Influenza causes

|

Influenza Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Influenza causes On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Influenza causes |

For more information about non-human (variant) influenza viruses that may be transmitted to humans, see Zoonotic influenza

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [2]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Alejandro Lemor, M.D. [3]

Overview

Influenza infection is caused by the influenza virus that belong to the family Orthomyxoviridae. Three types of influenza virus have been reported to cause clinical illness in humans: types A, B, and C. Influenza virus can be found in humans, as well as in poultry, pigs, and bats.

Taxonomy

Viruses; ssRNA viruses; ssRNA negative-strand viruses; Orthomyxoviridae; Influenzavirus A; Influenza A virus[1]

Viruses; ssRNA viruses; ssRNA negative-strand viruses; Orthomyxoviridae; Influenzavirus B; Influenza B virus[1]

Viruses; ssRNA viruses; ssRNA negative-strand viruses; Orthomyxoviridae; Influenzavirus C; Influenza C virus[1]

- Orthomyxoviridae

- Influenzavirus A

- Influenza A virus

- (many subtypes)

- Influenzavirus B

- Influenza B virus

- (many subtypes)

- Influenzavirus C

- Influenza C virus

- (many subtypes)

- The international naming convention for influenza viruses uses the following components to name the virus:[2]

- The antigenic type (A, B, C)

- The host of origin (Swine, equine, chicken, etc. For human-origin viruses, no host of origin designation is given.)

- Geographical origin (e.g., Hong Kong, Denver, Taiwan)

- Strain number (e.g., 15, 7)

- Year of isolation (e.g., 57, 2009)

- For influenza A viruses, the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase antigen description in parentheses (e.g.,(H1N1), (H5N1)).

Influenza A

- Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes based on two proteins on the surface of the virus: the hemagglutinin (H) and the neuraminidase (N).

- There are 18 different hemagglutinin subtypes and 11 different neuraminidase subtypes. (H1 through H18 and N1 through N11 respectively.)

- Influenza A viruses can be further broken down into different strains.

- Current subtypes of influenza A viruses found in people are influenza A (H1N1) and influenza A (H3N2) viruses.

- In the spring of 2009, a new influenza A (H1N1) virus (CDC 2009 H1N1 Flu website) emerged to cause illness in people.

- This virus was very different from the human influenza A (H1N1) viruses circulating at that time.

- The new virus caused the first influenza pandemic in more than 40 years.

- That virus (often called “2009 H1N1”) has now replaced the H1N1 virus that was previously circulating in humans.

Influenza B

- Influenza B viruses are not divided into subtypes, but can be further broken down into lineages and strains.

- Currently circulating influenza B viruses belong to one of two lineages: B/Yamagata and B/Victoria.

Structure

|

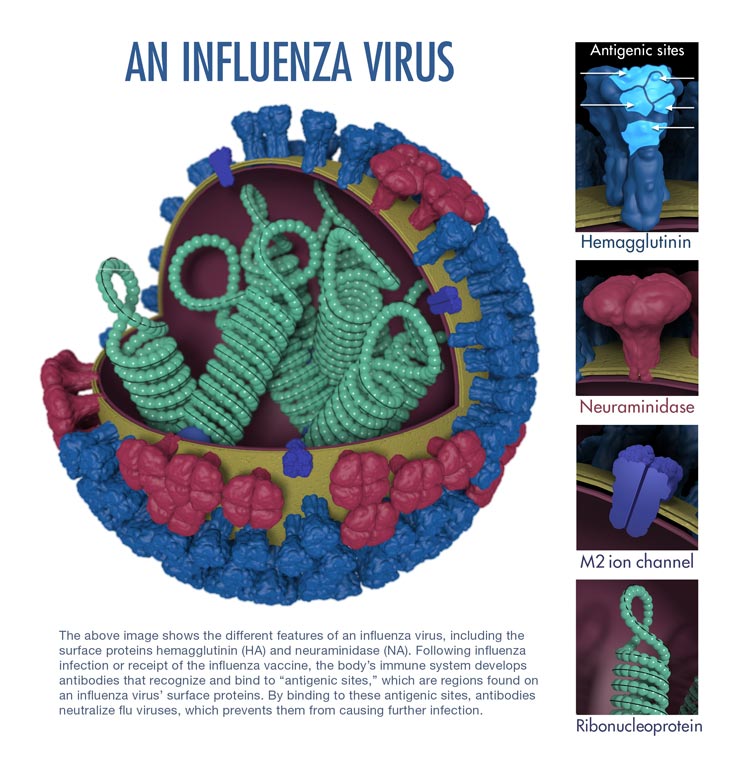

- Influenza viruses (A, B and C) are very similar in overall structure, they arre single-stranded, enveloped, negative-sense RNA viruses.

