Chondrosarcoma pathophysiology

|

Chondrosarcoma Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Chondrosarcoma pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Chondrosarcoma pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Chondrosarcoma pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Rohan A. Bhimani, M.B.B.S., D.N.B., M.Ch.[2]

Overview

The exact pathogenesis of chondrosarcoama is not fully understood. Multiple genes have been implicated in pathogenesis of chondrosarcoma. Cytogenetic analysis of chondrosarcomas revealed that structural abnormalities of chromosomes 1, 6, 9, 12 and 15 and numerical abnormalities of chromosomes 5, 7, 8 and 18 are most frequent associated. Anomalies associated with chromosome 9(9p12-22) are more commonly seen in central chondrosarcomas. Germline mutations in the exostosin (EXT1 or EXT2) genes, TP53 or pRb pathway, isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 and isocitrate dehydrogenase- 2 genes and gene encoding the receptor for parathyroid have been implicated. On gross pathology, greyish-white lobulated mass, necrosis, calcification, and mucoid degeneration are characteristic findings of chondrosarcoma. On microscopic histopathological analysis abnormal cartilage, increased cellularity, and nuclear atypia are characteristic findings of chondrosarcoma. Chondrosarcoma may be divided into three grades based on cancer cells morphology under microscope and growth rate of tumor.

Pathophysiology

Physiology

- Cartilaginous tumors are seen in bones that arise from enchondral ossification.[1]

- There is hypertrophy of the resting zone of chondrocytes due to proliferation and differentiation within the normal growth plate.[1]

- These cells the undergo apoptosis resulting in invasion of vessels and osteoblasts that start to form bone and lead to longitudinal bone growth.

- This physiologic process is regulated by components of the Indian hedgehog (IHH)/parathyroid hormone related (PTHRP) protein signaling pathway.

Pathogenesis

- The exact pathogenesis of chondrosarcoma is not full understood.[2]

- Multiple genes have been implicated in pathogenesis of chondrosarcoma.

Genetics

- Cytogenetic analysis of chondrosarcomas revealed that structural abnormalities of chromosomes 1, 6, 9, 12 and 15.[3]

- Also, numerical abnormalities of chromosomes 5, 7, 8 and 18 were most frequent associated with chondrosarcoma.[4]

- Anomalies associated with chromosome 9(9p12-22) are more commonly seen in central chondrosarcomas.[5]

- Patients with multiple osteochondromas seem to have germline mutations in the exostosin (EXT1 or EXT2) genes.[6]

- This result is decreased EXT expression and decreased biosynthesis and release of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), which are essential for cell signaling through IHH/PTHLH pathways.[7][8][9]

- This in turn decreases normal chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation within the normal human growth plate.

- Furthermore, the genetic mutations in the TP53 or pRb pathway are implied in the malignant transformation from osteochondroma to secondary peripheral chondrosarcoma.

- In enchondromas and central chondrosarcomas, point mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 and isocitrate dehydrogenase - 2 genes (IDH1 and IDH2) have been suggested.

- In addition, the Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome are also result of somatic mosaic mutations in IDH1 and IDH2. [10]

- Isocitrate dehydrogenase is the necessary enzyme required for conversion of isocitrate to alpha-ketoglutarate in the tricarboxylic acid cycle.

- Mutations in IDH1 and IDH2 cause elevated levels of the oncometabolite D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D-2-HG) which promotes chondrogenesis and inhibit osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells as well as causes DNA hypermethylation and histone modification, all resulting in decreased differentiation.[11]

- A missense mutation (R150C) in the gene encoding the receptor for PTHRP (PTH-1 receptor or PTH1R) has been associated to enchondromatosis in patients with Ollier disease, and decreased receptor function.[12][13][14]

- Low-grade chondrosarcomas are near-diploid and have very few karyotypic abnormalities.[15]

- On the other hand, high grade chondrosarcomas are aneuploid and have complex karyotypes.[15]

- The progression of chondrosarcoma has been linked to the CDKN2A (p16) tumor suppressor gene present at 9p21 and by mutation in p53.[16][17]

- Mutations in COL2A1 have also been hypothesized in pathogenesis of chondrosarcomas.[18]

- In addition, amplification of the c-myc and fos/jun protien has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of chondrosarcoma.[19][20]

- A specific HEY1-NCOA2 fusion product due to an intra-chromosomal rearrangement of chromosome arm 8q result in mesenchymal chondrosarcoma.

