Chagas disease: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

MeshID = D014355 | | MeshID = D014355 | | ||

}} | }} | ||

'''For patient information click [[{{PAGENAME}} (patient information)|here]]''' | |||

{{SI}} | {{SI}} | ||

{{CMG}} | {{CMG}} | ||

Revision as of 15:37, 30 July 2010

| Chagas disease | |

| |

|---|---|

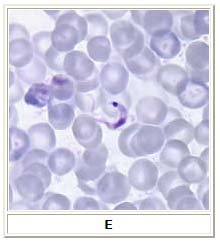

| Photomicrograph of Giemsa-stained Trypanosoma cruzi crithidia (CDC) | |

| ICD-10 | B57 |

| ICD-9 | 086 |

| DiseasesDB | 13415 |

| MedlinePlus | 001372 |

| eMedicine | med/327 |

| MeSH | D014355 |

For patient information click here

|

WikiDoc Resources for Chagas disease |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Chagas disease Most cited articles on Chagas disease |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Chagas disease |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Chagas disease at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Chagas disease Clinical Trials on Chagas disease at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Chagas disease NICE Guidance on Chagas disease

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Chagas disease Discussion groups on Chagas disease Patient Handouts on Chagas disease Directions to Hospitals Treating Chagas disease Risk calculators and risk factors for Chagas disease

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Chagas disease |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Chagas' disease (also called American trypanosomiasis or Trypanosoma cruzi Infection) is a human tropical parasitic disease which occurs in the Americas, particularly in South America. Its pathogenic agent is a flagellate protozoan named Trypanosoma cruzi, which is transmitted to humans and other mammals mostly by blood-sucking assassin bugs of the subfamily Triatominae (Family Reduviidae). Those insects are known by numerous common names varying by country, including benchuca, vinchuca, kissing bug, chipo, chupança and barbeiro. The most common insect species belong to the genera Triatoma, Rhodnius, and Panstrongylus. Other forms of transmission are possible, though, such as ingestion of food contaminated with parasites, blood transfusion and fetal transmission.

The symptoms of Chagas' disease vary over the course of the infection. In the early, acute stage symptoms are mild and are usually no more than local swelling at the site of infection. As the disease progresses, over as much as twenty years, the serious chronic symptoms appear, such as heart disease and malformation of the intestines. If untreated, the chronic disease is often fatal. Current drug treatments for this disease are generally unsatisfactory, with the available drugs being highly toxic and often ineffective, particularly in the chronic stage of the disease.

Trypanosoma cruzi is a member of the same genus as the infectious agent of African sleeping sickness and the same order as the infectious agent of leishmaniasis, but its clinical manifestations, geographical distribution, life cycle and insect vectors are quite different.

History

The disease was named after the Brazilian physician and infectologist Carlos Chagas, who first described it in 1909[1][2][3] but, the disease was not seen as a major public health problem in humans until the 1960s (the outbreak of Chagas' disease in Brazil in the 1920s went widely ignored[4]). He discovered that the intestines of Triatomidae harbored a flagellate protozoan, a new species of the Trypanosoma genus, and was able to prove experimentally that it could be transmitted to marmoset monkeys that were bitten by the infected bug. Later studies showed that squirrel monkeys were also vulnerable to infection.[5]

Chagas named the pathogenic parasite that causes the disease Trypanosoma cruzi [1] and later that year as Schizotrypanum cruzi,[6] both honoring Oswaldo Cruz, the noted Brazilian physician and epidemiologist who fought successfully epidemics of yellow fever, smallpox, and bubonic plague in Rio de Janeiro and other cities in the beginning of the 20th century. Chagas’ work is unique in the history of medicine because he was the only researcher so far to describe completely a new infectious disease: its pathogen, vector, host, clinical manifestations, and epidemiology. Nevertheless, he at least believed falsely until 1925, that the main infection route is by the bite of the insect - and not by its feces, as was proposed by his colleague Emile Brumpt 1915 and assured by Silveira Dias 1932, Cardoso 1938 and Brumpt himself 1939. Chagas was also the first to unknowingly discover and illustrate the parasitic fungal genus Pneumocystis, later to infamously be linked to PCP (Pneumocystis pneumonia in AIDS victims).[2] Confusion between the two pathogens' life-cycles led him to briefly recognize his genus Schizotrypanum, but following the description of Pneumocystis by others as an independent genus, Chagas returned to the use of the name Trypanosoma cruzi.

