Adenomyosis: Difference between revisions

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

# Endomyometrial invagination of the [[endometrium]]; due to weakness of the uterine [[smooth muscles]]. | # Endomyometrial invagination of the [[endometrium]]; due to weakness of the uterine [[smooth muscles]]. | ||

# De novo development of adenomyosis from [[mullerian]] rests due to metaplasia. | # De novo development of adenomyosis from [[mullerian]] rests due to metaplasia. | ||

*The basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF) receptor/ligand system has shown to be upregulated in adenomyosis which explain the abnormal [[uterine bleeding]] and [[menorrhagia]]<ref name="pmid11528364">{{cite journal| author=Propst AM, Quade BJ, Gargiulo AR, Nowak RA, Stewart EA| title=Adenomyosis demonstrates increased expression of the basic fibroblast growth factor receptor/ligand system compared with autologous endometrium. | journal=Menopause | year= 2001 | volume= 8 | issue= 5 | pages= 368-71 | pmid=11528364 | doi=10.1097/00042192-200109000-00012 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=11528364 }} </ref>. | *The '''basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF)''' receptor/ligand system has shown to be upregulated in adenomyosis which explain the abnormal [[uterine bleeding]] and [[menorrhagia]]<ref name="pmid11528364">{{cite journal| author=Propst AM, Quade BJ, Gargiulo AR, Nowak RA, Stewart EA| title=Adenomyosis demonstrates increased expression of the basic fibroblast growth factor receptor/ligand system compared with autologous endometrium. | journal=Menopause | year= 2001 | volume= 8 | issue= 5 | pages= 368-71 | pmid=11528364 | doi=10.1097/00042192-200109000-00012 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=11528364 }} </ref>. | ||

* [[Estrogen]] and [[progesterone]] hormones play a role in the [[pathogenesis]] of adenomyosis<ref name="pmid15816354">{{cite journal| author=Green AR, Styles JA, Parrott EL, Gray D, Edwards RE, Smith AG | display-authors=etal| title=Neonatal tamoxifen treatment of mice leads to adenomyosis but not uterine cancer. | journal=Exp Toxicol Pathol | year= 2005 | volume= 56 | issue= 4-5 | pages= 255-63 | pmid=15816354 | doi=10.1016/j.etp.2004.10.001 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=15816354 }} </ref>. Other hormones such as [[oxytocin]] <ref name="pmid22999795">{{cite journal| author=Guo SW, Mao X, Ma Q, Liu X| title=Dysmenorrhea and its severity are associated with increased uterine contractility and overexpression of oxytocin receptor (OTR) in women with symptomatic adenomyosis. | journal=Fertil Steril | year= 2013 | volume= 99 | issue= 1 | pages= 231-240 | pmid=22999795 | doi=10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.038 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22999795 }} </ref>, [[FSH]]<ref name="pmid11750866">{{cite journal| author=Stewart EA| title=Gonadotropins and the uterus: is there a gonad-independent pathway? | journal=J Soc Gynecol Investig | year= 2001 | volume= 8 | issue= 6 | pages= 319-26 | pmid=11750866 | doi= | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=11750866 }} </ref>, and [[prolactin]]<ref name="pmid1853904">{{cite journal| author=Mori T, Singtripop T, Kawashima S| title=Animal model of uterine adenomyosis: is prolactin a potent inducer of adenomyosis in mice? | journal=Am J Obstet Gynecol | year= 1991 | volume= 165 | issue= 1 | pages= 232-4 | pmid=1853904 | doi=10.1016/0002-9378(91)90258-s | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=1853904 }} </ref> also contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease. | * [[Estrogen]] and [[progesterone]] hormones play a role in the [[pathogenesis]] of adenomyosis<ref name="pmid15816354">{{cite journal| author=Green AR, Styles JA, Parrott EL, Gray D, Edwards RE, Smith AG | display-authors=etal| title=Neonatal tamoxifen treatment of mice leads to adenomyosis but not uterine cancer. | journal=Exp Toxicol Pathol | year= 2005 | volume= 56 | issue= 4-5 | pages= 255-63 | pmid=15816354 | doi=10.1016/j.etp.2004.10.001 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=15816354 }} </ref>. Other hormones such as [[oxytocin]] <ref name="pmid22999795">{{cite journal| author=Guo SW, Mao X, Ma Q, Liu X| title=Dysmenorrhea and its severity are associated with increased uterine contractility and overexpression of oxytocin receptor (OTR) in women with symptomatic adenomyosis. | journal=Fertil Steril | year= 2013 | volume= 99 | issue= 1 | pages= 231-240 | pmid=22999795 | doi=10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.038 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=22999795 }} </ref>, [[FSH]]<ref name="pmid11750866">{{cite journal| author=Stewart EA| title=Gonadotropins and the uterus: is there a gonad-independent pathway? | journal=J Soc Gynecol Investig | year= 2001 | volume= 8 | issue= 6 | pages= 319-26 | pmid=11750866 | doi= | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=11750866 }} </ref>, and [[prolactin]]<ref name="pmid1853904">{{cite journal| author=Mori T, Singtripop T, Kawashima S| title=Animal model of uterine adenomyosis: is prolactin a potent inducer of adenomyosis in mice? | journal=Am J Obstet Gynecol | year= 1991 | volume= 165 | issue= 1 | pages= 232-4 | pmid=1853904 | doi=10.1016/0002-9378(91)90258-s | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=1853904 }} </ref> also contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease. | ||

