Leiomyoma

Template:Leiomyoma For patient information, click here.

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Roukoz A. Karam, M.D.[2]; Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [3]; Shanshan Cen, M.D. [4]; Ammu Susheela, M.D. [5]

Synonyms and keywords: Uterine myoma; Fibroid; Fibroids; Uterine; Fibroid Tumor; Fibroid Uterus; Uterine fibromyoma; Leiomyomata

Overview

Uterine leiomyoma was first discovered by Hippocrates in 460-375 B.C and called it “uterine stone”. Uterine leiomyoma may be classified according to their location into 3 subtypes: submucosal, subserous, and intramural. The pathogenesis of leiomyoma is characterized by benign smooth muscle neoplasm. They can occur in any organ, but the most common forms occur in the uterus, small bowel and the esophagus. Chromosome aberrations such as t(12;14)(q14-q15;q23–24), del(7)(q22q32), rearrangements involving 6p21, 10q, trisomy 12, and deletions of 1p3q has been associated with the development of leiomyoma. Uterine leiomyoma must be differentiated from other diseases that cause uterine mass, such as: uterine adenomyoma, pregnancy, hematometra, uterine sarcoma, uterine carcinosarcoma, and metastasis. Leiomyoma is more commonly observed among patients aged 40 years and older. Common risk factors in the development of uterine leiomyoma include African-American race, early menarche, prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol, having one or more pregnancies extending beyond 20 weeks, obesity, significant consumption of beef and other reds meats, hypertension, family history, and alcohol consumption. Physical examination may be remarkable for enlarged, mobile uterus with an irregular contour on bimanual pelvic examination. The mainstay of therapy for uterine leiomyoma is oral contraceptive pills, either combination pills or progestin-only, Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs. Surgery is also part of mainstay therapy for uterine leiomyoma.

Historical Perspective

- Uterine leiomyoma was first discovered by Hippocrates, an ancient Greek physician, in 460-375 B.C and called it “uterine stone”.

- In the second century AD, Galen described the lesion as "scleromas".

- In 1860 and 1863, Rokitansky and Klob coined the term fibroid.

- In 1854, Virchow, a German pathologist, demonstrated that those tumors originated from the uterine smooth muscle.

- In 1809, the first laparotomy was conducted by Ephraim McDowell to treat leiomyoma in Danville, USA.[1]

Classification

- Uterine leiomyoma may be classified according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification system, based on their location in the uterus, into 8 subtypes:[2]

- Intramural myomas

- FIGO types 3, 4, and 5

- Located within the uterine wall

- Submucosal myomas

- Derived from myometrial cells below the endometrium and may protrude into the uterine cavity

- May be subclassified according to this protrusion:

- Type 0: pedunculated intracavitary

- Type 1: < 50% intramural

- Type 2: ≥ 50% itramural

- Subserosal myomas

- FIGO types 6 and 7

- Derived from myometrium at the at the serous surface of the uterus

- Cervical myomas

- FIGO type 8

- Usually located in the cervix

- Intramural myomas

Pathophysiology

- The pathogenesis of leiomyoma is characterized by benign smooth muscle neoplasm. They can occur in any organ, but the most common forms occur in the uterus, small bowel and the esophagus.

- It is thought that leiomyoma is the result of either transformation of normal uterine muscle cells into abnormal cells through somatic mutations, or through the growth of abnormal uterine muscle cells into tumors.[3][4]

- Genetic mutations involved in the pathogenesis of leiomyoma include: [5]

- t(12;14)(q14-q15;q23–24)

- del(7)(q22q32)