On another historical point of view, it has been hypothesized that Charles Darwin might have suffered from this disease as a result of a bite of the so-called Great Black Bug of the Pampas (vinchuca) (see Charles Darwin's illness). The episode was reported by Darwin in his diaries of the Voyage of the Beagle as occurring in March 1835 to the east of the Andes near Mendoza. Darwin was young and in general good health though six months previously he had been ill for a month near Valparaiso, but in 1837, almost a year after he returned to England, he began to suffer intermittently from a strange group of symptoms, becoming incapacitated for much of the rest of his life. Attempts to test Darwin's remains at the Westminster Abbey by using modern PCR techniques were met with a refusal by the Abbey's curator.[7]

Epidemiology and geographical distribution

Chagas' disease currently affects 16–18 million people, with some 100 million (25% of the Latin American population) at risk of acquiring the disease,[3] killing around 50,000 people annually.[8] Chronic Chagas' disease remains a major health problem in many Latin American countries, despite the effectiveness of hygienic and preventive measures, such as eliminating the transmitting insects, which have reduced to zero new infections in at least two countries of the region. With increased population movements, however, the possibility of transmission by blood transfusion has become more substantial in the United States.[9] Approximately 500,000 infected people live in the USA, virtually all of them immigrants.[10] Also, T. cruzi has already been found infecting wild opossums and raccoons as far north as the state of North Carolina.[11] Although there are triatomine bugs in the U.S., only rare vectorborne cases of Chagas disease have been documented.

The disease is distributed in the Americas, ranging from the southern United States to southern Argentina, mostly in poor, rural areas of Central and South America.[12]

The disease is almost exclusively found in rural areas, where the Triatominae can breed and feed on the natural reservoirs (the most common ones being opossums and armadillos) of T.cruzi. Depending on the special local interactions of the vectors and their hosts, other infected humans, domestic animals like cats, dogs, guinea pigs and wild animals like rodents, monkeys, ground squirrels (Spermophilus beecheyi) and many others could also serve as important parasite reservoirs. Though Triatominae bugs feed on birds, these seem to be immune against infection and therefore are not considered to be a T. cruzi reservoir; but there remain suspicions of them being a feeding resource for the vectors near human habitations.

The triatomine insects are known popularly in the different countries as vinchuca, barbeiro (the barber), chipo and other names,[3] so called because it sucks the blood at night by biting the face of its victims. The insects, who develop a predominantly domiciliary and anthropophilic behaviour once they have infested a house,[13] usually hide during the day in crevices and gaps in the walls and roofs of poorly constructed homes. More rarely, better constructed houses may harbor the insect vector, because of the use of rough materials for making roofs, such as bamboo and thatch. A mosquito net, wrapped under the mattress, will provide protection in these situations, when the adult insect might sail down from above, but one of the five nymphal stages (instars) could crawl up from the floor.

Even when the colonies of insects are eradicated from a house and surrounding domestic animal shelters, they can arrive again (e.g., by flying) from plants or animals that are part of the ancient, natural sylvatic infection cycle. This can happen especially in zones with mixed open savannah, clumps of trees, etc., interspersed by human habitation.

Dense vegetation, like in tropical rain forests, and urban habitats, are not ideal for the establishment of the human transmission cycle. However, in regions where the sylvatic habitat and its fauna are thinned out by economical exploitation and human habitation, such as in newly deforested, piassava palm (Leopoldinia piassaba) culture areas, and some parts of the Amazon region, this may occur, when the insects are searching for new prey.[14]

Clinical manifestations

The human disease occurs in two stages: the acute stage shortly after the infection, and the chronic stage that may develop over 10 years.

