Subdural hematoma

For patient information click here

| Subdural hematoma | |

|

|---|

|

Subdural Hematoma Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Subdural hematoma On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Subdural hematoma |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

A subdural hematoma (Subdural haematoma) (SDH) is a form of traumatic brain injury in which blood gathers between the dura (the outer protective covering of the brain) and the arachnoid (the middle layer of the meninges). Subdural hemorrhages may cause an increase in intracranial pressure (ICP), which can cause compression of and damage to delicate brain tissue (also known as a mass effect). Acute subdural hematoma (ASDH) has a high mortality rate and is a severe medical emergency.

Pathophysiology

Unlike in epidural hematomas, which are usually caused by tears in arteries, subdural bleeding usually results from tears in veins that cross the subdural space. This bleeding often separates the dura and the arachnoid layers.

Collected blood from the subdural bleed may draw in water due to osmosis, causing it to expand, which may compress brain tissue and cause new bleeds by tearing other blood vessels.[1] The collected blood may even develop its own membrane.[2]

In some subdural bleeds, the arachnoid layer of the meninges is torn, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood both expand in the intracranial space, increasing pressure.[3]

Substances that cause vasoconstriction may be released from the collected material in a subdural hematoma, causing further ischemia under the site by restricting blood flow to the brain.[4] When the brain is denied adequate blood flow, a biochemical cascade known as the ischemic cascade is unleashed, and may ultimately lead to brain cell death.

The body gradually reabsorbs the clot and replaces it with granulation tissue. A subdural hygroma can then develop in which there is no blood but CSF is present.

Classification scheme

Subdural hematomas are divided into acute, subacute, and chronic, depending on their speed of onset. Acute subdural hematomas that are due to trauma are the most lethal of all head injuries and have a high mortality rate if they are not rapidly treated with surgical decompression.

Acute bleeds develop after high speed acceleration or deceleration injuries and are increasingly severe with larger hematomas. They are most severe if associated with cerebral contusions.[5] Though much faster than chronic subdural bleeds, acute subdural bleeding is usually venous and therefore slower than the usually arterial bleeding of an epidural hemorrhage. Acute subdural bleeds have a high mortality rate, higher even than epidural hematomas and diffuse brain injuries, because the velocities necessary to cause them cause other severe injuries as well.[6] The mortality rate associated with acute subdural hematoma is around 60 to 80% [7]

Chronic subdural bleeds develop over the period of days to weeks, often after minor head trauma, though such a cause is not identifiable in 50% of patients.[1] They may not be discovered until they present clinically months or years after a head injury.[8] The bleeding from a chronic bleed is slow, probably from repeated minor bleeds, and usually stops by itself.[3][4] Since these bleeds progress slowly, they present the chance to be stopped before they cause significant damage. Small subdural hematomas, those less than a centimeter wide, have much better outcomes than acute subdural bleeds: in one study, only 22% of patients with chronic subdural bleeds had outcomes worse than "good" or "complete recovery".[5] Chronic subdural hematomas are common in the elderly.[8]

Risk factors

Factors increasing the risk of a subdural hematoma include very young or very old age. As the brain shrinks with age, the subdural space enlarges and the veins that traverse the space must travel over a wider distance, making them more vulnerable to tears. This and the fact that the elderly have more brittle veins make chronic subdural bleeds more common in older patients.[1] Infants, too, have larger subdural spaces and are more predisposed to subdural bleeds than are young adults.[5] For this reason, subdural hematoma is a common finding in shaken baby syndrome. In juveniles, an arachnoid cyst is a risk factor for a subdural hematoma.[9]

Other risk factors for subdural bleeds include taking blood thinners (anticoagulants), long-term alcohol abuse, and dementia.

Differential diagnosis of potential causes

Subdural hematomas are most often caused by head injury, when fast changing velocities within the skull may stretch and tear small bridging veins. Subdural hematomas due to head injury are described as traumatic. Much more common than epidural hemorrhages, subdural hemorrhages generally result from shearing injuries due to various rotational or linear forces.[3][5] It is also commonly seen in the elderly and in alcoholics, who have evidence of brain atrophy. Cerebral atrophy increases the length the bridging veins have to traverse between the two meningeal layers, hence increasing the likelihood of shearing forces causing a tear. It is also more common in patients on anticoagulants, especially aspirin and warfarin. Patients on these medications can have a subdural hematoma with a minor injury.