- Influenza virus replicate inside the nucleus of the host-cell.

- The virus particle is 80–120 nanometers in diameter and usually roughly spherical, although filamentous forms can occur.[3][4]

- These filamentous forms are more common in influenza C, which can form cordlike structures up to 500 micrometers long on the surfaces of infected cells.

- The viral envelope contains two main types of glycoproteins, wrapped around a central core.

- The central core contains the viral RNA genome and other viral proteins that package and protect this RNA.

- RNA tends to be single stranded but in special cases it is double.[4] Unusually for a virus, its genome is not a single piece of nucleic acid; instead, it contains seven or eight pieces of segmented negative-sense RNA, each piece of RNA containing either one or two genes, which code for a gene product (protein).

- The influenza A genome contains 11 genes on eight pieces of RNA, encoding for 11 proteins: hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA), nucleoprotein (NP), M1, M2, NS1, NS2(NEP: nuclear export protein), PA, PB1 (polymerase basic 1), PB1-F2 and PB2.[5]

- Hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) are the two large glycoproteins on the outside of the viral particles.

- HA is a lectin that mediates binding of the virus to target cells and entry of the viral genome into the target cell, while NA is involved in the release of progeny virus from infected cells, by cleaving sugars that bind the mature viral particles.[6]

- These proteins are targets for antiviral drugs[7] and antigens to which antibodies can be raised.

Tropism

- The viruses attach to cells within the nasal passages and throat in the respiratory tract.

- The influenza virus’s hemagglutinin (HA) surface proteins then bind to the sialic acid receptors on the surface of a human respiratory tract cell.

- The structure of the influenza virus’s HA surface proteins is designed to fit the sialic acid receptors of the human cell, like a key to a lock.

- Once the key enters the lock, the influenza virus is then able to enter and infect the cell. This marks the beginning of a flu infection

Natural Reservoir

| Species | Hemagglutinin Subtypes |

Neuraminidase Subtypes |

|---|---|---|

| Humans | H1, H2, H3, H5, H6, H7, H9, H10 | N1, N2, N6, N7, N8, N9 |

| Poultry | H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7, H8, H9, H10, H11, H12, H13, H14, H15, H16 | N1, N2, N3, N4, N5, N6, N7, N8, N9 |

| Pigs | H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H9 | N1, N2 |

| Bats | H17, H18 | N10, N11 |

| Adapted from CDC [8] | ||

- In nature, the flu virus is found in wild aquatic birds, such as ducks and shore birds.

- It has persisted in these birds for millions of years and does not typically harm them; but the frequently mutating flu viruses can readily jump the species barrier from wild birds to domesticated poultry and swine.

- Pigs can be infected by both bird (avian) flu and the form that infects humans.

- In a setting such as a farm where chickens, pigs, and humans live in close proximity, pigs act as an influenza virus mixing bowl.

- If a pig is infected with avian and human flu simultaneously, the two types of virus may exchange genes.

- Such a "reassorted" flu virus can sometimes spread from pigs to people.

- Depending on the combination of avian flu proteins that make it into the human population, the flu may be more or less severe.

- In 1997, for the first time, scientists found that a form of avian H5N1 flu skipped the pig step and infected humans directly.

- Alarmed health officials feared a worldwide epidemic (a pandemic), but fortunately, the virus could not pass from person to person and thus did not spark an epidemic.

