COVID-19-associated headache

|

COVID-19 Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

COVID-19-associated headache On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of COVID-19-associated headache |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for COVID-19-associated headache |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Fahimeh Shojaei, M.D. Syed Musadiq Ali M.B.B.S.[2]

Synonyms and keywords:

Overview

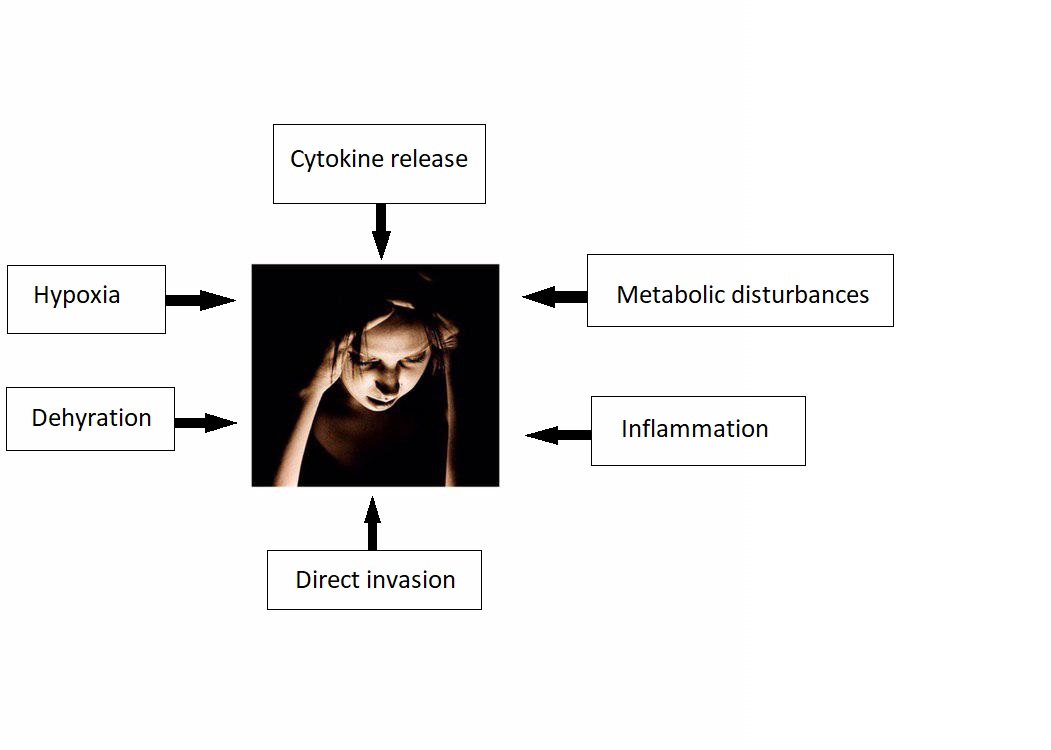

The association between COVID-19 and headache was made in 2020. COVID-19 associated headache may be caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus. There is no established system for the classification of COVID-19 associated headache. The exact pathogenesis of headache in COVID 19 patients is not fully understood. It is thought that headache is the result of cytokine release, direct invasion, metabolic disturbances, inflammation, dehydration, and hypoxia. COVID-19-associated headache must be differentiated from other diseases that cause headache, such as migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache, seizure, meningitis, encephalitis, neurosyphilis, SAH, subdural hematoma, brain tumor, hypertensive encephalopathy, brain abscess, multiple sclerosis, hemorrhagic stroke, Wernickes encephalopathy, and drug toxicity. A positive history of fever and cough in addition to headache is suggestive of COVID-19-associated headache.

Historical Perspective

- The association between COVID-19 and headache was made in December, 2019 during SARS-CoV-2 outbreak initiated in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China.[1]

Classification

- There is no established system for the classification of COVID-19 associated headache.

Pathophysiology

- The exact pathogenesis of headache in COVID 19 patients is not fully understood.

- It is thought that headache is the result of:[2][3][4][5]

- Cytokine release

- There is higher concentration on IL-6 and INF-gamma in patients infected with SARS/ CoV2.

- Cytokines can disrupt blood brain barrier and cause tissue injury and cerebral edema.

