Alzheimer's disease

Template:DiseaseDisorder infobox

|

Alzheimer's disease Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Alzheimer's disease On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Alzheimer's disease |

For patient information click here

Editor(s)-in-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S.,M.D. [1] Phone:617-632-7753; Peter Pressman, M.D. [2], Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Department of Neurology

Dr. Pressman has nothing to disclose.

Synonyms and keywords: AD; Alzheimer disease; senile dementia of the Alzheimer type; SDAT; Alzheimer's

Overview

Historical Perspective

Classification

Pathophysiology

Epidemiology and Demographics

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD), also called Alzheimer disease, Senile Dementia of the Alzheimer Type (SDAT) or simply Alzheimer's, is the most common form of dementia.

Although each sufferer experiences Alzheimer's in a unique way, there are many common symptoms.[1] The earliest observable symptoms are often mistakenly thought to be 'age-related' changes, or manifestations of stress.[2] The most commonly recognized symptom of early Alzheimer's disease is memory loss, usually the forgetting of recently learned facts. As the disease advances, symptoms include confusion, irritability and aggression, mood swings, language breakdown, long-term memory loss, and the general withdrawal of the sufferer as their senses decline.[2][3] Gradually, bodily functions are lost, ultimately leading to death.[4] When a doctor or physician has been notified, and AD is suspected, the diagnosis is usually further supported by behavioral assessments and cognitive tests, often followed by a brain scan if available.[5] Individual prognosis is difficult to assess, as the duration of the disease varies. AD develops for an indeterminate period of time before becoming fully apparent, and it can progress undiagnosed for years. The mean life expectancy following diagnosis is approximately seven years.[6] Fewer than three percent of individuals live more than fourteen years after diagnosis.[7]

The cause of Alzheimer's disease is poorly understood. Research indicates that the disease is associated with plaques and tangles in the brain.[8] Currently-used treatments offer a small symptomatic benefit. No treatments to halt the progression of the disease are yet available. As of 2010, more than 700 clinical trials were investigating possible treatments for AD, but it is unknown if any of them will prove successful.[9] Many measures have been suggested for the prevention of Alzheimer's disease, but the value of these measures is unproven in slowing the course and reducing the severity of the disease. Mental stimulation, exercise, and a balanced diet are often recommended as both a possible prevention and a sensible way of managing the disease.[10]

Because AD cannot be cured, management of patients is essential as the disease progresses. The role of the main caregiver is often taken by a spouse or a close relative.[11] Alzheimer's disease is known for placing a great burden on caregivers; the pressures can be wide-ranging, affecting social, psychological, physical, and economic components of the caregiver's life.[12][13][14] In developed countries, AD is one of the most economically costly diseases to society.[15][16]

Diagnosis

Dementia is a clinical condition rather than an exact diagnosis. Alzheimer's disease is usually diagnosed clinically, using the patient history, collateral history from relatives, and clinical observations, based on the presence of characteristic neurological and neuropsychological features and the absence of alternative conditions.[17][18] Advanced medical imaging with CT or MRI, and with SPECT or PET may also be used to help to diagnose the subtype of dementia and exclude other cerebral pathology.[19] Neuropsychological evaluation including memory testing and assessment of intellectual functioning can further characterize the dementia.[2] Medical organizations have created diagnostic criteria to ease and standardize the process for practicing physicians. Sometimes the diagnosis can be confirmed on autopsy when brain material is available and can be examined histologically and histochemically.[20]

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer of the NINCDS-ADRDA (National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association) are among the most commonly used criteria for diagnosing AD.[21] These criteria require that the presence of cognitive impairment and a suspected dementia syndrome be confirmed by neuropsychological testing for a clinical diagnosis of possible or probable AD, while they require histopathologic confirmation (microscopic examination of brain tissue) for the definitive diagnosis. They have shown good reliability and validity.[22] They specify as well eight cognitive domains that may be impaired in AD (i.e., memory, language, perceptual skills, attention, constructive abilities, orientation, problem solving and functional abilities). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) criteria published by the American Psychiatric Association are similar to the NINCDS-ADRDA Alzheimer's Criteria.[23][24]