- Rearrangements involving 6p21, 10q, trisomy 12

- Deletions of 1p3q

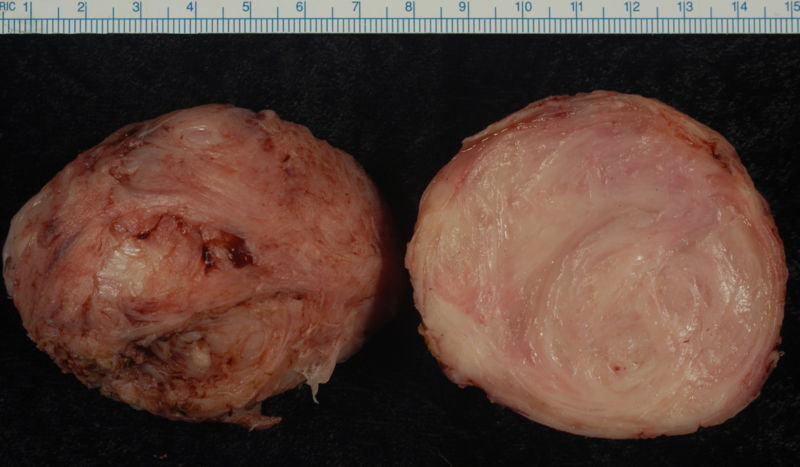

- On gross pathology, round, well circumscribed, non-encapsulated, solid white or tan nodules, and whorled are characteristic findings of leiomyoma.[6]

- On microscopic histopathological analysis, elongated and spindle-shaped cells with a cigar-shaped nucleus are characteristic findings of leiomyoma.

-

Leiomyoma enucleated from a uterus. External surface on left; cut surface on right

-

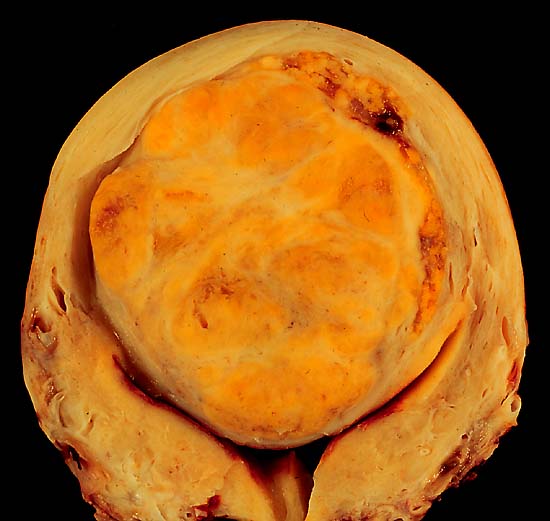

A large, solitary leiomyoma in the uterus, distoring the endometrial cavity into a Y shape by splaying and pressing it downwards.

(Image courtesy of Ed Uthman, MD)

Causes

- Chromosome aberrations such as t(12;14)(q14-q15;q23–24), del(7)(q22q32), rearrangements involving 6p21, 10q, trisomy 12, and deletions of 1p3q have been associated with the development of leiomyoma.[5]

Differentiating Leiomyoma from other Diseases

Leiomyoma is a cause of abnormal uterine bleeding and can result in infertility. There are several diseases which can result in excessive uterine bleeding and the following table is a description of various causes of excessive uterine bleeding.

| Clinical Features | Physical Examination | Diagnostic Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endometriosis |

|

|

|

| Adenomyosis[7] |

|

|

|

| Submucous uterine leiomyomas[8] |

|

|

|

| Pelvic Inflammatory disease[9] |

|

|

|

| Pelvic congestion Syndrome[10] |

|

|

|

Epidemiology and Demographics

Age

- Leiomyoma commonly affects individuals between menarche and menopause.

- The incidence increases with age during reproductive years.[11]

Race

- Leiomyoma usually affects African-American women.[11]

- Incidence rates are approximately threefold greater in African-American women than in white women.

Risk Factors

- Common risk factors in the development of uterine leiomyoma include:[11][12][13][14][15][16][17]

- African-American race

- Early menarche

- Prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol

- Parity

- Having one or more pregnancies extending beyond 20 weeks

- Obesity

- Diet

- Significant consumption of beef and other reds meats

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Alcohol consumption

- Smoking

- Hormonal contraception

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

- The majority of patients with uterine leiomyoma remain asymptomatic for a long time; they are usually found incidentally on imaging or examined after patients start having symptoms.