- With extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas, the t(9;22)(q22;q12) translocation is common.[21]

Gross Pathology

Characteristic features of chondrosarcoma on gross pathology are:[22][23]

- Greyish-white lobulated mass

- Necrosis

- Calcification

- Mucoid degeneration

Microscopic Pathology

In general chondrosarcomas are multi-lobulated (due to hyaline cartilage nodules) with central high water content and peripheral enchondral ossification. Characteristic features on microscopic analysis are variable depending on the chondrosarcoma subtype:

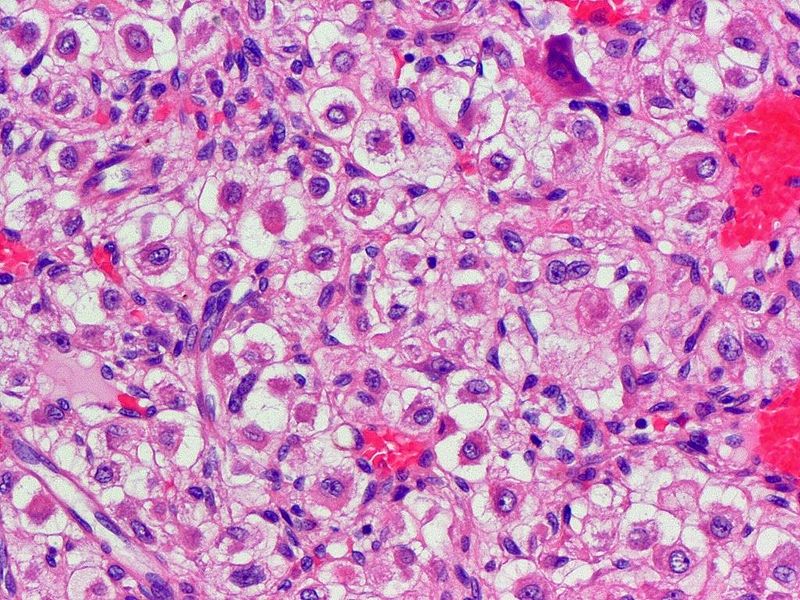

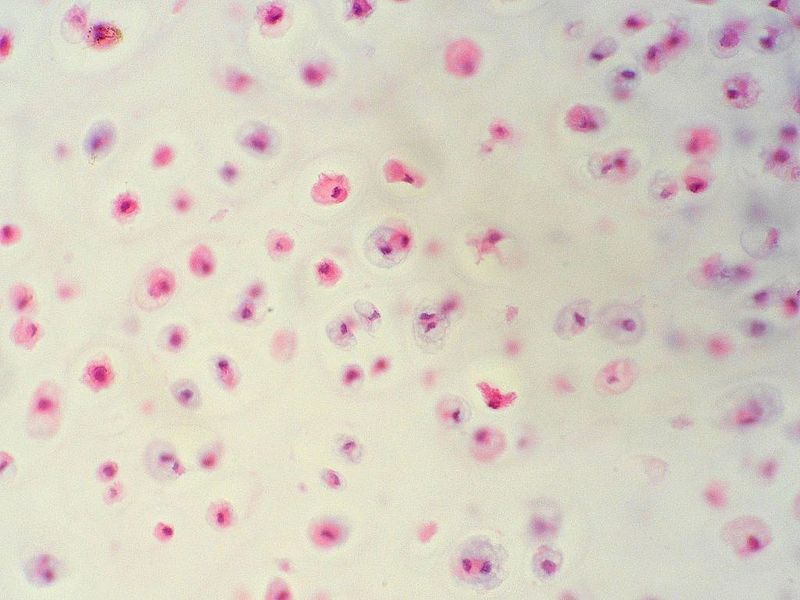

Clear cell chondrosarcoma

- Lobules of uniform to polymorphic densely-packed large cells.[24][25][26]

- Well defined pushing borders.