*On gross [[pathology]], there is a globular enlargement of the [[myometrium]] of the [[uterus]] showing cysts filled with hemolysed [[red blood cells]] and [[sideroblasts]]<ref name="pmid16563870">{{cite journal| author=Bergeron C, Amant F, Ferenczy A| title=Pathology and physiopathology of adenomyosis. | journal=Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol | year= 2006 | volume= 20 | issue= 4 | pages= 511-21 | pmid=16563870 | doi=10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.01.016 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=16563870 }} </ref>. | *On gross [[pathology]], there is a globular enlargement of the [[myometrium]] of the [[uterus]] showing cysts filled with hemolysed [[red blood cells]] and [[sideroblasts]]<ref name="pmid16563870">{{cite journal| author=Bergeron C, Amant F, Ferenczy A| title=Pathology and physiopathology of adenomyosis. | journal=Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol | year= 2006 | volume= 20 | issue= 4 | pages= 511-21 | pmid=16563870 | doi=10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.01.016 | pmc= | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=sumsearch.org/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=16563870 }} </ref>. | ||

Revision as of 21:35, 22 May 2021

For patient information, click here

Template:DiseaseDisorder infobox

|

WikiDoc Resources for Adenomyosis |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Adenomyosis Most cited articles on Adenomyosis |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Adenomyosis |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Adenomyosis at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Adenomyosis at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Adenomyosis

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Adenomyosis Discussion groups on Adenomyosis Patient Handouts on Adenomyosis Directions to Hospitals Treating Adenomyosis Risk calculators and risk factors for Adenomyosis

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Adenomyosis |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun M.D. PhD.[2], Dina Elantably, MD[3]

Overview

Adenomyosis is a medical condition characterized by the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue (the inner lining of the uterus) within the myometrium (the thick, muscular layer of the uterus). The condition is typically found in women between the ages between 35 and 50. Patients with adenomyosis can have painful and/or profuse menses (dysmenorrhea & menorrhagia, respectively). Adenomyosis may involve the uterus focally, creating an adenomyoma, or diffusely. With diffuse involvement, the uterus becomes bulky and heavier.

Historical Perspective[1]

- Adenomyosis was first discovered by Carl von Rokitansky, a German pathologist, in 1860 when he found endometrial glands in the myometrium and designated this finding as 'cystosarcoma adenoids uterinum'.

- In 1892 the first systematic investigation of adenomyosis was carried out by 'Thomas Stephen Cullen', a gynecologist. He distinguished 3 types of adenomyoma: intramural, subperitoneal and submucous adenomyoma.

- In 1893, Kelly and Cullen described the pathogenesis of adenomyoma. The 'gradual ascendancy of Cullen’s mucosal theory' stated that endometrium invades the inner myometrium through the presence in it of ‘chinks’, or fissures.

- In 1892, Cullen described that abdominal hysterectomy is indicated for treatment as the endometrial growths are interwoven with the normal muscle of the uterus.

Classification

- Adenomyosis can be classified according to its histopathology into 2 groups:

- Diffuse adenomyosis: Uniformly enlarged boggy uterus.

- Focal adenomyosis (adenomyoma): Grossly it resembles fibroid but without a surrounding pseudocapsule.

- Other variants of adenomyosis include juvenile cystic adenomyosis; which is the presence of endometrial cysts > 1cm in diameter within the myometrium. It is usually seen in young women <30 years old [2].

Pathophysiology

- The pathogenesis of Adenomyosis is poorly understood. There two theories that explain the possible pathogenesis[3]:

- Endomyometrial invagination of the endometrium; due to weakness of the uterine smooth muscles.

- De novo development of adenomyosis from mullerian rests due to metaplasia.

- The basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF) receptor/ligand system has shown to be upregulated in adenomyosis which explain the abnormal uterine bleeding and menorrhagia[4].

- Estrogen and progesterone hormones play a role in the pathogenesis of adenomyosis[5]. Other hormones such as oxytocin [6], FSH[7], and prolactin[8] also contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease.

- On gross pathology, there is a globular enlargement of the myometrium of the uterus showing cysts filled with hemolysed red blood cells and sideroblasts[9].

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, there are endometrial glands, and stroma surrounded by hypertrophic smooth muscle bundles haphazardly scattered within the myometrium[9].