- Studies have shown that 7 to 40% of premenopausal patients with leiomyoma may witness regression of fibroids over 6 months to 3 years.[18]

- At menopause most fibroids will start to shrink as menstrual cycles stop and hormone levels wane.[18]

- Common complications of uterine leiomyoma include:[19][20][21]

- Dysmenorrhea

- Dyspareunia

- Leiomyoma degeneration or torsion

- Transcervical prolapse

- Miscarriage

- Less common complications of uterine leiomyoma include:[22][23][24]

- Venous compression

- Polycythemia from autonomous production of erythropoietin

- Hypercalcemia from autonomous production of parathyroid hormone-related protein

- Hyperprolactinemia

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Study of Choice

- The diagnosis of uterine leiomyoma is based on a clinical diagnosis, which includes a pelvic exam and pelvic ultrasound finding of leiomyomas.

- A pelvic ultrasound is indicated when patients suffer from symptoms of leiomyoma.

- A biopsy is usually not needed to make the diagnosis, but should be performed if clinician is suspicious that the mass is not a fibroid.[25]

Symptoms

- The majority of patients with leiomyoma are usually asymptomatic.

- Symptoms of uterine leiomyoma may include the following:[26]

- Abnormal uterine bleeding

- Heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding

- Painful sexual intercourse

- Abdominal discomfort or bloating

- Back pain

- Urinary frequency

- Urinary retention

- Constipation

- Infertility

Physical Examination

- Common physical examination findings of uterine leiomyoma include enlarged, mobile uterus with an irregular contour on bimanual pelvic examination.[26]

Imaging Findings

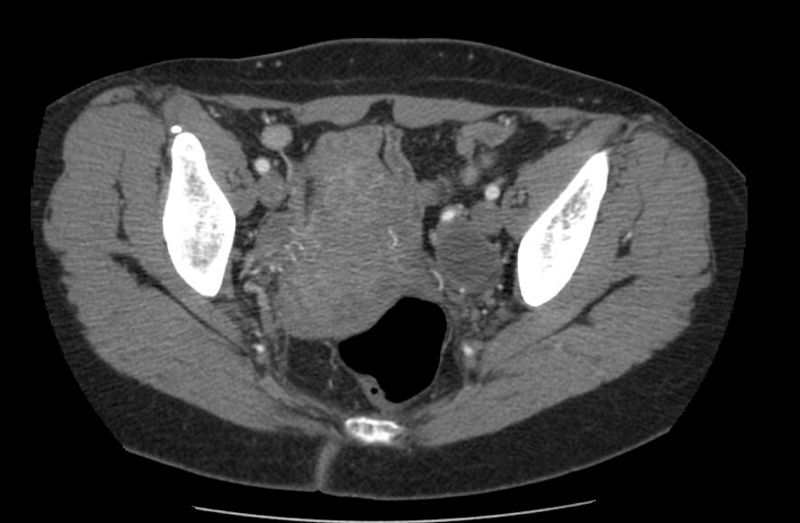

- Pelvic ultrasound is helpful in the diagnosis of uterine leiomyoma.

- Findings on an ultrasound diagnostic of uterine leiomyoma include fibroids as focal masses with a heterogeneous texture, which usually cause shadowing of the ultrasound beam.[27]

