Organism

| Life on Earth Fossil range: Late Hadean - Recent | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Scientific classification | ||

| ||

| Domains and Kingdoms | ||

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [2]

In biology and ecology, an organism (in Greek organon = instrument) is an individual living system (such as animal, plant, fungus or micro-organism). In at least some form, all organisms are capable of reacting to stimuli, reproduction, growth and maintenance as a stable whole (after FAO[1]). An organism may be unicellular or made up, like humans, of many billions of cells divided into specialized tissues and organs.

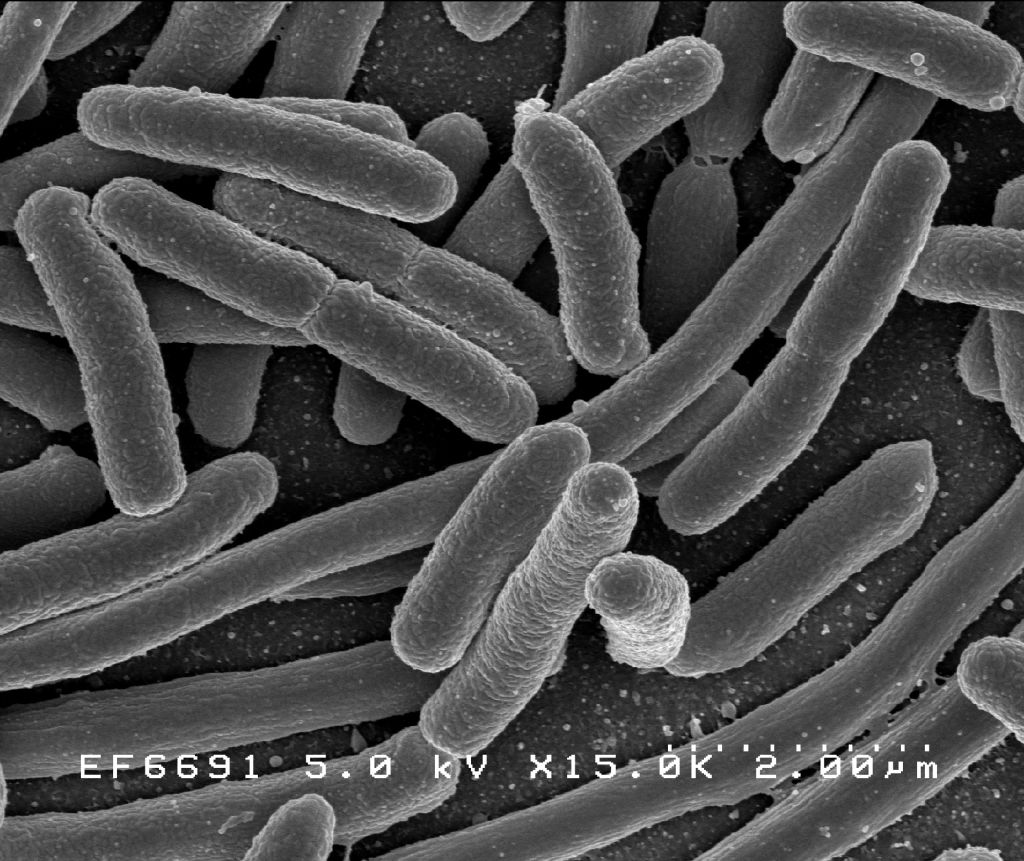

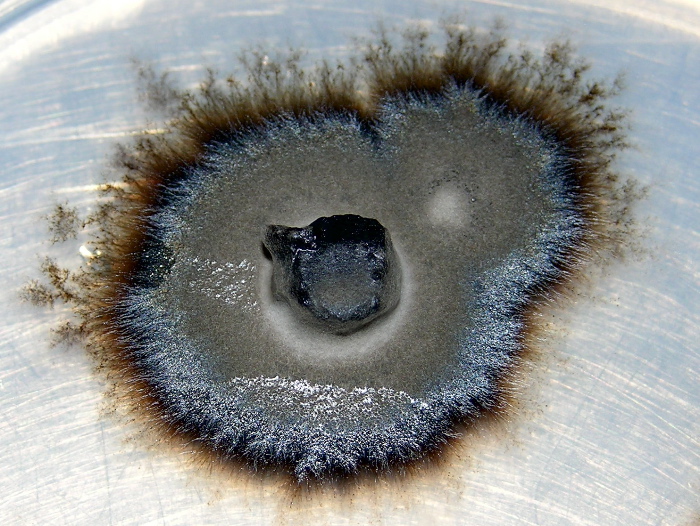

Based on cell type, organisms may be divided into the prokaryotic and eukaryotic groups. The prokaryotes are generally considered to represent two separate domains, called the Bacteria and Archaea, which are not closer to one another than to the eukaryotes. The gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes is widely considered a major missing link in evolutionary history. Eukaryotic organisms, with a membrane-bounded cell nucleus, also contain organelles, namely mitochondria and (in plants) plastids, generally considered to be derived from endosymbiotic bacteria. A similar symbiogenesis hypothesis has been proposed involving the origins of the cell nucleus, it is described as viral eukaryogenesis. Fungi, animals and plants are examples of species that are eukaryotes.

More recently a clade, Neomura, has been proposed, by Thomas Cavalier-Smith, which groups together the Archaea and Eukarya. Cavalier-Smith also proposed that the Neomura evolved from Bacteria, more precisely from Actinobacteria.

The phrase complex organism describes any organism with more than one cell.

Semantics

The word "organism" may broadly be defined as an assembly of molecules that influence each other in such a way that they function as a more or less stable whole and have properties of life. However, many sources, lexical and scientific, add conditions that are problematic to defining the word.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines an organism as "[an] individual animal, plant, or single-celled life form"[2] This definition problematically excludes non-animal and plant multi-cellular life forms such as some fungi and protista. Less controversially, perhaps, it excludes viruses and theoretically-possible man-made non-organic life forms.