{{#ev:youtube|nOCtpIwCZ-Y}}

Causes

The cause of adenomyosis is unknown, although it has been associated with any sort of uterine trauma that may break the barrier between the endometrium and myometrium, such as:

Differential Diagnosis of Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis is a cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and can result in infertility. There are several diseases which can result in excessive uterine bleeding and the following table is a description of various causes of excessive uterine bleeding.

| Clinical Features | Physical Examination | Diagnostic Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endometriosis |

|

|

|

| Adenomyosis[10] |

|

|

|

| Submucous uterine leiomyomas[11] |

|

|

|

| Pelvic Inflammatory disease[12] |

|

|

|

| Pelvic congestion Syndrome[13] |

|

|

|

Epidemiology and Demographics

- It is generally estimated that adenomyosis is present in 20-35% of women[14].

- The incidence and prevalence of adenomyosis are, however, difficult to be accurately estimated and biased by studying only women undergoing hysterectomy, so the total population of women having the disease is not known[15].

Age

- Adenomyosis is more commonly observed among women aged 40-50 years in those undergoing hysterectomy for diagnosis[9].

- Adenomyosis is less commonly diagnosed in adolescents who undergo pelvic imaging by transvaginal ultrasound or MRI rather than a hysterectomy for diagnosis[10].

Race

- There is no racial predilection for adenomyosis.

- Almost all cases of adenomyosis present in multiparous women, however there is no clear causal relationship between multiparty and the development of the disease[9]

Risk Factors

- Similar to the epidemiology, the risk factors of adenomyosis are unknown and difficult to be accurately determined as diagnosis is based on examining pathological specimens only in women undergoing hysterectomy[15].

- Adenomyosis often coexists with other pelvic diseases namely endometriosis and leiomyoma, so it is unknown whether it exhibits specific risk factors[10].

- Prior uterine surgery has been shown to be a possible risk factor for the development of adenomyosis[16].

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

- Early clinical features of adenomyosis include dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, and chronic pelvic pain.

- Some reported complications of adenomyosis are preterm birth and miscarriage in young women diagnosed by pelvic imaging[17]. The relationship of adenomyosis to infertility is controversial[18].

- Prognosis is generally good as surgical treatment by hysterectomy is often curable unless there is another associated uterine pathology that requires further attention. There is no increased risk for secondary development of endometrial carcinoma.