Other Diagnostic Studies

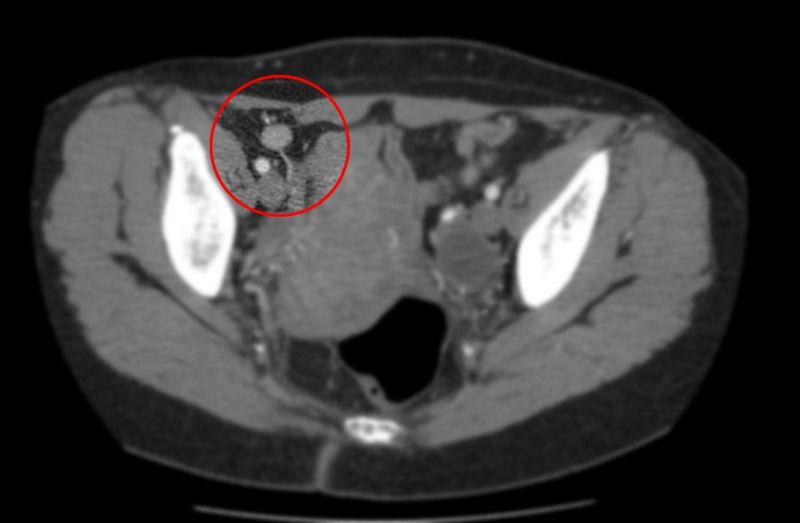

- Uterine leiomyoma may also be diagnosed using diagnostic hysteroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, and hysterosalpingography.

