|

|

| Line 59: |

Line 59: |

| == Diagnosis == | | == Diagnosis == |

|

| |

|

| [[Pericarditis history and symptoms| History and Symptoms]] | [[Pericarditis physical examination | Physical Examination]] | [[Pericarditis laboratory findings | Laboratory Findings]] | | [[Pericarditis history and symptoms| History and Symptoms]] | [[Pericarditis physical examination | Physical Examination]] | [[Pericarditis laboratory findings | Laboratory Findings]] |

|

| |

|

| | ==[[Pericarditis treatment| Treatment]]== |

|

| |

|

| == Physical Examination == | | ==[[Pericarditis Pharmacotherapies | Pharmacotherapies]]== |

| | |

| === Appearance of the Patient with Pericarditis ===

| |

| # [[Fever]] less than 39° C or 102.2° F

| |

| #* Patients who are elderly may not exhibit fever; however, they may be [[hypothermic]] especially those with [[renal failure]].

| |

| # [[Chills]] (suppurative pericarditis and idiopathic (viral) pericarditis)

| |

| # [[Weakness]]

| |

| # [[Depression]]

| |

| # [[Anxiety]]

| |

| # [[Pallor]] (may also indicate [[tuberculosis]], [[uremia]], [[neoplasia]], and rheumatic carditis)

| |

| | |

| === Heart ===

| |

| '''Ausculatory Phenomena:'''

| |

| # Pericardial Rub(s): Usually heard with acute pericarditis, sometimes with subacute and chronic. This is the major indicator of pericarditis.

| |

| #* endopericardial rub: inflamed, scarred or tumor-invaded serosal surfaces

| |

| #* exopericardial rub: after sclerotherapy of effusions, between parietal pericardium and pleura or chest wall (occasionally)

| |

| #* endo-exopericardial rub: both of the above

| |

| #* pleuropericardial rub: [[pleuritis]] as a result of pleural or both pleural and pericardial both

| |

| # Abnormal Heart Sounds:

| |

| #* Sounds are dampened as a result of fluid insullation

| |

| #* Hemodynamic changes diminish S<sub>1</sub> and S<sub>2</sub>

| |

| # Clicks: Ventricular volume shrinks disproportionately and psuedoprolapse/true prolapse of mitral and/or tricuspid valvular structures result in clicks.

| |

| # Murmurs: are epiphenomena and may be present if there is coinciding heart disease, narrowing of a valve, aorta, pulmonary artery or another area of the heart.

| |

| === Lungs ===

| |

| | |

| [[Rales]] are frequent examination findings, occasionally [[pleural fluid]] may present.

| |

| | |

| === Extremities ===

| |

| #May be poorly perfused in the setting of tamponade

| |

| #Edema may be present in the setting of pericardial constriction

| |

| | |

| == Laboratory Findings ==

| |

| | |

| === Electrolyte and Biomarker Studies ===

| |

| | |

| '''''Inflammatory markers'''''. A [[Complete Blood Count|CBC]] may show an elevated white count and a serum [[C-reactive protein]] may be elevated.

| |

| | |

| '''''Molecular markers'''''. Acute pericarditis is associated with a modest increase in serum [[creatine kinase]] MB (CK-MB)<!--

| |

| --><ref name="spodick">{{cite journal | author= Spodick DH | title= Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice | journal= JAMA | year=2003 | pages=1150–3 | volume=289 | issue=9 | pmid=12622586 | doi= 10.1001/jama.289.9.1150}}</ref><!--

| |

| --><ref name="karja">{{cite journal | author= Karjalainen J, Heikkila J | title= "Acute pericarditis": myocardial enzyme release as evidence for myocarditis | journal= Am Heart J| year=1986| pages=546–52 | volume=111 | issue=3 | pmid=3953365 | doi= 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90062-1}}</ref> and cardiac [[troponin]] I (cTnI)<!--

| |

| --><ref name="bonnefoy">{{cite journal | author= Bonnefoy E, Godon P, Kirkorian G, Fatemi M, Chevalier P, Touboul P | title= Serum cardiac troponin I and ST-segment elevation in patients with acute pericarditis | journal= Eur Heart J| year=2000| pages=832–6 | volume=21 | issue=10 | pmid=10781355 | doi= 10.1053/euhj.1999.1907}}</ref><!--

| |

| --><ref name="imazio">{{cite journal | author= Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E, Belli R, Ghisio A, Bobbio M, Trinchero R | title= Cardiac troponin I in acute pericarditis | journal= J Am Coll Cardiol| year=2003| pages=2144–8 | volume=42 | issue=12 | pmid=14680742 | doi= 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.02.001}}</ref>, both of which are also markers for myocardial injury. Therefore, it is imperative to also rule out [[acute myocardial infarction]] in the face of these biomarkers. The elevation of these substances is related to inflammation of the myocardium. Also, ST elevation on [[EKG]] (see below) is more common in those patients with a cTnI > 1.5 µg/L<!--

