Abdominal aortic aneurysm pathophysiology

|

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Microchapters |

|

Differentiating Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm from other Diseases |

|---|

|

Diagnosis |

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Abdominal aortic aneurysm pathophysiology On the Web |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Abdominal aortic aneurysm pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Abdominal aortic aneurysm pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2] Ramyar Ghandriz MD[3]

Overview

The underlying pathophysiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm involves genetic influences, smoking, hypertension, hemodynamic influences and underlying atherosclerosis. In rare instances infection, arteritis, and connective tissue disorders may play a role.

Pathophysiology

Pathology

- The most striking histopathological changes of aneurysmatic aorta are seen in tunica media and intima. [1]

- Changes indicated include an accumulation of lipids in foam cells( a kind of macrophage), extracellular free cholesterol crystals, calcifications, ulcerations, ruptures of the layers, and thrombosis.[2]

- There is an adventitial inflammatory infiltrate.

- The degradation of tunica media in proteolytic manners,is the basic process of abdominal aortic aneurysm initial phase. [3]

- Matrix metalloproteinases role in Abdominal aortic aneurysm has been shown by some researchers.[4]

- This leads to elimination of elastin from the media, rendering the aortic wall more susceptible to the influence of the blood pressure.

- Inflammation is another condition which plays a role in abdominal aortic aneurysm development.[5]

- The aortic wall has a specific arrangement of structural proteins that give it both strength and elasticity.

- The composition of the extracellular matrix protein in the media may change with age or in response to other conditions, therefore resulting in subsequent destruction of the elastic lamella, rendering the aorta less able to withstand the force of systolic pressure.

- The infra-renal aorta is more prone to develop aneurysms than other segments for the following reasons:[6]

- It is the segment that must expand the most during systole and contract the most during diastole.

- It has a thinner wall, and has fewer vasa vasora than the thoracic aorta.

- It is more prone to atherosclerosis, a proposed nidus for aneurysmal dilatation.

- Patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) also have atherosclerosis in the aorta and other arteries, suggesting that aneurysmal disease may be part of a larger spectrum of vascular disease, and that atherosclerosis actually promotes AAA formation.

- In atherosclerotic AAA, inflammatory cells infiltrate into the vessel wall and may secrete specific matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).[7]

- The different types of MMPs play diverse roles via complex interactions that eventually lead to degradation of the structural media proteins, and subsequently to aneurysmal dilatation.

- There are significantly fewer smooth muscle cells in human AAA tissues than in normal or atherosclerotic nonaneurysmal aortic tissue.

- This decrease in smooth muscle cells in suspected to be secondary to apoptosis, therefore suggesting a role for focal cell apoptosis in the pathogenesis of AAA.

Genetics

- There is likely a genetic component to the development of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. A familial pattern of inheritance is most notable in males.[8]

- It has been postulated that a variant of alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency may play a small role.

- It has also been postulated that there is a pattern of X-linked mutation, which would explain the lower incidence in heterozygous females.

Associated Conditions

- Smoking appears to be a critical environmental influence on the development of an abdominal aortic aneurysm.[9]

Hemodynamic Influences

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm is a focal degenerative process with a predilection for the infrarenal aorta.

- More than 90 % of abdominal aortic aneurysms occur in the infrarenal location.

- The higher incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the infrarenal region may be due to differences between the infrarenal and the thoracic aorta with respect to histologic and mechanical characteristics. [10]

- The diameter progressively decreases from the root to the bifurcation, and the wall of the abdominal aorta also contains a smaller proportion of elastin.

- The mechanical tension in the abdominal aortic wall is therefore higher than in the thoracic aortic wall.

- The elasticity and distensibility also decline with age, which can result in gradual dilatation of the segment.

- Higher intraluminal pressure in patients with arterial hypertension markedly contributes to the progression of the pathological process.[11]

Atherosclerosis

- Although abdominal aortic aneurysms are frequently involved with atherosclerosis, the exact role of atherosclerosis in the pathophysiology of abdominal aortic aneurysms remains unclear at this time.

Other

Other causes of the development of abdominal aortic aneurysm include:

- Arteritis

- Connective tissue disorders (e.g. Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome)

- Cystic medial necrosis

- Infection

- Trauma

Associated Diseases

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are associated with a high prevalence of systemic atherosclerosis:

- 23%-86% have coronary artery disease

- 3%-20% have cerebrovascular disease

- 12%-42% have peripheral arterial disease

Gross Pathology

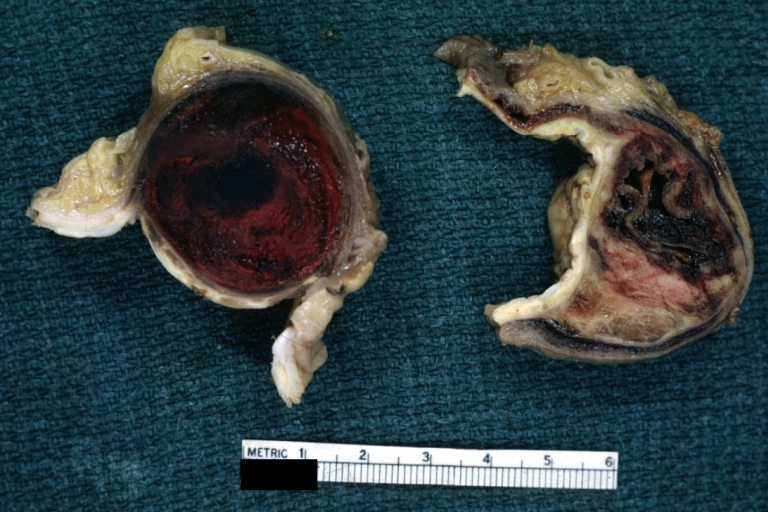

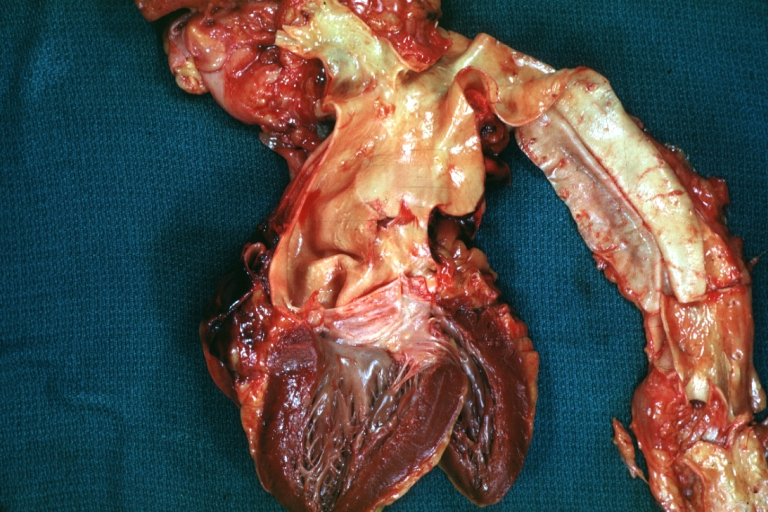

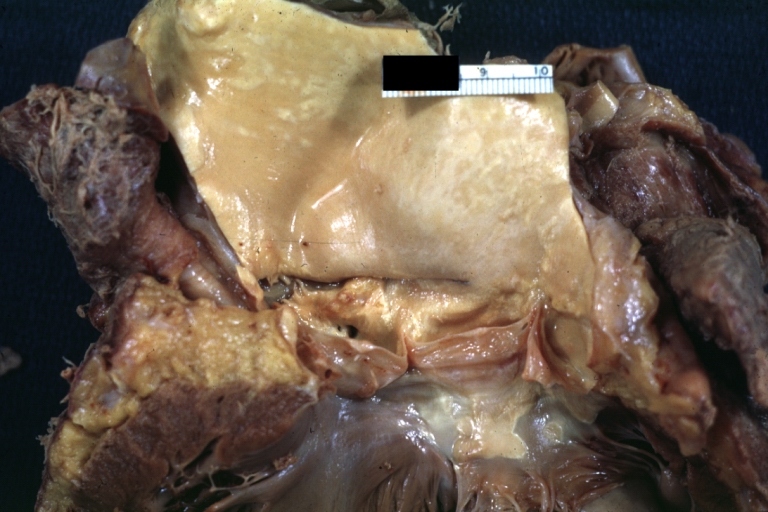

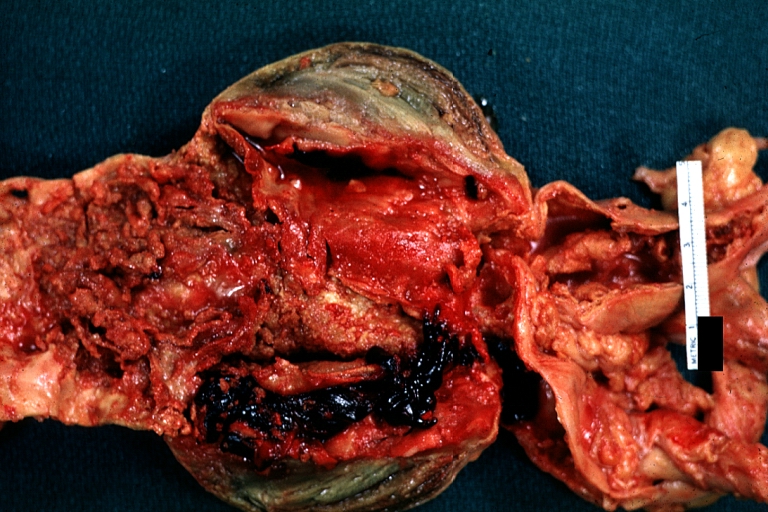

-

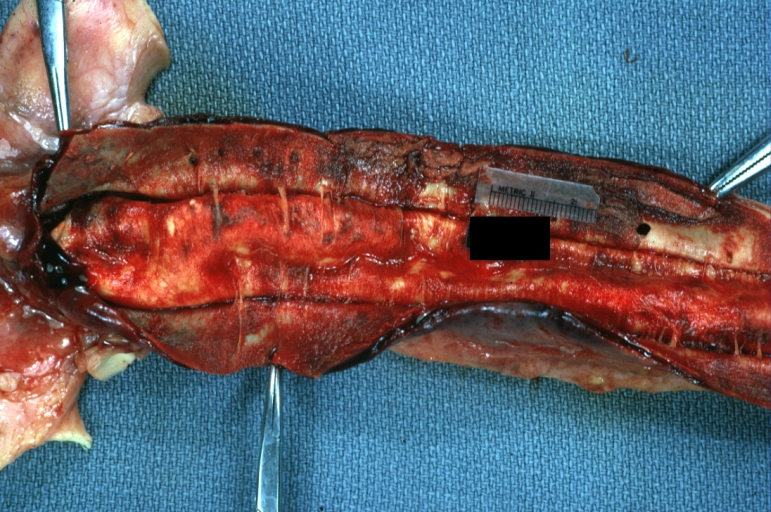

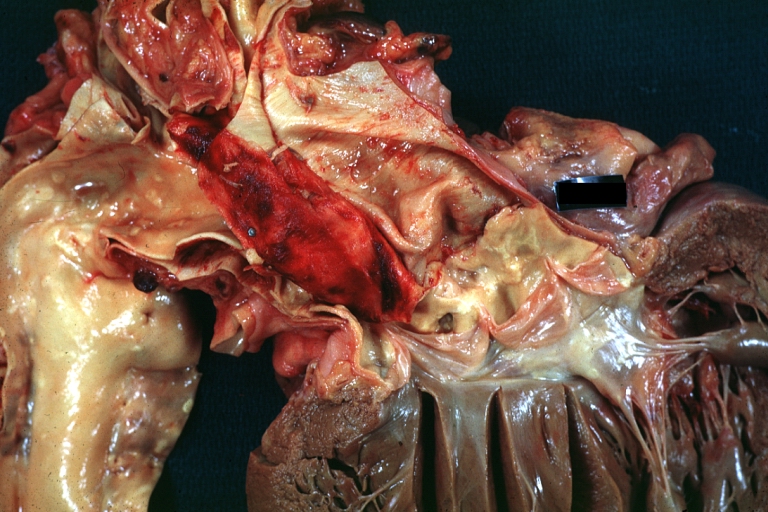

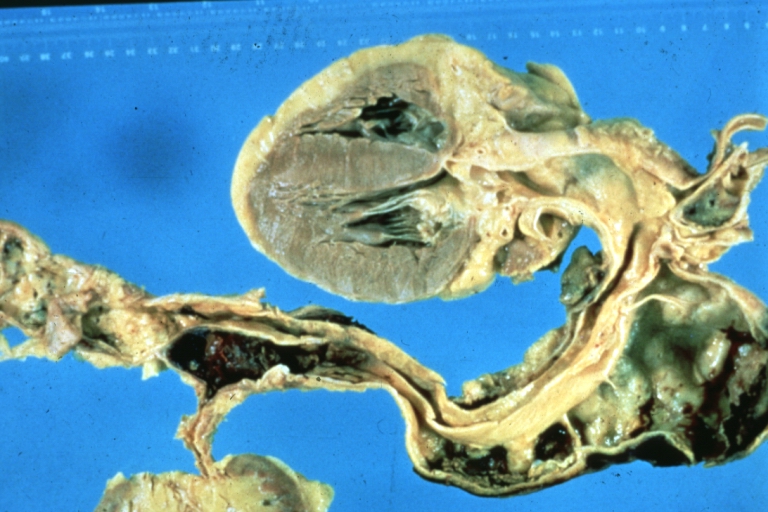

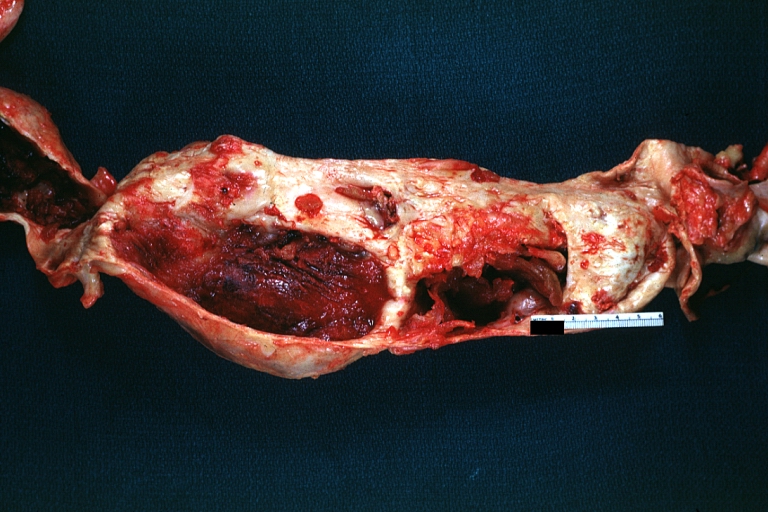

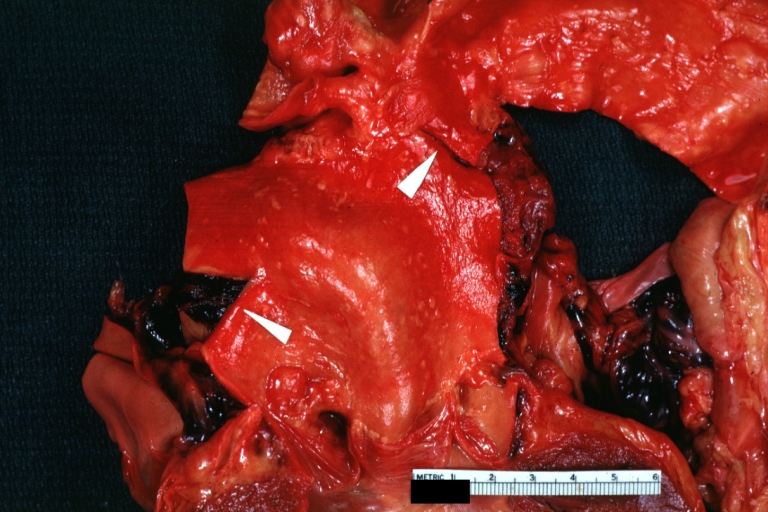