Microscopic Pathology

-

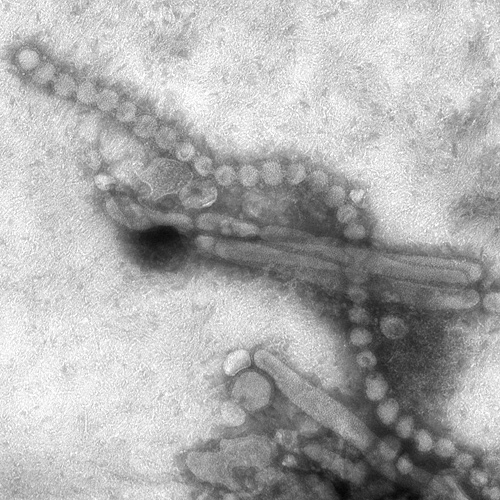

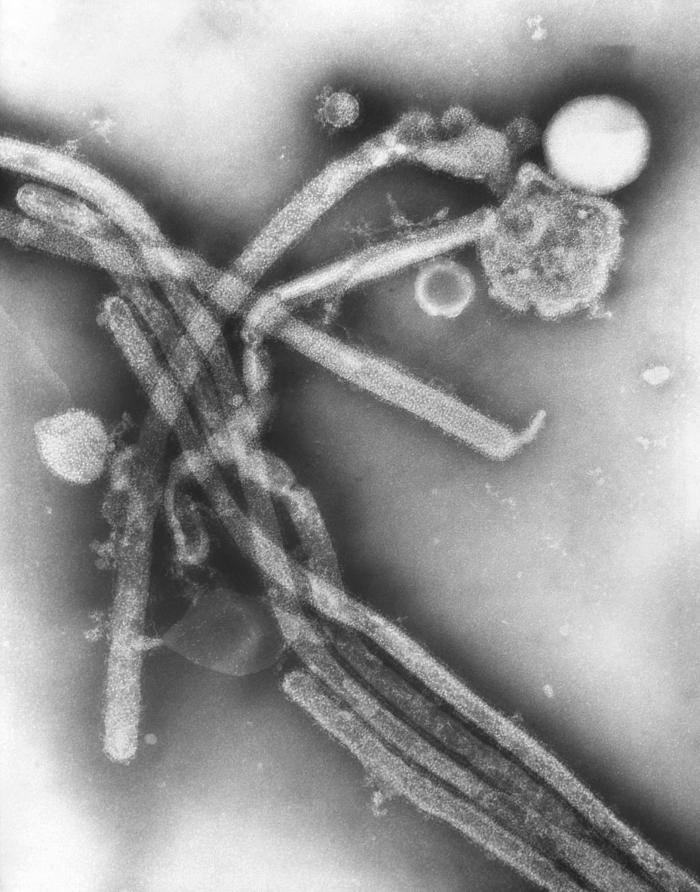

Electron Micrograph Images of H7N9 Virus from China.

Image obtained from CDC. -

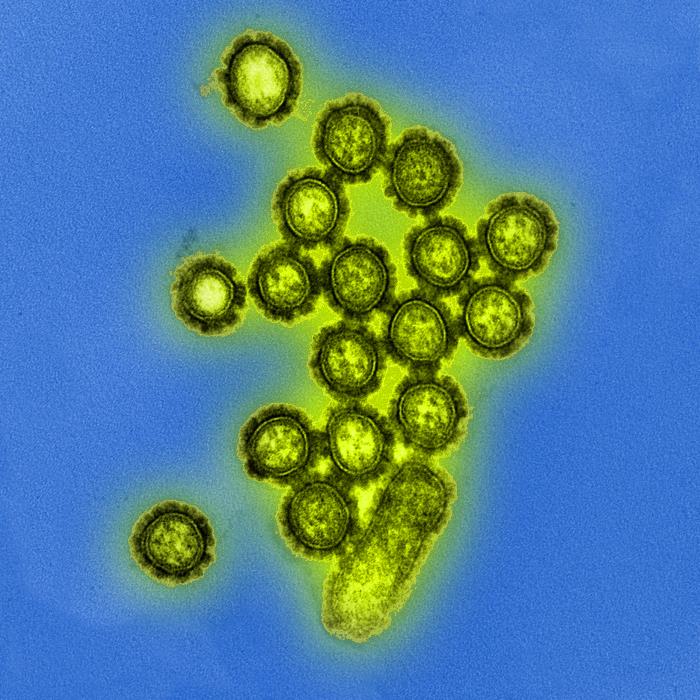

Produced by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), this digitally-colorized transmission electron micrograph (TEM) depicts numbers of H1N1 influenza virus particles. Surface proteins located on the surface of the virus particles are shown in black.

