Tongue cancer pathophysiology

|

Tongue cancer Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Tongue cancer pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Tongue cancer pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Tongue cancer pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Simrat Sarai, M.D. [2] Mohammed Abdelwahed M.D[3]

Overview

Leukoplakia and erythroplakia have the greatest potential for malignant transformation in tongue cancer. World Health Organization classified oral cancer into mild, moderate, and severe dysplasia. Genes involved in the pathogenesis of tongue cancer include TP53, c-myc, and erb-b1. On gross pathology, exophytic, ulcerative, and infiltarative growth patterns are characteristic findings of tongue cancer. Tongue cancer constitutes of highly differentiated squamous cells lacking frank cytologic criteria of malignancy with rare mitoses. The surface of the lesion is covered with compressed invaginating folds of keratin layers. A stroma-like inflammatory reaction and a blunt pushing margin may be seen.

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis

- The two most common types of precancerous conditions on the tongue are called leukoplakia and erythroplakia and they can usually be easily spotted by a dentist.

- Leukoplakia and erythroplakia have the greatest potential for malignant transformation into tongue cancer.[1]

- Leukoplakia is defined as a white patch of the mucosa that cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other disease.

- Leukoplakia is considered a premalignant condition from the chronic irritation of the mucous membranes, resulting in increased rates of epithelial and connective tissue proliferation.

- Leukoplakia usually occurs after the age of 40 years, with the peak incidence before age 50 years.

- Leukoplakia is 2-3 times more common in men than in women.

- The rates of malignant transformation of leukoplakia lesions range from less than 1% to as high as 17.5%, averaging 4.5-6%.

- Erythroleukoplakia and nodular leukoplakia exhibit the highest rate of malignant transformation.

- Erythroplakia is defined as a red, velvety plaque found on the oral mucosa that cannot be ascribed to any other predetermined condition.

- No sex predilection is recognized in erythroplakia and it is rarely found on the tongue compared with other sites in the oral cavity.

- Erythroplakia is considered as the earliest sign of asymptomatic cancer by Mashberg.[2]

World Health Organization grading for oral cancer dysplasia:

- Mild dysplasia: Abnormal cytological features largely confined to the lower third of the epithelium.[3]

- Moderate dysplasia: The dysplastic process extends into the middle third of the epithelium.

- Severe dysplasia: Extension of the dysplasia into the upper third of the epithelium.

- Carcinoma in-situ: Full thickness involvement is present in the absence of invasion.

Tumor spread

Local spread

- Floor of mouth SCC spreads superficially without invading into the mylohyoid muscle or the sublingual gland until a late stage.

- Tumor involving the lateral margin of tongue tends to spread in depth.

- The intrinsic muscles of tongue run in all directions.

- Tumors of palate spread superficially rather than in depth.

Lymphatic spread

- The mechanism of spread from the primary site to lymph nodes is almost always by embolism or by permeation.

- Spread to local lymph nodes worsens the prognosis in oral and oropharyngeal cancer.

- The lymph nodes in the neck are divided into levels. Levels at high risk for metastasis from oral cavity SCC are Levels I, II and III, and to a lesser extent Level IV.

Hematogenous spread

- Hematogenous spread is less important than local and lymphatic spread.

- The best predictor of the likelihood of this spread is involvement of the neck at multiple levels.

- This suggests that the route of entry of tumors into the circulation is most often via the large veins in the neck and that hematogenous spread is in effect tertiary spread following extracapsular spread from neck lymph nodes.

Genetics

- Genes involved in the pathogenesis of tongue cancer include TP53, which is located on chromosome 17.[4]

- The carcinogens in tobacco smoke, for example, increase the prevalence and spectrum of TP53 mutations.[5]

- Other oncogenes associated with squamous cell cancers of the tongue include c-myc and erb -b1.

- More than 50% of oropharyngeal carcinomas harbour integrated HPV DNA.

- The E6 and E7 viral oncoproteins bind and inactivate the TP53 and retinoblastoma gene products respectively, disengaging two of the more critical pathways involved in cell cycle regulation.

- Local tumor recurrence reflects extension of genetically damaged cells beyond the clinical and microscopic boundaries of carcinoma to the margins of surgical resection.[6]

- Head and neck SCC have been identified by circulating plasma or serum changes which can be used for follow-up and screening.

Gross pathology

- Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy of the tongue.

- It typically has three gross morphologic growth patterns: exophytic, ulcerative, and infiltrative.

- The infiltrative and ulcerative are the types most commonly observed on the tongue.