In the acute phase, a local skin nodule called a chagoma can appear at the site of inoculation. When the inoculation site is the conjunctival mucous membranes, the patient may develop unilateral periorbital edema, conjunctivitis, and preauricular lymphadenitis. This constellation of symptoms is referred to as Romaña's sign. The acute phase is usually asymptomatic, but may present symptoms of fever, anorexia, lymphadenopathy, mild hepatosplenomegaly, and myocarditis. The most recognized marker of acute Chagas disease is called Romaña's sign, which includes swelling of the eyelids on the side of the face near the bite wound or where the bug feces were deposited or accidentally rubbed into the eye. Even if symptoms develop during the acute phase, they usually fade away on their own within a few weeks or months. Although the symptoms resolve, the infection, if untreated, persists. Rarely, young children (<5%) die from severe inflammation/infection of the heart muscle (myocarditis) or brain (meningoencephalitis).

Some acute cases (10 to 20%) resolve over a period of 2 to 3 months into an asymptomatic chronic stage (called “chronic indeterminate”)during which few or no parasites are found in the blood. During this time, most people are unaware of their infection. Many people may remain asymptomatic for life and never develop Chagas-related symptoms. However, an estimated 30% of infected people will develop debilitating and sometimes life-threatening medical problems over the course of their lives.

The symptomatic chronic stage may not occur for years or even decades after initial infection. The disease affects the nervous system, digestive system and heart. Chronic infections result in various neurological disorders, including dementia, damage to the heart muscle (cardiomyopathy, the most serious manifestation), and sometimes dilation of the digestive tract (megacolon and megaesophagus), as well as weight loss. Swallowing difficulties may be the first symptom of digestive disturbances and may lead to malnutrition. After several years of an asymptomatic period, 27% of those infected develop cardiac damage, 6% develop digestive damage, and 3% present peripheral nervous involvement. Left untreated, Chagas' disease can be fatal, in most cases due to the cardiomyopathy component.

In people who have suppressed immune systems (for example, due to AIDS or chemotherapy), Chagas disease can reactivate with parasites found in the circulating blood. This occurrence can potentially cause severe disease.

Infection cycle

An infected triatomine insect vector feeds on blood and releases trypomastigotes in its feces near the site of the bite wound. The victim, by scratching the site of the bite, causes trypomastigotes to enter the host through the wound, or through intact mucosal membranes, such as the conjunctiva. Then, inside the host, the trypomastigotes invade cells, where they differentiate into intracellular amastigotes. The amastigotes multiply by binary fission and differentiate into trypomastigotes, then are released into the circulation as bloodstream trypomastigotes. These trypomastigotes infect cells from a variety of biological tissues and transform into intracellular amastigotes in new infection sites. Clinical manifestations and cell death at the target tissues can occur because of this infective cycle. For example, it has been shown by Austrian-Brazilian pathologist Dr. Fritz Köberle in the 1950s at the Medical School of the University of São Paulo at Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, that intracellular amastigotes destroy the intramural neurons of the autonomic nervous system in the intestine and heart, leading to megaintestine and heart aneurysms, respectively.

The bloodstream trypomastigotes do not replicate (unlike the African trypanosomes). Replication resumes only when the parasites enter another cell or are ingested by another vector. The “kissing” bug becomes infected by feeding on human or animal blood that contains circulating parasites. Moreover the bugs might be able to spread the infection to each other through their cannibalistic predatory behaviour. The ingested trypomastigotes transform into epimastigotes in the vector’s midgut. The parasites multiply and differentiate in the midgut and differentiate into infective metacyclic trypomastigotes in the hindgut.

Trypanosoma cruzi can also be transmitted through blood transfusions, organ transplantation, transplacentally, breast milk,[15] and in laboratory accidents. According to the World Health Organization, the infection rate in Latin American blood banks varies between 3% and 53%, a figure higher than of HIV infection and hepatitis B and C.[3]

Children can also acquire Chagas' Disease while still in the womb. Chagas' disease accounts for approximately 13% of stillborn deaths in parts of Brazil. It is recommended that pregnant women be tested for the disease.[16]