Chambers Online Reference provides a much broader definition: "any living structure, such as a plant, animal, fungus or bacterium, capable of growth and reproduction"[3]. The definition emphasises life; it allows for any life form, organic or otherwise, to be considered an organism. This does encompass all cellular life, as well as possible synthetic life. This definition does lack anything approximating to the word "individual" which would exclude viruses. Some may use a definition not including cells. For example its definition might be; a structure that has a DNA. This allows different things by definition to be counted as an organism.

The word "organism" usually describes an independent collections of systems (for example circulatory, digestive, or reproductive) themselves collections of organs; these are, in turn, collections of tissues, which are themselves made of cells.

Viruses

Viruses are not typically considered to be organisms because they are incapable of "independent" reproduction or metabolism. This controversy is problematic, though, since some parasites and endosymbionts are also incapable of independent life. Although viruses have enzymes and molecules characteristic of living organisms, they are incapable of reproducing outside a host cell and most of their metabolic processes require a host and its 'genetic machinery.'

Superorganism

A superorganism is an organism consisting of many organisms. This is usually meant to be a social unit of eusocial animals, where division of labour is highly specialised and where individuals are not able to survive by themselves for extended periods of time. Ants are the most well known example of such a superorganism. Thermoregulation, a feature usually exhibited by individual organisms, does not occur in individuals or small groups of honeybees of the species Apis mellifera. When these bees pack together in clusters of between 5000 and 40000, the colony can thermoregulate.[4] James Lovelock, with his "Gaia Theory" has paralleled the work of Vladimir Vernadsky, who suggested the whole of the biosphere in some respects can be considered as a superorganism.

The concept of superorganism is under dispute, as many biologists maintain that in order for a social unit to be considered an organism by itself, the individuals should be in permanent physical connection to each other, and its evolution should be governed by selection to the whole society instead of individuals. While it's generally accepted that the society of eusocial animals is a unit of natural selection to at least some extent, most evolutionists claim that the individuals are still the primary units of selection.