| |

| --><ref name="imazio">{{cite journal | author= Imazio M, Demichelis B, Cecchi E, Belli R, Ghisio A, Bobbio M, Trinchero R | title= Cardiac troponin I in acute pericarditis | journal= J Am Coll Cardiol| year=2003| pages=2144–8 | volume=42 | issue=12 | pmid=14680742 | doi= 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.02.001}}</ref>. [[Coronary angiography]] in those patients should indicated normal vascular perfusion. The elevation of these biomarkers are typically transient and should return to normal within a week. Persistence may indicated myopericarditis. As a summary:

| |

| | |

| * [[ESR]]: mild to marked elevation

| |

| * [[CRP]]: mild to marked elevation

| |

| * [[CK-MB]]: depends on the extent of myocardial involvement

| |

| * [[LDH]]: depends on the extent of myocardial involvement

| |

| * [[troponin I]]: depends on the extent of myocardial involvement

| |

| * serum myoglobin: normal (but not always, usually rises with increased ST segment deviation

| |

| * gallium-67 scanning: helps ID "inflammatory and leukemic infiltrations"

| |

| | |

| === Electrocardiogram ===

| |

| | |

| '''[[Electrocardiography|EKG Abnormalities]]:''' Increase in scar tissue, fluid and fibrin can reduce voltage, quasi-specific ST-T waves can present. The [[EKG]] abnormalities vary depending on the stage/severity of the pericarditis. Below are the stages/types of pericarditis:<!--

| |

| --><ref name="troughton">{{cite journal | author= Troughton RW, Asher CR, Klein AL | title= Pericarditis | journal= Lancet| year=2004| pages=717–27 | volume=363 | issue=9410 | pmid=15001332 | doi= 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15648-1}}</ref><!--

| |

| --><ref name="spodick">{{cite journal | author= Spodick DH | title= Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice | journal= JAMA | year=2003 | pages=1150–3 | volume=289 | issue=9 | pmid=12622586 | doi= 10.1001/jama.289.9.1150}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Stadia pericarditis.png|thumb|left|600px|Several stages of pericarditis. Stage I: ST elevation in all leads; PTa depression (depression between the end of the P wave and the beginning of the QRS complex). Stage II: Pseudonormalization (transition). Stage III: inverted T waves. Stage IV: normalization. (Courtesy of ECGpedia)]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| #''Acute Pericarditis'' (see also [[Electrocardiography#The PR Interval]] and [[Electrocardiography#The EKG of Cardiac Transplantation]]): this variation of the disease in conjunction with myocarditis can lead to ST-T anomalies that are characteristic of the acute stages of pericarditis.

| |

| #*''Stage 1'': Stage 1 of acute pericarditis, in and of itself, presents as "early repolarization" and acute infarction. It shows signs of anterior and inferior ST elevation on the [[EKG]]. There are usually no deviations in the QRS complex. This stage is largely characteristic of acute pericarditis when almost all of the leads are effected. Leads I, II, avL, avF, and V<sub>3</sub>-V<sub>6</sub>.

| |

| #*''Stage 2'': During the early phase of this stage, ST segments should become baseline again; whereas, PR segments may have deviated. During the latter phase of stage 2, the ST segments that were previously elvated usually flatten and invert.

| |

| #*''Stage 3'': Virtually all of the leads in stage 3 exhibit T wave inversion. Acute pericarditis cannot be diagnosed on an [[ECG]] of a stage 3 patient because its presentation is the same as myocardial injury and frank myocarditis.

| |

| #*''Stage 4'': This stage presents itself on the [[EKG]] as a return to a prepericarditis state. Stage 4 does not always occur and in its absence, there can be residual T wave inversions that may be permanent, generalized or focal.

| |

| #''Rate and Rhythm'': Rapid heart rates are typical in patients with pericarditis, but in patients with uremic pericarditis slower rates are observed. Heart rhythms appear normal unless there is another complication such as cardiac disease, the presence of myocardial/pericardial tumor, or a metabolic disorder.