- Clear to intensively acidophilic granular cytoplasm with vacuoles.

- Central nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli.

- Low mitotic rate.

- Clear cell areas lack production of hyaline chondroid matrix.

- Areas with osteoclast-type giant cells mixed with small trabeculae of reactive bone.

- May contain conventional low-grade chondrosarcoma.

- May have secondary aneurysmal bone cyst changes.

|

|

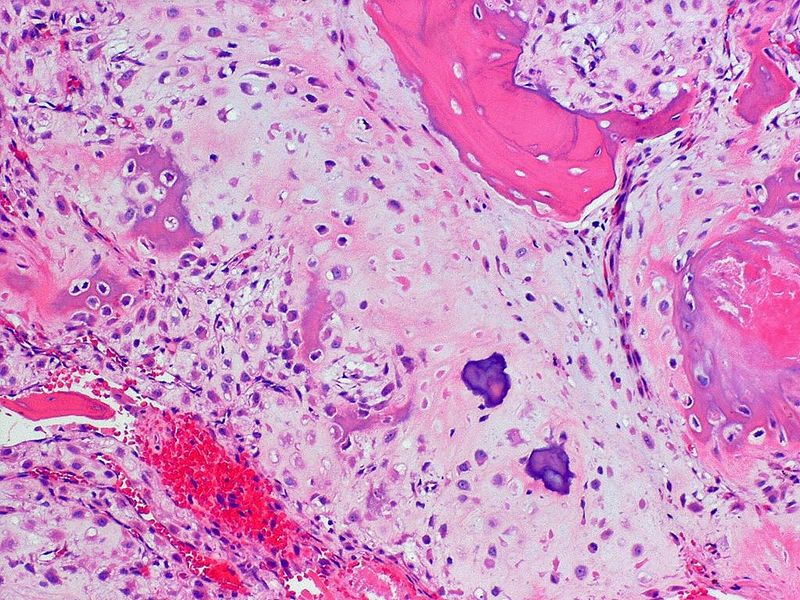

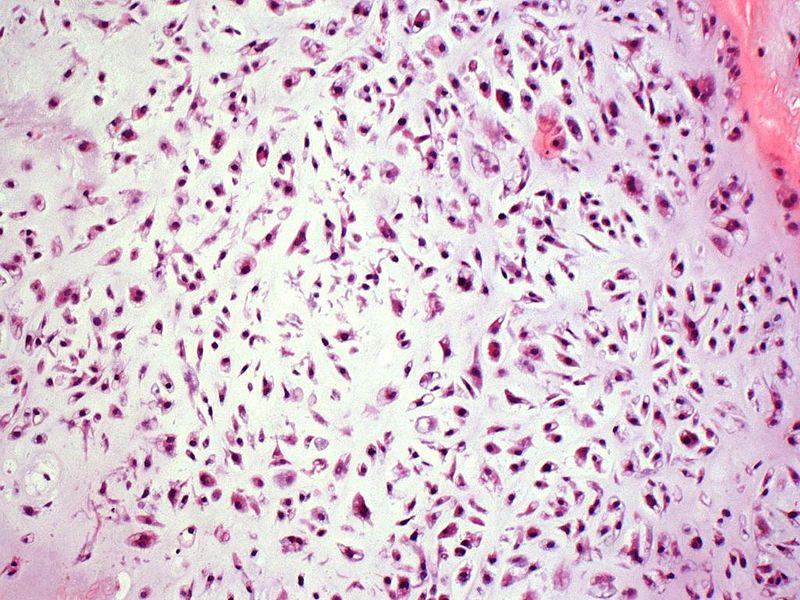

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma

Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma is a malignant tumor with a characteristic biphasic pattern:[27][28][29]

- Poorly differentiated small round blue cells

- Islands of well-differentiated hyaline cartilage

- Progressive maturation of cartilage towards the center

- Central calcification or bone formation

- Can have a hemangiopericytomatous vascular pattern.