Alternative infection mechanism

Researchers suspected since 1991 that the transmission of the trypanosome by the oral route might be possible,[17] due to a number of micro-epidemics restricted to particular times and places (such as a farm or a family dwelling), particularly in non-endemic areas such as the Amazonia (17 such episodes recorded between 1968 and 1997). In 1991, farm workers in the state of Paraíba, Brazil, were apparently infected by contamination of food with opossum feces; and in 1997, in Macapá, state of Amapá, 17 members of two families were probably infected by drinking acai palm fruit juice contaminated with crushed triatomine vector insects.[18] In the beginning of 2005, a new outbreak with 27 cases was detected in Amapá. Despite many warnings in the press and by health authorities, this source of infection continues unabated. In August 2007 the Ministry of Health released the information that in the previous one year and half 15 clusters of Chagas infection in 116 people via ingestion of assai have been detected in the Amazon region [19]

In March 2005, a new startling outbreak was recorded in the state of Santa Catarina, Brazil, that seemed to confirm this alternative mechanism of transmission. Several people in Santa Catarina who had ingested sugar cane juice ("garapa", in Portuguese) by a roadside kiosk acquired Chagas' disease.[20] As of March 30, 2005, 49 cases had been confirmed in Santa Catarina, including 6 deaths. The hypothesized mechanism, so far, is that trypanosome-bearing insects were crushed into the raw preparation. The health authorities of Santa Catarina have estimated that ca. 60,000 people might have had contact with the contaminated food in Santa Catarina and urged everyone in this situation to submit to blood tests. They have prohibited the sale of sugar cane juice in the state until the situation is rectified.

The unusual severity of the disease outbreak has been blamed on a hypothetical higher parasite load achieved by the oral route of infection. Brazilian researchers at the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, were able to infect mice via a gastrointestinal tube with trypanosome-infected oral preparations.

People also can become infected through:

- Consumption of uncooked food contaminated with feces from infected bugs.

- Congenital transmission (from a pregnant woman to her baby).

- Blood transfusion.

- Organ transplantation.

- Accidental laboratory exposure.

It is generally considered safe to breastfeed even if the mother has Chagas disease. However, if the mother has cracked nipples or blood in the breast milk, she should pump and discard the milk until the nipples heal and the bleeding resolves.

Chagas disease is not transmitted from person-to-person like a cold or the flu or through casual contact.

Laboratory diagnosis

Diagnosis of chronic Chagas disease is made after consideration of the patient's clinical findings, as well as by the likelihood of being infected, such as having lived in an endemic country. Diagnosis is generally made by testing with at least two different serologic tests.

Demonstration of the causal agent is the diagnostic procedure in acute Chagas' disease. It almost always yields positive results, and can be achieved by:

- Microscopic examination: a) of fresh anticoagulated blood, or its buffy coat, for motile parasites; and b) of thin and thick blood smears stained with Giemsa, for visualization of parasites; it can be confused with the 50% longer Trypanosoma rangeli, which has not shown any pathogenicity in humans yet.

- Isolation of the agent by: a) inoculation into mice; b) culture in specialized media (e.g., NNN, LIT); and c) xenodiagnosis, where uninfected Reduviidae bugs are fed on the patient's blood, and their gut contents examined for parasites 4 weeks later.

- Various Immunodiagnostic tests; (also trying to distinguish strains (zymodemes) of T.cruzi with divergent pathogenicities).

- Complement fixation

- indirect hemagglutination

- IFA, Indirect fluorescent assay

- RIA, Radio-immunoassay

- ELISA, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- Diagnosis based on Molecular Biology techniques.

- PCR, Polymerase chain reaction, most promising

Antibody Detection:

Infections with Trypanosoma cruzi are common in Mexico, Central America, and South America. Many immigrants from areas where Chagas disease is endemic currently reside in the United States and are potential sources for parasite transmission via contaminated blood. During the acute phase of illness, blood film examination generally reveals the presence of trypomastigotes. During the chronic phase of infection, parasitemia is low; immunodiagnosis is a useful technique for determining whether the patient is infected.

The indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test is available at CDC. IFA antigen slides are prepared from a suspension of epimastigotes. Although IFA is very sensitive, cross-reactivity can occur with sera from patients with leishmaniasis, a protozoan disease that occurs in some of the same geographical areas as T. cruzi. Various serologic methods are commercially available in the U.S. and other countries for laboratory diagnosis of Chagas disease. The sensitivity and specificity of these tests are highly variable.