Diagnosis

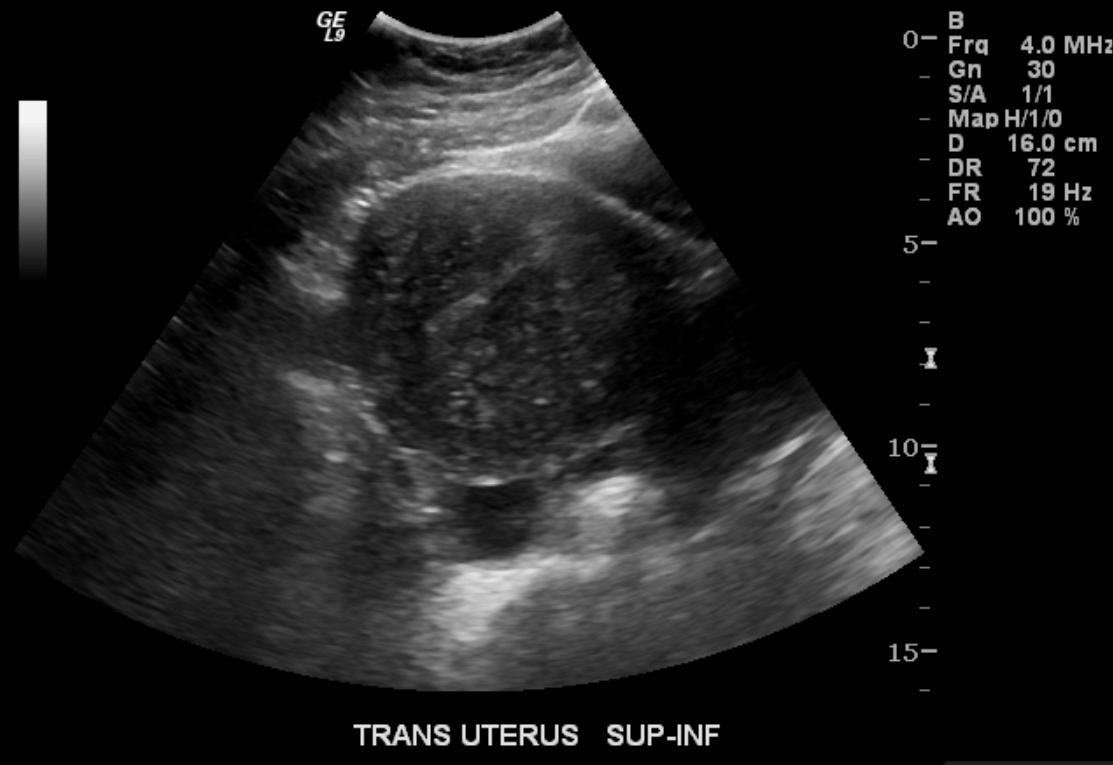

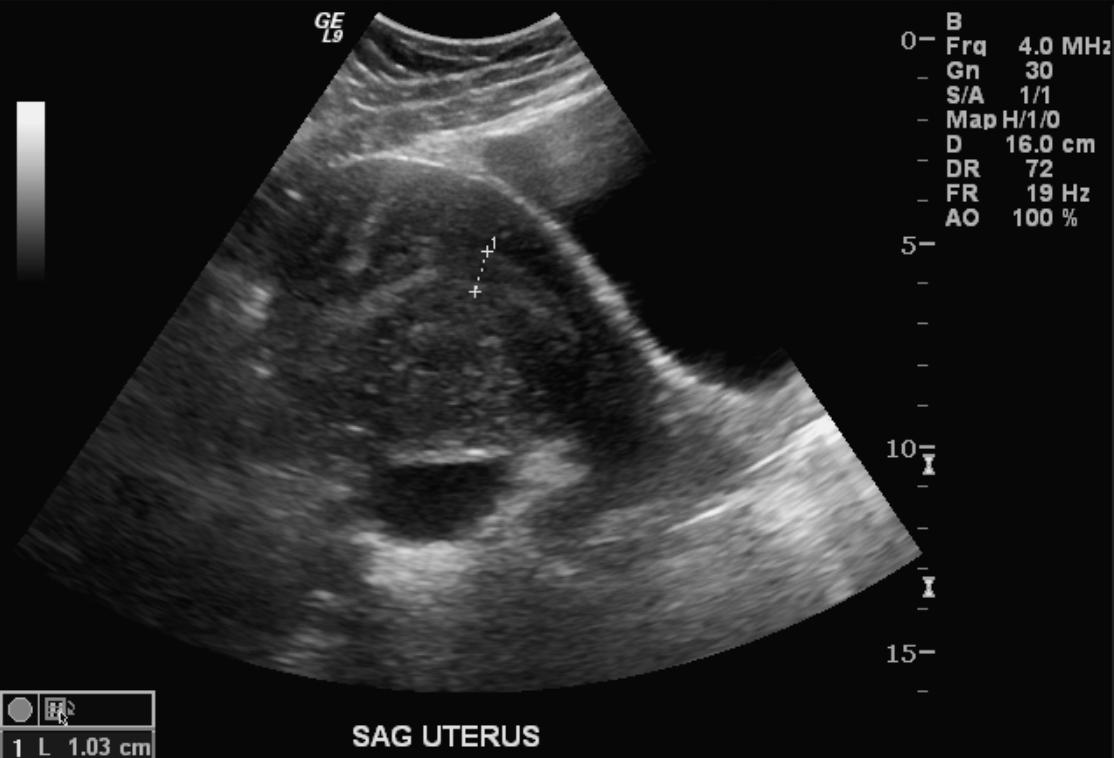

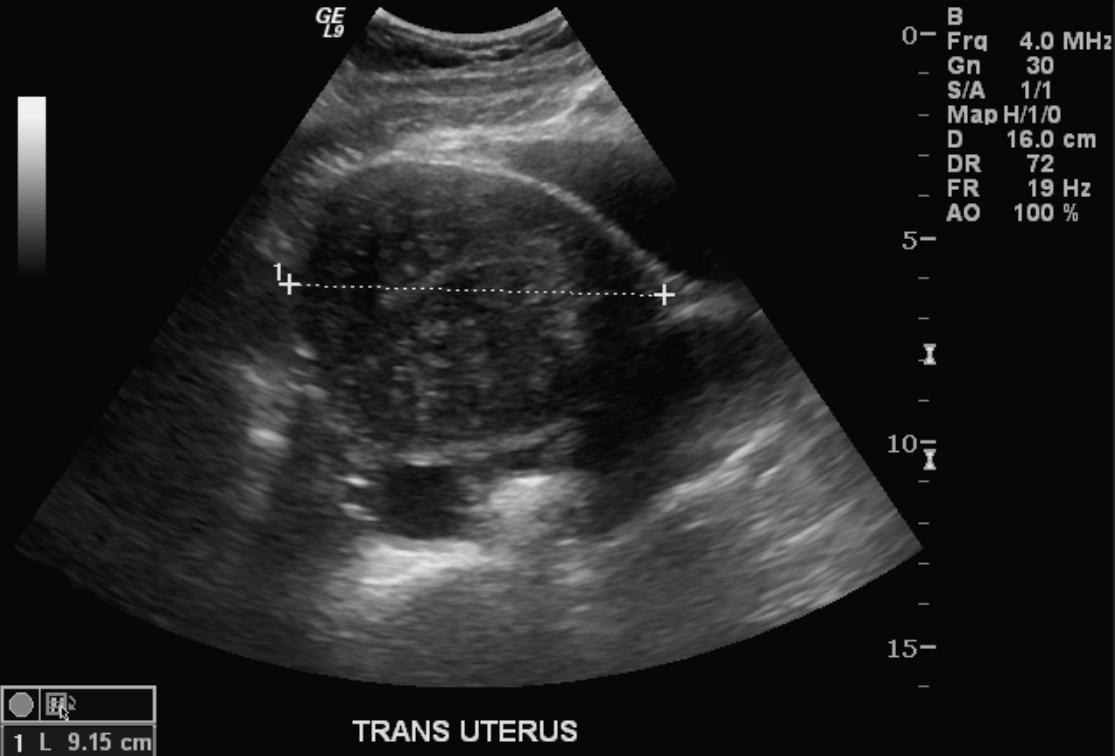

The uterus may be imaged using ultrasound (US) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Transvaginal ultrasound is the most cost effective and most available. Either modality will show an enlarged uterus. On ultrasound, the uterus will have a heterogeneous texture, without the focal well-defined masses that characterize uterine fibroids.