Diagnostic tools

Neuropsychological screening tests such as the Mini mental state examination (MMSE) are widely used to evaluate the cognitive impairments needed for diagnosis, but more comprehensive batteries are necessary for high reliability by this method, especially in the earliest stages of the disease.[25][26] The neurological examination in early AD is often normal independent of cognitive impairment, but is key for diagnosis of the other dementing disorders. Therefore, neurological examination is crucial in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias.[2] In addition, interviews with family members are also utilised in the assessment of the disease. Caregivers can supply important information on the daily living abilities, as well how the patient's mental function has changed over time. [27] This is especially important since a patient with AD is commonly unaware of his or her own deficits (anosognosia).[28] Many times families also have difficulties in the detection of initial dementia symptoms and in adequately communicating them to a physician.[29] Finally, supplemental testing may provide extra information on features of the disease, or may rule out other diagnoses. Examples are blood tests, which can identify other causes for dementia different than AD,[2] which may even be reversible.[30] psychological tests for depression are also important, as depression can both co-occur with AD or even be at the origin of the patient's cognitive impairment.[31][32]

The functional neuroimaging modalities of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) may also be used in the diagnosis Alzheimer's.[33] In some cases, the ability of SPECT to differentiate Alzheimer's disease from other possible causes in a patient already known to be suffering from dementia may be superior to attempts to differentiate the cause of dementia cause by mental testing and history.[34] A new technique known as "PiB PET" has been developed for directly and clearly imaging beta-amyloid deposits in vivo using a contrasting tracer that binds selectively to the Abeta deposits.[35][36][37] Another recent objective marker of the disease is the analysis of cerebrospinal fluid for amyloid beta or tau proteins.[38] Both advances (neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid analysis) have led to the proposal of new diagnostic criteria.[21][2]

Prevention

Specific measures to delay or prevent the onset of AD are lacking. This is due to contradictory results in global studies, as well as a paucity of proven causal relationships between risk factors and the disease.[39] Modifiable factors such as diet, cardiovascular risks, pharmaceutical products, or intellectual activities have all been evaluated with epidemiological studies to see if they increase a population's risk of developing AD.[40]

The components of a Mediterranean diet, which include fruit and vegetables, bread, wheat and other cereals, olive oil, fish, and red wine, may reduce the risk and course of Alzheimer's disease. There is evidence that frequent and moderate consumption of alcohol (beer, wine or distilled spirits) reduces the risk of the disease,[41] [42] but it is still considered premature to make dietary recommendations on this basis.[43][44] Vitamins E, B, and C, or folic acid have appeared to be related to a reduced risk of AD,[45] but other studies indicate that they do not have any significant effect on the onset or course of the disease, but may have important secondary effects in conjunction with other therapies.[46] Curcumin in curry has shown some effectiveness in preventing brain damage in mouse models.[47]

Although cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking, are associated with a higher risk of onset and course of AD,[48][49] statins, which are cholesterol lowering drugs, have not been effective in preventing or improving the course of the disease.[50][51] However long-term usage of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs), is associated with a reduced likelihood of developing AD in some individuals.[52][53][54]

Other pharmaceutical therapies such as female hormone replacement therapy are no longer thought to prevent dementia,[55][56] and a 2007 systematic review concluded that there was inconsistent and unconvincing evidence that ginkgo has any positive effect on dementia or cognitive impairment.[57]

Intellectual activities such as playing chess, completing crossword puzzles or regular social interaction may also delay the onset or reduce the severity of Alzheimer's disease.[58][59] Bilingualism is also related to a later onset of Alzheimer's disease.[60]

Management

There is no known cure for Alzheimer's disease. Available treatments offer relatively small symptomatic benefit but remain palliative in nature. Current treatments can be divided into pharmaceutical, psychosocial and caregiving.