Prognosis

An index for classification of patients who have Chagas' disease was published in the August 24, 2006 edition of the New England Journal of Medicine.[21] Based on over 500 patients, this index includes clinical aspects, X-ray findings, EKG, echocardiography and Holter.

| Risk factor | points |

|---|---|

| NYHA class III or IV | 5 |

| Cardiomegaly | 5 |

| Wall motion abnormalities | 3 |

| non-sustained ventricular tachycardia | 3 |

| low voltage on ECG | 2 |

| male sex | 2 |

| Total points | Risk of death in 10 years |

|---|---|

| 0–6 | 10% |

| 7–11 | 40% |

| 12–20 | 85% |

Treatment

There are two approaches to therapy, both of which can be life saving:

- antiparasitic treatment, to kill the parasite; and

- symptomatic treatment, to manage the symptoms and signs of infection.

Medication for Chagas' disease is usually only effective when given during the acute stage of infection. The drugs of choice are azole or nitroderivatives such as benznidazole[22] or nifurtimox (under an Investigational New Drug protocol from the CDC Drug Service), but resistance to these drugs has already been reported.[23] Furthermore, these agents are very toxic and have many adverse effects, and cannot be taken without medical supervision. The antifungal agent Amphotericin B has been proposed as a second-line drug, but cost and this drug's relatively high toxicity have limited its use. Moreover, 10-year study of chronic administration of drugs in Brazil has revealed that current chemotherapy does not totally remove parasitemia.[24] Thus, the decision about whether to use antiparasitic therapy should be individualized in consultation with an expert.

In the chronic stage, treatment involves managing the clinical manifestations of the disease, e.g., drugs and heart pacemaker for chronic heart failure and heart arryhthmias; surgery for megaintestine, etc., but the disease per se is not curable in this phase. Chronic heart disease caused by Chagas' disease is now a common reason for heart transplantation surgery. Until recently, however, Chagas' disease was considered a contraindication for the procedure, since the heart damage could recur as the parasite was expected to seize the opportunity provided by the immunosuppression that follows surgery. The research that changed the indication of the transplant procedure for Chagas' disease patients was conducted by Dr. Adib Jatene's group at the Heart Institute of the University of São Paulo, in São Paulo, Brazil.[25] The research noted that survival rates in Chagas' patients can be significantly improved by using lower dosages of the immunosuppressant drug cyclosporin. Recently, direct stem cell therapy of the heart muscle using bone marrow cell transplantation has been shown to dramatically reduce risks of heart failure in Chagas patients.[26] Patients have also been shown to benefit from the strict prevention of reinfection, though the reason for this is not yet clearly understood.

Some examples for the struggle for advances:

- Use of oxidosqualene cyclase inhibitors and cysteine protease inhibitors has been found to cure experimental infections in animals.[27]

- Dermaseptins from frog species Phyllomedusa oreades and P. distincta. Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity without cytotoxicity to mammalian cells.[28]

- Design of inhibitors to enzymes involved in trypanothione metabolism, which is unique to the kinetoplastid group of parasites.[29]

- The sesquiterpene lactone dehydroleucodine (DhL) affects the growth of cultured epimastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi[30]

- The genome of Trypanosoma cruzi has been sequenced.[31] Proteins that are produced by the disease but not by humans have been identified as possible drug targets to defeat the disease.[32]

Prevention

A reasonably effective vaccine was developed in Ribeirão Preto in the 1970s, using cellular and subcellular fractions of the parasite, but it was found economically unfeasible. More recently, the potential of DNA vaccines for immunotherapy of acute and chronic Chagas' disease is being tested by several research groups.

Prevention is centered on fighting the vector (Triatoma) by using sprays and paints containing insecticides (synthetic pyrethroids), and improving housing and sanitary conditions in the rural area. For urban dwellers, spending vacations and camping out in the wilderness or sleeping at hostels or mud houses in endemic areas can be dangerous, a mosquito net is recommended. If the traveller intends to travel to the area of prevalence, he/she should get information on endemic rural areas for Chagas' disease in traveller advisories, such as the CDC.