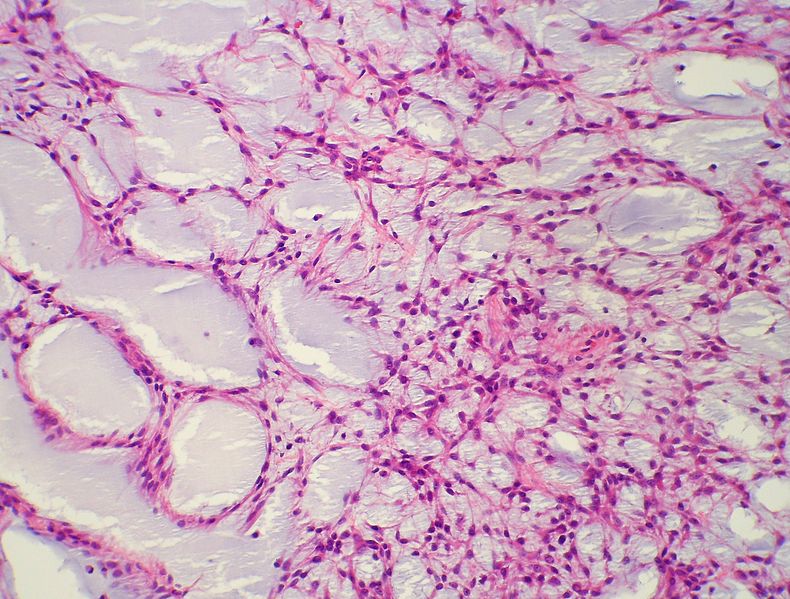

Myxoid chondrosarcoma

|

|

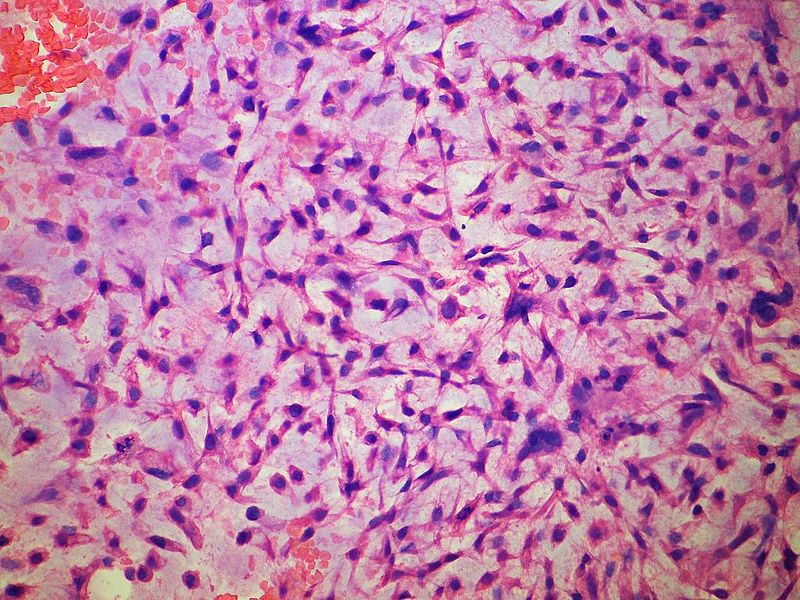

Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma

- Poorly differentiated mesenchymal malignancy.[32]

- Well-differentiated cartilaginous component

Histological Grading

- Chondrosarcomas can be classified into the following three histologic grades, depending on findings of cellularity, atypia, and pleomorphism:[33][34]

Grade 1

- Chondrosarcoma grows relatively slowly, has cells whose histological appearance is quite similar to cells of normal cartilage.

- Mostly chondroid matrix, little if any myxoid.

- Mild-to-moderate increase of cellularity +/- binucleated cells.