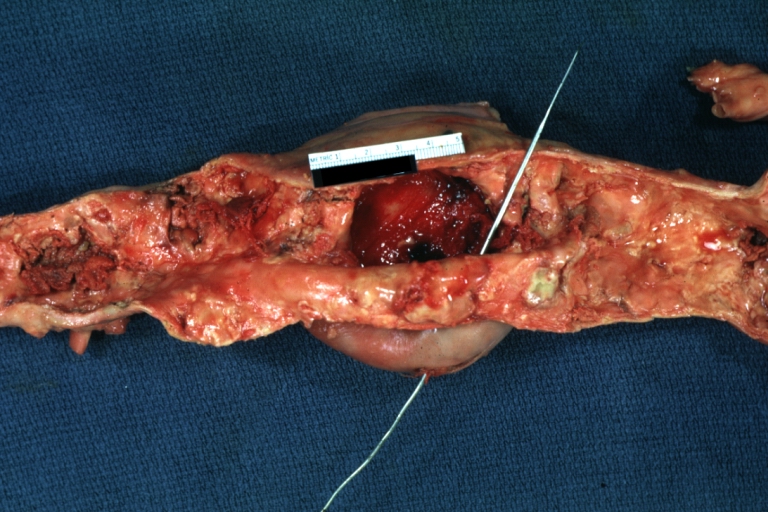

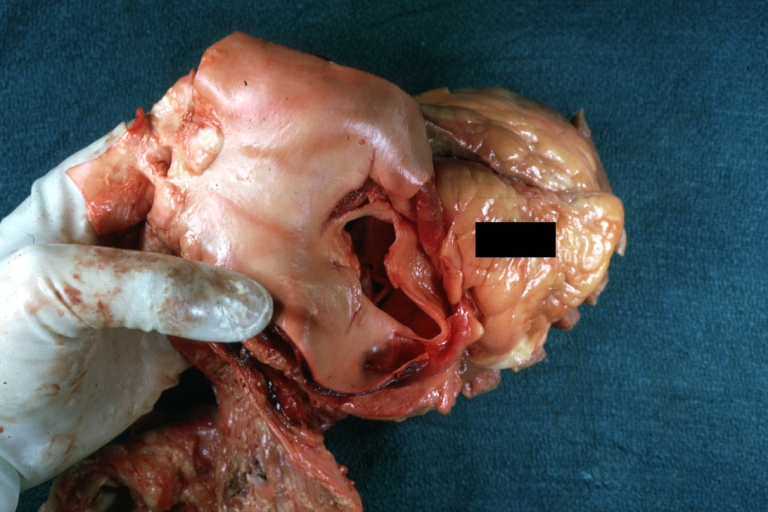

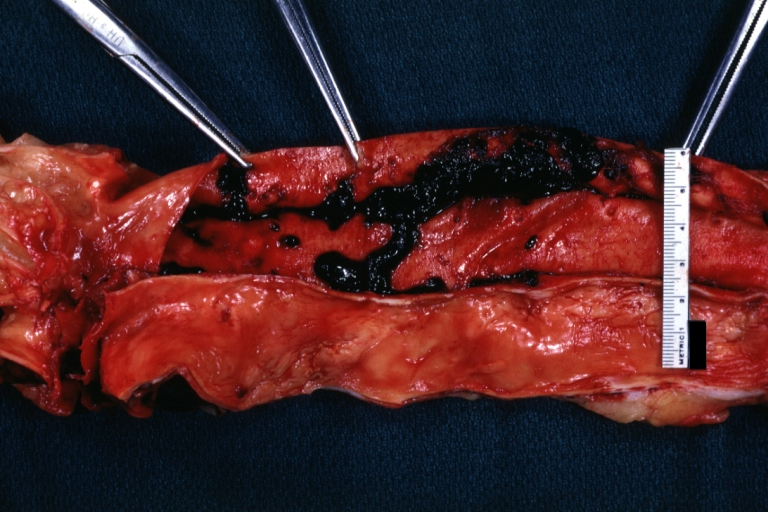

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross very good example dissected channel has been opened

-

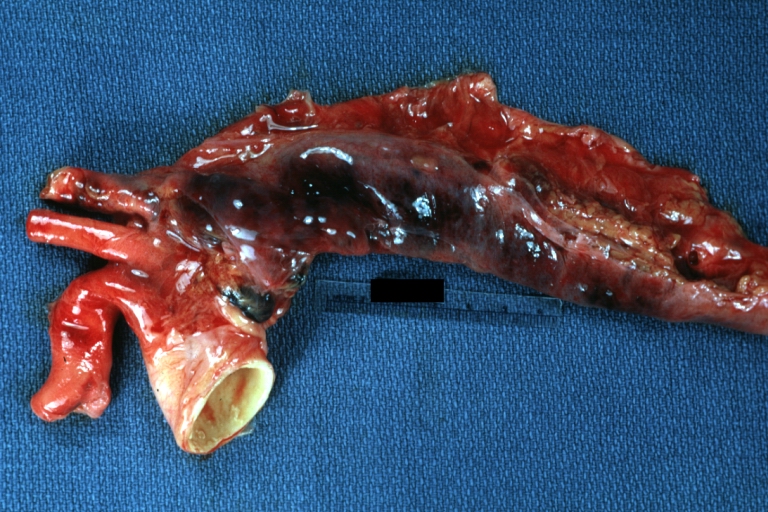

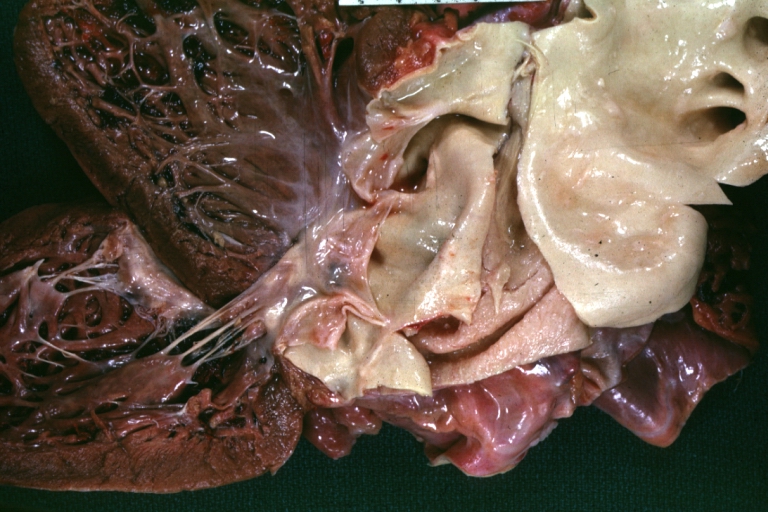

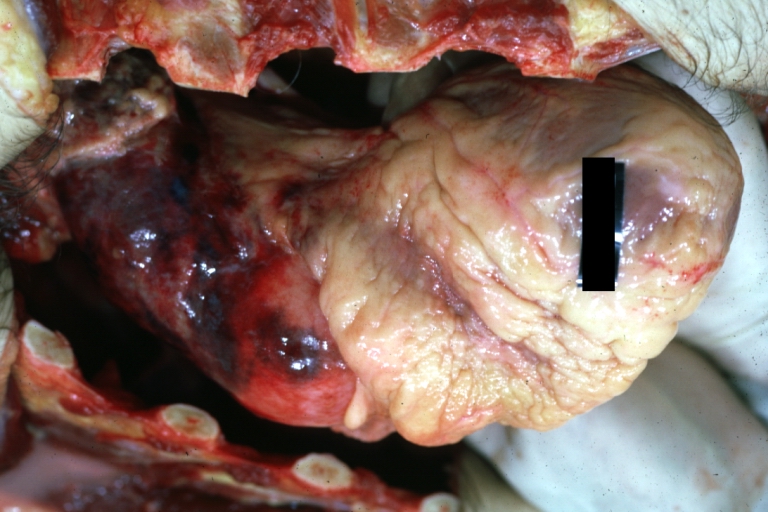

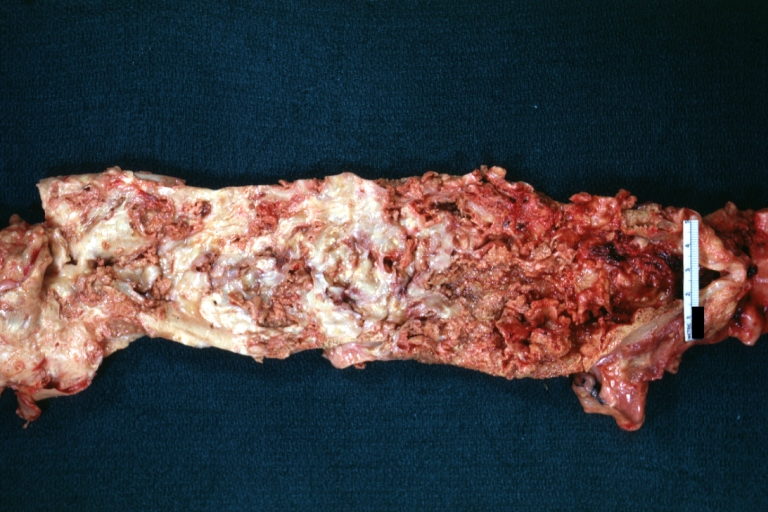

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross external view good appearance from adventitia