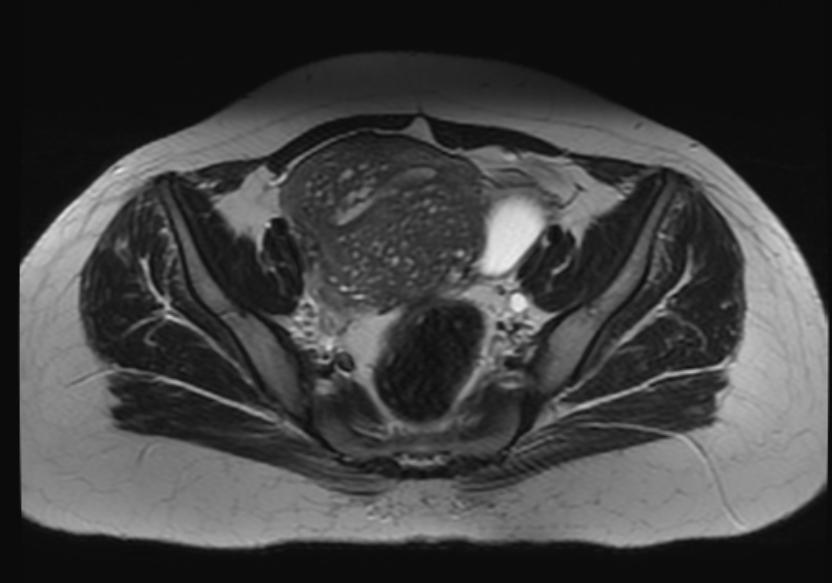

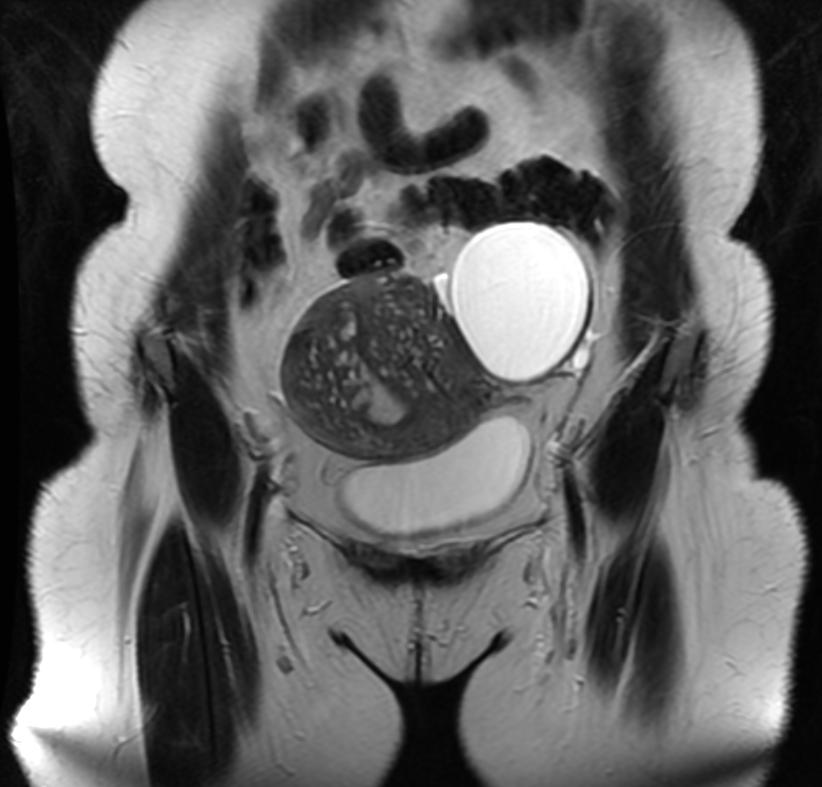

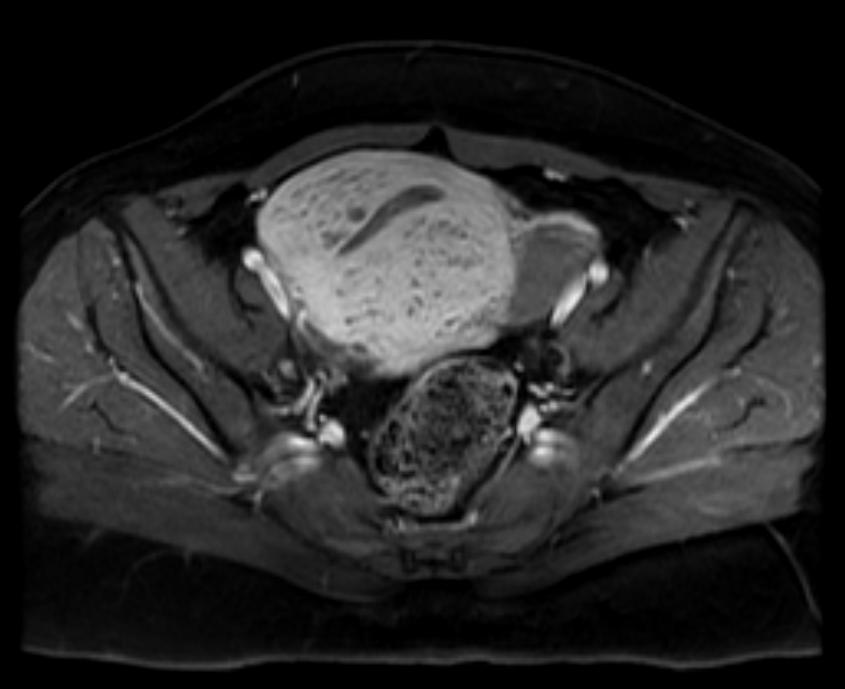

MRI provides better diagnostic capability due to the increased spatial and contrast resolution, and to not being limited by the presence of bowel gas or calcified uterine fibroids (as is ultrasound). In particular, MR is better able to differentiate adenomyosis from multiple small uterine fibroids. The uterus will have a thickened junctional zone with diminished signal on both T1 and T2 weighted sequences due to susceptibility effects of iron deposition due to chronic microhemorrhage. A thickness of the junctional zone greater than 10 to 12 mm (depending on who you read) is diagnostic of adenomyosis (<8 mm is normal). Interspersed within the thickened, hypointense signal of the junctional zone, one will often see foci of hyperintensity (brightness) on the T2 weighted scans representing small cystically dilatated glands or more acute sites of microhemorrhage.

MR can be used to classify adenomyosis based on the depth of penetration of the ectopic endometrium into the myometrium.

Diagnostic Criteria

- The diagnosis of [disease name] is made when at least [number] of the following [number] diagnostic criteria are met:

- [criterion 1]

- [criterion 2]

- [criterion 3]

- [criterion 4]

Symptoms

- [Disease name] is usually asymptomatic.

- Symptoms of [disease name] may include the following:

- [symptom 1]

- [symptom 2]

- [symptom 3]

- [symptom 4]

- [symptom 5]

- [symptom 6]

Physical Examination

- Patients with [disease name] usually appear [general appearance].

- Physical examination may be remarkable for:

- [finding 1]

- [finding 2]

- [finding 3]

- [finding 4]

- [finding 5]

- [finding 6]

Ultrasonography

- Typical appearances of adenomyosis at transvaginal ultrasound include poorly marginated hypoechoic and heterogeneous areas within the myometrium, myometrial cysts, and a globular or enlarged uterus with asymmetry.

-

US: Adenomyosis

-

US: Adenomyosis

-

US: Adenomyosis

Computed Tomography

-

CT: Adenomyosis

-

CT: Adenomyosis

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- Adenomyosis appears as either diffuse or focal thickening (greater than 12 mm )of the junctional zone forming an ill-defined area of low signal intensity, occasionally with embedded bright foci on T2-weighted images.

- Histologically, areas of low signal intensity correspond to smooth muscle hyperplasia, and bright foci on T2-weighted images correspond to islands of ectopic endometrial tissue and cystic dilatation of glands.

-

T2: Adenomyosis

-

T2: Adenomyosis

-

T2: Adenomyosis

-

T1 fat sat contrast: Adenomyosis

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- There is no treatment for [disease name]; the mainstay of therapy is supportive care.

- The mainstay of therapy for [disease name] is [medical therapy 1] and [medical therapy 2].

- [Medical therapy 1] acts by [mechanism of action 1].

- Response to [medical therapy 1] can be monitored with [test/physical finding/imaging] every [frequency/duration].

Surgery

- Surgery is the mainstay of therapy for [disease name].