| |

| #''[[Pericardial Effusion]]'' (see also [[Electrocardiography#Amplitude]]): These can present differently on the [[EKG]] depending on whether they are chronic vs large effusions. The former typically leads to low amplitude [[EKG]]s; whereas, the latter can show no voltage or various [[Electrocardiography|ECG abnormalities]]. ST-T wave abnormalities can be caused by superficial myocarditis or because of the accumulated fluid, they may be caused by the compression of the myocardium or [[ischemia]]. The primary cause of ST segment variation during pericardial effusions is usually the rapid accumulation of fluid. Large effusions can lead to the reduction of P wave voltage. [[Pleural effusions]] can cause a decrease in voltage, which occurs mainly on the left. Also, [[cirrhosis]] and [[congestive heart failure]] ([[CHF]]), which similarily involve the accumulation of fluid in the body, can decrease voltage in the absence of any pericardial disease.

| |

| #''[[Cardiac tamponade]]'' (see also [[Cardiac tamponade#Electrocardiogram]]): Generally has little [[EKG]] effect; however, in the acute form, tamponade may present on the [[EKG]] as any one of the stages of acute pericarditis.

| |

| #''Electrical Alternation'': This occurs more often in cases of tamponade than in those of pericarditis (2:1). There is alternation of the QRS complex on the spatial axis. Alternation of the T wave, P wave, and PR segement are difficult to see and are uncommon. The removal of even a small amount of fluid can end alternation.

| |

| #''Early Repolarization'': This finding can be misleading and may look like pericarditis, when in fact it is not. A strong indication of pericarditis is "if the J point is more than 25% the height of the T wave apex."

| |

| #''Constrictive Pericarditis'': Cases of constrictive pericarditis have nonspecific [[EKG]] abnormalities. Common abnormalities include: a slightly "low voltage QRS" segment combined with "flattened to inverted T waves", during stage 3 of acute/subacute constriction the T wave inversions remain or worsen and "P waves can be wide and bifid." It is not uncommon for patients to have normal [[EKG]]s. Many patients may only exhibit "nonspecific T wave abnormality." Other influencial factors that may effect the [[EKG]] in constrictive pericarditis are: [[fluid retention]], [[ascites]], and [[pleural effusions]]. The two most common [[arrhythmias]] that occur are [[atrial fibrillation]] and [[atrial flutter]].

| |

| #*''QRS Abnormality'': characteristic RV hypertrophy QRS abnormalities may develop as a result of disproportionate constriction or postpericardiectomy scarring. Also, "focal atrophy, scarring or inflamation" may cause "abnormal Q waves."

| |

| #**''Chronic Constrictive Pericarditis'': low volatage and myocardial atrophy, "frontal QRS axis" is usually vertical (becomes more vertical with increasing chronicity),

| |

| #**''Acute/Subacute Pericarditis'': QRS axis appears as normal

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Acute-pericarditis.jpg|left|350px|thumb|Acute Pericarditis]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Ptadepressieecg.png|left|350px|thumb|Acute Pericarditis]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:12leadpericarditis.png|left|350px|thumb|Acute Pericarditis]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Peri022.jpg|left|350px|thumb|Acute Pericarditis]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Ptadepressie.png|left|350px|thumb|An example of clear PTa depression]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Alternans.jpg|left|350px|thumb|Pericardial Effusion]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| ====Summary of EKG findings====

| |

| | |

| Typical lead involvement: I, II, aVL, aVF, and V3-V6.

| |

| | |

| The ST segment is always depressed in aVR, frequently in V1, and occasionally in V2. Occasionally, stage IV does not occur and there are permanent T wave inversions and flattenings.

| |

| | |

| If EKG is first recorded in stage III, pericarditis cannot be differentiated by EKG from diffuse myocardial injury, "biventricular strain," or myocarditis.

| |

| | |

| EKG in early repolarization is very similar to stage I. Unlike stage I, this EKG does not acutely evolve and J point elevations are usually accompanied by a slur, oscillation, or notch at the end of the QRS just before and including the J point (best seen with tall R and T waves – large in early repolarisation pattern).

| |

| | |

| Pericarditis is likely if in lead V6 the J point is >25% of the height of the T wave apex (using the PR segment as a baseline).

| |

| | |

| === Chest X Ray ===

| |

| | |

| The heart will be enlarged on CXR in the setting of [[tamponade]] with a significant pericardial effusion.