-

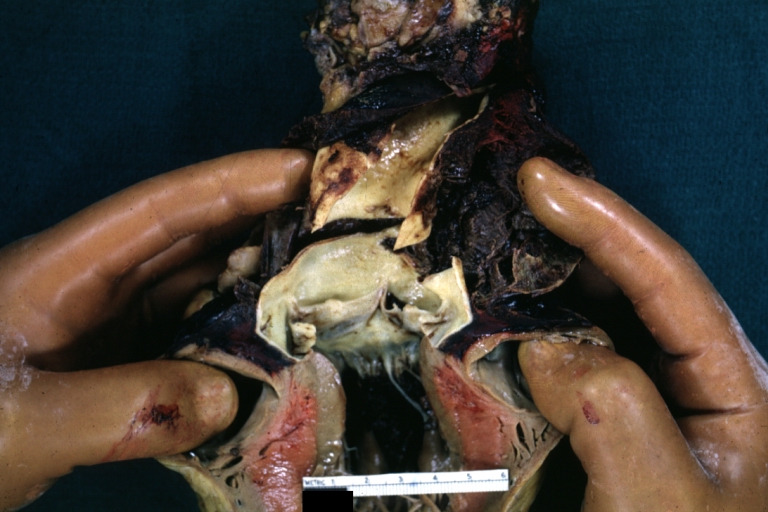

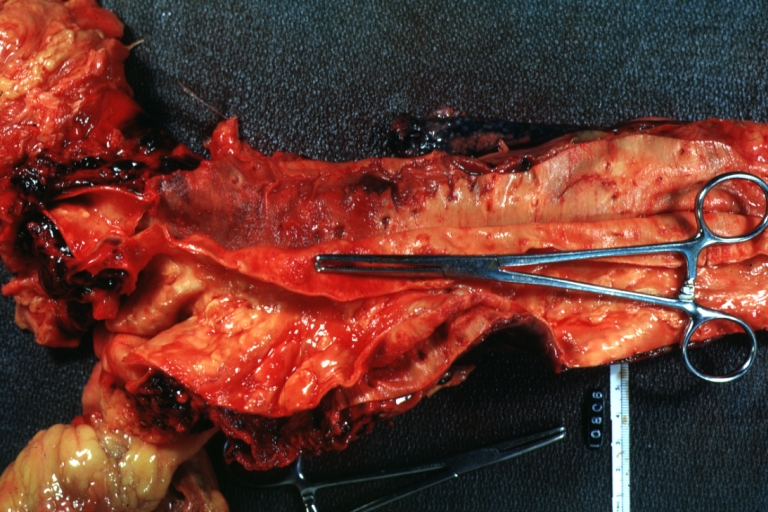

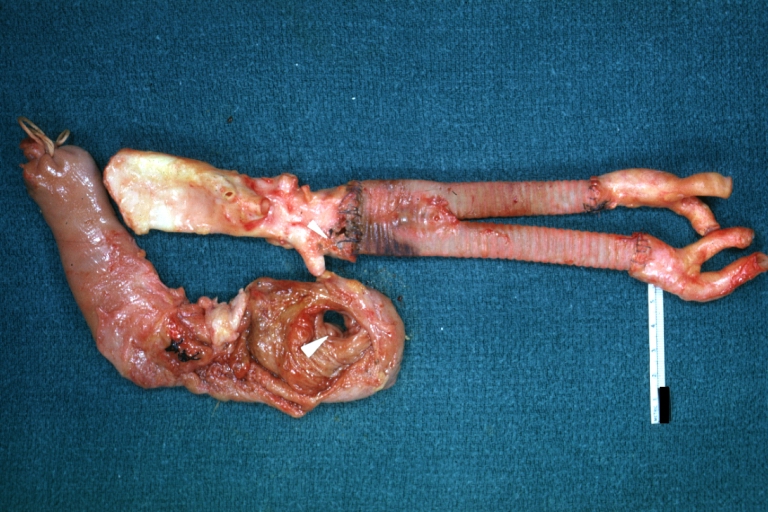

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross opened false channel

-

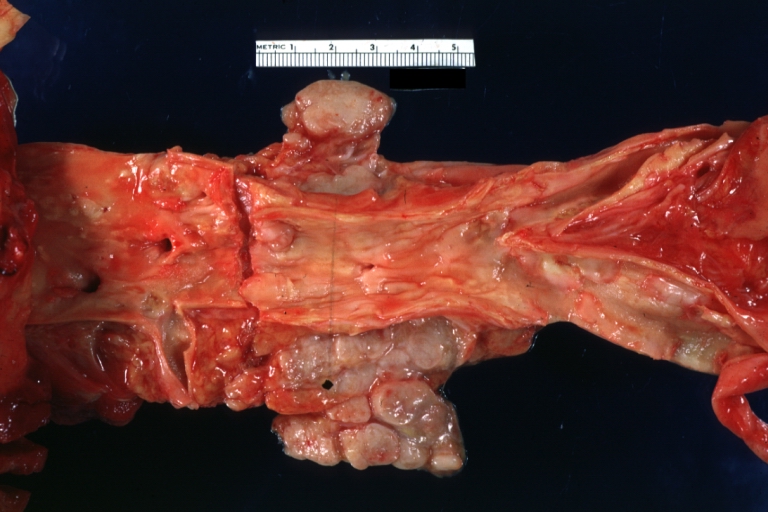

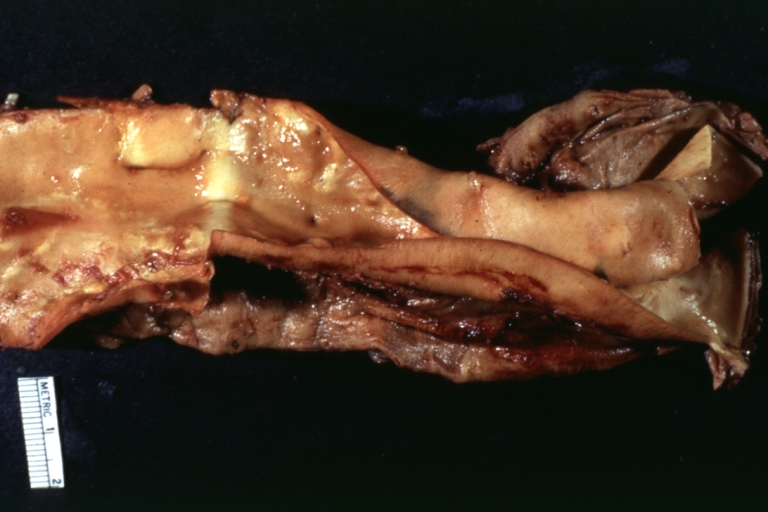

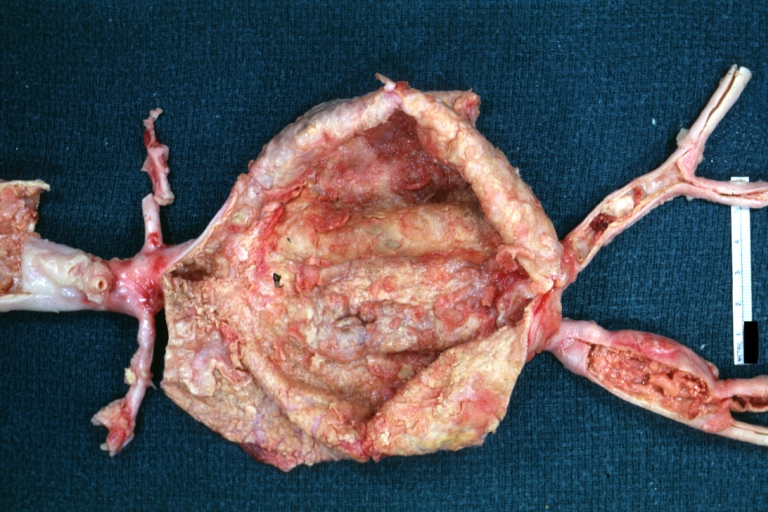

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross good example dissection beginning at third portion aortic arch

-

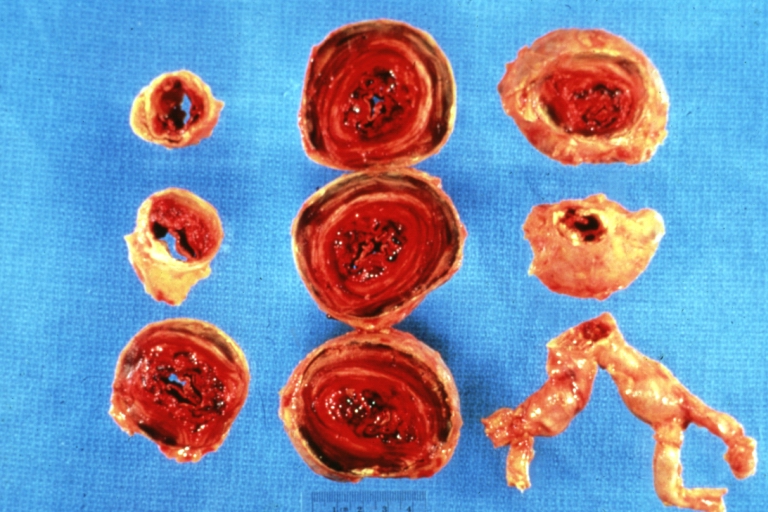

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross cross sections showing thrombus in false lumen true lumen has been opened longitudinally

-

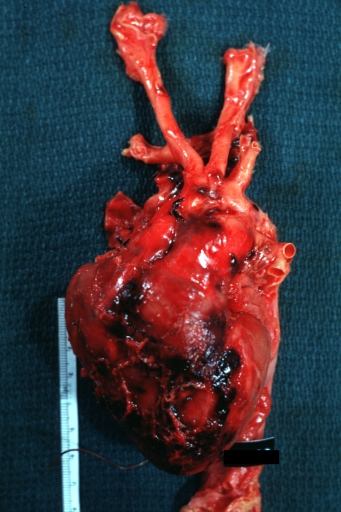

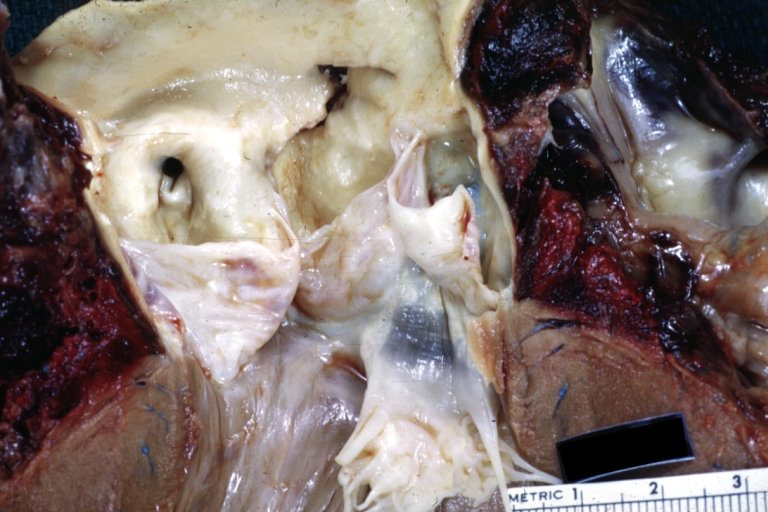

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross shows origin just above aortic valve false channel shown in descending thoracic aorta (very good example)