Pharmaceutical

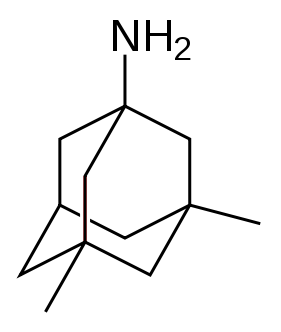

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMEA)currently approve four medications to treat the cognitive manifestations of AD. Three are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and the other is memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist. No drug is currently able to delay or halt the progression of the disease.

Because reduction in cholinergic neuronal activity is well known in Alzheimer's disease,[61] acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are employed to reduce the rate at which acetylcholine (ACh) is broken down. This increases the concentration of ACh in the brain, thereby combatting the loss of ACh caused by the death of the cholinergic neurons.[62] Cholinesterase inhibitors currently approved include donepezil (brand name Aricept),[63] galantamine (Razadyne),[64] and rivastigmine (branded as Exelon,[65] and Exelon Patch[66]). There is also evidence for the efficacy of these medications in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease,[67] and some evidence for their use in the advanced stage. Only donepezil is approved for treatment of advanced AD dementia.[68] The use of these drugs in mild cognitive impairment has not shown any effect in delaying the onset of AD.[69] The most common side effects include nausea and vomiting, both of which are linked to cholinergic excess. These side effects arise in approximately ten to twenty percent of users and are mild to moderate in severity. Less common secondary effects include muscle cramps; decreased heart rate (bradycardia), decreased appetite and weight, and increased gastric acid.[70][71][72][73]

Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter of the nervous system. Excessive amounts of glutamate in the brain can lead to cell death through a process called excitotoxicity which consists of the overstimulation of glutamate receptors. Excitotoxicity occurs not only in Alzheimer's disease, but also in other neurological diseases such as Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis.[74] Memantine (brand names Akatinol, Axura, Ebixa/Abixa, Memox and Namenda),[75] is a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist first used as an anti-influenza agent. It acts on the glutamatergic system by blocking NMDA glutamate receptors and inhibits their overstimulation by glutamate.[74] Memantine has been shown to be moderately efficacious in the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Its effects in the initial stages of AD are unknown.[76] Reported adverse events with memantine are infrequent and mild, including hallucinations, confusion, dizziness, headache and fatigue.[77] Memantine used in combination with donepezil has been shown to be "of statistically significant but clinically marginal effectiveness".[78]

Neuroleptic anti-psychotic drugs commonly given to Alzheimer's patients with behavioural problems are modestly useful in reducing aggression and psychosis, but are associated with serious adverse effects, such as cerebrovascular events, movement difficulties or cognitive decline. These side effects do not permit the routine use of these medications.[79][80][81]

Psychosocial intervention

Psychosocial interventions are used as an adjunct to pharmaceutical treatment and can be classified within behavior, emotion, cognition or stimulation oriented approaches. Research on efficacy is unavailable and rarely specific to Alzheimer's disease, focusing instead on dementia as a whole.[82]

Behavioral interventions attempt to identify and reduce the antecedents and consequences of problem behaviors. This approach has not shown success in the overall functioning of patients,[83] but can help to reduce some specific problem behaviors, such as incontinence.[84] There is still a lack of high quality data on the effectiveness of these techniques in other behavior problems such as wandering.[85][86]

Emotion-oriented interventions include reminiscence therapy, validation therapy, supportive psychotherapy, sensory integration or snoezelen, and simulated presence therapy. Supportive psychotherapy has received little or no formal scientific study, but some clinicians find it useful in helping mildly impaired patients adjust to their illness.[82] Reminiscence therapy (RT) involves the discussion of past experiences individually or in group, often with the aid of photographs, household items, music and sound recordings, or other familiar items from the past. Although there are few quality studies on the effectiveness of RT it may be beneficial for cognition and mood.[87] Simulated presence therapy (SPT) is based on attachment theories and is normally carried out playing a recording with voices of the closest relatives of the patient. There is preliminary evidence indicating that SPT may reduce anxiety and challenging behaviors.[88][89] Finally, validation therapy is based on acceptance of the reality and personal truth of another's experience, while sensory integration is based on exercises aimed to stimulate senses. There is little evidence to support the usefulness of these therapies.[90][91]