In most countries where Chagas' disease is endemic, testing of blood donors is already mandatory, since this can be an important route of transmission. The United States FDA has recently licensed a test for antibodies against T. cruzi for use on blood donors but has not yet mandated its use. The AABB recommends that past recipients of blood components from donors found to be infected be notified and themselves tested. In the past, donated blood was mixed with 0,25 g/L of gentian violet successfully to kill the parasites. Early detection and treatment of new cases, including mother-to-baby cases, will also help reduce the burden of disease.

With all these measures, some landmarks were achieved in the fight against Chagas' disease in Latin America: a reduction by 72% of the incidence of human infection in children and young adults in the countries of the Initiative of the Southern Cone, and at least two countries (Uruguay, in 1997, and Chile, in 1999), were certified free of vectorial and transfusional transmission. In Brazil, with the largest population at risk, 10 out of the 12 endemic states were also certified free.

Some stepstones of vector control:

- A yeast trap has been tested for monitoring infestations of certain species of the bugs:"Performance of yeast-baited traps with Triatoma sordida, Triatoma brasiliensis, Triatoma pseudomaculata, and Panstrongylus megistus in laboratory assays."[33]

- Promising results were gained with the treatment of vector habitats with the fungus Beauveria bassiana, (which is also in discussion for malaria- prevention):"Activity of oil-formulated Beauveria bassiana against Triatoma sordida in peridomestic areas in Central Brazil."[34]

- Targeting the symbionts of Triatominae through paratransgenesis.[35]

See also

- Tropical disease

- Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative

- Distinguish from: Chaga mushroom

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chagas C (1909). "Neue Trypanosomen". Vorläufige Mitteilung. Arch. Schiff. Tropenhyg. 13: 120–122.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Redhead SA, Cushion MT, Frenkel JK, Stringer JR (2006). "Pneumocystis and Trypanosoma cruzi: nomenclature and typifications". J Eukaryot Microbiol. 53 (1): 2–11. PMID 16441572.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 WHO. Chagas. Accessed 24 September 2006.

- ↑ "Historical Aspects of American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas' Disease)".

- ↑ Hulsebos LH (1989). "The effect of interleukin-2 on parasitemia and myocarditis in experimental Chagas' disease". Journal of Protozoology. 36 (3): 293–298.

- ↑ Chagas C (1909). "Nova tripanozomiase humana: Estudos sobre a morfolojia e o ciclo evolutivo do Schizotrypanum cruzi n. gen., n. sp., ajente etiolojico de nova entidade morbida do homem". Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1 (2): 159-218 (New human trypanosomiasis. Studies about the morphology and life-cycle of Schizotripanum cruzi, etiological agent of a new morbid entity of man.

- ↑ Adler D (1989). "Darwin's Illness". Isr J Med Sci. 25 (4): 218–21. PMID 2496051.

- ↑ Carlier, Yves. Chagas Disease (American Trypanosomiasis). eMedicine (27 February 2003).

- ↑ Kirchhoff LV. "American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease)—a tropical disease now in the United States." N Engl J Med. 1993 August 26;329(9):639-44. PMID 8341339 Online.

- ↑ National Institutes of Health. Medical Encyclopedia Accessed 9/25/2006

- ↑ Karsten V, Davis C, Kuhn R. "Trypanosoma cruzi in wild raccoons and opossums in North Carolina." J Parasitol. 1992 Jun;78(3):547-9. PMID 1597808

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control (CDC). American Trypanosomyasis Fact Sheet. Accessed 24 September 2006.

- ↑ Grijalva MJ, Palomeque-Rodriguez FS, Costales JA, et al. "High household infestation rates by synanthropic vectors of Chagas disease in southern Ecuador." J Med Entomol. 2005 Jan;42(1):68–74. PMID 15691011

- ↑ Teixeira AR, Monteiro PS, Rebelo JM, et al. "Emerging Chagas Disease: Trophic Network and Cycle of Transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi from Palm Trees in the Amazon." Emerg Infect Dis. 2001 Jan-Feb;7(1):100-12. PMID 11266300. PDF full text.