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Mesothelial cyst of the pericardium.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Mesothelial cyst of the pericardium. Note the rounded mass in the right costophrenic angle (arrow).]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| === Cardiac MRI <small><ref>Higgins CB, De Roos A (2003) Cardiovascular MRI and MRA. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia</ref></small> ===

| |

| | |

| CMR provides good resolution for identifying many types of pericardial pathology. On T1-weighted spin echo imaging, the pericardium appears as a thin, low-signal band bordered by bright, high-signal bands corresponding to epicardial and pericardial fat. The pericardium on CMR appears black because of its low water content. With gadolinium, however, it may enhance in acute inflammation. Normal thickness of the pericardium on CMR is 2-4mm, although the thickness has been shown to be slightly greater than expected from pathological studies due to chemical shift caused by the fat overlying the pericardium.

| |

| | |

| ====Cardiac MRI in Constrictive pericarditis====

| |

| | |

| Because pericardial thickness is easily measured on CMR, it is considered the definitive approach for diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis; coronal and axial spin-echo CMR have been reported to have a sensitivity of 88%, specificity of 100%, and diagnostic accuracy of 93% in making this diagnosis. In addition, depending on the severity of the constrictive pericarditis, dilatation of the IVC, hepatic veins, and right atrium as well as a normal or compressed/elongated right ventricle can be seen. Differentiating between causes of pericardial thickening can be difficult, however; inflammatory etiologies usually lead to greater thickening than [[Category:]]fibrotic ones. Also, in chronic constriction the thickened pericardium displays a lower intensity than in acute pericarditis.

| |

| | |

| ====Cardiac MRI in pericardial effusions====

| |

| | |

| It is important to distinguish the thickness of the pericardium from any pericardial effusion, which commonly appears black on spin echo images but bright on gradient echo cines. Moderate-sized effusions are often associated with a pericardial space anterior to the right ventricle of size greater than 5mm. Cine images can detect cardiac tamponade by revealing diastolic collapse of right sided and sometimes left-sided cardiac chambers. Regarding the composition of pericardial effusions, transudates have low signal on T1-weighted images but high signal on T2-weighted and gradient echo images. Exudates display an intermediate signal on both types of sequences. Hemorrhagic effusions may show a wide range of signal intensity on spin-echo sequences that depends on the age of the effusion.

| |

| | |

| ====Cardiac MRI in other pericardial pathologies====

| |

| | |

| Other types of pericardial pathology detectable by CMR include pericardial cysts; metastasis and primary tumors of the pericardium; and intracardiac tumors such as myxomas, lipomas, and teratomas. The signal intensity of fluid within pericardial cysts increases progressively with echo time, leading to accurate detection. Pericardial calcification, on the other hand, is not well-detected by CMR. Calcium appears black on CMR and therefore may resemble a localized area of pericardial thickening; cardiac CT is preferred for visualizing pericardial calcification.

| |

| | |

| ===Computed Tomography (CT) <small><ref>Chotas HG, Dobbins JT, Ravin CE (1999) Principles of digital radiography with large-area, electronically readable detectors: a review of the basics. Radiology 210:595-599</ref> <ref>Ohnesorge BM, Becker CR, Flohr TG, Reiser MF (2001) Multislice CT in cardiac imaging. Springer-Verlag</ref> </small>===

| |

| | |

| '''Pericardial Effusion'''

| |

| | |

| Cross-sectional imaging by CT or MRI is very sensitive in the detection of generalized or loculated pericardial effusions. Some fluid in the pericardial sac contributes to the apparent thickness and should be considered normal. Commonly, free-flowing fluid accumulates first at the posterolateral aspect of the left ventricle, when the patient is imaged in the supine position.

| |

| | |

| Estimation of the amount of fluid is possible to a limited extent based on the overall thickness of the crescent of fluid. Compared to cardiac ultrasound, CT and MRI may be particularly helpful in detecting loculated effusions, owing to the wide field of view provided by these techniques. Hemorrhagic effusions can be differentiated from a transudate or an exudate based on signal characteristics (high signal on T1-weighted images) or density (high-density clot on CT). Pulsation artefacts may cause local areas of low signal in a hemorrhagic effusion. Effusions are often incidentally noted on CT scans obtained for other indications.

| |

| | |

| Pericardial thickening (thickness >4 mm) is difficult to differentiate from a small generalized effusion. Both entities will reveal a low signal/density line that is thicker than the normal pericardial thickness. In acute pericarditis, the pericardial lining can show intermediate signal intensity and may enhance after gadolinium administration.

| |

| | |

| [http://www.radswiki.net Images courtesy of RadsWiki]

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Pericard-effusion-01.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Chest x-ray: Pericardial effusion]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Pericard-effusion-02.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Chest x-ray: Pericardial effusion. The second day of admission]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Pericard-effusion-03.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Cardiac MSCT: Pericardial effusion]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| '''Constrictive Pericarditis'''

| |

| | |

| Pericardial thickening may result in constrictive pericarditis. In this entity, pericardial thickening will hamper cardiac function, with hemodynamic consequences. Many disease conditions can lead to constrictive pericarditis (infection, tumor, radiation, heart surgery, etc.).