- Direct invasion

- Metabolic disturbances

- Inflammation

- Dehydration

- Hypoxia

- Cytokine release

Causes

- COVID-19 associated headache may be caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Differentiating COVID-19-associated headache from other Diseases

COVID-19-associated headache must be differentiated from other diseases that cause headache, such as migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache, seizure, meningitis, encephalitis, neurosyphilis, SAH, subdural hematoma, brain tumor, hypertensive encephalopathy, brain abscess, multiple sclerosis, hemorrhagic stroke, Wernickes encephalopathy, and drug toxicity etc.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]

| Disease | History and Physical Examination | PMHx | Diagnostic approach | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral | Throbbing character | Autonomic symptoms | Fever | Photophobia | Aphasia | LOC | Aura | Nause/

Vomiting |

Rash | Neck stiffness | Vision changes | Neurologic deficits | Labs and CSF findings | CT/MRI | Gold standard test | ||

| Migraine | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | Trigger factors, family hx | - | - | Clinical assesment |

| Tension-type headache (TTH) | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | stress, genetics | - | - | Clinical assesment |

| Cluster headache | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | episodic history | - | - | Clinical assesment |

| Seizure | + | - | - | - | - | +/- | + | +/- | - | - | - | - | +/- | Hx of seizures | prolactin level | +/- mass lesion | EEG [25] |

| Meningitis | + | - | - | + | +/- | +/- | - | - | +/- | +/- | + | - | + | Hx of fever, malaise | <math>\uparrow</math>WBC

<math>\uparrow</math>Protein <math>\downarrow</math>glucose |

+/- | CSF analysis[26] |

| Encephalitis | + | +/- | - | + | +/- | +/- | - | - | - | +/- | + | - | + | Hx of fever, malaise | elevated WBC, low glucose | + | CSF PCR |

| Brain tumor[27] | + | - | - | - | - | +/- | - | - | +/- | - | - | +/- | +/- | weight loss, fatigue | neuromarkers,

Cancer cells[28] |

+/- mass | MRI |

| Subdural hemorrhage | -/+ | +/- | - | - | - | +/- | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | +/- | Trauma, fall | Xanthochromia | + | CT w/o contrast |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | -/+ | +/- | - | - | +/- | +/- | - | - | - | - | +/- | +/- | +/- | thunderclap headache | <math>\uparrow</math>opening pressure, xanthochromia | + | CT w/o contrast |

| Hypertensive encephalopathy | + | +/- | - | - | +/- | - | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | - | Hypertension | UA +/- | +/- | clinical assessment |

| CNS abscess | -/+ | - | - | + | - | +/- | - | - | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | History of drug abuse, endocarditis, immunosupression | ↑ leukocytes, ↓ glucose and ↑ protien | + | MRI |

| Conversion disorder | -/+ | - | - | - | - | +/- | - | - | - | - | +/- | +/- | +/- | History of emotional stress | - | - | Diagnosis of exclusion |

| Multiple sclerosis | -/+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | +/- | History of relapses and remissions | ↑ CSF IgG levels

(monoclonal bands) |

+ | MRI |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | -/+ | +/- | - | - | - | +/- | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | +/- | HTN | - | + | CT scan without contrast[29][30] |

| Neurosyphilis[31][32] | -/+ | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | - | - | +/- | - | +/- | +/- | STIs | ↑ Leukocytes and protein | + | CSF VDRL-specifc

CSF FTA-Ab -sensitive[33] |

| Wernicke’s encephalopathy | -/+ | - | - | - | - | +/- | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | +/- | History of alcohal abuse | blood ethanol levels | +/- | Clinical assesment and lab findings |

| Drug toxicity | -/+ | - | - | +/- | - | - | +/- | - | +/- | - | +/- | +/- | +/- | Medication hx | Drug levels | - | Drug screen test |

| Metabolic disturbances | -/+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | - | - | +/- | +/- | Underlying CKD, CLD | Hypoglycemia, hypo and hypernatremia, hypo and hyperkalemia | - | Cause dependent |

| Sinusitis | -/+ | - | - | +/- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | allergies, seasonal | leukocytosis | + | CT |

Epidemiology and Demographics

Incidence / Prevalence

- WHO reported that more than 462,801 people have been infected worldwide, more than 380,723 of which are outside of China.[34]

- The incidence/prevalence of COVID-19-associated headache is still unknown.

