Tension pneumothorax resident survival guide

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mohamed Moubarak, M.D. [2]

Synonyms and keywords: Collapsed lung; air around the lung; air outside the lung

| Tension Pneumothorax Resident Survival Guide Microchapters |

|---|

| Overview |

| Causes |

| Diagnosis |

| Treatment |

| Do's |

| Don'ts |

Overview

Tension pneumothorax is a medical emergency caused by accumulation of air in the pleural cavity. Air enter the intrapleural space through the lung parenchyma, or through a traumatic communication from the chest wall. It tends to occur in clinical situations such as ventilation, resuscitation, trauma, or in patients with lung disease.[1] The aim of tension pneumothorax management is to relieve the pressure from thorax.

Causes

Life Threatening Causes

Tension pneumothorax is a life-threatening condition and must be treated as such irrespective of the underlying cause.

Common Causes

Tension pneumothorax can be a complication of primary, or secondary pneumothorax. The most common causes of tension pneumothorax are:

- Mechanical ventilation

- Trauma

- Central venous catheter

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- Emphysema

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Asthma

Diagnosis

Shown below is an algorithm depicting the diagnostic approach of tension pneumothorax based on the British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010.[1]

Characterize the symptoms:[1] Tension pneumothorax requires immediate intervention. Diagnosis should be made based on the history and physical examination findings. ❑ Breathlessness | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Consider risk factors: ❑ Recent invasive procedures ❑ Cigarette smoking

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Examine the patient: Vital signs ❑ Pulse:

Focused chest examination:[1] Inspection ❑ Reduced lung expansion on the affected side Palpation ❑ Trachea shifted to the opposite side Percussion Auscultation ❑ Diminished breath sounds on the affected side | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Consider alternative diagnoses:

❑ Asthma

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

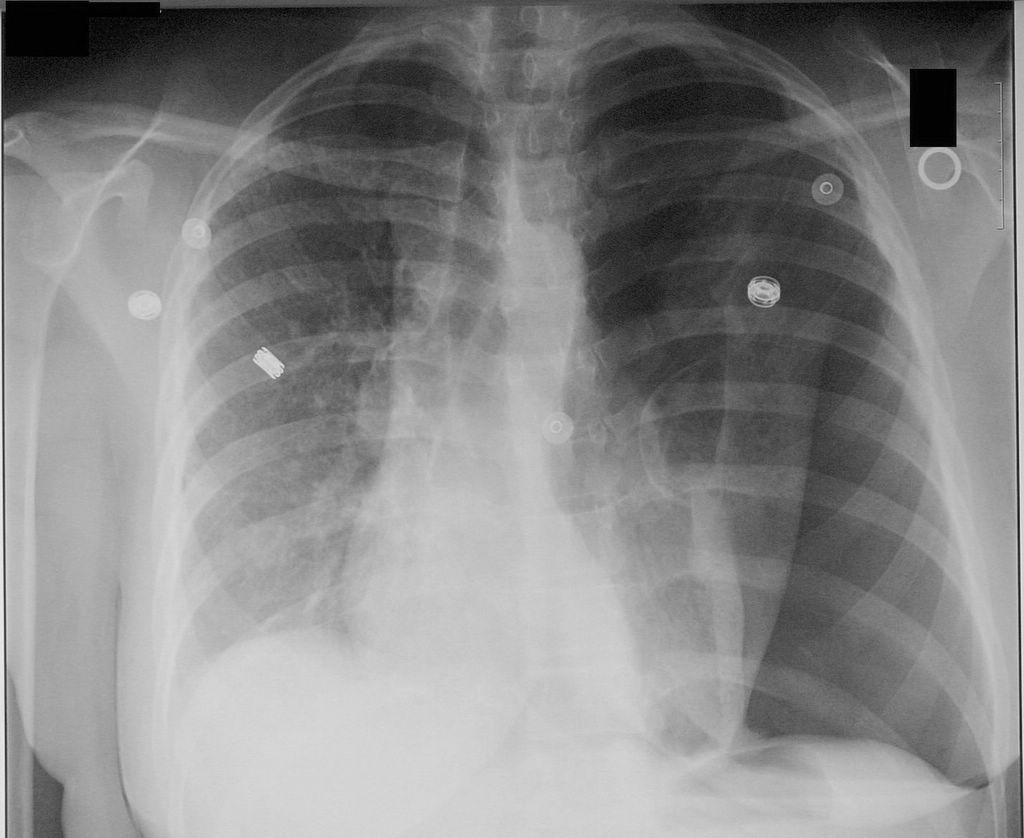

Imaging studies: Immediately proceed to needle decompression in clinically diagnosed hemodynamically unstable patients

Picture courtesy of Wikidoc.org

❑ Chest CT scanning

Picture courtesy of Wikidoc.org | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Treatment

Manage the patient with a multidisciplinary team: ❑ Consult a thoracic surgeon ❑ Consult a cardiologist | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Emergency needle decompression:

❑ Aseptic preparation

❑ Use 14-16 G intravenous cannula

❑ Listen for gush of air ❑ Watch how to do a needle decompression {{#ev:youtube|UvHJ4pjNh2Q|400|How to do a needle decompression}} Video adapted from Youtube.com Antibiotic therapy: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Admit the patient ❑ Refer the patient to respiratory specialist within 24h of admission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Insert chest drain ❑ Timing of procedures:

❑ Use image guidance

❑ Ensure aseptic technique

❑ Requirments

❑ Equipment required

Avoid complications:

❑ Intrapleural infection

❑ Wound infection

❑ Drain dislodgement and blockage

❑ Visceral injury

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Discharge and follow up ❑ All patients should be followed up by respiratory physicians | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Do`s

- Tension pneumothorax diagnosis should be made based on the history and physical examination findings.

- Serial chest radiographs every 6 hrs on the first day after injury to rule out pneumothorax is ideal.[4]

- Leave the cannula in place until bubbling is confirmed in the chest drain underwater seal system

- Suspect tension pneumothorax with blunt and penetrating trauma to the chest

- Differentiate tension pneumothorax from pericardial tamponade, and myocardial infarction.

- Suspect tension pneumothorax in patients on mechanical ventilations, who have a rapid onset of hemodynamic instability or cardiac arrest, and require increasing peak inspiratory pressures.

- Check chest tubes, as they can become plugged or malpositioned and stop functioning.

- Give adequate analgesia to patients before chest tube insertion, as the procedure is extremely painful.

- Refer the patient to respiratory specialist within 24h of admission.

Dont`s

- Don`t start using chest radiograph or CT scan unless in doubt regarding the diagnosis and when the patient's clinical condition is sufficiently stable.

- Don`t use large bore chest drains.[1]

- Don`t repeat needle aspiration unless there were technical difficulties.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J, BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group (2010). "Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010". Thorax. 65 Suppl 2: ii18–31. doi:10.1136/thx.2010.136986. PMID 20696690.

- ↑ Abolnik IZ, Lossos IS, Gillis D, Breuer R (1993). "Primary spontaneous pneumothorax in men". Am J Med Sci. 305 (5): 297–303. PMID 8484388.

- ↑ Flume PA, Strange C, Ye X, Ebeling M, Hulsey T, Clark LL (2005). "Pneumothorax in cystic fibrosis". Chest. 128 (2): 720–8. doi:10.1378/chest.128.2.720. PMID 16100160.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sharma A, Jindal P (2008). "Principles of diagnosis and management of traumatic pneumothorax". J Emerg Trauma Shock. 1 (1): 34–41. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.41789. PMC 2700561. PMID 19561940.