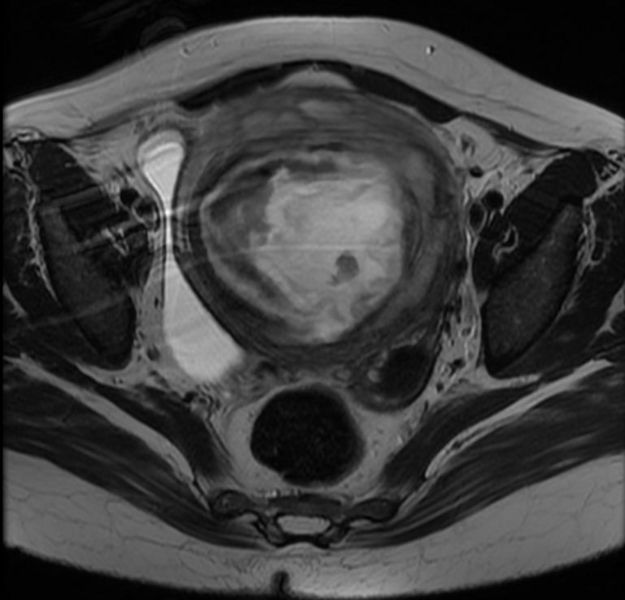

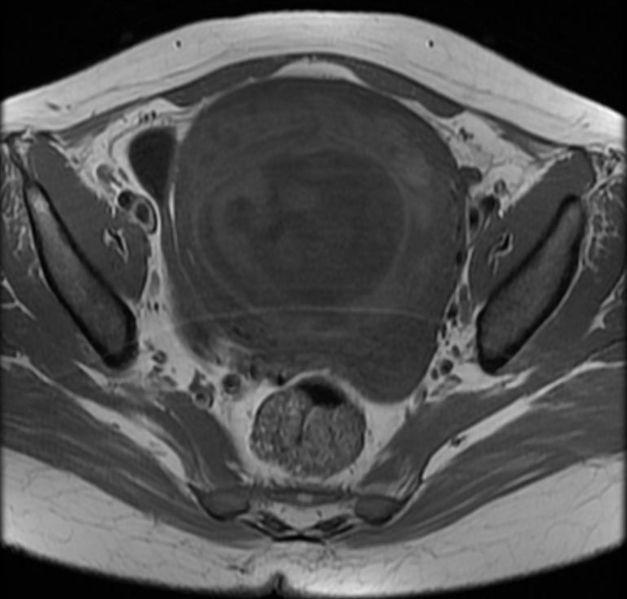

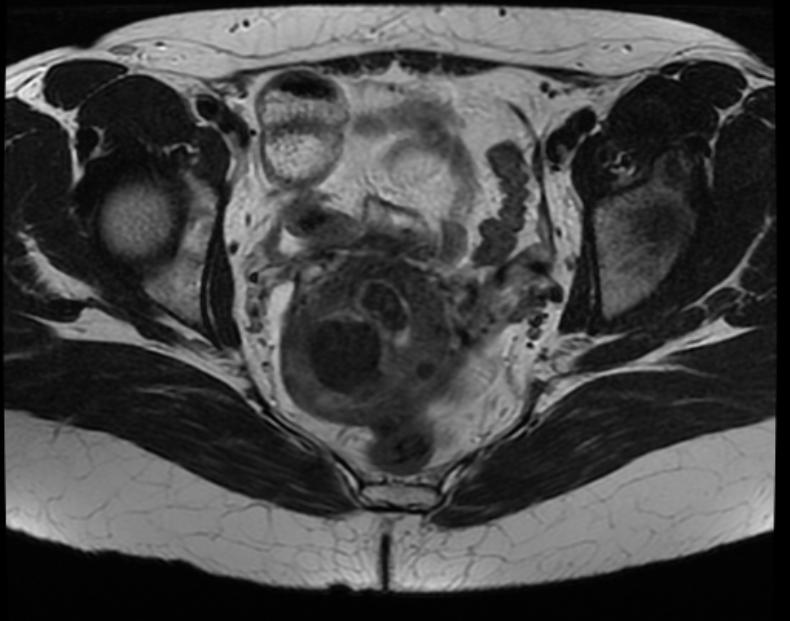

Patient #1: MR images demonstrate large degenerating leiomyomas

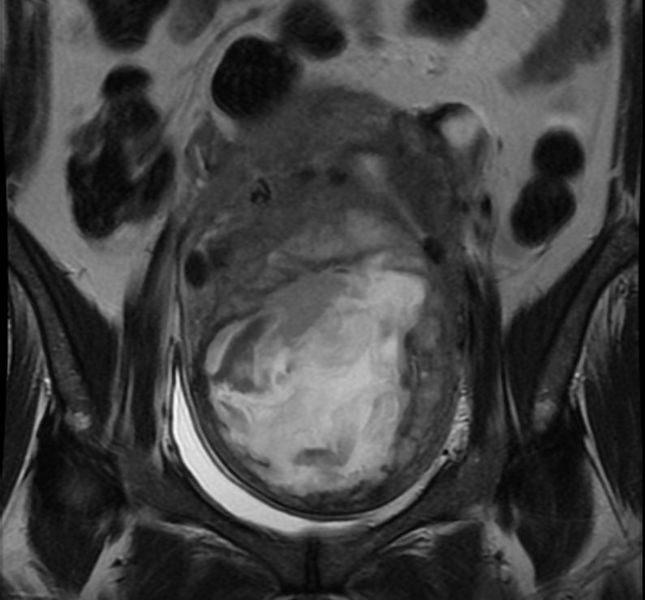

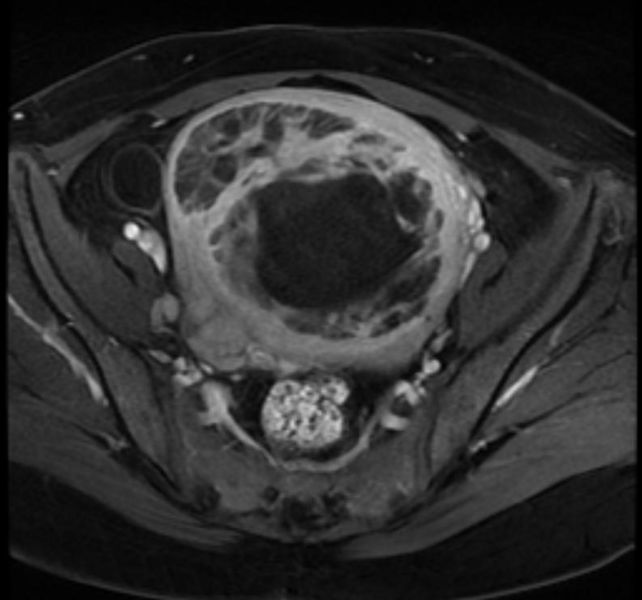

Patient #2: MR images demonstrate a leiomyoma prolapsing into the endometrial canal