| |

| | |

| The diagnostic features include thickened pericardium in conjunction with signs of impaired right ventricular function: dilatation of caval veins and hepatic veins, enlargement of the right atrium, and the right ventricle itself may be normal or even reduced (tubular, sigmoid) in size due to compression. Localized pericardial thickening may also cause functional impairment (localized constrictive pericarditis). Sometimes constriction may occur despite a normal appearance of the pericardium.

| |

| | |

| Pericardial calcifications are easily visualized by CT but may be difficult or impossible to appreciate on MRI.

| |

| | |

| '''Pericardial Tumor'''

| |

| | |

| A pericardial cyst is most commonly located at the right cardiophrenic angle. On T1, it appears either as a low signal or an intermediate signal due to high protein content, or with a characteristic light-bulb appearance on T2.

| |

| | |

| Unusual tumors may arise from the pericardium (mesothelioma, angiosarcoma, etc.). Malignant primary tumors have many overlapping imaging features and generally cannot be differentiated. The role of cross-sectional imaging is to establish a diagnosis and to define the extent of the lesion (invasion of cardiac structures, veins, pericardium, etc.). Sometimes lesions may have helpful signal characteristics to suggest a specific diagnosis, e.g., high-signal fat on T1 or low-density fat on CT in lipoma / liposarcoma.

| |

| | |

| Secondary tumors are much more common than primary tumors. Lung cancer may invade the mediastinal and cardiac structures directly or indirectly.

| |

| | |

| The most common secondary tumors affecting the heart are lung cancer, breast cancer, and lymphoma. Metastatic pericardial disease commonly presents as hemorrhagic effusion. Tumor nodules may enhance after intravenous gadolinium administration.

| |

| | |

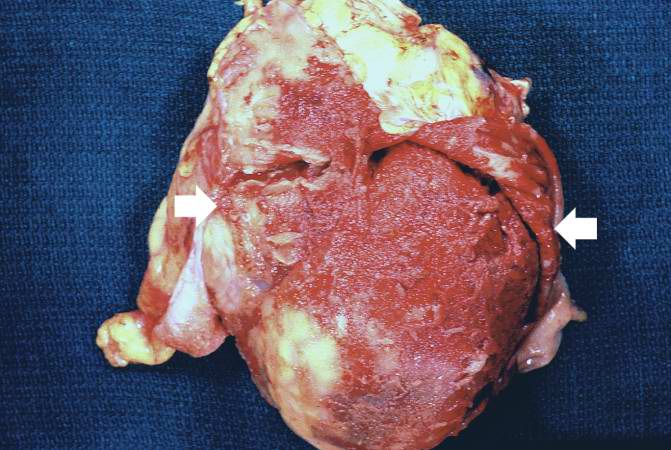

| '''Pericardial Metastases'''

| |

| | |

| [http://www.peir.net Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology]

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Pericardial metastasis 1.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Pericardial Metastases]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Pericardial metastasis 2.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Pericardial Metastases]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Pericardial metastasis 3.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Pericardial Metastases]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Pericardial metastasis 4.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Pericardial Metastases]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Pericardial metastasis 5.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Pericardial Metastases]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| [[Image:Pericardial metastasis 6.jpg|left|thumb|350px|Pericardial Metastases]]

| |

| <br clear="left"/>

| |

| | |

| === [[Echo in pericardial diseases: effusion, cardiac tamponade, constriction|Echocardiographic Findings]]===

| |

| | |

| ===Radioscopic Findings===

| |

| | |

| * Calcified pericardium in constructive pericarditis

| |

| | |

| <youtube v=blSXL5z02fY/>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <youtube v=LXWitpJQEGQ/>

| |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| ===Pathological Findings===

| |

| | |

| ====Gross Images====

| |

| | |

| [http://www.peir.net Images courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology]

| |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0001.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, an excellent example of bread and butter appearance. Uremia, chronic glomerulonephritis and sepsis.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0002.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, a good example (bread and butter appearance).

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0003.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0004.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example, close-up view of fibrin.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0005.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example, close-up view.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0006.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0007.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, external view of localized pericarditis over an acute infarction

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0008.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, intact heart, good example

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0009.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, good example, mild, with small amount of fibrin

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0010.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, close-up, an excellent example of color and detail

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0011.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, a good example

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0012.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, a good example, very mild case

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0013.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, an excellent example.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0014.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, a close-up view, an excellent illustration of fibrinous exudate.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0015.jpg|Pericarditis in [[uremia]]

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0016.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, fixed tissue (note to color changes), a close-up view of fibrin on epicardial surface of heart. A typical example.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0017.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, large right atrial thrombus and fibrinous pericarditis. Normal [[tricuspid valve]] with some aging changes (good example)