The aim of cognition-oriented treatments, which include reality orientation and cognitive retraining is the restoration of cognitive deficits. Reality orientation consists of the presentation of information about time, place or person in order to ease the the patient's understanding of their surroundings. On the other hand, cognitive retraining tries to improve impaired capacities by exercising mental abilities. Both have shown some efficacy improving cognitive capacities,[92][93] although in some works these effects were transient. Negative effects, such as frustration, have also been reported.[82]

Stimulation-oriented treatments include art, music and pet therapies, exercise, and any other kind of recreational activities for patients. Stimulation has modest support for improving behavior, mood, and, to a lesser extent, function. Nevertheless, as important as these effects are, the main support for the use of stimulation therapies is the improvement in the patient's daily life, as opposed to improving the underlying disease course.[82]

Caregiving

Since there is no cure for Alzheimer's, caregiving is an essential part of the treatment. Due to the eventual inability for the sufferer to self-care, Alzheimer's has to be carefully care-managed. Home care in the familiar surroundings of home may delay onset of some symptoms and delay or eliminate the need for more professional and costly levels of care.[94] Many family members choose to look after their relative,[95] but two-thirds of nursing home residents have dementias.[96]

Modifications to the living environment and lifestyle of the Alzheimer's patient can improve functional performance and ease caretaker burden. Assessment by an occupational therapist is often indicated. Adherence to simplified routines and labeling of household items to cue the patient can aid with activities of daily living, while placing safety locks on cabinets, doors, and gates and securing hazardous chemicals can prevent accidents and wandering. Changes in routine or environment can trigger or exacerbate agitation, whereas well-lit rooms, adequate rest, and avoidance of excess stimulation all help prevent such episodes.[97][98] Appropriate social and visual stimulation can improve function by increasing awareness and orientation. For instance, boldly colored tableware aids those with severe AD, helping people overcome a diminished sensitivity to visual contrast to increase food and beverage intake.[99]

Clinical research

As of 2008, the safety and efficacy of more than 400 pharmaceutical treatments are being investigated in clinical trials worldwide, and approximately one-fourth of these compounds are in Phase III trials, which is the last step prior to review by regulatory agencies.[100] It is unknown as to whether any of these trials will ultimately prove successful in treating the disease.

A critical area of clinical research is focused on treating the underlying disease pathology. Reduction of amyloid beta levels is a common target of compounds under investigation. Immunotherapy or vaccination for the amyloid protein is one treatment modality under study. Unlike vaccines which seek to prevent disease, this therapy would be used to treat diagnosed patients, and is based upon the concept of training the immune system to recognize, attack, and reverse deposition of amyloid, thereby altering the course of the disease.[101] An example of such a vaccine under investigation is ACC-001.[102][103] Similar agents are bapineuzumab, an antibody designed as identical to the naturally-induced anti-amyloid antibody,[104] and MPC-7869, a selective amyloid beta-42 lowering agent.[105] Other approaches are neuroprotective agents, such as AL-108,[106] metal-protein interaction attenuation agents, such as PBT2,[107] or tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor fusion proteins, such as etanercept.[108][109][110] There are also many basic investigations attempting to increase the knowledge on the origin and mechanisms of the disease that may lead to new treatments.