The question remains "What is to be considered the individual?". Darwinians like Richard Dawkins suggest that the individual selected is the "Selfish Gene". Others believe it is the whole genome of an organism. E.O. Wilson has shown that with ant-colonies and other social insects it is the breeding entity of the colony that is selected, and not its individual members. This could apply to the bacterial members of a stromatolite, which, because of genetic sharing, in some way comprise a single gene pool. Gaian theorists like Lynn Margulis would argue this applies equally to the symbiogenesis of the bacterial underpinnings of the whole of the Earth.

It would appear, from computer simulations like Daisyworld that biological selection occurs at multiple levels simultaneously.

It is also argued that humans are actually a superorganism that includes microorganisms such as bacteria. It is estimated that "the human intestinal microbiota is composed of 1013 to 1014 microorganisms whose collective genome ("microbiome") contains at least 100 times as many genes as our own[...] Our microbiome has significantly enriched metabolism of glycans, amino acids, and xenobiotics; methanogenesis; and 2-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway–mediated biosynthesis of vitamins and isoprenoids. Thus, humans are superorganisms whose metabolism represents an amalgamation of microbial and human attributes." [5].

Organizational terminology

All organisms are classified by the science of alpha taxonomy into either taxa or clades.

Taxa are ranked groups of organisms which run from the general (domain) to the specific (species). A broad scheme of ranks in hierarchical order is:

To give an example, Homo sapiens is the Latin binomial equating to modern humans. All members of the species sapiens are, at least in theory, genetically able to interbreed. Several species may belong to a genus, but the members of different species within a genus are unable to interbreed to produce fertile offspring. Homo, however, only has one surviving species (sapiens); Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis, &c. having become extinct thousands of years ago. Several genera belong to the same family and so on up the hierarchy. Eventually, the relevant kingdom (Animalia, in the case of humans) is placed into one of the three domains depending upon certain genetic and structural characteristics.

All living organisms known to science are given classification by this system such that the species within a particular family are more closely related and genetically similar than the species within a particular phylum.

Chemistry

Organisms are complex chemical systems, organized in ways that promote reproduction and some measure of sustainability or survival. The molecular phenomena of chemistry are fundamental in understanding organisms, but it is a philosophical error (reductionism) to reduce organismal biology to mere chemistry. It is generally the phenomena of entire organisms that determine their fitness to an environment and therefore the survivability of their DNA based genes.

Organisms clearly owe their origin, metabolism, and many other internal functions to chemical phenomena, especially the chemistry of large organic molecules. Organisms are complex systems of chemical compounds which, through interaction with each other and the environment, play a wide variety of roles.

Organisms are semi-closed chemical systems. Although they are individual units of life (as the definition requires) they are not closed to the environment around them. To operate they constantly take in and release energy. Autotrophs produce usable energy (in the form of organic compounds) using light from the sun or inorganic compounds while heterotrophs take in organic compounds from the environment.

The primary chemical element in these compounds is carbon. The physical properties of this element such as its great affinity for bonding with other small atoms, including other carbon atoms, and its small size makes it capable of forming multiple bonds, make it ideal as the basis of organic life. It is able to form small compounds containing three atoms (such as carbon dioxide) as well as large chains of many thousands of atoms which are able to store data (nucleic acids), hold cells together and transmit information (protein).

Macromolecules

The compounds which make up organisms may be divided into macromolecules and other, smaller molecules. The four groups of macromolecule are nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates and lipids. Nucleic acids (specifically deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA) store genetic data as a sequence of nucleotides. The particular sequence of the four different types of nucleotides (adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine) dictate the many characteristics which constitute the organism. The sequence is divided up into codons, each of which is a particular sequence of three nucleotides and corresponds to a particular amino acid. Thus a sequence of DNA codes for a particular protein which, due to the chemical properties of the amino acids of which it is made, folds in a particular manner and so performs a particular function.

The following functions of protein have been recognized:

- Enzymes, which catalyze all of the reactions of metabolism;

- Structural proteins, such as tubulin, or collagen;

- Regulatory proteins, such as transcription factors or cyclins that regulate the cell cycle;

- Signalling molecules or their receptors such as some hormones and their receptors;

- Defensive proteins, which can include everything from antibodies of the immune system, to toxins (e.g., dendrotoxins of snakes), to proteins that include unusual amino acids like canavanine.