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0018.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0019.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, an excellent example

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0020.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, very close-up photo showing fibrinous exudate simulating frost (an excellent example)

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0021.jpg|Rheumatoid fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, a typical lesion in 22 years old white female due to juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0022.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, close-up view of minimal fibrinous exudate on epicardial surface due to terminal renal failure

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0023.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, anterior view of heart with mild fibrinous exudate over epicardium due to terminal renal failure

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0024.jpg|Tuberculous pericarditis: Gross, natural color, shaggy hemorrhagic exudate. This case is much more hemorrhagic than the typical tuberculous pericarditis.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0025.jpg|Heart transplant: Gross, natural color, external view of heart. Two months after transplantation with fibrinous pericarditis

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0026.jpg|Neoplastic pericarditis: Gross, natural color, shaggy pericarditis. Primer is adenocarcinoma of the lung.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0027.jpg|Heart: Septic pericarditis

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 001.jpg|Hemopericardium: Gross, an excellent in situ view

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 002.jpg|Hemopericardium: Gross, in situ, unopened pericardium (a very good example)

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 003.jpg|Hemopericardium: Gross, natural color, heart in situ with opened pericardium and filled with red blood clot (quite good example) dissecting aneurysm

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 004.jpg|Hemopericardium due to Needle Puncture: Gross, natural color, external view of heart covered by blood

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 005.jpg|Needle Puncture Mark in Epicardium: Gross, natural color, close-up of needle puncture marks tap resulted in hemopericardium

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 006.jpg|Hemopericardium: Hemopericardium caused by pericardiocentesis: Gross, natural color, close-up view of apex of the heart. Needle apparently entered the distal posterior descending artery.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 007.jpg|Hemopericardium: Hemopericardium caused by pericardiocentesis: Gross, natural color, view of apex of the heart. Needle apparently entered the distal posterior descending artery

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 008.jpg|Hemopericardium: Hemopericardium due to pericardiocentesis: Gross, fixed tissue, close-up view of slice through distal posterior descending artery showing periarterial hemorrhage

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 009.jpg|Hemopericardium: Liver: Gross, natural color, typical shock liver case of death due to hemopericardium secondary to pericardiocentesis

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 010.jpg|Hemopericardium in newborn: Gross, natural color, opened body with large collection blood in pericardial sac. Cause uncertain. A 26 week premature with hyaline membrane disease and DIC

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 011.jpg|Hemopericardium: Myocardial Infarction and Ventricular Rupture

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 012.jpg|Hemopericardium: Infarct rupture after 7 days of chest pain onset.

| |

| Image:Hemopericardium 013.jpg|Hemopericardium in dissecting aneurysm: Gross, heart with root of aorta to show hemorrhage into pericardium (very good example)

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

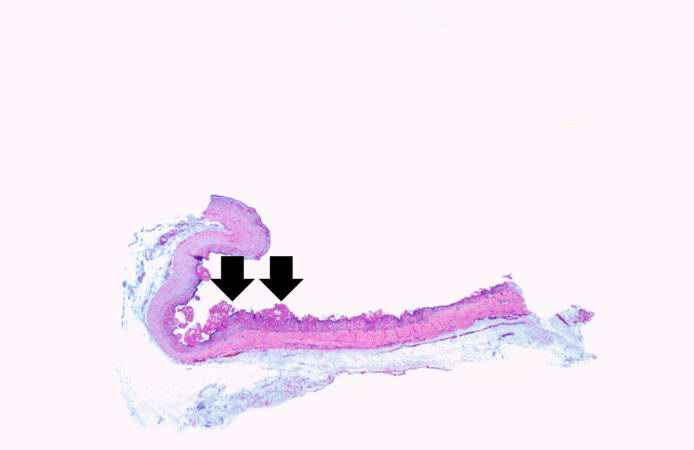

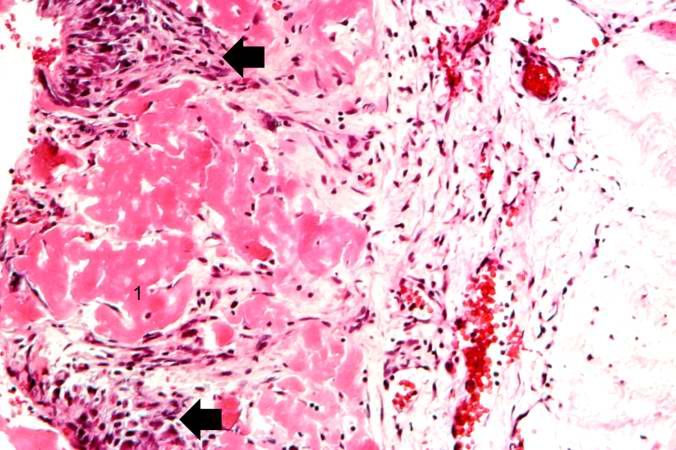

| ====Microscopic Images====

| |

| | |

| [http://www.peir.net Images courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology]