Diagnosis

It is important that a patient receive medical assessment, including a complete neurological examination, after any head trauma. A CT scan or MRI scan will usually detect significant subdural hematomas.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of subdural hemorrhage have a slower onset than those of epidural hemorrhages because the lower pressure veins bleed more slowly than arteries. Thus, signs and symptoms may show up within 24 hours but can be delayed as much as 2 weeks.[10] If the bleeds are large enough to put pressure on the brain, signs of increased ICP or damage to part of the brain will be present.[5] (Dr.Gill Mohinder MD)

Other signs and symptoms of subdural hematoma include the following:

- A history of recent head injury

- Loss of consciousness or fluctuating levels of consciousness

- Irritability

- Seizures

- Numbness

- Headache (either constant or fluctuating)

- Dizziness

- Disorientation

- Amnesia

- Weakness or lethargy

- Nausea or vomiting

- Personality changes

- Inability to speak or slurred speech

- Ataxia, or difficulty walking

- Altered breathing patterns

- Blurred Vision

- Deviated gaze, or abnormal movement of the eyes.[5]

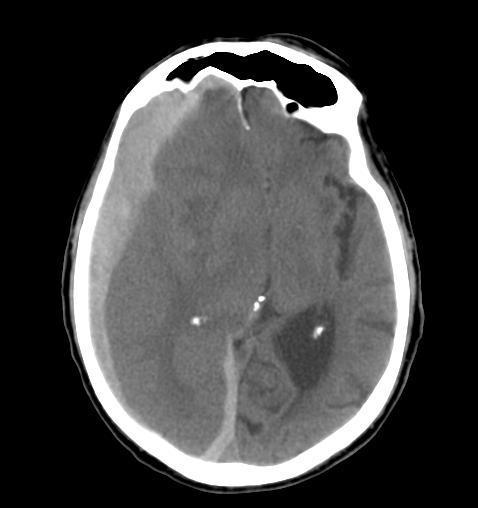

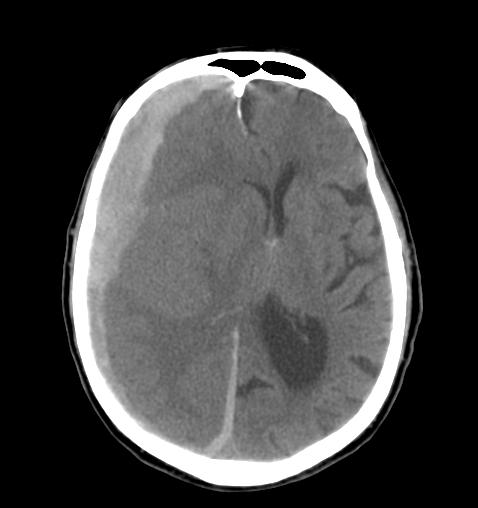

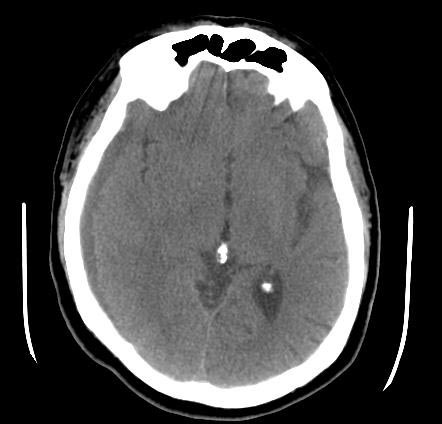

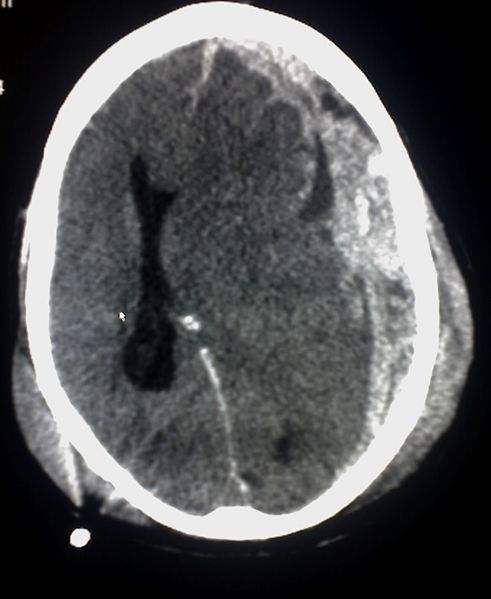

CT and MRI findings

Most of the time, subdural hematomas occur around the tops and sides of the frontal and parietal lobes.[3][5] They also occur in the posterior fossa, and near the falx cerebri and tentorium.[5] Unlike epidural hematomas, which cannot expand past the sutures of the skull, subdural hematomas can expand along the inside of the skull, creating a convex shape that follows the curve of the brain, stopping only at the dural reflections like the tentorium and falx cerebri.

On a CT scan, subdural hematomas are crescent-shaped, with a concave surface away from the skull. Subdural blood can also be seen as a layering density along the tentorium cerebelli. This can be a chronic, stable process, since the feeding system is low-pressure. In such cases, subtle signs of bleeding such as effacement of sulci or medial displacement of the junction between gray matter and white matter may be apparent. A chronic bleed can be the same density as brain tissue (called isodense to brain), meaning that it will show up on CT scan as the same shade as brain tissue, potentially obscuring the finding.

-

CT: Subdural hematoma

-

CT: Subdural hematoma

-

CT: Subdural hematoma

-

CT: Subdural hematoma