- ↑ Santos Ferreira C, Amato Neto V, Gakiya E, et al. "Microwave treatment of human milk to prevent transmission of Chagas disease." Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 2003 Jan-Feb;45(1):41-2. PMID 12751321

- ↑ Hudson L, Turner MJ. "Immunological Consequences of Infection and Vaccination in South American Trypanosomiasis [and Discussion]". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, Vol. 307, No. 1131, Towards the Immunological Control of Human Protozoal Diseases. (November 13, 1984), pp. 51–61. JSTOR. Accessed 2/22/07. PMID 6151688

- ↑ Shikanai-Yasuda MA, Marcondes CB, Guedes LA, et al. "Possible oral transmission of acute Chagas disease in Brazil." Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 1991 Sep-Oct;33(5):351-7. PMID 1844961

- ↑ da Silva Valente S, de Costa Valente V, Neto H. "Considerations on the epidemiology and transmission of Chagas disease in the Brazilian Amazon." Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 94 Suppl 1: 395-8. PMID 10677763

- ↑ Açaí faz 1 vítima de Chagas a cada 4 dias na Amazônia. Jornal Folha de São Paulo

- ↑ UK Health Protection Agency (HPA).Chagas’ disease (American trypanosomiasis) in southern Brazil. Accessed 24 September 2006.

- ↑ Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Little W, Xavier S, Rassi S, Rassi A, Rassi G, Hasslocher-Moreno A, Sousa A, Scanavacca M (2006). "Development and validation of a risk score for predicting death in Chagas' heart disease". N Engl J Med. 355 (8): 799–808. PMID 16928995.

- ↑ Garcia S, Ramos CO, Senra JF, et al. "Treatment with benznidazole during the chronic phase of experimental Chagas disease decreases cardiac alterations." Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005 Apr;49(4):1521–8. PMID 15793134 Online

- ↑ Buckner FS, Wilson AJ, White TC, Van Voorhis WC. "Induction of resistance to azole drugs in Trypanosoma cruzi." Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998 Dec;42(12):3245–50. PMID 9835521 Online

- ↑ Lauria-Pires L, Braga MS, Vexenat AC, et al. "Progressive chronic Chagas heart disease ten years after treatment with anti-Trypanosoma cruzi nitroderivatives." Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000 Sep-Oct;63(3-4):111-8. PMID 11388500 PDF Full text

- ↑ Bocchi EA, Bellotti G, Mocelin AO, Uip D, et al. "Heart transplantation for chronic Chagas' heart disease." Ann Thorac Surg. 1996 Jun;61(6):1727–33. PMID 8651775Online

- ↑ Vilas-Boas F, Feitosa GS, Soares MB, Mota A, et al. "[Early results of bone marrow cell transplantation to the myocardium of patients with heart failure due to Chagas disease]." Arq Bras Cardiol. 2006 Aug;87(2):159-66. PMID 16951834 PDF Full text. Also available here.

- ↑ Engel JC, Doyle PS, Hsieh I, McKerrow JH. "Cysteine protease inhibitors cure an experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection." J Exp Med. 1998 August 17;188(4):725-34. PMID 9705954Online.

- ↑ PMID 12379643

- ↑ Fairlamb AH, Cerami A. "Metabolism and functions of trypanothione in the Kinetoplastida." Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:695–729. PMID 1444271

- ↑ Brengio SD, Belmonte SA, Guerreiro E, et al. "The sesquiterpene lactone dehydroleucodine (DhL) affects the growth of cultured epimastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi." J Parasitol. 2000 Apr;86(2):407-12. PMID 10780563

- ↑ El-Sayed NM, Myler PJ, Bartholomeu DC, et al. (2005). "The genome sequence of Trypanosoma cruzi, etiologic agent of Chagas disease". Science 309 (5733): 409-15. PMID 16020725

- ↑ El-Sayed, et al., 2005

- ↑ Pires HH, Lazzari CR, Diotaiuti L, Lorenzo MG. "Performance of yeast-baited traps with Triatoma sordida, Triatoma brasiliensis, Triatoma pseudomaculata, and Panstrongylus megistus in laboratory assays." Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2000 Jun;7(6):384-8. PMID 10949899

- ↑ Luz C, Rocha LF, Nery GV, Magalhaes BP, Tigano MS. "Activity of oil-formulated Beauveria bassiana against Triatoma sordida in peridomestic areas in Central Brazil." Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004 Mar;99(2):211-8. PMID 15250478 Online.