| |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

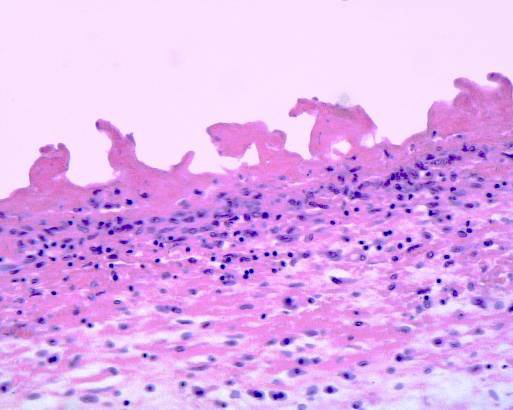

| Image:Pericarditis 0028.jpg|Tuberculous pericarditis.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0029.jpg|Tuberculous pericarditis.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0030.jpg|Tuberculous pericarditis: Micro oil acid fast stain. The organism easily seen.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0031.jpg|Tuberculous pericarditis: Micro oil acid fast stain. The organism easily seen.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0032.jpg|Uremic pericarditis: Micro med mag, H&E. A good example

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0033.jpg|Tuberculous pericarditis: Micro med mag, H&E, a typical lesion

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| <div align="left">

| |

| <gallery heights="175" widths="175">

| |

| Image:Pericarditis 0034.jpg|Fibrinous pericarditis.

| |

| Image:Pericarditis fibrinosa.jpg|Pericarditis fibrinosa (Fibrinous pericarditis).

| |

| Image:Heart in mesothelial tumors 16.jpg|Malignant Mesothelioma, Biphasic Type: Pericardium: This tumor has epithelioid cells (lower half) surrounded by spindled cells. The patient was a 46-year-old woman with constrictive pericarditis; the pericardium was studded with coalescing tumor nodules.

| |

| </gallery>

| |

| </div>

| |

| | |

| | |

| * <Youtube v=AKS7kSl4x5k/>

| |

| | |

| | |

| * Acute fibrinous pericarditis

| |

| | |

| <Youtube v=5fz_W1YxbC8/>

| |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| == Treatment ==

| |

| | |

| The majority of patients with pericarditis are hospitalized so they can be observed and monitored for complications while they recover. The treatment of viral or idiopathic pericarditis is with [[non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug]]s. Patients should be observed for side effects since [[NSAID]]s are known to effect the GI mucosa.

| |

| | |

| Severe cases of pericarditis may require:

| |

| * [[pericardiocentesis]]

| |

| * [[antibiotic]]s

| |

| * [[steroid]]s

| |

| * [[colchicine]]

| |

| * [[surgery]]

| |

| | |

| Patients with uncomplicated acute pericarditis can generally be treated and followed up in an outpatient clinic. However, those with high risk factors for developing complications (see above) will need to be admitted to an inpatient service, most likely an ICU setting. High risk patients include:<!--

| |

| --><ref name="imazio2">{{cite journal | author= Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, Giuggia M, Cecchi E, Gaschino G, Demarie D, Ghisio A, Trinchero R | title= Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy | journal= J Am Coll Cardiol | year=2004 | pages=1042–6 | volume=43 | issue=6 | pmid=15028364 | doi= 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.055}}</ref>

| |

| * subacute onset

| |

| * high fever (> 100.4 F) and [[leukocytosis]]

| |

| * development of [[cardiac tamponade]]

| |

| * large [[pericardial effusion]] (echo-free space > 20 mm) resistant to [[NSAID]] treatment

| |

| * immunocompromised

| |

| * history of oral anticoagulation therapy

| |

| * acute trauma

| |

| * failure to respond to seven days of NSAID treatment.