Society and culture

Social costs

Because the median age of the industrialised world's population is gradually increasing, Alzheimer's is a major public health challenge. Much of the concern about the solvency of governmental social safety nets is founded on estimates of the costs of caring for baby boomers, assuming that they develop Alzheimer's in the same proportions as earlier generations. For this reason, money spent informing the public of available effective prevention methods may yield disproportionate benefits.[111]

Caregiving burden

The role of family caregivers has become more prominent in both reducing the social cost of care and improving the quality of life of the patient. Home-based care also can have economic, emotional, and psychological costs to the patient's family. Although family members in particular often express the desire to care for the sufferer to the end,[112] Alzheimer's disease is known for effecting a high burden on caregivers.[95]

Alzheimer's disease can incur a variety of stresses on the caregivers: typical complaints are stress, depression, and an inability to cope. Reasons for these complaints can include: high-demands on the caregiver's concentration, as Alzheimer's sufferers have a decreasing regard for their own safety (and can wander when unattended, for example); the lack of gratitude received when the sufferer is unaware of the help being given; and the lack of satisfaction when the sufferer's condition does not abate. Alzheimer's sufferers can be verbally and physically aggressive, and can stubbornly refuse to be helped. Aggression in particular can lead to a temptation to retaliate, which can put both the sufferer and carer at risk. It is additionally stressful for caregivers who are friends and family to witness a sufferer lose his or her identity, and eventually be unable to recognise them.[95]

Family caregivers often give up time from work and forego pay to spend 47 hours per week on average with the person with AD. From a 2006 survey of US patients with long term care insurance, direct and indirect costs of caring for an Alzheimer's patient average $77,500 per year.[113]

References

- ↑

"What is Alzheimer's disease?". Alzheimers.org.uk. 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-21. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M; et al. (2007). "Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer's disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline". Eur. J. Neurol. 14 (1): e1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01605.x. PMID 17222085. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Tabert MH, Liu X, Doty RL, Serby M, Zamora D, Pelton GH, Marder K, Albers MW, Stern Y, Devanand DP (2005). "A 10-item smell identification scale related to risk for Alzheimer's disease". Ann. Neurol. 58 (1): 155–160. doi:10.1002/ana.20533. PMID 15984022.

- ↑ "Understanding stages and symptoms of Alzheimer's disease". National Institute on Aging. 2007-10-26. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "Alzheimer's diagnosis of AD". Alzheimer's Research Trust. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ↑ Mölsä PK, Marttila RJ, Rinne UK (1986). "Survival and cause of death in Alzheimer's disease and multi-infarct dementia". Acta Neurol. Scand. 74 (2): 103–7. PMID 3776457. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Mölsä PK, Marttila RJ, Rinne UK (1995). "Long-term survival and predictors of mortality in Alzheimer's disease and multi-infarct dementia". Acta Neurol. Scand. 91 (3): 159–64. PMID 7793228. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑

- ↑ "Alzheimer's Disease Clinical Trials". US National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- ↑ "Can Alzheimer's disease be prevented" (pdf). National Institute on Aging. 2006-08-29. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ↑ "The MetLife study of Alzheimer's disease: The caregiving experience" (PDF). MetLife Mature Market Institute. 2006. Retrieved 2008-02-12. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Thompson CA, Spilsbury K, Hall J, Birks Y, Barnes C, Adamson J (2007). "Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia". BMC Geriatr. 7: 18. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-7-18. PMC 1951962. PMID 17662119.

- ↑ Schneider J, Murray J, Banerjee S, Mann A (1999). "EUROCARE: a cross-national study of co-resident spouse carers for people with Alzheimer's disease: I—Factors associated with carer burden". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 14 (8): 651–661. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199908)14:8<651::AID-GPS992>3.0.CO;2-B. PMID 10489656. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Murray J, Schneider J, Banerjee S, Mann A (1999). "EUROCARE: a cross-national study of co-resident spouse carers for people with Alzheimer's disease: II--A qualitative analysis of the experience of caregiving". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 14 (8): 662–667. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199908)14:8<662::AID-GPS993>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 10489657. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Bonin-Guillaume S, Zekry D, Giacobini E, Gold G, Michel JP (2005). "Impact économique de la démence (English: The economical impact of dementia)". Presse Med (in French). 34 (1): 35–41. ISSN 0755-4982. PMID 15685097. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Meek PD, McKeithan K, Schumock GT (1998). "Economic considerations in Alzheimer's disease". Pharmacotherapy. 18 (2 Pt 2): 68–73, discussion 79–82. PMID 9543467.

