Sorbitol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

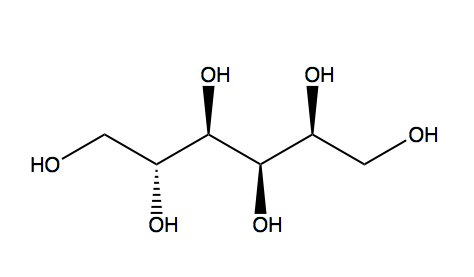

| IUPAC name

(2S,3R,4R,5R)-Hexane-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexol

| |

| Other names

D-glucitol; D-Sorbitol; Sorbogem; Sorbo

| |

| Identifiers | |

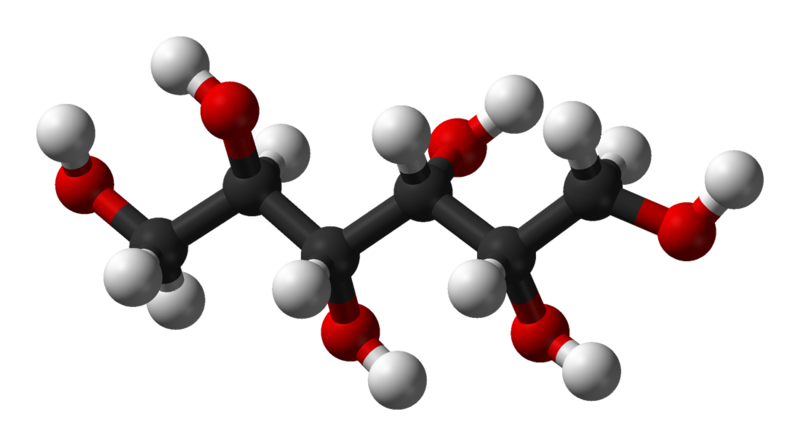

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | Lua error in Module:Wikidata at line 879: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). Lua error in Module:Wikidata at line 879: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

| MeSH | Sorbitol |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H14O6 | |

| Molar mass | 182.17 g/mol |

| Hazards | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

|

WikiDoc Resources for Sorbitol |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Sorbitol |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Sorbitol at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Sorbitol at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Sorbitol

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Sorbitol Risk calculators and risk factors for Sorbitol

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Sorbitol |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Sorbitol, also known as glucitol, is a sugar alcohol with a sweet taste which the human body metabolizes slowly. It can be obtained by reduction of glucose, changing the aldehyde group to a hydroxyl group. Most sorbitol is made from corn syrup, but it is also found in apples, pears, peaches, and prunes.[1] It is converted to fructose by Sorbitol-6-phosphate 2-dehydrogenase. Sorbitol is an isomer of mannitol, another sugar alcohol; the two differ only in the orientation of the hydroxyl group on carbon 2.[2] While similar, the two sugar alcohols have very different sources in nature, melting points, and uses.

Uses

Sweetener

Sorbitol is a sugar substitute. It may be listed under the inactive ingredients listed for some foods and products. Its INS number and E number is 420. Sorbitol has approximately 60% the sweetness of sucrose (table sugar).[3]

Sorbitol is referred to as a nutritive sweetener because it provides dietary energy: 2.6 kilocalories (11 kilojoules) per gram versus the average 4 kilocalories (17 kilojoules) for carbohydrates. It is often used in diet foods (including diet drinks and ice cream), mints, cough syrups, and sugar-free chewing gum.[4]

It also occurs naturally in many stone fruits and berries from trees of the genus Sorbus.[5]

Laxative

Sorbitol can be used as a non-stimulant laxative via an oral suspension or enema. As with other sugar alcohols, gastrointestinal distress may result when food products that contain sorbitol are consumed. Sorbitol exerts its laxative effect by drawing water into the large intestine, thereby stimulating bowel movements.[6] Sorbitol has been determined safe for use by the elderly, although it is not recommended without consultation with a clinician.[7] Sorbitol is found in some dried fruits and may contribute to the laxative effects of prunes.[8] Sorbitol was discovered initially in the fresh juice of mountain ash berries in 1872.[9] It is found in the fruits of apples, plums, pears, cherries, dates, peaches, and apricots.