-

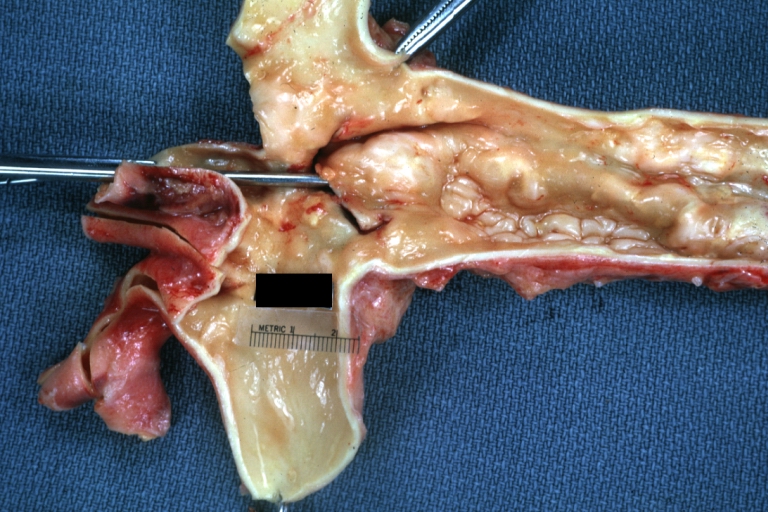

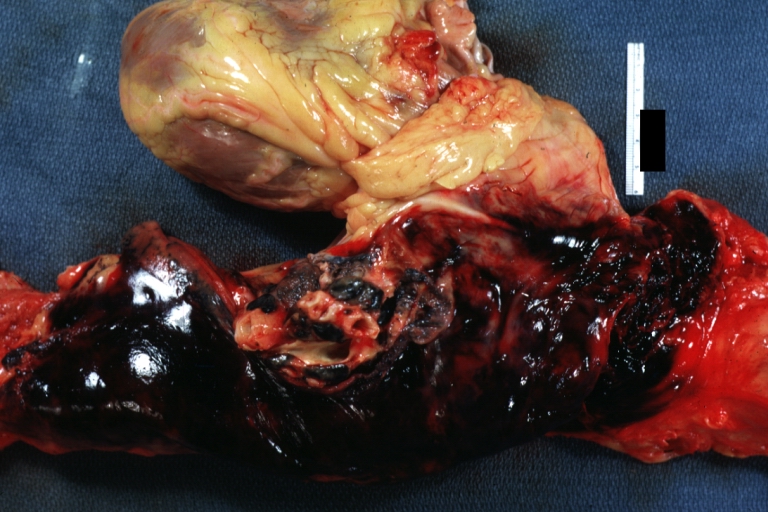

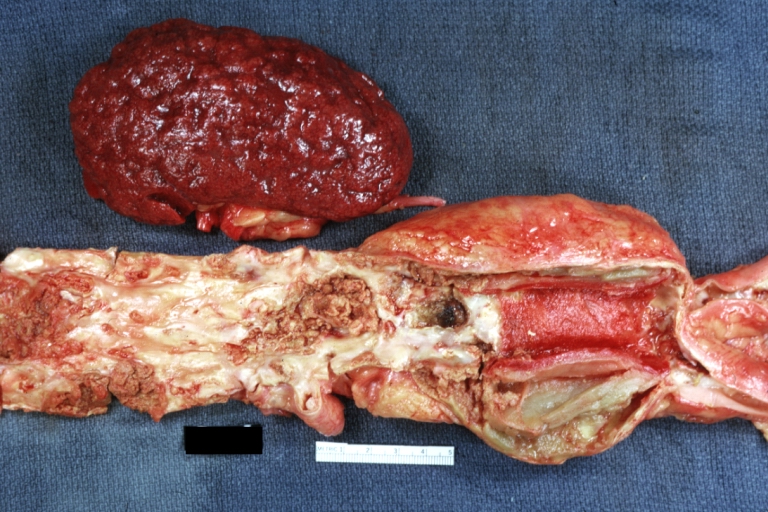

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm: Gross, a good example of typical abdominal aorta aneurysm with mural thrombus

-

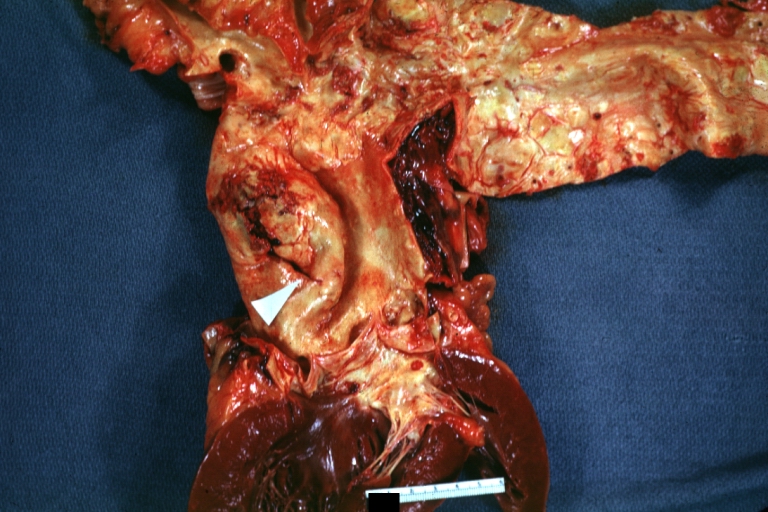

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, a very good example of dissection beginning just above aortic ring

-

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm: Gross, (rather) good example of abdominal aortic aneurysm

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, an excellent example, starting just above the aortic valve with reflection of aorta to show the dissection tract and some thrombus

-

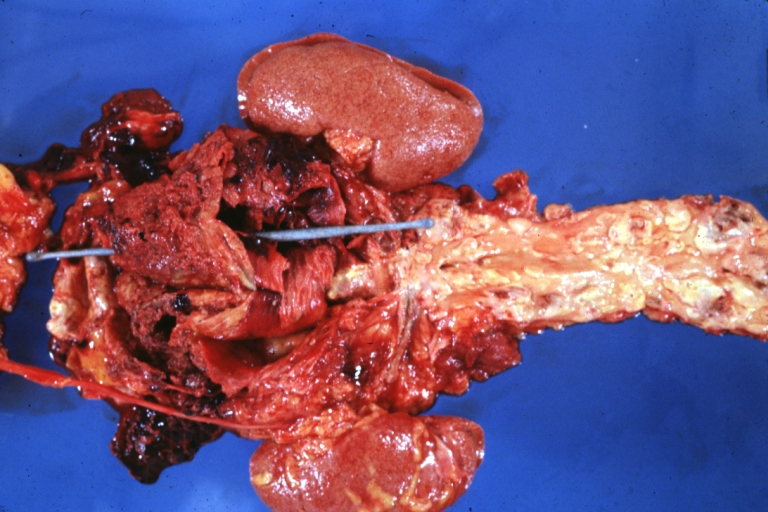

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross shows dilated aorta with extensive atherosclerosis dissection is seen, a small abdominal aorta atherosclerotic aneurysm is present good for association of dilation with dissection

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross arrow points to start of dissection in first portion aortic arch good but not the best example shows dilation

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, very good to show start of dissection above aortic valve and blood in false channel

-

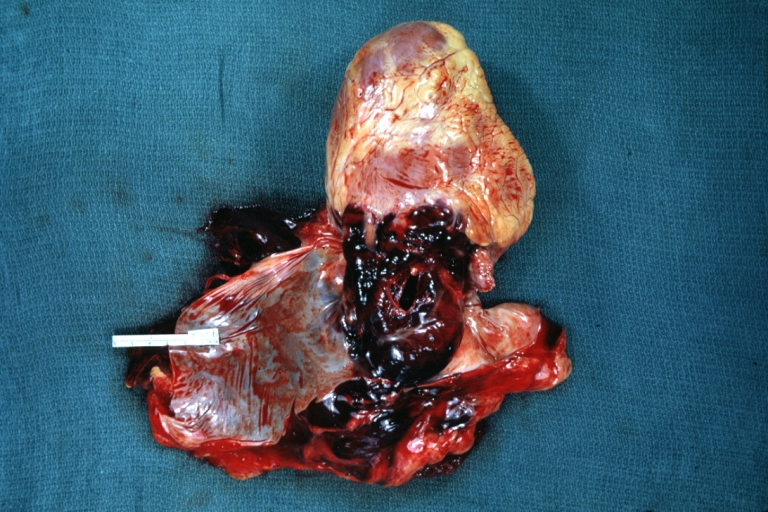

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, heart with root of aorta to show hemorrhage into pericardium (a very good example)

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, of heart and aorta with dissection and large false channel (a good example)