Lipids make up the membrane of cells which constitutes a barrier, containing everything within the cell and preventing compounds from freely passing into, and out of, the cell. In some multi-cellular organisms they serve to store energy and mediate communication between cells. Carbohydrates also store and transport energy in some organisms, but are more easily broken down than lipids.

Structure

All organisms consist of monomeric units called cells; some contain a single cell (unicellular) and others contain many units (multicellular). Multicellular organisms are able to specialise cells to perform specific functions, a group of such cells is tissue the four basic types of which are epithelium, nervous tissue, muscle tissue and connective tissue. Several types of tissue work together in the form of an organ to produce a particular function (such as the pumping of the blood by the heart, or as a barrier to the environment as the skin). This pattern continues to a higher level with several organs functioning as an organ system to allow for reproduction, digestion, &c. Many multicelled organisms comprise of several organ systems which coordinate to allow for life.

The cell

The cell theory, first developed in 1839 by Schleiden and Schwann, states that all organisms are composed of one or more cells; all cells come from preexisting cells; all vital functions of an organism occur within cells, and cells contain the hereditary information necessary for regulating cell functions and for transmitting information to the next generation of cells.

There are two types of cells, eukaryotic and prokaryotic. Prokaryotic cells are usually singletons, while eukaryotic cells are usually found in multi-cellular organisms. Prokaryotic cells lack a nuclear membrane so DNA is unbound within the cell, eukaryotic cells have nuclear membranes.

All cells, whether prokaryotic or eukaryotic, have a membrane, which envelopes the cell, separates its interior from its environment, regulates what moves in and out, and maintains the electric potential of the cell. Inside the membrane, a salty cytoplasm takes up most of the cell volume. All cells possess DNA, the hereditary material of genes, and RNA, containing the information necessary to build various proteins such as enzymes, the cell's primary machinery. There are also other kinds of biomolecules in cells.

All cells share several abilities[6]:

- Reproduction by cell division (binary fission, mitosis or meiosis).

- Use of enzymes and other proteins coded for by DNA genes and made via messenger RNA intermediates and ribosomes.

- Metabolism, including taking in raw materials, building cell components, converting energy, molecules and releasing by-products. The functioning of a cell depends upon its ability to extract and use chemical energy stored in organic molecules. This energy is derived from metabolic pathways.

- Response to external and internal stimuli such as changes in temperature, pH or nutrient levels.

- Cell contents are contained within a cell surface membrane that contains proteins and a lipid bilayer.

Life span

One of the basic parameters of organism is its life span. Some animals live as short as one day, while some plants can live thousands of years. Aging is important when determining life span of most organisms, bacterium, a virus or even a prion.

Evolution

In biology, the theory of universal common descent proposes that all organisms on Earth are descended from a common ancestor or ancestral gene pool.

Evidence for common descent may be found in traits shared between all living organisms. In Darwin's day, the evidence of shared traits was based solely on visible observation of morphologic similarities, such as the fact that all birds have wings, even those which do not fly. Today, there is strong evidence from genetics that all organisms have a common ancestor. For example, every living cell makes use of nucleic acids as its genetic material, and uses the same twenty amino acids as the building blocks for proteins. The universality of these traits strongly suggests common ancestry.