| |

| | |

| ===Usual Steps in Treatment of Pericarditis===

| |

| | |

| '''''[[Pericardiocentesis]]''''' is a procedure whereby the fluid in a pericardial effusion is removed through a needle. It is performed under the following conditions:<!--

| |

| --><ref name="maisch2">{{cite journal | author= Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, Erbel R, Rienmuller R, Adler Y, Tomkowski WZ, Thiene G, Yacoub MH | title= Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology | journal= Eur Heart J | year=2004 | pages=587–10 | volume=25 | issue=7 | pmid=15120056 | doi= 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.002}}</ref>

| |

| * presence of moderate or severe cardiac tamponade

| |

| * diagnostic purpose for suspected purulent, tuberculosis, or neoplastic pericarditis

| |

| * persistent symptomatic pericardial effusion

| |

| | |

| '''''[[NSAIDs]]''''' in ''viral'' or ''idiopathic'' pericarditis. In patients with underlying causes other than viral, the specific etiology should be treated. With idiopathic or viral pericarditis, NSAID is the mainstay treatment. Goal of therapy is to reduce pain and inflammation. The course of the disease may not be affected. The preferred NSAID is [[ibuprofen]] because of rare side effects, better effect on coronary flow, and larger dose range.<!--

| |

| --><ref name="maisch2">{{cite journal | author= Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, Erbel R, Rienmuller R, Adler Y, Tomkowski WZ, Thiene G, Yacoub MH | title= Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology | journal= Eur Heart J | year=2004 | pages=587–10 | volume=25 | issue=7 | pmid=15120056 | doi= 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.002}}</ref> Depending on severity, dosing is between 300-800 mg every 6-8 hours for days or weeks as needed. An alternative protocol is [[aspirin]] 800 mg every 6-8 hours.<!--

| |

| --><ref name="imazio2">{{cite journal | author= Imazio M, Demichelis B, Parrini I, Giuggia M, Cecchi E, Gaschino G, Demarie D, Ghisio A, Trinchero R | title= Day-hospital treatment of acute pericarditis: a management program for outpatient therapy | journal= J Am Coll Cardiol | year=2004 | pages=1042–6 | volume=43 | issue=6 | pmid=15028364 | doi= 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.055}}</ref> Dose tapering of NSAIDs may be needed. In pericarditis following acute myocardial infarction, NSAIDs other than aspirin should be avoided since they can impair scar formation. As with all NSAID use, GI protection should be engaged. Failure to respond to NSAIDs within one week (indicated by persistence of fever, worsening of condition, new pericardial effusion, or continuing chest pain) likely indicates that a cause other than viral or idiopathic is in process.

| |

| | |

| '''''[[Colchicine]]''''' can be used alone or in conjunction with NSAIDs in prevention of recurrent pericarditis and treatment of recurrent pericarditis. For patients with a first episode of acute idiopathic or viral pericarditis, they should be treated with an NSAID plus colchicine 2 mg on first day followed by 1 mg daily [http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/113/12/1622] for three months. <!--

| |

| --><ref name="adler">{{cite journal | author= Adler Y, Zandman-Goddard G, Ravid M, Avidan B, Zemer D, Ehrenfeld M, Shemesh J, Tomer Y, Shoenfeld Y | title= Usefulness of colchicine in preventing recurrences of pericarditis | journal= Am J of Cardiol | year=1994| pages=916–7 | volume=73 | issue=12 | pmid=8184826 | doi= 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90828-1}}</ref><!--

| |

| --><ref name="imazio3">{{cite journal | author= Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, Demarie D, Demichelis B, Pomari F, Moratti M, Gaschino G, Giammaria M, Ghisio A, Belli R, Trinchero R | title= Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the COlchicine for acute PEricarditis (COPE) trial | journal= Circulation | year=2005| pages=2012–6 | volume=112 | issue=13 | pmid=16186437 | doi= 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.542738}}</ref><!--

| |

| --><ref name="imazio4">{{cite journal | author= Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, Demarie D, Pomari F, Moratti M, Ghisio A, Belli R, Trinchero R | title= Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the CORE (COlchicine for REcurrent pericarditis) trial | journal= Arch Intern Med | year=2005| pages=1987–91 | volume=165 | issue=17 | pmid=16186468 | doi= 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1987}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| '''''[[Corticosteroids]]''''' are usually used in those cases that are clearly refractory to NSAIDs and colchicine and a specific cause has not been found. Systemic corticosteroids are usually reserved for those with autoimmune disease.

| |

| | |

| == Pharmacotherapy ==

| |

| | |

| === Acute Pharmacotherapies ===

| |

| As previously mentioned, the typical pharmacotherapy in viral or idiopathic pericarditis is with [[NSAID]]s. These drugs have analgesic, antipyretic and anti-inflammatory effects. The most prominent members of this group of drugs are [[aspirin]] and [[ibuprofen]]. [[Paracetamol]] ([[acetaminophen]]) has negligible anti-inflammatory activity.

| |

| | |

| === Chronic Pharmacotherapies ===

| |

| Severe cases may require one of the aforementioned procedures or one of the alternative pharmacotherapies listed below:

| |

| :* Antibiotics

| |

| :* Steroids

| |

|

| |

|

| ==Surgical and Device Based Therapies== | | ==Surgical and Device Based Therapies== |