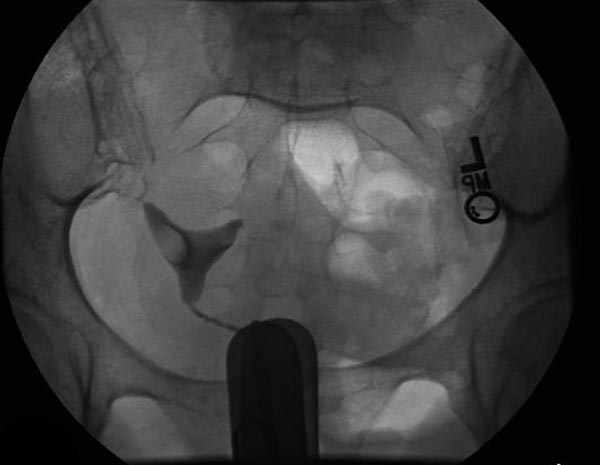

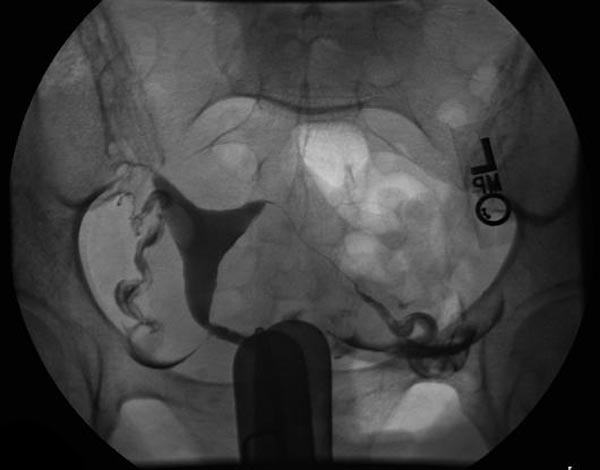

Hysterosalpingogram(HSG) reveals a submucosal leiomyoma

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- Uterine leiomyomas usually shrink and regress during menopause and the postpartum period.

- Literature is lacking concerning the medical therapy for leiomyoma, and due to their self-limited nature, expectant management is considered in some cases.[28][29]

- Pharmacologic medical therapy in the form of oral contraceptives is recommended among premenopausal patients with mild symtpoms and mildly enlarged uteri.[30]

- Pharmacologic medical therapies for leiomyoma include:[31][32][33][34]

- Estrogen-progestin contraceptives

- Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

- Progestin implants, injections, and pills

- Progesterone receptor modulators

- Ulipristal acetate

- Mifepristone

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Danazol and gestrinone

Surgery

- Surgery is the mainstay of therapy for uterine leiomyoma.

- Uterine artery embolization in conjunction with laparotomic myomectomy is the most common approach to the treatment of leiomyoma.

- Hysteroscopic myomectomy can also be performed for patients with uterine leiomyoma.[35]

- Surical indications for surgical therapy include following:

- Abnormal uterine bleeding or bulk-related symptoms

- Infertility or recurrent pregnancy loss

References

- ↑ Bozini, Nilo; Baracat, Edmund C (2007). "The history of myomectomy at the Medical School of University of São Paulo". Clinics. 62 (3). doi:10.1590/S1807-59322007000300002. ISSN 1807-5932.

- ↑ Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS, FIGO Menstrual Disorders Working Group (2011). "The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years". Fertil Steril. 95 (7): 2204–8, 2208.e1–3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.079. PMID 21496802.

- ↑ Hashimoto K, Azuma C, Kamiura S, Kimura T, Nobunaga T, Kanai T; et al. (1995). "Clonal determination of uterine leiomyomas by analyzing differential inactivation of the X-chromosome-linked phosphoglycerokinase gene". Gynecol Obstet Invest. 40 (3): 204–8. doi:10.1159/000292336. PMID 8529956.