- Guan et al. recently reported 13 percent of COVID-19-associated headache among 1099 laboratory-confirmed cases.

Age

- There is insufficient information regarding age-specific prevalence or incidence of COVID-19-associated headache.

Gender

- There is insufficient information regarding gender-specific prevalence or incidence of COVID-19-associated headache.

Race

- There is insufficient information regarding race-specific prevalence or incidence of COVID-19-associated headache.

Risk Factors

- There are no established risk factors for COVID-19-associated headache.

Screening

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis

Natural History

- At this point natural history of COVID-19-associated headache is unknown.

- Further studies are needed to better understand the COVID-19-associated headache.

Complication

- Patients with a history migraine may experience headache as their first symptom, these patients experience more severe headache and are more disabled by the infection compared with age‐matched cohorts.

- Further studies are needed to better understand complication.

- Larger retrospective studies are needed for evaluating the experience of COVID‐19 in patients with a history of a primary headache disorder.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic Study of Choice

- There are no established criteria for the diagnosis of COVID-19-associated headache.

History and Symptoms

- The hallmark of COVID-19-associated headache is headache.

- A positive history of fever and cough in addition to headache is suggestive of COVID-19-associated headache.

Physical Examination

- Patients with COVID-19-associated headache usually appear normal.

- Physical examination of patients with COVID-19-associated headache is usually remarkable for fever, cough, and malaise.

Laboratory Findings

- Additional diagnostic tests like blood chemistry and urine analysis may be needed to rule out other medical conditions.

- There are no diagnostic laboratory findings associated with COVID-19-associated headache.

Electrocardiogram

X-ray

Echocardiography or Ultrasound

- There are no echocardiography/ultrasound findings associated with COVID-19-associated headache.

CT scan

- There are no CT scan findings associated with COVID-19-associated headache.

MRI

- There are no MRI findings associated with COVID-19-associated headache.

Other Imaging Findings

- There are no other imaging findings associated with COVID-19-associated headache.

Other Diagnostic Studies

- There are no other diagnostic studies associated with COVID-19-associated headache.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

- Medical therapy for COVID-assocaited-headache is still controversial[35].

- The use of NSAIDs, who received treatment early in the disease causes worsening of COVID-19 symptoms according to some anecdotal evidences.

- In March 11, 2020, Fang et al. reported the hypothesis that ibuprofen (40 mg/kg/dose)[36] can increase the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19 since ibuprofen is known to upregulate ACE2 receptors[37].

- In March 23, 2020, US FDA announced that it is not aware of any evidence that NSAIDs such as ibuprofen could worsen COVID-19[38].

- The European Medicines Agency and World Health Organization (WHO) have not yet recommended that NSAIDs be avoided.

- Despite this recommendation, as a precautionary measure many providers are avoiding NSAIDs in patients with COVID-19.

- In practice, the decision to continue or stop NSAIDs in patients with COVID-19 is made in collaboration between the treating physician and the patient, after a brief discussion on the limited available evidence.

- More data are needed before broad recommendations are made.

Surgery

Primary Prevention

- There are no established measures for the primary prevention of COVID-19 associated headache.

Secondary Prevention

- There are no established measures for the secondary prevention of COVID-19-associated headache.

References

- ↑ Meng X, Deng Y, Dai Z, Meng Z (June 2020). "COVID-19 and anosmia: A review based on up-to-date knowledge". Am J Otolaryngol. 41 (5): 102581. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102581. PMC 7265845 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32563019 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Baig, Abdul Mannan; Khaleeq, Areeba; Ali, Usman; Syeda, Hira (2020). "Evidence of the COVID-19 Virus Targeting the CNS: Tissue Distribution, Host–Virus Interaction, and Proposed Neurotropic Mechanisms". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 11 (7): 995–998. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122. ISSN 1948-7193.

- ↑ St-Jean JR, Jacomy H, Desforges M, Vabret A, Freymuth F, Talbot PJ (August 2004). "Human respiratory coronavirus OC43: genetic stability and neuroinvasion". J. Virol. 78 (16): 8824–34. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.16.8824-8834.2004. PMC 479063. PMID 15280490.