- ↑ "PubMed Search on Triatominae symbiosis".

References

- CDC, Division of Parasitic Diseases. Chagas Disease Fact Sheet. (23 September 2004). Accessed 24 September 2006.

- Dumonteil E, Escobedo-Ortegon J, Reyes-Rodriguez N, Arjona-Torres A, Ramirez-Sierra M (2004). "Immunotherapy of Trypanosoma cruzi infection with DNA vaccines in mice". Infect Immun. 72 (1): 46–53. PMID 14688079.

- CDC, Division of Parasitic Diseases.Chagas Disease(23 October 2007). Accessed 16 August 2007.

- CDC, Division of Parasitic Diseases.Chagas Disease Epidemiology.(23 October 2007). Accessed 16 August 2007.

- CDC, Division of Parasitic Diseases. Treatment(23 October 2007). Accessed 16 August 2007.

Further reading

- Coutinho M (1999). "Ninety years of Chagas disease: a success story at the periphery". Soc Stud Sci. 29 (4): 519–49. PMID 11623933.

- Dias J, Silveira A, Schofield C (2002). "The impact of Chagas disease control in Latin America: a review". Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 97 (5): 603–12. PMID 12219120.

- Kropf S, Azevedo N, Ferreira L (2003). "Biomedical research and public health in Brazil: the case of Chagas' disease (1909–50)". Soc Hist Med. 16 (1): 111–29. PMID 14598820.

- "International Symposium to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the discovery of Chagas disease (Rio de Janeiro, April 11–16, 1999)". Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 94 (Suppl. I). 1999.

- Moncayo A. "Progress towards interruption of transmission of Chagas disease". Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 94 Suppl 1: 401–4. PMID 10677765.

- Prata A. "Evolution of the clinical and epidemiological knowledge about Chagas disease 90 years after its discovery". Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 94 Suppl 1: 81–8. PMID 10677694.

- Franco-Paredes C (2007). "Chagas disease: an impediment in achieving the Millennium Development Goals in Latin America". BMC International Health and Human Rights. 7: 7. PMID 17725836.

- Kevin M. Tyler & Michael A. Miles (ed.). World Class Parasites. Volume 7: American Trypanosomiasis. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 1-4020-7323-2. Amazon review

External links

- VCU Virtual Parasite Project

- All About Chagas Disease, Chagas' disease Information & Prevention, Identification, also in Spanish.

- Chagaspace, also in Spanish.

- ChagMex: Database on-line. UNAM-Instituto de Biología.

- Chagas Disease. PanAmerican Health Organization.

- Disease Information. American Trypanosomiasis or Chagas' Disease. Travel Medicine Program. Health Canada.

- Links to Chagas' Disease pictures (Hardin MD/Univ of Iowa)

- Link to "The Kiss of Death". An anthropological view of Chagas' disease (Joseph Bastien/Univ of Texas at Arlington).

Recent news and events

- Chagas' disease parasite found in desert blood samples

- Chagas Control in the Southern Cone Countries: History of an International Initiative, 1991/2001, PAHO. (Full text e-book)

- Genome Sequencing Project

- Parasites' genetic code 'cracked' From BBC

- Catholic Relief Services. Housing Improvement and Chagas' Disease Prevention Project

- 2006: Nature.com / Scott M. Landfear: Flagella are whip-like structures that power the movement of certain cells. Analysis of a single-cell parasite, the African trypanosome, reveals that flagella are also essential for viability in this organism. (restricted commercial access now)

- Science Magazine Search Results: Chagas

Template:Protozoal diseases Template:SIB

Template:Link FA

ar:شاجاس

ca:Malaltia de Chagas

de:Chagas-Krankheit

it:Malattia di Chagas

lt:Čagaso liga

ms:Penyakit Cagas

nl:Ziekte van Chagas

sv:Chagas sjukdom