- [Surgical procedure] in conjunction with [chemotherapy/radiation] is the most common approach to the treatment of [disease name].

- [Surgical procedure] can only be performed for patients with [disease stage] [disease name].

Prevention

- There are no primary preventive measures available for [disease name].

- Effective measures for the primary prevention of [disease name] include [measure1], [measure2], and [measure3].

- Once diagnosed and successfully treated, patients with [disease name] are followed-up every [duration]. Follow-up testing includes [test 1], [test 2], and [test 3].

Treatment options range from use of NSAIDS & hormonal suppression for symptomatic relief, with hysterectomy the only permanent cure option. Women with Adenomyosis fail endometrial ablation because the ablation only affects the surface endometrial tissue, not the tissue that has grown into the muscle lining. This remaining tissue is still viable and will continue to cause pain. The result of failed ablation due to Adenomyosis is hysterectomy.

Those that believe an excess of estrogen is the cause or adenomyosis, or that it aggravates the symptoms, recommend avoiding products with xenoestrogens and/or recommend taking natural progesterone supplements.

References

- ↑ Benagiano G, Brosens I (2006). "History of adenomyosis". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 20 (4): 449–63. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.01.007. PMID 16515887.

- ↑ Takeuchi H, Kitade M, Kikuchi I, Kumakiri J, Kuroda K, Jinushi M (2010). "Diagnosis, laparoscopic management, and histopathologic findings of juvenile cystic adenomyoma: a review of nine cases". Fertil Steril. 94 (3): 862–8. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.05.010. PMID 19539912.

- ↑ Ferenczy A (1998). "Pathophysiology of adenomyosis". Hum Reprod Update. 4 (4): 312–22. doi:10.1093/humupd/4.4.312. PMID 9825847.

- ↑ Propst AM, Quade BJ, Gargiulo AR, Nowak RA, Stewart EA (2001). "Adenomyosis demonstrates increased expression of the basic fibroblast growth factor receptor/ligand system compared with autologous endometrium". Menopause. 8 (5): 368–71. doi:10.1097/00042192-200109000-00012. PMID 11528364.

- ↑ Green AR, Styles JA, Parrott EL, Gray D, Edwards RE, Smith AG; et al. (2005). "Neonatal tamoxifen treatment of mice leads to adenomyosis but not uterine cancer". Exp Toxicol Pathol. 56 (4–5): 255–63. doi:10.1016/j.etp.2004.10.001. PMID 15816354.

- ↑ Guo SW, Mao X, Ma Q, Liu X (2013). "Dysmenorrhea and its severity are associated with increased uterine contractility and overexpression of oxytocin receptor (OTR) in women with symptomatic adenomyosis". Fertil Steril. 99 (1): 231–240. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.08.038. PMID 22999795.

- ↑ Stewart EA (2001). "Gonadotropins and the uterus: is there a gonad-independent pathway?". J Soc Gynecol Investig. 8 (6): 319–26. PMID 11750866.

- ↑ Mori T, Singtripop T, Kawashima S (1991). "Animal model of uterine adenomyosis: is prolactin a potent inducer of adenomyosis in mice?". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 165 (1): 232–4. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(91)90258-s. PMID 1853904.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Bergeron C, Amant F, Ferenczy A (2006). "Pathology and physiopathology of adenomyosis". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 20 (4): 511–21. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.01.016. PMID 16563870.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Parker JD, Leondires M, Sinaii N, Premkumar A, Nieman LK, Stratton P (2006). "Persistence of dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pain after optimal endometriosis surgery may indicate adenomyosis". Fertil Steril. 86 (3): 711–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.030. PMID 16782099.

- ↑ Donnez J, Donnez O, Matule D, Ahrendt HJ, Hudecek R, Zatik J; et al. (2016). "Long-term medical management of uterine fibroids with ulipristal acetate". Fertil Steril. 105 (1): 165–173.e4. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.032. PMID 26477496.

- ↑ Ross J, Judlin P, Jensen J, International Union against sexually transmitted infections (2014). "2012 European guideline for the management of pelvic inflammatory disease". Int J STD AIDS. 25 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1177/0956462413498714. PMID 24216035.

- ↑ Rozenblit AM, Ricci ZJ, Tuvia J, Amis ES (2001). "Incompetent and dilated ovarian veins: a common CT finding in asymptomatic parous women". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 176 (1): 119–22. doi:10.2214/ajr.176.1.1760119. PMID 11133549.

- ↑ Vercellini P, Viganò P, Somigliana E, Daguati R, Abbiati A, Fedele L (2006). "Adenomyosis: epidemiological factors". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 20 (4): 465–77. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.01.017. PMID 16563868.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Abbott JA (2017). "Adenomyosis and Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (AUB-A)-Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 40: 68–81. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.09.006. PMID 27810281.