- ↑ Rossi, Andrea (2008). "Imaging of Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis". Neuroimaging Clinics of North America. 18 (1): 149–161. doi:10.1016/j.nic.2007.12.007. ISSN 1052-5149.

- ↑ St-Jean, Julien R.; Jacomy, Hélène; Desforges, Marc; Vabret, Astrid; Freymuth, François; Talbot, Pierre J. (2004). "Human Respiratory Coronavirus OC43: Genetic Stability and Neuroinvasion". Journal of Virology. 78 (16): 8824–8834. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.16.8824-8834.2004. ISSN 0022-538X.

- ↑ "National guidelines for analysis of cerebrospinal fluid for bilirubin in suspected subarachnoid haemorrhage". Ann. Clin. Biochem. 40 (Pt 5): 481–8. September 2003. doi:10.1258/000456303322326399. PMID 14503985.

- ↑ Le Rhun E, Taillibert S, Chamberlain MC (2013). "Carcinomatous meningitis: Leptomeningeal metastases in solid tumors". Surg Neurol Int. 4 (Suppl 4): S265–88. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.111304. PMC 3656567. PMID 23717798.

- ↑ Chow E, Troy SB (2014). "The differential diagnosis of hypoglycorrhachia in adult patients". Am J Med Sci. 348 (3): 186–90. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000217. PMC 4065645. PMID 24326618.

- ↑ Leen WG, Willemsen MA, Wevers RA, Verbeek MM (2012). "Cerebrospinal fluid glucose and lactate: age-specific reference values and implications for clinical practice". PLoS One. 7 (8): e42745. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042745. PMC 3412827. PMID 22880096.

- ↑ Negrini B, Kelleher KJ, Wald ER (2000). "Cerebrospinal fluid findings in aseptic versus bacterial meningitis". Pediatrics. 105 (2): 316–9. PMID 10654948.

- ↑ Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR, van de Beek D (2010). "Epidemiology, diagnosis, and antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial meningitis". Clin Microbiol Rev. 23 (3): 467–92. doi:10.1128/CMR.00070-09. PMC 2901656. PMID 20610819.

- ↑ Vermeulen M, Hasan D, Blijenberg BG, Hijdra A, van Gijn J (July 1989). "Xanthochromia after subarachnoid haemorrhage needs no revisitation". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 52 (7): 826–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.52.7.826. PMC 1031927. PMID 2769274.

- ↑ Wasay M, Mekan SF, Khelaeni B, Saeed Z, Hassan A, Cheema Z, Bakshi R (June 2005). "Extra temporal involvement in herpes simplex encephalitis". Eur. J. Neurol. 12 (6): 475–9. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.00999.x. PMID 15885053.

- ↑ Glaser CA, Honarmand S, Anderson LJ, Schnurr DP, Forghani B, Cossen CK, Schuster FL, Christie LJ, Tureen JH (December 2006). "Beyond viruses: clinical profiles and etiologies associated with encephalitis". Clin. Infect. Dis. 43 (12): 1565–77. doi:10.1086/509330. PMID 17109290.

- ↑ Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL (May 2011). "Rhinosinusitis diagnosis and management for the clinician: a synopsis of recent consensus guidelines". Mayo Clin. Proc. 86 (5): 427–43. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0392. PMC 3084646. PMID 21490181.

- ↑ Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, Olesen J (1991). "Epidemiology of headache in a general population--a prevalence study". J Clin Epidemiol. 44 (11): 1147–57. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(91)90147-2. PMID 1941010.

- ↑ Kelman L (October 2004). "The premonitory symptoms (prodrome): a tertiary care study of 893 migraineurs". Headache. 44 (9): 865–72. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04168.x. PMID 15447695.

- ↑ Laurell K, Artto V, Bendtsen L, Hagen K, Häggström J, Linde M, Söderström L, Tronvik E, Wessman M, Zwart JA, Kallela M (September 2016). "Premonitory symptoms in migraine: A cross-sectional study in 2714 persons". Cephalalgia. 36 (10): 951–9. doi:10.1177/0333102415620251. PMID 26643378.

- ↑ Charlotte E. Grayson and The Cleveland Clinic Neuroscience Center (October 2004). "Cluster Headaches". WebMD. Retrieved 2006-09-22.