- Have much less aggressive invasive and metastatic properties.

|

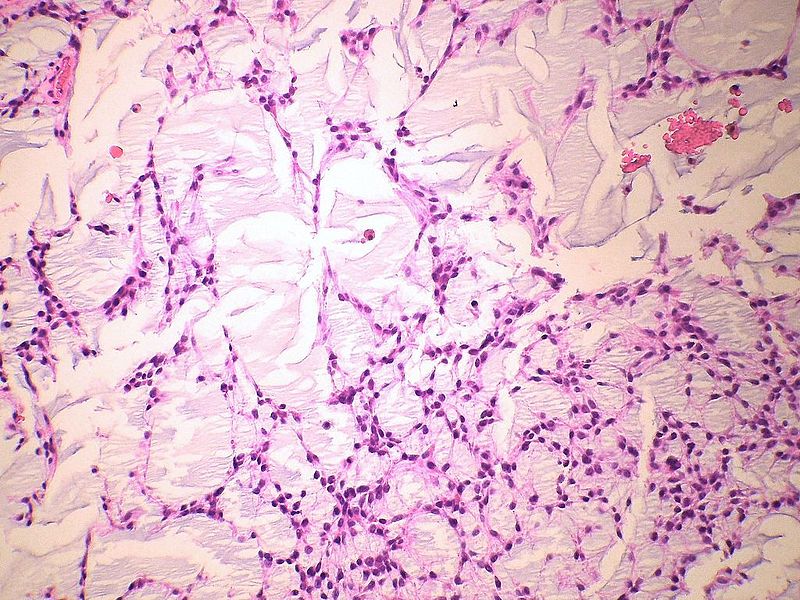

Grade 2

- Intermediate grade chondrosarcoma

- Little chondroid matrix, necrosis and more common prominent myxoid.

|

Grade 3

- Grade 3 chondrosarcoma is increasingly faster-growing cancer, with more varied and abnormal-looking cells.

- Characterized by myxoid stroma, nuclear pleomorphism and mitoses.

- Absent chondroid matrix.

- These are much more likely to infiltrate surrounding tissues, lymph nodes, and organs.

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bovée JV, Hogendoorn PC, Wunder JS, Alman BA (2010). "Cartilage tumours and bone development: molecular pathology and possible therapeutic targets". Nat Rev Cancer. 10 (7): 481–8. doi:10.1038/nrc2869. PMID 20535132.

- ↑ Peabody, Terrance (2014). Orthopaedic oncology : primary and metastatic tumors of the skeletal system. Cham: Springer. ISBN 9783319073224.

- ↑ Bovée JV, Cleton-Jansen AM, Kuipers-Dijkshoorn NJ, van den Broek LJ, Taminiau AH, Cornelisse CJ; et al. (1999). "Loss of heterozygosity and DNA ploidy point to a diverging genetic mechanism in the origin of peripheral and central chondrosarcoma". Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 26 (3): 237–46. PMID 10502322.

- ↑ Bovée JV, Cleton-Jansen AM, Rosenberg C, Taminiau AH, Cornelisse CJ, Hogendoorn PC (1999). "Molecular genetic characterization of both components of a dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma, with implications for its histogenesis". J Pathol. 189 (4): 454–62. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199912)189:4<454::AID-PATH467>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 10629543.

- ↑ Bovée JV, Sciot R, Dal Cin P, Debiec-Rychter M, van Zelderen-Bhola SL, Cornelisse CJ; et al. (2001). "Chromosome 9 alterations and trisomy 22 in central chondrosarcoma: a cytogenetic and DNA flow cytometric analysis of chondrosarcoma subtypes". Diagn Mol Pathol. 10 (4): 228–35. PMID 11763313.

- ↑ de Andrea CE, Reijnders CM, Kroon HM, de Jong D, Hogendoorn PC, Szuhai K; et al. (2012). "Secondary peripheral chondrosarcoma evolving from osteochondroma as a result of outgrowth of cells with functional EXT". Oncogene. 31 (9): 1095–104. doi:10.1038/onc.2011.311. PMID 21804604.