- ↑ Mashal RD, Fejzo ML, Friedman AJ, Mitchner N, Nowak RA, Rein MS; et al. (1994). "Analysis of androgen receptor DNA reveals the independent clonal origins of uterine leiomyomata and the secondary nature of cytogenetic aberrations in the development of leiomyomata". Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 11 (1): 1–6. PMID 7529041.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Genetics of Uterine Leiomyomas. glowm (2016). http://www.glowm.com/section_view/heading/Genetics%20of%20Uterine%20Leiomyomas/item/363 Accessed on April 19, 2016

- ↑ Zhu X, Fei J, Zhang W, Zhou J (2015). "Uterine leiomyoma mimicking a gastrointestinal stromal tumor with chronic spontaneous hemorrhage: A case report". Oncol Lett. 9 (6): 2481–2484. doi:10.3892/ol.2015.3083. PMC 4473300. PMID 26137094.

- ↑ Parker JD, Leondires M, Sinaii N, Premkumar A, Nieman LK, Stratton P (2006). "Persistence of dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pain after optimal endometriosis surgery may indicate adenomyosis". Fertil Steril. 86 (3): 711–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.030. PMID 16782099.

- ↑ Donnez J, Donnez O, Matule D, Ahrendt HJ, Hudecek R, Zatik J; et al. (2016). "Long-term medical management of uterine fibroids with ulipristal acetate". Fertil Steril. 105 (1): 165–173.e4. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.032. PMID 26477496.

- ↑ Ross J, Judlin P, Jensen J, International Union against sexually transmitted infections (2014). "2012 European guideline for the management of pelvic inflammatory disease". Int J STD AIDS. 25 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1177/0956462413498714. PMID 24216035.

- ↑ Rozenblit AM, Ricci ZJ, Tuvia J, Amis ES (2001). "Incompetent and dilated ovarian veins: a common CT finding in asymptomatic parous women". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 176 (1): 119–22. doi:10.2214/ajr.176.1.1760119. PMID 11133549.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM (2003). "High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 188 (1): 100–7. PMID 12548202.

- ↑ Dragomir AD, Schroeder JC, Connolly A, Kupper LL, Hill MC, Olshan AF; et al. (2010). "Potential risk factors associated with subtypes of uterine leiomyomata". Reprod Sci. 17 (11): 1029–35. doi:10.1177/1933719110376979. PMID 20693498.

- ↑ Baird DD, Newbold R (2005). "Prenatal diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure is associated with uterine leiomyoma development". Reprod Toxicol. 20 (1): 81–4. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.01.002. PMID 15808789.

- ↑ Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Goldman MB, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Barbieri RL; et al. (1998). "A prospective study of reproductive factors and oral contraceptive use in relation to the risk of uterine leiomyomata". Fertil Steril. 70 (3): 432–9. PMID 9757871.

- ↑ Sato F, Nishi M, Kudo R, Miyake H (1998). "Body fat distribution and uterine leiomyomas". J Epidemiol. 8 (3): 176–80. PMID 9782674.

- ↑ Chiaffarino F, Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, Chatenoud L, Di Cintio E, Marsico S (1999). "Diet and uterine myomas". Obstet Gynecol. 94 (3): 395–8. PMID 10472866.

- ↑ Wise LA, Palmer JR, Harlow BL, Spiegelman D, Stewart EA, Adams-Campbell LL; et al. (2004). "Risk of uterine leiomyomata in relation to tobacco, alcohol and caffeine consumption in the Black Women's Health Study". Hum Reprod. 19 (8): 1746–54. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh309. PMC 1876785. PMID 15218005.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 DeWaay DJ, Syrop CH, Nygaard IE, Davis WA, Van Voorhis BJ (2002). "Natural history of uterine polyps and leiomyomata". Obstet Gynecol. 100 (1): 3–7. PMID 12100797.

- ↑ Gupta, Sahana; Manyonda, Isaac T. (2009). "Acute complications of fibroids". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 23 (5): 609–617. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.01.012. ISSN 1521-6934.

- ↑ Cordiano V (March 2005). "Complete remission of hyperprolactinemia and erythrocytosis after hysterectomy for a uterine fibroid in a woman with a previous diagnosis of prolactin-secreting pituitary microadenoma". Ann. Hematol. 84 (3): 200–2. doi:10.1007/s00277-004-0973-5. PMID 15599545.