Medical applications

Sorbitol is used in bacterial culture media to distinguish the pathogenic Escherichia coli O157:H7 from most other strains of E. coli, as it is usually incapable of fermenting sorbitol, but 93% of known E. coli strains are capable of doing so.[10]

A treatment using sorbitol and ion-exchange resin sodium polystyrene sulfonate (tradename Kayexalate), helps remove excess potassium ions when in a hyperkalaemic state.[11] The resin exchanges sodium ions for potassium ions in the bowel, while sorbitol helps to eliminate it. In 2010 the U.S. FDA issued a warning of increased risk for GI necrosis with this combination.[12]

Health care, food, and cosmetic uses

Sorbitol often is used in modern cosmetics as a humectant and thickener.[13] Sorbitol often is used in mouthwash and toothpaste. Some transparent gels can be made only with sorbitol, as it has a refractive index sufficiently high for transparent formulations. It is also used frequently in "sugar free" chewing gum.

Sorbitol is used as a cryoprotectant additive (mixed with sucrose and sodium polyphosphates) in the manufacture of surimi, a highly refined fish paste most commonly produced from Alaska pollock (Theragra chalcogramma). [citation needed] It is also used as a humectant in some cigarettes.[14]

Sorbitol sometimes is used as a sweetener and humectant in cookies and other foods that are not identified as "dietary" items.

Miscellaneous uses

A mixture of sorbitol and potassium nitrate has found some success as an amateur solid rocket fuel.[15]

Sorbitol is identified as a potential key chemical intermediate[16] for production of fuels from biomass resources. Carbohydrate fractions in biomass such as cellulose undergo sequential hydrolysis and hydrogenation in the presence of metal catalysts to produce sorbitol.[17] Complete reduction of sorbitol opens the way to alkanes, such as hexane, which can be used as a biofuel. Hydrogen required for this reaction can be produced by aqueous phase reforming of sorbitol.[18]

- 19 C6H14O6 → 13 C6H14 + 36 CO2 + 42 H2O

The above chemical reaction is exothermic; 1.5 moles of sorbitol generate approximately 1 mole of hexane. When hydrogen is co-fed, no carbon dioxide is produced.

It is also added after electroporation of yeasts in transformation protocols, allowing the cells to recover by raising the osmolarity of the medium.

Medical importance

Aldose reductase is the first enzyme in the sorbitol-aldose reductase pathway[19] responsible for the reduction of glucose to sorbitol, as well as the reduction of galactose to galactitol. Too much sorbitol trapped in retinal cells, the cells of the lens, and the Schwann cells that myelinate peripheral nerves can damage these cells, leading to retinopathy, cataracts and peripheral neuropathy, respectively. Aldose reductase inhibitors, which are substances that prevent or slow the action of aldose reductase, are currently being investigated as a way to prevent or delay these complications, which frequently occur in the setting of long-term hyperglycemia that accompanies poorly controlled diabetes. It is thought that these agents may help to prevent the accumulation of intracellular sorbitol that leads to cellular damage in diabetics.[20]

Adverse medical effects

Sorbitol may aggravate irritable bowel syndrome[21] and similar gastrointestinal conditions, resulting in severe abdominal pain for those affected, even from small amounts ingested.

It has been noted that the sorbitol added to SPS (sodium polystyrene sulfonate, used in the treatment of hyperkalemia) can cause complications in the GI tract, including bleeding, perforated colonic ulcers, ischemic colitis and colonic necrosis, particularly in patients with uremia. The authors of the paper in question cite a study on rats (both non-uremic and uremic) in which all uremic rats died on a sorbitol enema regimen, whilst uremic rats on non-sorbitol regimens - even with SPS included - showed no signs of colonic damage. In humans, it is suggested that the risk factors for sorbitol-induced damage include "... immunosuppression, hypovolemia, postoperative setting, hypotension after hemodialysis, and peripheral vascular disease." They conclude that SPS-sorbitol should be used with caution, and that "Physicians need to be aware of SPS-sorbitol GI side effects while managing hyperkalemia." [22]

Overdose effects

Ingesting large amounts of sorbitol can lead to abdominal pain, flatulence, and mild to severe diarrhea.[23] Sorbitol ingestion of 20 grams (0.7 oz) per day as sugar-free gum has led to severe diarrhea leading to unintended weight loss of 11 kilograms (24 lb) in eight months, in a woman originally weighing 52 kilograms (115 lb); another patient required hospitalization after habitually consuming 30 grams (1 oz) per day.[24]

Compendial status

See also

References

- ↑ Teo, G; Suzuki, Y; Uratsu, SL; Lampinen, B; Ormonde, N; Hu, WK; Dejong, TM; Dandekar, AM (2006). "Silencing leaf sorbitol synthesis alters long-distance partitioning and apple fruit quality". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (49): 18842–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605873103. PMC 1693749. PMID 17132742.