- ↑ Drummond PD (October 1994). "Sweating and vascular responses in the face: normal regulation and dysfunction in migraine, cluster headache and harlequin syndrome". Clin. Auton. Res. 4 (5): 273–85. doi:10.1007/BF01827433. PMID 7888747.

- ↑ Drummond PD (June 2006). "Mechanisms of autonomic disturbance in the face during and between attacks of cluster headache". Cephalalgia. 26 (6): 633–41. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01106.x. PMID 16686902.

- ↑ Ekbom K (August 1990). "Evaluation of clinical criteria for cluster headache with special reference to the classification of the International Headache Society". Cephalalgia. 10 (4): 195–7. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1990.1004195.x. PMID 2245469.

- ↑ Sandrini G, Antonaci F, Pucci E, Bono G, Nappi G (December 1994). "Comparative study with EMG, pressure algometry and manual palpation in tension-type headache and migraine". Cephalalgia. 14 (6): 451–7, discussion 394–5. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1994.1406451.x. PMID 7697707.

- ↑ Jensen R, Fuglsang-Frederiksen A (June 1994). "Quantitative surface EMG of pericranial muscles. Relation to age and sex in a general population". Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 93 (3): 175–83. doi:10.1016/0168-5597(94)90038-8. PMID 7515793.

- ↑ Manford M (2001). "Assessment and investigation of possible epileptic seizures". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 70 Suppl 2: II3–8. PMC 1765557. PMID 11385043.

- ↑ Carbonnelle E (2009). "[Laboratory diagnosis of bacterial meningitis: usefulness of various tests for the determination of the etiological agent]". Med Mal Infect. 39 (7–8): 581–605. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2009.02.017. PMID 19398286.

- ↑ Morgenstern LB, Frankowski RF (1999). "Brain tumor masquerading as stroke". J Neurooncol. 44 (1): 47–52. PMID 10582668.

- ↑ Weston CL, Glantz MJ, Connor JR (2011). "Detection of cancer cells in the cerebrospinal fluid: current methods and future directions". Fluids Barriers CNS. 8 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/2045-8118-8-14. PMC 3059292. PMID 21371327.

- ↑ Birenbaum D, Bancroft LW, Felsberg GJ (2011). "Imaging in acute stroke". West J Emerg Med. 12 (1): 67–76. PMC 3088377. PMID 21694755.

- ↑ DeLaPaz RL, Wippold FJ, Cornelius RS, Amin-Hanjani S, Angtuaco EJ, Broderick DF; et al. (2011). "ACR Appropriateness Criteria® on cerebrovascular disease". J Am Coll Radiol. 8 (8): 532–8. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.05.010. PMID 21807345.

- ↑ Liu LL, Zheng WH, Tong ML, Liu GL, Zhang HL, Fu ZG; et al. (2012). "Ischemic stroke as a primary symptom of neurosyphilis among HIV-negative emergency patients". J Neurol Sci. 317 (1–2): 35–9. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2012.03.003. PMID 22482824.

- ↑ Berger JR, Dean D (2014). "Neurosyphilis". Handb Clin Neurol. 121: 1461–72. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-4088-7.00098-5. PMID 24365430.

- ↑ Ho EL, Marra CM (2012). "Treponemal tests for neurosyphilis--less accurate than what we thought?". Sex Transm Dis. 39 (4): 298–9. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31824ee574. PMC 3746559. PMID 22421697.

- ↑ Tu H, Tu S, Gao S, Shao A, Sheng J (2020). "Current epidemiological and clinical features of COVID-19; a global perspective from China". J Infect. 81 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.011. PMC 7166041 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32315723 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Zhang J, Xie B, Hashimoto K (2020). "Current status of potential therapeutic candidates for the COVID-19 crisis". Brain Behav Immun. 87: 59–73. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.046. PMC 7175848 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32334062 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ MaassenVanDenBrink A, de Vries T, Danser A (April 2020). "Headache medication and the COVID-19 pandemic". J Headache Pain. 21 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s10194-020-01106-5. PMC 7183387 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32334535 Check|pmid=value (help). Vancouver style error: initials (help) - ↑ Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M (2020) Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 8 (4):e21. DOI:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8 PMID: 32171062

- ↑ FitzGerald GA (2020) Misguided drug advice for COVID-19. Science 367 (6485):1434. DOI:10.1126/science.abb8034 PMID: 32198292