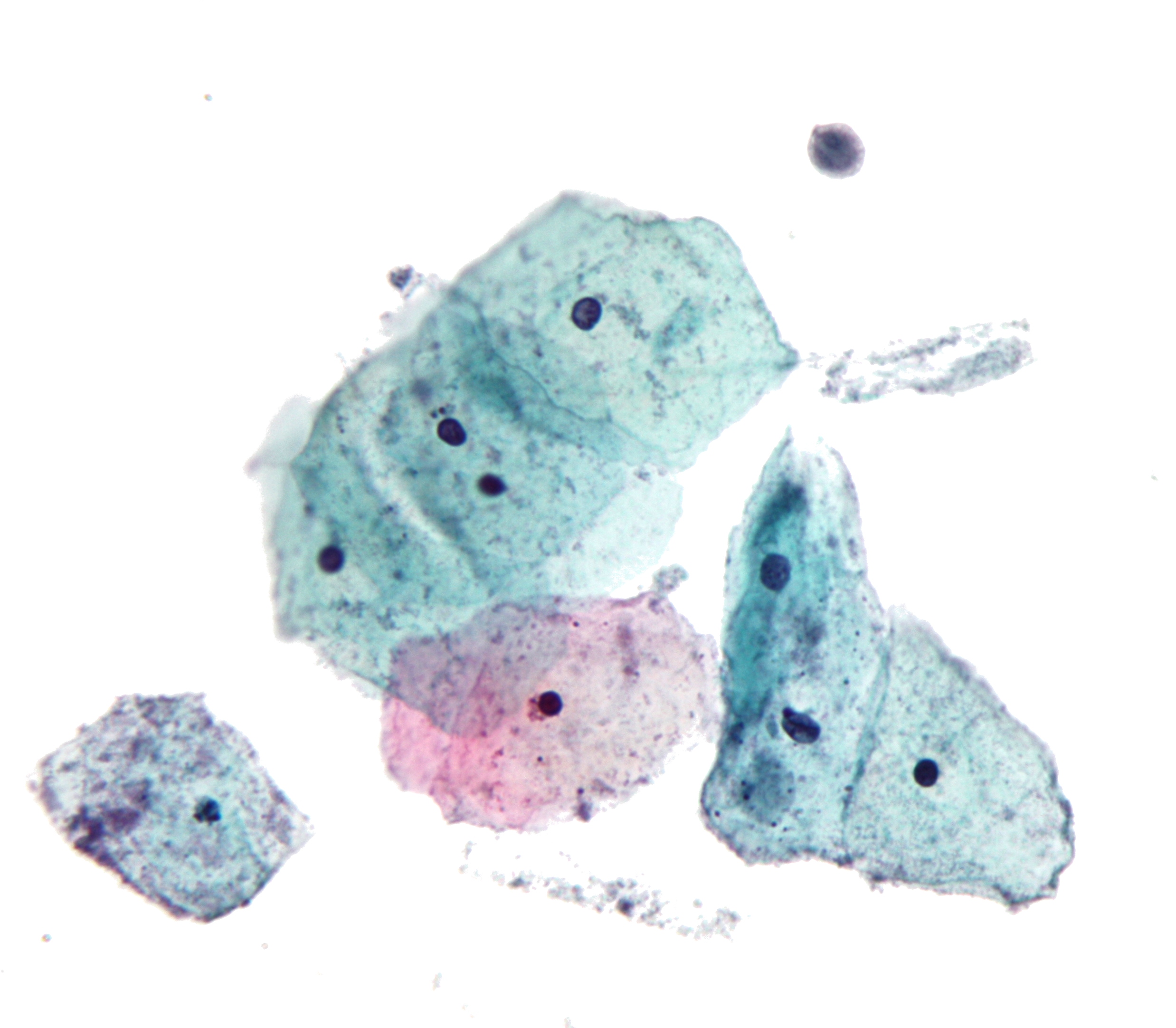

The sample is stained using the Papanicolaou technique, in which tinctorial dyes and acids are selectively retained by cells. Unstained cells can not be visualized with light microscopy. The stains chosen by Papanicolau were selected to highlight cytoplasmic keratinization, which actually has almost nothing to do with the nuclear features used to make diagnoses now.