- The macroscopic appearance of tongue cancer depends on the following:

- Duration of the lesion

- The amount of keratinization

- The changes in the adjoining mucosa

- A fully developed tongue lesion appears as an exophytic bulky lesion that is gray to grayish-red and has a rough, shaggy, or papillomatous surface.

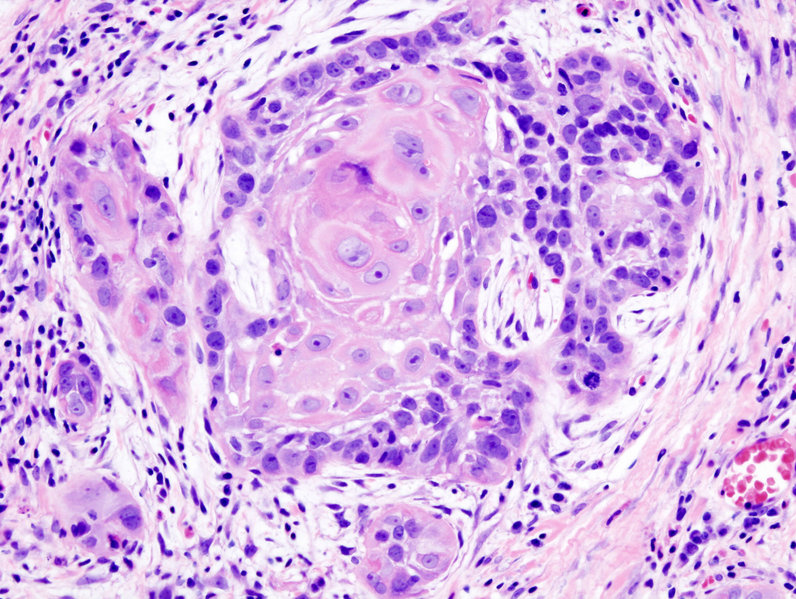

Microscopic Pathology

- Microscopically, tongue cancers are broadly based and invasive through papillary fronds.

- Tongue cancer constitutes of highly differentiated squamous cells lacking frank cytologic criteria of malignancy with rare mitoses.

- The surface of the lesion is covered with compressed invaginating folds of keratin layers. A stroma-like inflammatory reaction and a blunt pushing margin may be seen.

- SCC is subdivided by the WHO into:[7]

- Keratinizing type: Worst prognosis.

- Undifferentiated type: Intermediate prognosis, EBV association.[8]

- Nonkeratinizing type: Good prognosis, EBV association.

References

- ↑ Abbey LM (1991). "Precancerous lesions of the mouth". Curr Opin Dent. 1 (6): 773–6. PMID 1807482.

- ↑ A. Mashberg (1978). "Erythroplasia: the earliest sign of asymptomatic oral cancer". Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 96 (4): 615–620. PMID 0273632.

- ↑ Lee CC, Ho HC, Su YC, Yu CH, Yang CC (2015). "Modified Tumor Classification With Inclusion of Tumor Characteristics Improves Discrimination and Prediction Accuracy in Oral and Hypopharyngeal Cancer Patients Who Underwent Surgery". Medicine (Baltimore). 94 (27): e1114. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001114. PMC 4504658. PMID 26166107.

- ↑ Abbas NF, Labib El-Sharkawy S, Abbas EA, Abdel Monem El-Shaer M (2007). "Immunohistochemical study of p53 and angiogenesis in benign and preneoplastic oral lesions and oral squamous cell carcinoma". Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 103 (3): 385–90. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.11.008. PMID 17321451.

- ↑ Stelow EB, Jo VY, Stoler MH, Mills SE (2010). "Human papillomavirus-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract". Am J Surg Pathol. 34 (7): e15–24. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e21478. PMID 20534998.

- ↑ Schlecht NF, Brandwein-Gensler M, Nuovo GJ, Li M, Dunne A, Kawachi N; et al. (2011). "A comparison of clinically utilized human papillomavirus detection methods in head and neck cancer". Mod Pathol. 24 (10): 1295–305. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2011.91. PMC 3157570. PMID 21572401.

- ↑ Peterson BR, Nelson BL (2013). "Nonkeratinizing undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma". Head Neck Pathol. 7 (1): 73–5. doi:10.1007/s12105-012-0401-4. PMC 3597164. PMID 23015393.

- ↑ Pathmanathan R, Prasad U, Chandrika G, Sadler R, Flynn K, Raab-Traub N (1995). "Undifferentiated, nonkeratinizing, and squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Variants of Epstein-Barr virus-infected neoplasia". Am J Pathol. 146 (6): 1355–67. PMC 1870892. PMID 7778675.