- ↑ Kearsley, M. W.; Deis, R. C. Sorbitol and Mannitol. In Sweeteners and Sugar Alternatives in Food Technology; Ames: Oxford, 2006; pp 249-249-261.

- ↑ Sugar substitute

- ↑ Campbell; Farrell (2011). Biochemistry (Seventh ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-1-111-42564-7.

- ↑ Nelson; Cox (2005). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (Fourth ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- ↑ ACS :: Cancer Drug Guide: sorbitol

- ↑ Lederle, FA (1995). "Epidemiology of constipation in elderly patients. Drug utilisation and cost-containment strategies". Drugs & aging. 6 (6): 465–9. doi:10.2165/00002512-199506060-00006. PMID 7663066.

- ↑ Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis, M; Bowen, PE; Hussain, EA; Damayanti-Wood, BI; Farnsworth, NR (2001). "Chemical composition and potential health effects of prunes: a functional food?". Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 41 (4): 251–86. doi:10.1080/20014091091814. PMID 11401245.

- ↑ Panda, H. (2011). The Complete Book on Sugarcane Processing and By-Products of Molasses (with Analysis of Sugar, Syrup and Molasses). ASIA PACIFIC BUSINESS PRESS Inc. p. 416. ISBN 8178331446.

- ↑ Wells JG, Davis BR, Wachsmuth IK; et al. (September 1983). "Laboratory investigation of hemorrhagic colitis outbreaks associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype". Journal of clinical microbiology. 18 (3): 512–20. PMC 270845. PMID 6355145.

The organism does not ferment sorbitol; whereas 93% of E. coli of human origin are sorbitol positive

- ↑ Rugolotto S, Gruber M, Solano PD, Chini L, Gobbo S, Pecori S (April 2007). "Necrotizing enterocolitis in a 850 gram infant receiving sorbitol-free sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate): clinical and histopathologic findings". J Perinatol. 27 (4): 247–9. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211677. PMID 17377608.

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm186845.htm

- ↑ http://www.bttcogroup.in/sorbitol-70.html

- ↑ Gallaher Group Plc - Ingredients

- ↑ Richard Nakka's Experimental Rocketry Web Site

- ↑ Metzger, Jürgen O. (2006). "Production of Liquid Hydrocarbons from Biomass". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 45 (5): 696–698. doi:10.1002/anie.200502895.

- ↑ Shrotri, Abhijit; Tanksale, Akshat; Beltramini, Jorge Norberto; Gurav, Hanmant; Chilukuri, Satyanarayana V. (2012). "Conversion of cellulose to polyols over promoted nickel catalysts". Catalysis Science & Technology. 2 (9): 1852–1858. doi:10.1039/C2CY20119D.

- ↑ Tanksale, Akshat; Beltramini, Jorge Norberto; Lu, GaoQing Max (2010). "A review of catalytic hydrogen production processes from biomass". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 14 (1): 166–182. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2009.08.010.

- ↑ Nishikawa, T; Edelstein, D; Du, XL; Yamagishi, S; Matsumura, T; Kaneda, Y; Yorek, MA; Beebe, D; et al. (2000). "Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage". Nature. 404 (6779): 787–90. doi:10.1038/35008121. PMID 10783895.

- ↑ Sorbitol: a hazard for diabetics? Nutrition Health Review

- ↑ Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Causes and Treatment - What can aggravate my symptoms?

- ↑ http://www.practicalgastro.com/pdf/November10/ErfaniArticle.pdf

- ↑ Islam, MS; Sakaguchi, E (2006). "Sorbitol-based osmotic diarrhea: possible causes and mechanism of prevention investigated in rats". World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 12 (47): 7635–41. PMID 17171792.

- ↑ Kathleen Doheny (2008-01-10). "Sweetener Side Effects: Case Histories". WebMD Medical News. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ↑ Sigma Aldrich. "D-Sorbitol". Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ↑ European Pharmacopoeia. "Index, Ph Eur" (PDF). Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ↑ British Pharmacopoeia (2009). "Index, BP 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 6 July 2009.

External links

- Sorbitol bound to proteins in the PDB

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- Articles without KEGG source

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Chembox

- Articles with changed EBI identifier

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- Chembox image size set

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2007

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Excipients

- Laxatives

- Osmotic diuretics

- Sugar alcohols

- Sweeteners