Mitral regurgitation pathophysiology

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Associate Editor-In-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [3] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

The pathophysiology of mitral regurgitation can be divided into three phases of the disease process: the acute phase, the chronic compensated phase, and the chronic decompensated phase.

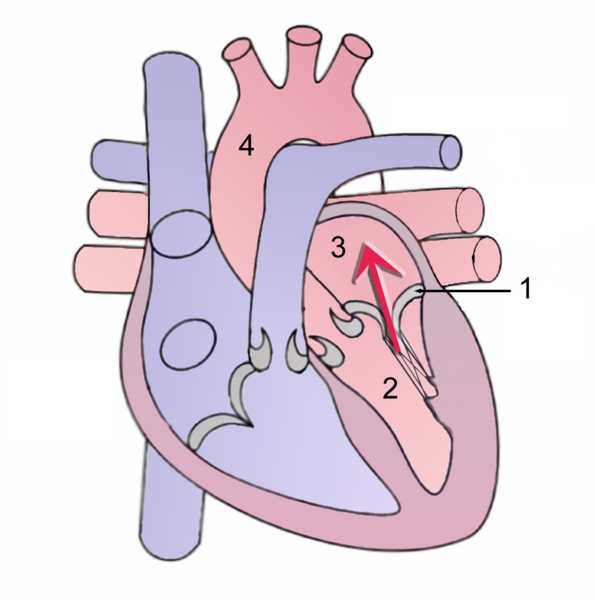

During systole, contraction of the left ventricle causes abnormal backflow (arrow) into the left atrium.

1 Mitral valve

2 Left Ventricle

3 Left Atrium

4 Aorta

Acute phase

Acute mitral regurgitation (as may occur due to the sudden rupture of a chordae tendineae or papillary muscle) causes a sudden volume overload of both the left atrium and the left ventricle.

The left ventricle develops volume overload because with every contraction it now has to pump out not only the volume of blood that goes into the aorta (the forward cardiac output or forward stroke volume), but also the blood that regurgitates into the left atrium (the regurgitant volume).

The combination of the forward stroke volume and the regurgitant volume is known as the total stroke volume of the left ventricle.

In the acute setting, the stroke volume of the left ventricle is increased (increased ejection fraction), but the forward cardiac output is decreased. The mechanism by which the total stroke volume is increased is known as the Frank-Starling mechanism.

The regurgitant volume causes a volume overload and a pressure overload of the left atrium. The increased pressures in the left atrium inhibit drainage of blood from the lungs via the pulmonary veins. This causes pulmonary congestion.

Chronic compensated phase

If the mitral regurgitation develops slowly over months to years or if the acute phase can be managed with medical therapy, the individual will enter the chronic compensated phase of the disease. In this phase, the left ventricle develops eccentric hypertrophy in order to better manage the larger than normal stroke volume.

The eccentric hypertrophy and the increased diastolic volume combine to increase the stroke volume (to levels well above normal) so that the forward stroke volume (forward cardiac output) approaches the normal levels.

In the left atrium, the volume overload causes enlargement of the chamber of the left atrium, allowing the filling pressure in the left atrium to decrease. This improves the drainage from the pulmonary veins, and signs and symptoms of pulmonary congestion will decrease.

These changes in the left ventricle and left atrium improve the low forward cardiac output state and the pulmonary congestion that occur in the acute phase of the disease. Individuals in the chronic compensated phase may be asymptomatic and have normal exercise tolerances.

Chronic decompensated phase

An individual may be in the compensated phase of mitral regurgitation for years, but will eventually develop left ventricular dysfunction, the hallmark for the chronic decompensated phase of mitral regurgitation. It is currently unclear what causes an individual to enter the decompensated phase of this disease. However, the decompensated phase is characterized by calcium overload within the cardiac myocytes.

In this phase, the ventricular myocardium is no longer able to contract adequately to compensate for the volume overload of mitral regurgitation, and the stroke volume of the left ventricle will decrease. The decreased stroke volume causes a decreased forward cardiac output and an increase in the end-systolic volume. The increased end-systolic volume translates to increased filling pressures of the ventricular and increased pulmonary venous congestion. The individual may again have symptoms of congestive heart failure.

The left ventricle begins to dilate during this phase. This causes a dilatation of the mitral valve annulus, which may worsen the degree of mitral regurgitation. The dilated left ventricle causes an increase in the wall stress of the cardiac chamber as well.

While the ejection fraction is less in the chronic decompensated phase than in the acute phase or the chronic compensated phase of mitral regurgitation, it may still be in the normal range (i.e: > 50 percent), and may not decrease until late in the disease course. A decreased ejection fraction in an individual with mitral regurgitation and no other cardiac abnormality should alert the physician that the disease may be in its decompensated phase.

| Acute mitral regurgitation | Chronic mitral regurgitation | |

|---|---|---|

| Electrocardiogram | Normal | P mitrale, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Heart size | Normal | Cardiomegaly, left atrial enlargement |

| Systolic murmur | Heard at the base, radiates to the neck, spine, or top of head | Heard at the apex, radiates to the axilla |

| Apical thrill | May be absent | Present |

| Jugular venous distension | Present | Absent |

Mechanisms of Mitral Regurgitation

- Anterior Leaflet Prolapse

- Posterior Leaflet Prolapse

- Bileaflet Prolapse

- Restricted Leaflets

- Apical Tethering

- Papillary muscle rupture

- Ischemic Papillary Rupture

- Leaflet Perforation