- ↑ Hameetman L, Szuhai K, Yavas A, Knijnenburg J, van Duin M, van Dekken H; et al. (2007). "The role of EXT1 in nonhereditary osteochondroma: identification of homozygous deletions". J Natl Cancer Inst. 99 (5): 396–406. doi:10.1093/jnci/djk067. PMID 17341731.

- ↑ McCormick C, Leduc Y, Martindale D, Mattison K, Esford LE, Dyer AP; et al. (1998). "The putative tumour suppressor EXT1 alters the expression of cell-surface heparan sulfate". Nat Genet. 19 (2): 158–61. doi:10.1038/514. PMID 9620772.

- ↑ Hameetman L, David G, Yavas A, White SJ, Taminiau AH, Cleton-Jansen AM; et al. (2007). "Decreased EXT expression and intracellular accumulation of heparan sulphate proteoglycan in osteochondromas and peripheral chondrosarcomas". J Pathol. 211 (4): 399–409. doi:10.1002/path.2127. PMID 17226760.

- ↑ Pansuriya TC, van Eijk R, d'Adamo P, van Ruler MA, Kuijjer ML, Oosting J; et al. (2011). "Somatic mosaic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are associated with enchondroma and spindle cell hemangioma in Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome". Nat Genet. 43 (12): 1256–61. doi:10.1038/ng.1004. PMC 3427908. PMID 22057234.

- ↑ Amary MF, Bacsi K, Maggiani F, Damato S, Halai D, Berisha F; et al. (2011). "IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours". J Pathol. 224 (3): 334–43. doi:10.1002/path.2913. PMID 21598255.

- ↑ Bovée JV, van den Broek LJ, Cleton-Jansen AM, Hogendoorn PC (2000). "Up-regulation of PTHrP and Bcl-2 expression characterizes the progression of osteochondroma towards peripheral chondrosarcoma and is a late event in central chondrosarcoma". Lab Invest. 80 (12): 1925–34. PMID 11140704.

- ↑ Rozeman LB, Hameetman L, Cleton-Jansen AM, Taminiau AH, Hogendoorn PC, Bovée JV (2005). "Absence of IHH and retention of PTHrP signalling in enchondromas and central chondrosarcomas". J Pathol. 205 (4): 476–82. doi:10.1002/path.1723. PMID 15685701.

- ↑ Hopyan S, Gokgoz N, Poon R, Gensure RC, Yu C, Cole WG; et al. (2002). "A mutant PTH/PTHrP type I receptor in enchondromatosis". Nat Genet. 30 (3): 306–10. doi:10.1038/ng844. PMID 11850620.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Tallini G, Dorfman H, Brys P, Dal Cin P, De Wever I, Fletcher CD; et al. (2002). "Correlation between clinicopathological features and karyotype in 100 cartilaginous and chordoid tumours. A report from the Chromosomes and Morphology (CHAMP) Collaborative Study Group". J Pathol. 196 (2): 194–203. doi:10.1002/path.1023. PMID 11793371.

- ↑ van Beerendonk HM, Rozeman LB, Taminiau AH, Sciot R, Bovée JV, Cleton-Jansen AM; et al. (2004). "Molecular analysis of the INK4A/INK4A-ARF gene locus in conventional (central) chondrosarcomas and enchondromas: indication of an important gene for tumour progression". J Pathol. 202 (3): 359–66. doi:10.1002/path.1517. PMID 14991902.

- ↑ Rozeman LB, Hogendoorn PC, Bovée JV (2002). "Diagnosis and prognosis of chondrosarcoma of bone". Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2 (5): 461–72. doi:10.1586/14737159.2.5.461. PMID 12271817.

- ↑ Tarpey PS, Behjati S, Cooke SL, Van Loo P, Wedge DC, Pillay N; et al. (2013). "Frequent mutation of the major cartilage collagen gene COL2A1 in chondrosarcoma". Nat Genet. 45 (8): 923–6. doi:10.1038/ng.2668. PMC 3743157. PMID 23770606.