-

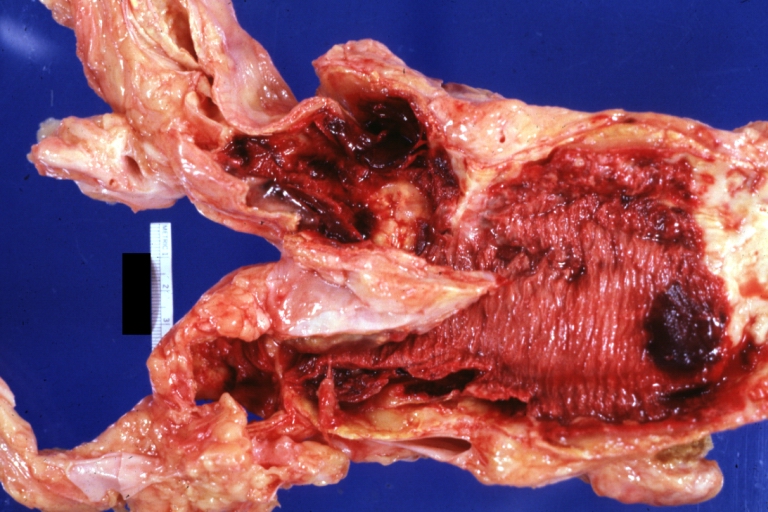

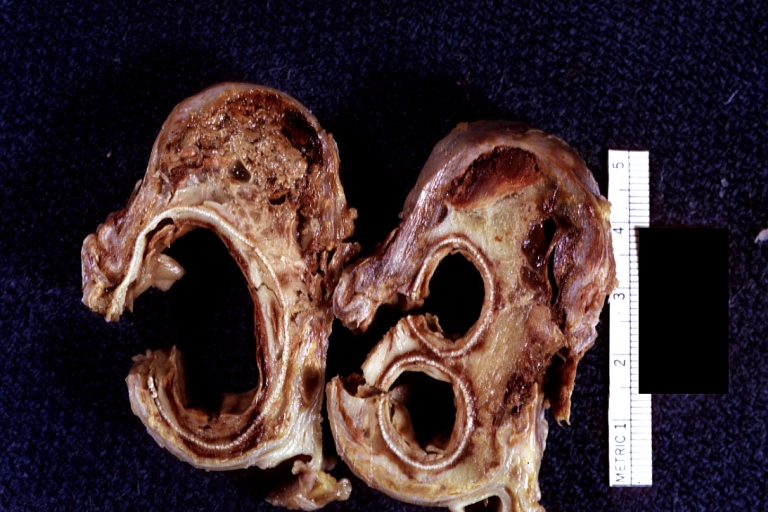

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross cross section of aorta with two channels (a good example)

-

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm: Gross, a nice view of cross section of abdominal aorta aneurysm

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross good example of typical angular tear above aortic valve

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross good example angular tear above aortic valve

-

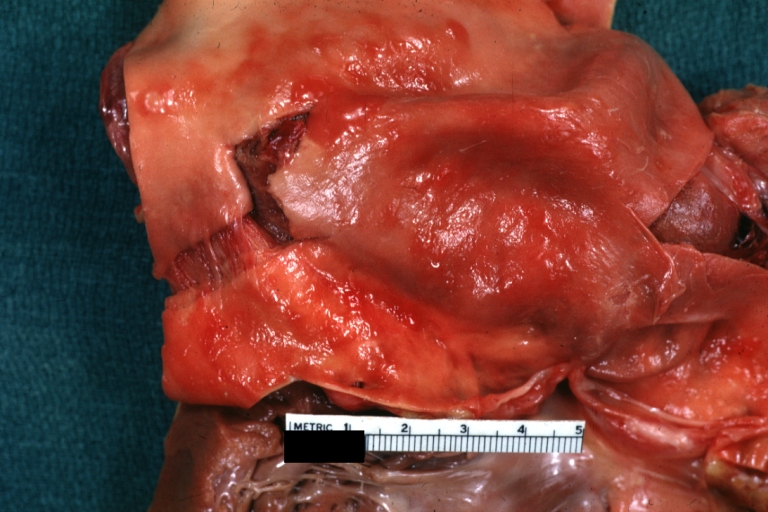

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm: Gross, external natural color very good example of an atherosclerotic thoracic aorta aneurysm with focal rupture

-

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm: Gross, excellent color, opened thoracic segment of aorta with two saccular atherosclerotic ruptured aneurysms

-

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm: Gross, an excellent example, natural color, external view of typical thoracic aortic aneurysms

-

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm: Gross unopened lesion natural color

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross dissection first portion of arch fixed specimen (a good example)

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, rather well shown dissection in first portion of the aortic arch

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, rather well shown dissection in first portion of the aortic arch

-

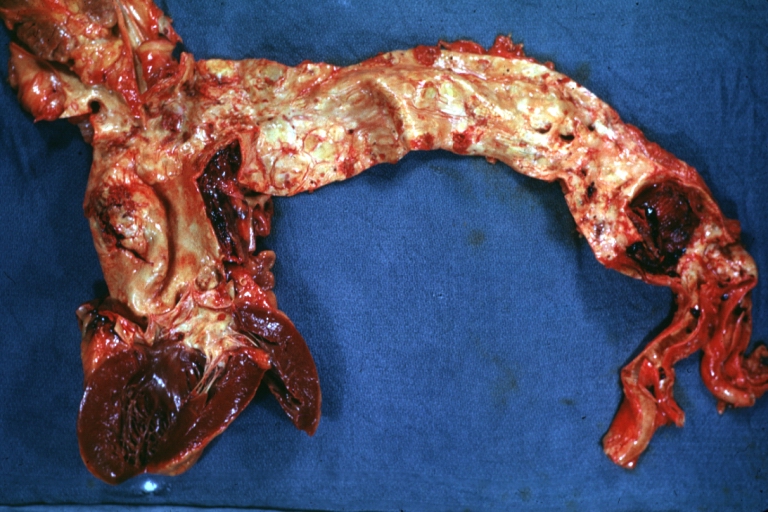

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, an excellent example of type I lesion

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, external view, an excellent example

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, Type I shows false channel

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, opened to show false channel (good example)

-

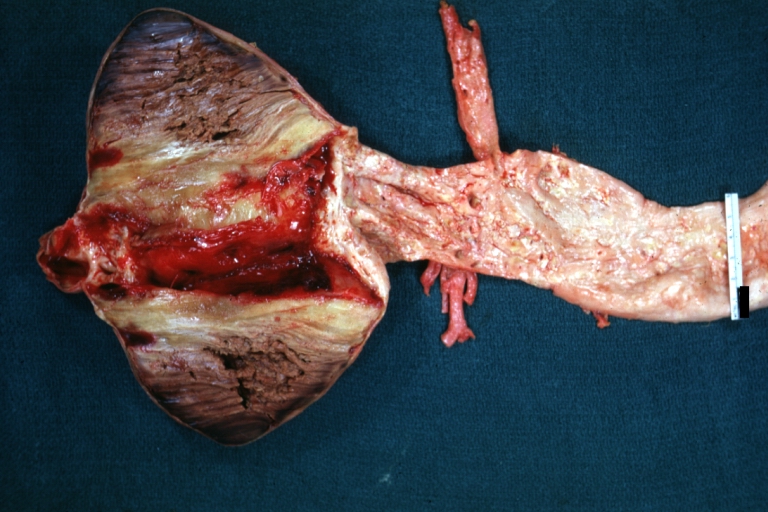

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm: Gross, very good example of ruptured thoracic segment

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, coagulum of blood in false channel

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, aortic valve area dissection (well shown, typical lesion)

-

Abdominal Aneurysm Ruptured: Gross (good example) opened kidneys in marked place, atherosclerosis in lower thoracic aorta

-

Abdominal Aneurysm: Gross, (very good example) opened lesion with mural thrombus

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, large tear in first portion of aortic arch, annuloaortic ectasis

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, external view of heart and first portion of aortic arch, annuloaortic ectasia, hemorrhage beneath adventitia is evidence of dissection

-

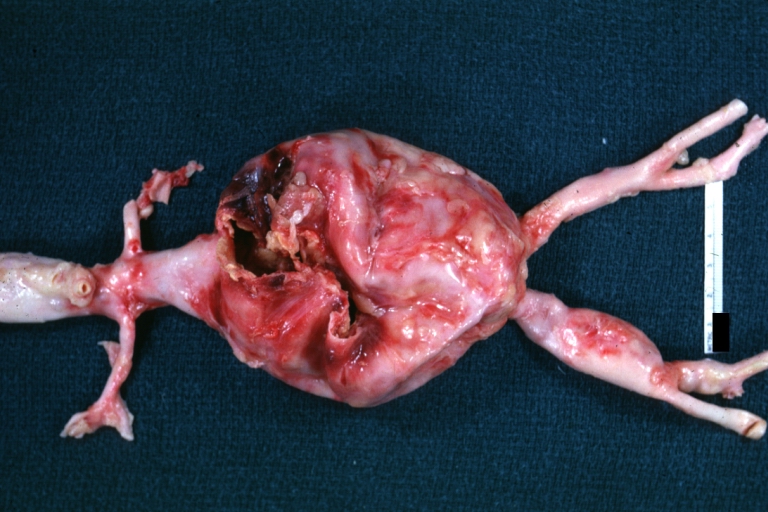

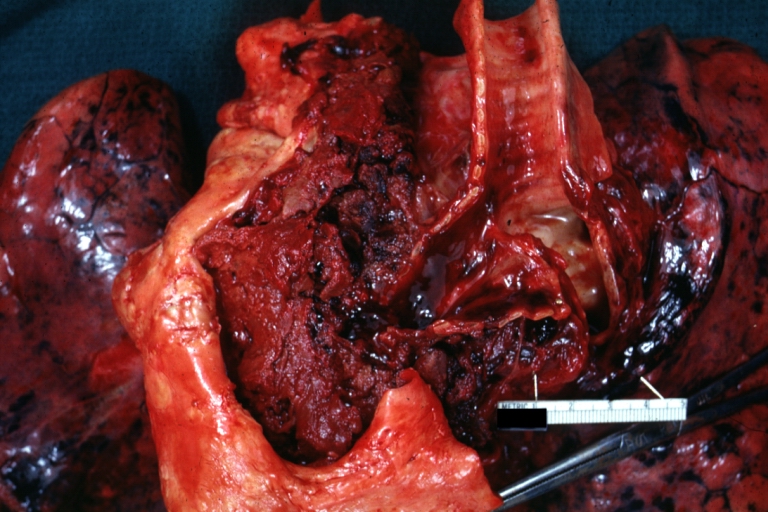

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm Infected: Gross, infected abdominal aneurysm at superior suture line with rupture into duodenum