The "Last Universal Ancestor" is the name given to the hypothetical single cellular organism or single cell that gave rise to all life on Earth 3.9 to 4.1 billion years ago; however, this hypothesis has since been refuted on many grounds. For example, it was once thought that the genetic code was universal (see: universal genetic code), but differences in the genetic code and differences in how each organism translates nucleic acid sequences into proteins, provide support that there never was any "last universal common ancestor." Back in the early 1970s, evolutionary biologists thought that a given piece of DNA specified the same protein subunit in every living thing, and that the genetic code was thus universal. Since this is something unlikely to happen by chance, it was interpreted as evidence that every organism had inherited its genetic code from a single common ancestor, aka., the "Last Universal Ancestor." In 1979, however, exceptions to the code were found in mitochondria, the tiny energy factories inside cells. Biologists subsequently found exceptions in bacteria and in the nuclei of algae and single-celled animals. It is now clear that the genetic code is not the same in all living things, and that it does not provide powerful evidence that all living things evolved on a single tree of life.[7] Further support that there is no "Last Universal Ancestor" has been provided over the years by Lateral gene transfer in both prokaryote and eukaryote single cell organisms. This is why phylogenetic trees cannot be rooted, why almost all phylogenetic trees have different branching structures, particularly near the base of the tree, and why many organisms have been found with codons and sections of their DNA sequence that are unrelated to any other species.

Information about the early development of life includes input from the fields of geology and planetary science. These sciences provide information about the history of the Earth and the changes produced by life. However, a great deal of information about the early Earth has been destroyed by geological processes over the course of time.

History of life

The chemical evolution from self-catalytic chemical reactions to life (see Origin of life) is not a part of biological evolution, but it is unclear at which point such increasingly complex sets of reactions became what we would consider, today, to be living organisms.

Not much is known about the earliest developments in life. However, all existing organisms share certain traits, including cellular structure and genetic code. Most scientists interpret this to mean all existing organisms share a common ancestor, which had already developed the most fundamental cellular processes, but there is no scientific consensus on the relationship of the three domains of life (Archaea, Bacteria, Eukaryota) or the origin of life. Attempts to shed light on the earliest history of life generally focus on the behavior of macromolecules, particularly RNA, and the behavior of complex systems.

The emergence of oxygenic photosynthesis (around 3 billion years ago) and the subsequent emergence of an oxygen-rich, non-reducing atmosphere can be traced through the formation of banded iron deposits, and later red beds of iron oxides. This was a necessary prerequisite for the development of aerobic cellular respiration, believed to have emerged around 2 billion years ago.

In the last billion years, simple multicellular plants and animals began to appear in the oceans. Soon after the emergence of the first animals, the Cambrian explosion (a period of unrivaled and remarkable, but brief, organismal diversity documented in the fossils found at the Burgess Shale) saw the creation of all the major body plans, or phyla, of modern animals. This event is now believed to have been triggered by the development of the Hox genes. About 500 million years ago, plants and fungi colonized the land, and were soon followed by arthropods and other animals, leading to the development of land ecosystems with which we are familiar.

The evolutionary process may be exceedingly slow. Fossil evidence indicates that the diversity and complexity of modern life has developed over much of the history of the earth. Geological evidence indicates that the Earth is approximately 4.6 billion years old. Studies on guppies by David Reznick at the University of California, Riverside, however, have shown that the rate of evolution through natural selection can proceed 10 thousand to 10 million times faster than what is indicated in the fossil record.[8]. Such comparative studies however are invariably biased by disparities in the time scales over which evolutionary change is measured in the laboratory, field experiments, and the fossil record.

Horizontal gene transfer, and the history of life

The ancestry of living organisms has traditionally been reconstructed from morphology, but is increasingly supplemented with phylogenetics - the reconstruction of phylogenies by the comparison of genetic (DNA) sequence.

"Sequence comparisons suggest recent horizontal transfer of many genes among diverse species including across the boundaries of phylogenetic 'domains'. Thus determining the phylogenetic history of a species can not be done conclusively by determining evolutionary trees for single genes." [9]

Biologist Gogarten suggests "the original metaphor of a tree no longer fits the data from recent genome research", therefore "biologists [should] use the metaphor of a mosaic to describe the different histories combined in individual genomes and use [the] metaphor of a net to visualize the rich exchange and cooperative effects of HGT among microbes." [10]

References

- ↑ {cite http://www.fao.org/biotech/find-formalpha-n.asp

- ↑ "organism". Oxford English Dictionary (online ed.). 2004.

- ↑ "organism". Chambers 21st Century Dictionary (online ed.). 1999.