- ↑ Panganamamula UR, Harmanli OH, Isik-Akbay EF, Grotegut CA, Dandolu V, Gaughan JP (2004). "Is prior uterine surgery a risk factor for adenomyosis?". Obstet Gynecol. 104 (5 Pt 1): 1034–8. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000143264.59822.73. PMID 15516398.

- ↑ Horton J, Sterrenburg M, Lane S, Maheshwari A, Li TC, Cheong Y (2019). "Reproductive, obstetric, and perinatal outcomes of women with adenomyosis and endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum Reprod Update. 25 (5): 592–632. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmz012. PMID 31318420.

- ↑ Maheshwari A, Gurunath S, Fatima F, Bhattacharya S (2012). "Adenomyosis and subfertility: a systematic review of prevalence, diagnosis, treatment and fertility outcomes". Hum Reprod Update. 18 (4): 374–92. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms006. PMID 22442261.

Additional Resources

- Atri M, Reinhold C, Mehio AR. Adenomyosis: US features with histologic correlation in an in-vitro study. Radiology. Jun 2000;215(3):783-90.

- Batzer FR, Hansen L. Bizarre sonographic appearance of an adenomyoma and its presentation. J Ultrasound Med. Aug 1996;15(8):599-602.

- Bazot M, Daraï E. [Evaluation of pelvic endometriosis: the role of MRI.]. J Radiol. Nov 2008;89(11 Pt 1):1695-6.

- Byun JY, Kim SE, Choi BG, et al. Diffuse and focal adenomyosis: MR imaging findings. Radiographics. Oct 1999;19 Spec No:S161-70.

- Chiang CH, Chang MY, Hsu JJ. Tumor vascular pattern and blood flow impedance in the differential diagnosis of leiomyoma and adenomyosis by color Doppler sonography. J Assist Reprod Genet. May 1999;16(5):268-75.

- Guilbeault H, Wilson SR, Lickrish GM. Massive uterine enlargement with necrosis: an unusual manifestation of adenomyosis. J Ultrasound Med. Apr 1994;13(4):326-8.

- Haimovici JB, Tempany CM. MR of the female pelvis: benign disease. Appl Radiol. Jun 1994;7:21.

- Huang HY. Medical treatment of endometriosis. Chang Gung Med J. Sep-Oct 2008;31(5):431-40.

- Iribarne C, Plaza J, De la Fuente P, et al. Intramyometrial cystic adenomyosis. J Clin Ultrasound. Jun 1994;22(5):348-50.

- Jarlot C, Anglade E, Paillocher N, Moreau D, Catala L, Aubé C. [MR imaging features of deep pelvic endometriosis: correlation with laparoscopy.]. J Radiol. Nov 2008;89(11 Pt 1):1745-54.

- Kang S, Turner DA, Foster GS, et al. Adenomyosis: specificity of 5 mm as the maximum normal uterine junctional zone thickness in MR images. AJR Am J Roentgenol. May 1996;166(5):1145-50.

- Kim MD, Lee HS, Lee MH, Kim HJ, Cho JH, Cha SH. Long-term results of symptomatic fibroids treated with uterine artery embolization: In conjunction with MR evaluation. Eur J Radiol. Dec 10 2008;

- Ostrzenski A. Extensive iatrogenic adenomyosis after laparoscopic myomectomy. Fertil Steril. Jan 1998;69(1):143-5.

- Piketty M, Chopin N, Dousset B, Millischer-Bellaische AE, Roseau G, Leconte M, et al. Preoperative work-up for patients with deeply infiltrating endometriosis: transvaginal ultrasonography must definitely be the first-line imaging examination. Hum Reprod. Dec 17 2008;

- Piketty M, Chopin N, Dousset B, Millischer-Bellaische AE, Roseau G, Leconte M, et al. Preoperative work-up for patients with deeply infiltrating endometriosis: transvaginal ultrasonography must definitely be the first-line imaging examination. Hum Reprod. Dec 17 2008;

- Reinhold C, Atri M, Mehio A, et al. Diffuse uterine adenomyosis: morphologic criteria and diagnostic accuracy of endovaginal sonography. Radiology. Dec 1995;197(3):609-14.

- Reinhold C, Tafazoli F, Mehio A, et al. Uterine adenomyosis: endovaginal US and MR imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Radiographics. Oct 1999;19 Spec No:S147-60.

- Tamai K, Koyama T, Umeoka S, et al. Spectrum of MR features in adenomyosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. Aug 2006;20(4):583-602.

- Tamai K, Togashi K, Ito T, et al. MR imaging findings of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathologic features and diagnostic pitfalls. Radiographics. Jan-Feb 2005;25(1):21-40.

- Utsunomiya D, Notsute S, Hayashida Y, et al. Endometrial carcinoma in adenomyosis: assessment of myometrial invasion on T2-weighted spin-echo and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images. AJR Am J Roentgenol. Feb 2004;182(2):399-404.

Template:Diseases of the pelvis, genitals and breasts