-

Atherosclerotic Aneurysm: Gross, cross sections of repaired aneurysm showing Dacron graft and old mural thrombus. A nice example of fibrin layer in graft

-

Ruptured Syphilitic Aneurysm

-

Dissecting Aneurysm in a patient with Marfan's syndrome

-

Traumatic Aneurysm

-

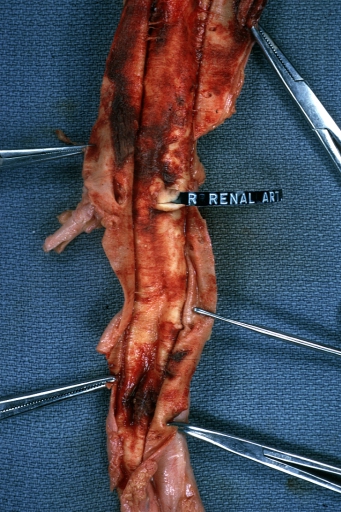

Kidney: Arteriosclerosis: Gross aorta with well shown renal artery containing large plaque and kidney with multiple cortical scars and atrophy also abdominal aorta aneurysm with mural thrombus (excellent example for renovascular hypertension)

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross, fixed tissue, descending thoracic segment dissection opened to show the false channel. The true surface is also visible

-

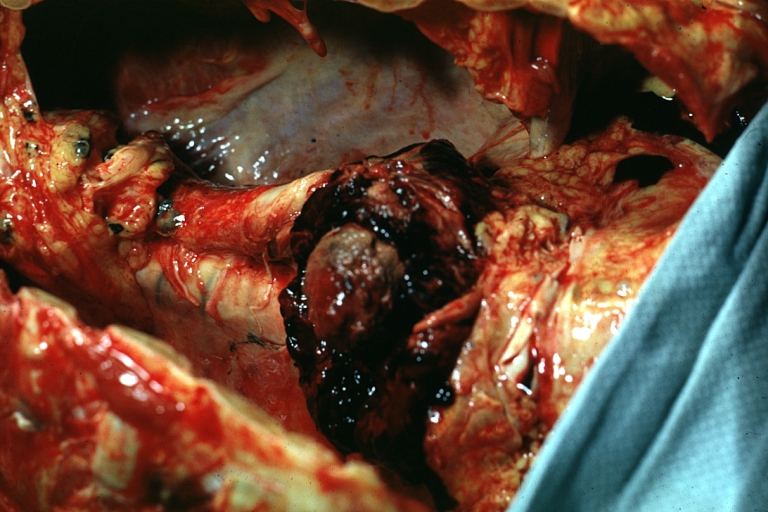

Aneurysm: Gross, ruptured thoracic aorta aneurysm, in situ lower thoracic portion (probably due to atherosclerosis)

-

Abdominal Aneurysm Graft Repair: Gross, natural color, close-up view, an excellent example of Dacron graft that has been in place for years with pseudointima and atherosclerosis

-

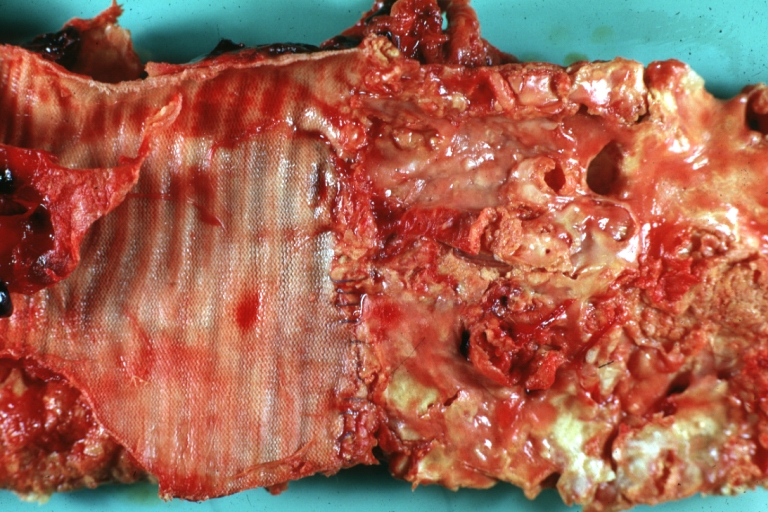

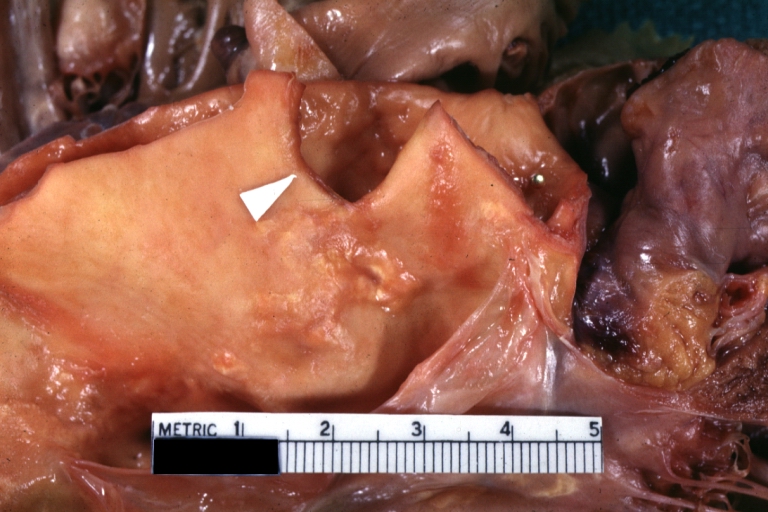

Dacron Graft: Gross, close-up Dacron graft to repair aneurysm. Aorta completely covered with a calcified and ulcerated plaque with small mural thrombi (an excellent depiction of proximal suture line)

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross natural color descending aorta opened into false channel

-

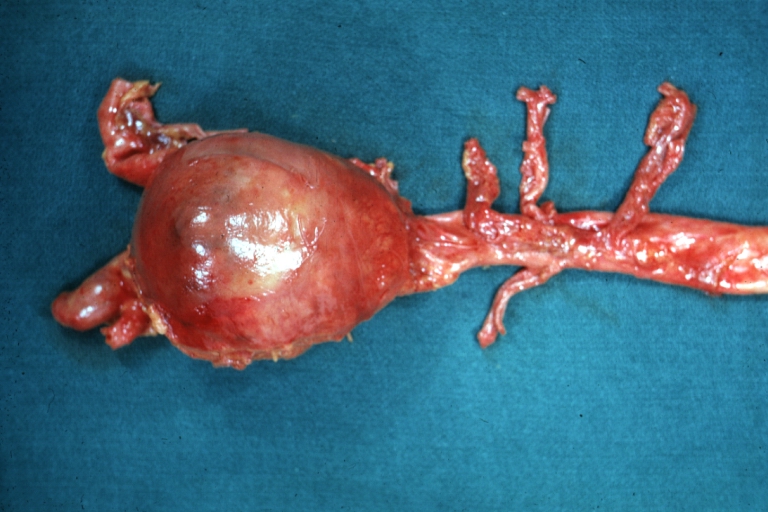

Abdominal Aneurysm: Gross, natural color, unopened specimen with about a six centimeter aneurysm between renals and bifurcation (a very good example of opened aneurysm)

-

Abdominal Aneurysm: Gross, natural color, an opened aneurysm showing quite well laminated thrombus

-

Atherosclerosis with Mural Thrombi: Gross, natural color, a nice photo of descending thoracic aorta with extensive ulcerated plaques and mural thrombi in distal portion. The case also has an abdominal aneurysm

-

Pseudoaneurysm Ruptured Into Duodenum: Gross natural color aorta and duodenum with arrow pointing to rupture point of aortobifemoral bypass pseudoaneurysm rupture and another in duodenum a very good demonstration of this very well known complication of aortic prostheses