- ↑ Southwick, Edward E. (1983). "The honey bee cluster as a homeothermic superorganism" (PDF). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 75A (4): 741&ndash, 745. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(83)90434-6. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

- ↑ Gill S. R., et al. Science, 312, 1355-1359 (2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1124234

- ↑ The Universal Features of Cells on Earth in Chapter 1 of Molecular Biology of the Cell fourth edition, edited by Bruce Alberts (2002) published by Garland Science.

- ↑ Edwards, Mark (2001). "PBS Charged with "False Claim" on "Universal Genetic Code". Science, TV Review, & Education Writers. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ↑ Evaluation of the Rate of Evolution in Natural Populations of Guppies (Poecilia reticulata) "[1]"

- ↑ Oklahoma State - Horizontal Gene Transfer

- ↑ esalenctr.org

External links

- BBCNews: 27 September, 2000, When slime is not so thick Citat: "...It means that some of the lowliest creatures in the plant and animal kingdoms, such as slime and amoeba, may not be as primitive as once thought...."

- SpaceRef.com, July 29, 1997: Scientists Discover Methane Ice Worms On Gulf Of Mexico Sea Floor

- The Eberly College of Science: Methane Ice Worms discovered on Gulf of Mexico Sea Floor download Publication quality photos

- Artikel, 2000: Methane Ice Worms: Hesiocaeca methanicola. Colonizing Fossil Fuel Reserves

- SpaceRef.com, May 04, 2001: Redefining "Life as We Know it" Hesiocaeca methanicola In 1997, Charles Fisher, professor of biology at Penn State, discovered this remarkable creature living on mounds of methane ice under half a mile of ocean on the floor of the Gulf of Mexico.

- SpaceRef.com, July 29, 1997: Scientists Discover Methane Ice Worms On Gulf Of Mexico Sea Floor

- BBCNews, 18 December, 2002, 'Space bugs' grown in lab Citat: "...Bacillus simplex and Staphylococcus pasteuri...Engyodontium album...The strains cultured by Dr Wainwright seemed to be resistant to the effects of UV - one quality required for survival in space...."

- BBCNews, 19 June, 2003, Ancient organism challenges cell evolution Citat: "..."It appears that this organelle has been conserved in evolution from prokaryotes to eukaryotes, since it is present in both,"..."

- Interactive Syllabus for General Biology - BI 04, Saint Anselm College, Summer 2003

- Jacob Feldman: Stramenopila

- NCBI Taxonomy entry: root (rich)

- Saint Anselm College: Survey of representatives of the major Kingdoms Citat: "...Number of kingdoms has not been resolved...Bacteria present a problem with their diversity...Protista present a problem with their diversity...",

- Species 2000 Indexing the world's known species. Species 2000 has the objective of enumerating all known species of plants, animals, fungi and microbes on Earth as the baseline dataset for studies of global biodiversity. It will also provide a simple access point enabling users to link from here to other data systems for all groups of organisms, using direct species-links.

- The largest organism in the world may be a fungus carpeting nearly 10 square kilometers of an Oregon forest, and may be as old as 10500 years.

- The Tree of Life.

- Frequent questions from kids about life and their answers

ar:متعضية ast:Ser vivu zh-min-nan:Seng-bu̍t bg:Организъм ca:Organisme cs:Organismus da:Organisme de:Lebewesen et:Organism el:Οργανισμός (βιολογία) eo:Organismo fa:سازواره gl:Organismo ko:생물 hr:Organizam id:Organisme ia:Organismo is:Lífvera it:Organismo vivente he:יצור jv:Organisme kn:ಸಾವಯವ lv:Organisms lb:Liewewiesen lt:Organizmas jbo:jmive hu:Élőlény mk:Организам mg:Zavamanan'aina nl:Organisme no:Organisme nn:Organisme oc:Organisme vivent qu:Kawsaq scn:Organismu simple:Organism sr:Организам su:Organisme fi:Eliö sv:Organism ta:உயிரினம் te:జీవి th:สิ่งมีชีวิต uk:Організм yi:ארגאניסם zh-yue:生物 Template:WH Template:WS Template:Jb1