The sample is then screened by a specially trained and qualified cytotechnologist using a light microscope. The terminology for who screens the sample varies according the country; in the UK, the personnel are known as Cytoscreeners, Biomedical scientists (BMS), Advanced Practitioners and Pathologists. The latter two take responsibility for reporting the abnormal sample which may require further investigation.

Studies of the accuracy of conventional cytology report:

- Sensitivity 72%[2]

- Specificity 94%[2]

In the United States, physicians who fail to diagnose cervical cancer from a pap smear have been convicted of negligent homicide. In 1988 and 1989, Karen Smith had received pap smears which were argued to have "unequivocally" shown that she had cancer; yet the lab had not made the diagnosis. She died on March 8 1995. Later, a physician and a laboratory technician were convicted of negligent homicide. These events have led to even more rigorous quality assurance programs, and to emphasizing that this is a screening, not a diagnostic, test, associated with a small irreducible error rate.

Liquid Based Monolayer Cytology

Since the mid-1990s, techniques based around placing the sample into a vial containing a liquid medium which preserves the cells have been increasingly used. The media are primarily ethanol based. Two of the types are Sure-Path (TriPath Imaging) and Thin-Prep (Cytyc Corp). Once placed into the vial, the sample is processed at the laboratory into a cell thin-layer, stained, and examined by light microscopy. The liquid sample has the advantage of being suitable for low and high risk HPV testing and reduced unsatisfactory specimens from 4.1% to 2.6%.[3] Proper sample acquisition is crucial to the accuracy of the test; clearly, a cell that is not in the sample cannot be evaluated.

Studies of the accuracy of liquid based monolayer cytology report:

- Sensitivity 61%[4] to 66%[2]

- Specificity 82%[4] to 91%[2]

Some[3], but not all studies[2][4], report increased sensitivity from the liquid based smears.

Results

In screening a general or low-risk population, most Pap results are normal.

In the United States, about 2–3 million abnormal Pap smear results are found each year.[5] Most abnormal results are mildly abnormal (ASC-US (typically 2–5% of Pap results) or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) (about 2% of results)), indicating HPV infection.[citation needed] Although most low-grade cervical dysplasias spontaneously regress without ever leading to cervical cancer, dysplasia can serve as an indication that increased vigilance is needed.

In a typical scenario, about 0.5% of Pap results are high-grade SIL (HSIL), and less than 0.5% of results indicate cancer; 0.2 to 0.8% of results indicate Atypical Glandular Cells of Undetermined Significance (AGC-NOS).[citation needed]

As liquid based preparations (LBPs) become a common medium for testing, atypical result rates have increased. The median rate for all preparations with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions using LBPs was 2.9% compared with a 2003 median rate of 2.1%. Rates for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (median, 0.5%) and atypical squamous cells have changed little.[6]

Abnormal results are reported according to the Bethesda system.[7] They include:

- Squamous cell abnormalities (SIL)

- Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

- Atypical squamous cells – cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H)

- Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LGSIL or LSIL)

- High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL or HSIL)

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Glandular epithelial cell abnormalities

- Atypical Glandular Cells not otherwise specified (AGC or AGC-NOS)

Endocervical and endometrial abnormalities can also be detected, as can a number of infectious processes, including yeast, herpes simplex virus and trichomoniasis. However it is not very sensitive at detecting these infections, so absence of detection on a Pap does not mean absence of the infection.

Effectiveness

The Pap test, when combined with a regular program of screening and appropriate follow-up, can reduce cervical cancer deaths by up to 80%.[8] Failure of prevention of cancer by the Pap test can occur for many reasons, including not getting regular screening, lack of appropriate follow up of abnormal results, and sampling and interpretation errors.[9] In the US, over half of all invasive cancers occur in women that have never had a Pap smear; an additional 10 to 20% of cancers occur in women that have not had a Pap smear in the preceding five years. About one-quarter of US cervical cancers were in women that had an abnormal Pap smear, but did not get appropriate follow-up (woman did not return for care, or clinician did not perform recommended tests or treatment).