-

CT: Subdural hematoma

Treatment

Treatment of a subdural hematoma depends on its size and rate of growth. Small subdural hematomas can be managed by careful monitoring until the body heals itself. Large or symptomatic hematomas require a craniotomy, the surgical opening of the skull. A surgeon then opens the dura, removes the blood clot with suction or irrigation, and identifies and controls sites of bleeding. Postoperative complications include increased intracranial pressure, brain edema, new or recurrent bleeding, infection, and seizure.

See also

- Head injury

- Traumatic brain injury

- Intra-axial hemorrhage

- Extra-axial hemorrhage

- Epidural hematoma

- Subarachnoid hematoma

- Concussion

- Diffuse axonal injury

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Downie A. 2001. "Tutorial: CT in head trauma". Retrieved on August 7, 2007.

- ↑ McCaffrey P. 2001. "The neuroscience on the web series: CMSD 336 neuropathologies of language and cognition." California State University, Chico. Retrieved on August 7, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 University of Vermont College of Medicine. "Neuropathology: Trauma to the CNS." Accessed through web archive on August 8, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Graham DI and Gennareli TA. Chapter 5, "Pathology of brain damage after head injury" Cooper P and Golfinos G. 2000. Head Injury, 4th Ed. Morgan Hill, New York.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Wagner AL. 2004. "Subdural hematoma." Emedicine.com. Retrieved on August 8, 2007.

- ↑ Vinas F.C. and Pilitsis J. 2006. Penetrating Head Trauma. Emedicine.com.

- ↑ Dawodu S. 2004. "Traumatic brain injury: Definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology" Emedicine.com. Retrieved on August 7, 2007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kushner D (1998). "Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Toward Understanding Manifestations and Treatment". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (15): 1617–1624. PMID 9701095.

- ↑ Mori K, Yamamoto T, Horinaka N, Maeda M (2002). "Arachnoid cyst is a risk factor for chronic subdural hematoma in juveniles: twelve cases of chronic subdural hematoma associated with arachnoid cyst". J. Neurotrauma. 19 (9): 1017–27. doi:10.1089/089771502760341938. PMID 12482115.

- ↑ Sanders MJ and McKenna K. 2001. Mosby’s Paramedic Textbook, 2nd revised Ed. Chapter 22, "Head and facial trauma." Mosby.

Template:Cerebral hemorrhage Template:Injuries, other than fractures, dislocations, sprains and strains