-

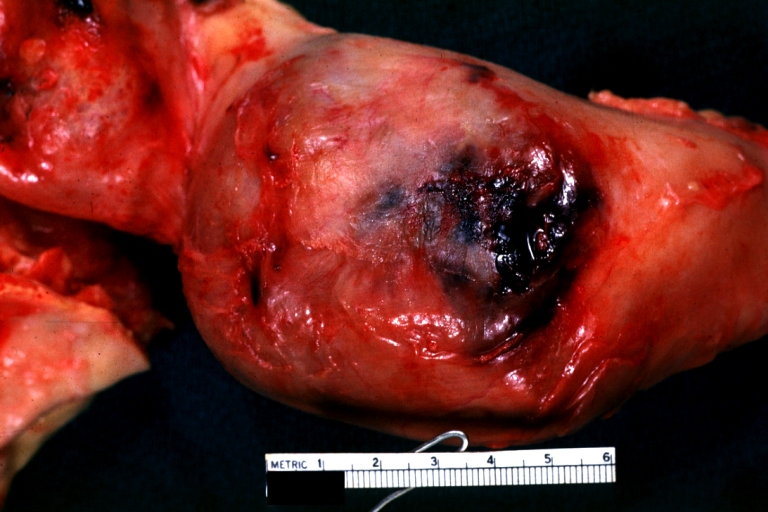

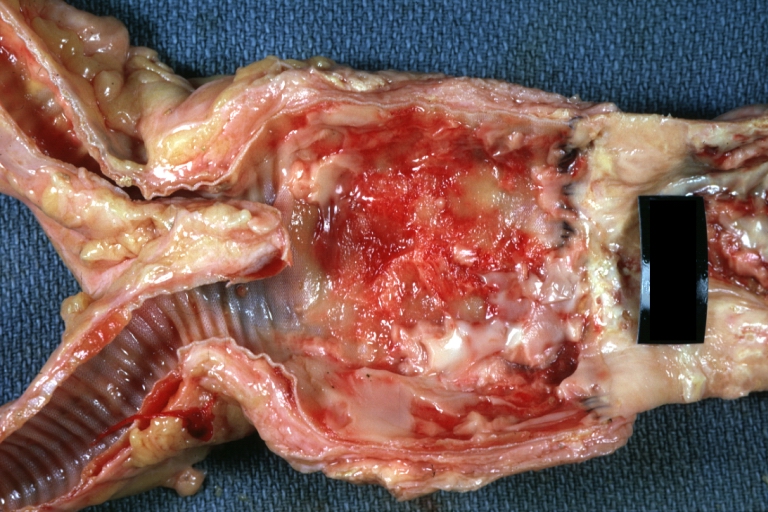

Abdominal Aneurysm: Gross, natural color, large aneurysm opened showing sessile calcified plaques with no mural thrombus. Lesion extends from renal arteries to the bifurcation (the same lesion seen externally with focus of rupture)

-

Abdominal Aneurysm Ruptured: Gross, natural color, external view with large area of apparent rupture. Aorta is opened to show this aneurysm)

-

Abdominal Aneurysm: Gross, natural color, unopened large and quite typical aneurysm extending from below renal arteries to bifurcation

-

Abdominal Aneurysm: Gross, natural color, opened aneurysm with well shown and typical laminated thrombus (external view)

-

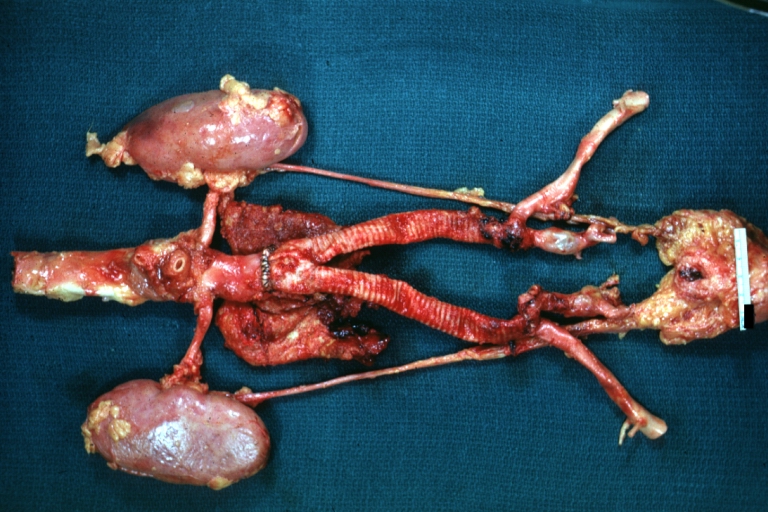

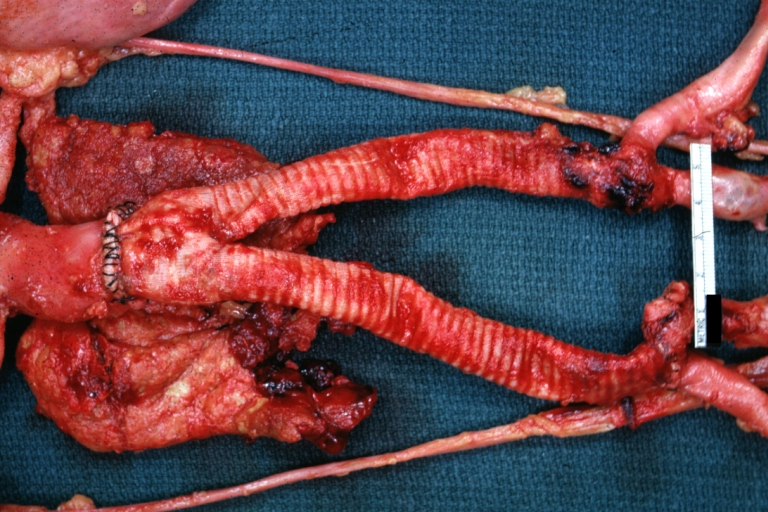

Aortobifemoral Prosthesis: Gross, natural color, nice dissection showing Dacron prosthesis replacing abdominal segment of aorta with portion of atherosclerotic aneurysm with renal arteries and kidneys

-

Aortobifemoral Prosthesis: Gross natural color close-up view of nicely dissected prosthesis extending from below renals to common iliac arteries portion of atherosclerotic aneurysm behind prosthesis

-

Dissecting Aneurysm: Gross natural color close-up view of aortic valve and proximal aortic arch with ruptured intima rather good illustration of this lesion

-

Syphilitic Aneurysm: Gross natural color rather a close-up view and outstanding photo of aneurysm ruptured into the left main stem bronchus

-

Syphilitic Aneurysm: Gross natural color typical tree barking in aorta aneurysm opening is seen in which is a thrombus aneurysm ruptured into left main stem bronchus (shown very well)

-

Dissecting Aneurysm Chronic: Gross natural color first portion of aortic arch with intimal rent well shown with healed margins and view into false channel that shows a surface looking like atherosclerosis which is known to develop in a chronic dissection

-

Dissecting Aneurysm Chronic: Gross, natural color, closer view of the previous one (a very good example)

References

- ↑ Jain D, Dietz HC, Oswald GL, Maleszewski JJ, Halushka MK (2011). "Causes and histopathology of ascending aortic disease in children and young adults". Cardiovasc Pathol. 20 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.carpath.2009.09.008. PMC 3046386. PMID 19926309.

- ↑ Grebe, Alena; Latz, Eicke (2013). "Cholesterol Crystals and Inflammation". Current Rheumatology Reports. 15 (3). doi:10.1007/s11926-012-0313-z. ISSN 1523-3774.

- ↑ Yetkin, Ertan; Ozturk, Selcuk (2018). "Dilating Vascular Diseases: Pathophysiology and Clinical Aspects". International Journal of Vascular Medicine. 2018: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2018/9024278. ISSN 2090-2824.

- ↑ Maguire, Eithne M.; Pearce, Stuart W. A.; Xiao, Rui; Oo, Aung Y.; Xiao, Qingzhong (2019). "Matrix Metalloproteinase in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Aortic Dissection". Pharmaceuticals. 12 (3): 118. doi:10.3390/ph12030118. ISSN 1424-8247.

- ↑ Li, Hanrong; Bai, Shuling; Ao, Qiang; Wang, Xiaohong; Tian, Xiaohong; Li, Xiang; Tong, Hao; Hou, Weijian; Fan, Jun (2018). "Modulation of Immune-Inflammatory Responses in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Emerging Molecular Targets". Journal of Immunology Research. 2018: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2018/7213760. ISSN 2314-8861.

- ↑ Aggarwal S, Qamar A, Sharma V, Sharma A (2011). "Abdominal aortic aneurysm: A comprehensive review". Exp Clin Cardiol. 16 (1): 11–5. PMC 3076160. PMID 21523201.

- ↑ Ramella M, Boccafoschi F, Bellofatto K, Follenzi A, Fusaro L, Boldorini R; et al. (2017). "Endothelial MMP-9 drives the inflammatory response in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)". Am J Transl Res. 9 (12): 5485–5495. PMC 5752898. PMID 29312500.

- ↑ Clifton, MA: Familial abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br. J. Surg., 64, 1977, p. 765-766

- ↑ Norman, Paul E.; Curci, John A. (2013). "Understanding the Effects of Tobacco Smoke on the Pathogenesis of Aortic Aneurysm". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 33 (7): 1473–1477. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300158. ISSN 1079-5642.

- ↑ Wang, Linda J.; Prabhakar, Anand M.; Kwolek, Christopher J. (2018). "Current status of the treatment of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms". Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy. 8 (S1): S191–S199. doi:10.21037/cdt.2017.10.01. ISSN 2223-3652.

- ↑ Fitridge R, Thompson M (2011). "Mechanisms of Vascular Disease: A Reference Book for Vascular Specialists". PMID 30485032.