Adenocarcinoma of the cervix has not been shown to be prevented by Pap tests.[9] In the UK, which has a Pap smear screening program, Adenocarcinoma accounts for about 15% of all cervical cancers[10]

Estimates of the effectiveness of the United Kingdom's call and recall system vary widely, but it may prevent about 700 deaths per year in the UK. A medical practitioner performing 200 tests each year would prevent a death once in 38 years, while seeing 152 women with abnormal results, referring 79 for investigation, obtaining 53 abnormal biopsy results, and seeing 17 persisting abnormalities lasting longer than two years. At least one woman during the 38 years would die from cervical cancer despite being screened.[1]

Since the population of the UK is about 61 million, the maximum number of women who could be receiving Pap smears in the UK is around 15 million to 20 million (eliminating the percentage of the population under 20 and over 65). This would indicate that the use of Pap smear screening in the UK saves the life of 1 person for every approximately 20,000 people tested (assuming 15,000,000 are being tested yearly). If only 10,000,000 are actually tested each year, then it would save the life of 1 person for every approximately 15,000 people tested.

Human Papillomavirus Testing

The presence of HPV indicates that the person has been infected, the majority of women who get infected will successfully clear the infection within 18 months. It is those who have an infection of prolonged duration with high risk types[11] (e.g. types 16,18,31,45) that are more likely to develop Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia due to the effects that HPV has on DNA.

Studies of the accuracy of HPV testing report:

- Sensitivity 88% to 91% (for detecting CIN 3 or higher)[4] to 97% (for detecting CIN2+)[12]

- Specificity 73% to 79% (for detecting CIN 3 or higher)[4] to 93% (for detecting CIN 3 or higher)[12]

By adding the more sensitive HPV Test, the specificity may decline. However, the drop in specificity is not definite. [13] If the specificity does decline, this results in increased numbers of false positive tests and many women who did not have disease having colposcopy[14] and treatment. A worthwhile screening test requires a balance between the sensitivity and specificity to ensure that those having a disease are correctly identified as having it and equally importantly those not identifying those without the disease as having it. Due to the liquid based pap smears having a false negative rate of 15-35%, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology[15] have recommended the use of HPV testing in addition to the pap smear in all women over the age of 30.

Regarding the role of HPV testing, randomized controlled trials have compared HPV to colposcopy. HPV testing appears as sensitive as immediate colposcopy while reducing the number of colposcopies needed.[16] Randomized controlled trial have suggested that HPV testing could follow abnormal cytology[4] or could precede cervical cytology examination.[12]

A study published in April 2007 suggested the act of performing a Pap smear produces an inflammatory cytokine response, which may initiate immunologic clearance of HPV, therefore reducing the risk of cervical cancer. Women who had even a single Pap smear in their history had a lower incidence of cancer. "A statistically significant decline in the HPV positivity rate correlated with the lifetime number of Pap smears received."[17]

Automated Analysis

In the last decade there have been successful attempts to develop automated, computer image analysis systems for screening.[18] Automation may improve sensitivity and reduce unsatisfactory specimens.[19] One of these has been FDA approved and functions in high volume reference laboratories, with human oversight.

Practical Aspects

The physician or operator collecting a sample for the test inserts a speculum into the patient's vagina, to obtain a cell sample from the cervix. A pap smear appointment is normally not scheduled during menstruation. The procedure is usually just slightly painful, because of the neuroanatomy of the cervix. However, this can depend on the patient's anatomy, the skill of the practitioner, psychological factors, and other conditions. Results usually take about 3 weeks. Slight bleeding, cramps, and other discomfort can occur afterwards.

Other tests, including the TruTest, an endometrial biopsy used for early detection of uterine cancer, can be performed during the same visit.