- ↑ Mendez MF (2006). "The accurate diagnosis of early-onset dementia". International Journal of Psychiatry Medicine. 36 (4): 401–412. PMID 17407994.

- ↑ Klafki HW, Staufenbiel M, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J (2006). "Therapeutic approaches to Alzheimer's disease". Brain. 129 (Pt 11): 2840–2855. doi:10.1093/brain/awl280. PMID 17018549.

- ↑

"Dementia: Quick reference guide" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2006. ISBN 1-84629-312-X. Retrieved 2008-02-22. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM (1984). "Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease". Neurology. 34 (7): 939–44. PMID 6610841.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O'brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P (2007). "Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria". Lancet Neurology. 6 (8): 734–746. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. PMID 17616482.

- ↑ Blacker D, Albert MS, Bassett SS, Go RC, Harrell LE, Folstein MF (1994). "Reliability and validity of NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for Alzheimer's disease. The National Institute of Mental Health Genetics Initiative". Archives of Neurology. 51 (12): 1198–1204. PMID 7986174.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders, 4th Edition Text Revision. Washington DC.

- ↑ Ito N (1996). "Clinical aspects of dementia". Hokkaido Igaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 71 (3): 315–320. PMID 8752526.

- ↑ Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ (1992). "The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review". J Am Geriatr Soc. 40 (9): 922–935. PMID 1512391.

- ↑ Pasquier F (1999). "Early diagnosis of dementia: neuropsychology". J. Neurol. 246 (1): 6–15. PMID 9987708.

- ↑ Harvey PD, Moriarty PJ, Kleinman L, Coyne K, Sadowsky CH, Chen M, Mirski DF (2005). "The validation of a caregiver assessment of dementia: the Dementia Severity Scale". Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 19 (4): 186–194. PMID 16327345.

- ↑ Antoine C, Antoine P, Guermonprez P, Frigard B (2004). "Awareness of deficits and anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease". Encephale (in French). 30 (6): 570–577. PMID 15738860.

- ↑ Cruz VT, Pais J, Teixeira A, Nunes B (2004). "The initial symptoms of Alzheimer disease: caregiver perception". Acta Med Port (in Portuguese). 17 (6): 435–444. PMID 16197855.

- ↑ Clarfield AM (2003). "The decreasing prevalence of reversible dementias: an updated meta-analysis". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (18): 2219–29. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.18.2219. PMID 14557220.

- ↑ Geldmacher DS, Whitehouse PJ (1997). "Differential diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease". Neurology. 48 (5 Suppl 6): S2–9. PMID 9153154.

- ↑ Potter GG, Steffens DC (2007). "Contribution of depression to cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults". Neurologist. 13 (3): 105–117. doi:10.1097/01.nrl.0000252947.15389.a9. PMID 17495754.

- ↑ Bonte FJ, Harris TS, Hynan LS, Bigio EH, White CL (2006). "Tc-99m HMPAO SPECT in the differential diagnosis of the dementias with histopathologic confirmation". Clinical nuclear medicine. 31 (7): 376–378. doi:10.1097/01.rlu.0000222736.81365.63. PMID 16785801.

- ↑ Dougall NJ, Bruggink S, Ebmeier KP (2004). "Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of 99mTc-HMPAO-SPECT in dementia". American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 12 (6): 554–570. doi:10.1176/appi.ajgp.12.6.554. PMID 15545324.

- ↑ Kemppainen NM, Aalto S, Karrasch M, Någren K, Savisto N, Oikonen V, Viitanen M, Parkkola R, Rinne JO (2008). "Cognitive reserve hypothesis: Pittsburgh Compound B and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in relation to education in mild Alzheimer's disease". Ann. Neurol. 63 (1): 112–8. doi:10.1002/ana.21212. PMID 18023012.