- ↑ Castresana JS, Barrios C, Gómez L, Kreicbergs A (1992). "Amplification of the c-myc proto-oncogene in human chondrosarcoma". Diagn Mol Pathol. 1 (4): 235–8. PMID 1342971.

- ↑ Franchi A, Calzolari A, Zampi G (1998). "Immunohistochemical detection of c-fos and c-jun expression in osseous and cartilaginous tumours of the skeleton". Virchows Arch. 432 (6): 515–9. PMID 9672192.

- ↑ Panagopoulos I, Mertens F, Isaksson M, Domanski HA, Brosjö O, Heim S; et al. (2002). "Molecular genetic characterization of the EWS/CHN and RBP56/CHN fusion genes in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma". Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 35 (4): 340–52. doi:10.1002/gcc.10127. PMID 12378528.

- ↑ Simon MA, Biermann JS (1993). "Biopsy of bone and soft-tissue lesions". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 75 (4): 616–21. PMID 8478391.

- ↑ Roitman PD, Farfalli GL, Ayerza MA, Múscolo DL, Milano FE, Aponte-Tinao LA (2017). "Is Needle Biopsy Clinically Useful in Preoperative Grading of Central Chondrosarcoma of the Pelvis and Long Bones?". Clin Orthop Relat Res. 475 (3): 808–814. doi:10.1007/s11999-016-4738-y. PMC 5289157. PMID 26883651.

- ↑ McCarthy EF, Hogendoorn PCW. Clear cell chondrosarcoma. In: World Health Organization classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone, 4th, Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F (Eds), IARC, Lyon 2013. p.273.

- ↑ Donati D, Yin JQ, Colangeli M, Colangeli S, Bella CD, Bacchini P; et al. (2008). "Clear cell chondrosarcoma of bone: long time follow-up of 18 cases". Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 128 (2): 137–42. doi:10.1007/s00402-007-0353-4. PMID 17522879.

- ↑ Itälä A, Leerapun T, Inwards C, Collins M, Scully SP (2005). "An institutional review of clear cell chondrosarcoma". Clin Orthop Relat Res. 440: 209–12. PMID 16239809.

- ↑ Nakashima Y, de Pinieux G, Ladanyi M. Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. In: WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone, 4th, Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn CDW, Mertens F (Eds), IARC, Lyon 2013. p.271.

- ↑ Frezza AM, Cesari M, Baumhoer D, Biau D, Bielack S, Campanacci DA; et al. (2015). "Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma: prognostic factors and outcome in 113 patients. A European Musculoskeletal Oncology Society study". Eur J Cancer. 51 (3): 374–81. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2014.11.007. PMID 25529371.

- ↑ Dantonello TM, Int-Veen C, Leuschner I, Schuck A, Furtwaengler R, Claviez A; et al. (2008). "Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of soft tissues and bone in children, adolescents, and young adults: experiences of the CWS and COSS study groups". Cancer. 112 (11): 2424–31. doi:10.1002/cncr.23457. PMID 18438777.

- ↑ Antonescu CR, Argani P, Erlandson RA, Healey JH, Ladanyi M, Huvos AG (1998). "Skeletal and extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: a comparative clinicopathologic, ultrastructural, and molecular study". Cancer. 83 (8): 1504–21. PMID 9781944.

- ↑ Aigner T, Oliveira AM, Nascimento AG (2004). "Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcomas do not show a chondrocytic phenotype". Mod Pathol. 17 (2): 214–21. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800036. PMID 14657948.

- ↑ Inwards C, Hogendoorn PCW. Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma In: WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone, 4th, Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F (Eds), IARC, Lyon 2013. p.269.

- ↑ Ryzewicz M, Manaster BJ, Naar E, Lindeque B (2007). "Low-grade cartilage tumors: diagnosis and treatment". Orthopedics. 30 (1): 35–46, quiz 47-8. PMID 17260660.

- ↑ Mirra JM, Gold R, Downs J, Eckardt JJ (1985). "A new histologic approach to the differentiation of enchondroma and chondrosarcoma of the bones. A clinicopathologic analysis of 51 cases". Clin Orthop Relat Res (201): 214–37. PMID 4064409.