2012 ACS, ASCCP and ASCP Release New Screening Guidelines for Cervical Cancer (DO NOT EDIT)[20]

| “ |

|

” |

2012 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement for Screening for Cervical Cancer (DO NOT EDIT)[21]

| “ |

|

” |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Raffle AE, Alden B, Quinn M, Babb PJ, Brett MT (2003). "Outcomes of screening to prevent cancer: analysis of cumulative incidence of cervical abnormality and modelling of cases and deaths prevented". BMJ. 326 (7395): 901. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7395.901. PMID 12714468.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Coste J, Cochand-Priollet B, de Cremoux P; et al. (2003). "Cross sectional study of conventional cervical smear, monolayer cytology, and human papillomavirus DNA testing for cervical cancer screening". BMJ. 326 (7392): 733. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7392.733. PMID 12676841. ACP Journal Club

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ronco G, Cuzick J, Pierotti P; et al. (2007). "Accuracy of liquid based versus conventional cytology: overall results of new technologies for cervical cancer screening randomised controlled trial". doi:10.1136/bmj.39196.740995.BE. PMID 17517761.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Kulasingam SL, Hughes JP, Kiviat NB; et al. (2002). "Evaluation of human papillomavirus testing in primary screening for cervical abnormalities: comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and frequency of referral". JAMA. 288 (14): 1749–57. PMID 12365959.

- ↑ "Pap Smear". Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ↑ Eversole, GM; Moriarty, AT; Schwartz, MR; Clayton, AC; Souers, R; Fatheree, LA; Chmara, BA; Tench, WD; Henry, MR (2010). "Practices of participants in the college of american pathologists interlaboratory comparison program in cervicovaginal cytology, 2006". Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 134 (3): 331–5. doi:10.1043/1543-2165-134.3.331. PMID 20196659.

- ↑ Nayar R, Solomon D. Second edition of 'The Bethesda System for reporting cervical cytology' – Atlas, website, and Bethesda interobserver reproducibility project. CytoJournal [serial online] 2004 [cited 2011 Apr 16];1:4. Available from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2004/1/1/4/41272

- ↑ M. Arbyn; et al. (2010). "European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening. Second Edition—Summary Document". Annals of Oncology. 21 (3): 448–458. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp471. PMC 2826099. PMID 20176693.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 DeMay, M. (2007). Practical principles of cytopathology. Revised edition. Chicago, IL: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press. ISBN 978-0-89189-549-7.

- ↑ "Cancer Research UK website". Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ Cuschieri KS, Cubie HA, Whitley MW; et al. (2005). "Persistent high risk HPV infection associated with development of cervical neoplasia in a prospective population study". J. Clin. Pathol. 58 (9): 946–50. doi:10.1136/jcp.2004.022863. PMID 16126875.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Cuzick J, Szarewski A, Cubie H; et al. (2003). "Management of women who test positive for high-risk types of human papillomavirus: the HART study". Lancet. 362 (9399): 1871–6. PMID 14667741.

- ↑ Arbyn M, Buntinx F, Van Ranst M, Paraskevaidis E, Martin-Hirsch P, Dillner J (2004). "Virologic versus cytologic triage of women with equivocal Pap smears: a meta-analysis of the accuracy to detect high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 96 (4): 280–93. PMID 14970277.

- ↑ http://screening.iarc.fr/colpochap.php?lang=1&chap=4

- ↑ Wright TC, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB, Wilkinson EJ (2002). "2001 Consensus Guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities". JAMA. 287 (16): 2120–9. PMID 11966387.

- ↑ ASCUS-LSIL Traige Study (ALTS) Group. (2003). "Results of a randomized trial on the management of cytology interpretations of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 188 (6): 1383–92. PMID 12824967.

- ↑ [1], J Inflamm 2007;4.

- ↑ Biscotti CV, Dawson AE, Dziura B; et al. (2005). "Assisted primary screening using the automated ThinPrep Imaging System". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 123 (2): 281–7. PMID 15842055.

- ↑ Davey E, d'Assuncao J, Irwig L; et al. (2007). "Accuracy of reading liquid based cytology slides using the ThinPrep Imager compared with conventional cytology: prospective study". doi:10.1136/bmj.39219.645475.55. PMID 17604301.

- ↑ Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW; et al. (2012). "American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer". CA Cancer J Clin. 62 (3): 147–72. doi:10.3322/caac.21139. PMID 22422631.

- ↑ Moyer VA (2012). "Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Ann. Intern. Med. 156 (12): 880–91, W312. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424. PMID 22711081. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)