Image obtained from Public Health Image Library (PHIL). -

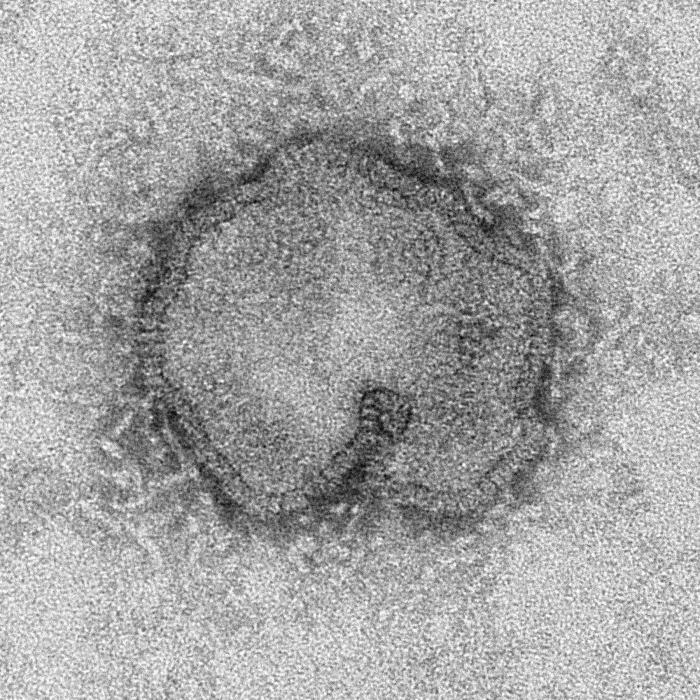

This negatively-stained transmission electron micrograph (TEM) captured some of the ultrastructural details exhibited by the new influenza A (H7N9) virus.

Image obtained from Public Health Image Library (PHIL). -

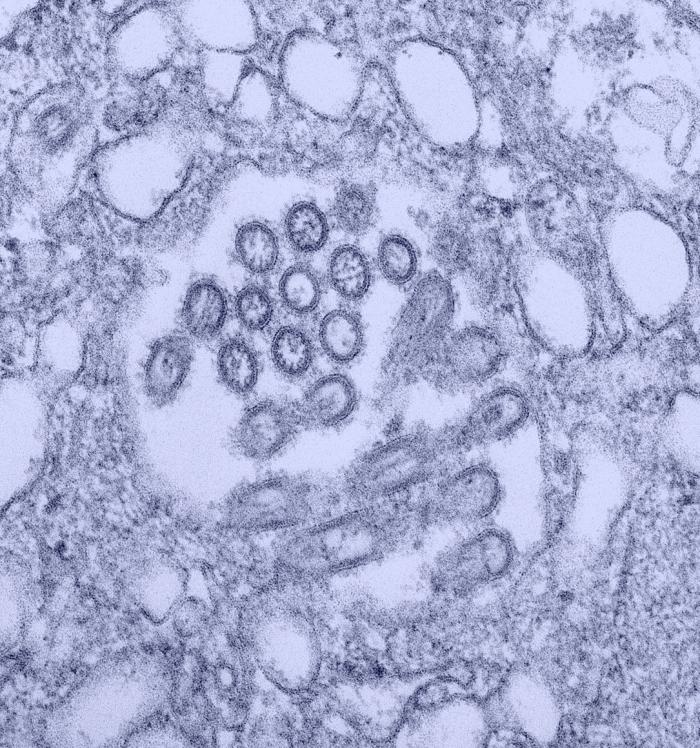

This colorized transmission electron micrograph (TEM) revealed the presence of a number of Novel H1N1 virus virions in this tissue culture sample.

Image obtained from Public Health Image Library (PHIL). -

This negatively-stained transmission electron micrograph (TEM) revealed the presence of a number of Hong Kong flu virus virions, the H3N2 subtype of the influenza A virus.

Image obtained from Public Health Image Library (PHIL).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 >"Taxonomy browser (Influenzavirus)".

- ↑ "CDC Types of Influenza Viruses".

- ↑ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. "The Universal Virus Database, version 4: Influenza A".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lamb RA, Choppin PW (1983). "The gene structure and replication of influenza virus". Annu. Rev. Biochem. 52: 467–506. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.002343. PMID 6351727.

- ↑ Ghedin, E; Sengamalay, NA; Shumway, M; Zaborsky, J; Feldblyum, T; Subbu, V; Spiro, DJ; Sitz, J; Koo, H (October 2005). "Large-scale sequencing of human influenza reveals the dynamic nature of viral genome evolution". Nature. 437 (7062): 1162–6. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1162G. doi:10.1038/nature04239. PMID 16208317.

- ↑ Suzuki, Y (2005). "Sialobiology of influenza: molecular mechanism of host range variation of influenza viruses". Biol Pharm Bull. 28 (3): 399–408. doi:10.1248/bpb.28.399. PMID 15744059.

- ↑ Wilson, J; von Itzstein M (July 2003). "Recent strategies in the search for new anti-influenza therapies". Curr Drug Targets. 4 (5): 389–408. doi:10.2174/1389450033491019. PMID 12816348.

- ↑ "CDC Seasonal Influenza - Transmission of Influenza Viruses from Animals to People".