- ↑ Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL (April 2009). "Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence". Fertil. Steril. 91 (4): 1215–23. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.051. PMID 18339376.

- ↑ Ferrero S, Abbamonte LH, Giordano M, Parisi M, Ragni N, Remorgida V (November 2006). "Uterine myomas, dyspareunia, and sexual function". Fertil. Steril. 86 (5): 1504–10. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.04.025. PMID 17070199.

- ↑ Lippman SA, Warner M, Samuels S, Olive D, Vercellini P, Eskenazi B (December 2003). "Uterine fibroids and gynecologic pain symptoms in a population-based study". Fertil. Steril. 80 (6): 1488–94. PMID 14667888.

- ↑ Fletcher H, Wharfe G, Williams NP, Gordon-Strachan G, Pedican M, Brooks A (November 2009). "Venous thromboembolism as a complication of uterine fibroids: a retrospective descriptive study". J Obstet Gynaecol. 29 (8): 732–6. doi:10.3109/01443610903165545. PMID 19821668.

- ↑ Buttram VC, Reiter RC (1981). "Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management". Fertil Steril. 36 (4): 433–45. PMID 7026295.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Buttram VC, Reiter RC (1981). "Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management". Fertil Steril. 36 (4): 433–45. PMID 7026295.

- ↑ Wilde S, Scott-Barrett S (2009). "Radiological appearances of uterine fibroids". Indian J Radiol Imaging. 19 (3): 222–31. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.54887. PMC 2766886. PMID 19881092.

- ↑ Viswanathan M, Hartmann K, McKoy N, Stuart G, Rankins N, Thieda P; et al. (2007). "Management of uterine fibroids: an update of the evidence". Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) (154): 1–122. PMC 4781116. PMID 18288885.

- ↑ Laughlin SK, Hartmann KE, Baird DD (2011). "Postpartum factors and natural fibroid regression". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 204 (6): 496.e1–6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.018. PMC 3136622. PMID 21492823.

- ↑ Carlson KJ, Miller BA, Fowler FJ (1994). "The Maine Women's Health Study: II. Outcomes of nonsurgical management of leiomyomas, abnormal bleeding, and chronic pelvic pain". Obstet Gynecol. 83 (4): 566–72. PMID 8134067.

- ↑ Donnez J, Tomaszewski J, Vázquez F, Bouchard P, Lemieszczuk B, Baró F, Nouri K, Selvaggi L, Sodowski K, Bestel E, Terrill P, Osterloh I, Loumaye E (February 2012). "Ulipristal acetate versus leuprolide acetate for uterine fibroids". N. Engl. J. Med. 366 (5): 421–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1103180. PMID 22296076.

- ↑ Murji A, Whitaker L, Chow TL, Sobel ML (April 2017). "Selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) for uterine fibroids". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4: CD010770. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010770.pub2. PMID 28444736.

- ↑ Carr BR, Marshburn PB, Weatherall PT, Bradshaw KD, Breslau NA, Byrd W, Roark M, Steinkampf MP (May 1993). "An evaluation of the effect of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs and medroxyprogesterone acetate on uterine leiomyomata volume by magnetic resonance imaging: a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 76 (5): 1217–23. doi:10.1210/jcem.76.5.8496313. PMID 8496313.

- ↑ Starczewski A, Iwanicki M (September 2000). "[Intrauterine therapy with levonorgestrel releasing IUD of women with hypermenorrhea secondary to uterine fibroids]". Ginekol. Pol. (in Polish). 71 (9): 1221–5. PMID 11083008.

- ↑ Borah BJ, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Myers ER, Yao X, Stewart EA (2016). "Association Between Patient Characteristics and Treatment Procedure Among Patients With Uterine Leiomyomas". Obstet Gynecol. 127 (1): 67–77. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001160. PMC 4689646. PMID 26646122.