- ↑

Ikonomovic MD, Klunk WE, Abrahamson EE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Tsopelas ND, Lopresti BJ, Ziolko S, Bi W, Paljug WR, Debnath ML, Hope CE, Isanski BA, Hamilton RL, Dekosky ST (March 2008). "Post-mortem correlates of in vivo PiB-PET amyloid imaging in a typical case of Alzheimer's disease". Brain. doi:doi:10.1093/brain/awn016 Check

|doi=value (help). PMID 18339640. - ↑ Jack CR, Lowe VJ, Senjem ML; et al. (2008). "11C PiB and structural MRI provide complementary information in imaging of Alzheimer's disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment". Brain. 131 (Pt 3): 665–80. doi:10.1093/brain/awm336. PMID 18263627.

- ↑ Marksteiner J, Hinterhuber H, Humpel C (2007). "Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: beta-amyloid(1-42), tau, phospho-tau-181 and total protein". Drugs Today. 43 (6): 423–431. doi:10.1358/dot.2007.43.6.1067341. PMID 17612711.

- ↑ Prevention recommendations not supported:

- Kawas CH (2006). "Medications and diet: protective factors for AD?". Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 20 (3 Suppl 2): S89–96. PMID 16917203.

- Luchsinger JA, Mayeux R (2004). "Dietary factors and Alzheimer's disease". Lancet Neurol. 3 (10): 579–87. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00878-6. PMID 15380154.

- Luchsinger JA, Noble JM, Scarmeas N (2007). "Diet and Alzheimer's disease". Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 7 (5): 366–72. doi:10.1007/s11910-007-0057-8. PMID 17764625.

- ↑ Szekely CA, Breitner JC, Zandi PP (2007). "Prevention of Alzheimer's disease". Int Rev Psychiatry. 19 (6): 693–706. doi:10.1080/09540260701797944. PMID 18092245.

- ↑ Alcohol:

- Mulkamal KJ; et al. (2003-03-19). "Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of dementia in older adults". Journal of the American Medical Association. 289: 1405–1413.

- Ganguli M; et al. (2005). "Alcohol consumption and cognitive function in late life: A longitudinal community study". Neurology. 65: 1210–1217.

- Huang W; et al. (2002). "Alcohol consumption and incidence of dementia in a community sample aged 75 years and older". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 55 (10): 959–964.

- Rodgers B; et al. (2005). "Non-linear relationships between cognitive function and alcohol consumption in young, middle-aged and older adults: The PATH Through Life Project". Addiction. 100 (9): 1280–1290.

- Anstey KJ; et al. (2005). "Lower cognitive test scores observed in alcohol are associated with demographic, personality, and biological factors: The PATH Through Life Project". Addiction. 100 (9): 1291–1301, .Espeland, M.; et al. (2006). "Association between alcohol intake and domain-specific cognitive function in older women". Neuroepidemiology. 1 (27): 1–12.

- Stampfer MJ; et al. (2005). "Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cognitive function in women". New England Journal of Medicine. 352: 245–253.

- Ruitenberg A; et al. (2002). "Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: the Rotterdam Study". Lancet. 359 (9303): 281–286.

- Scarmeas N; et al. (2006-04-18). "Mediterranean diet and risk for Alzheimer's disease". Annals of Neurology.

- ↑ Mediterranean diet:

- Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA (2006). "Mediterranean diet, Alzheimer disease, and vascular mediation". Arch. Neurol. 63 (12): 1709–1717. doi:10.1001/archneur.63.12.noc60109. PMID 17030648.

- Scarmeas N, Luchsinger JA, Mayeux R, Stern Y (2007). "Mediterranean diet and Alzheimer disease mortality". Neurology. 69 (11): 1084–93. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000277320.50685.7c. PMID 17846408.

- Barberger-Gateau P, Raffaitin C, Letenneur L, Berr C, Tzourio C, Dartigues JF, Alpérovitch A (2007). "Dietary patterns and risk of dementia: the Three-City cohort study". Neurology. 69 (20): 1921–1930. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000278116.37320.52. PMID 17998483.

- Dai Q, Borenstein AR, Wu Y, Jackson JC, Larson EB (2006). "Fruit and vegetable juices and Alzheimer's disease: the Kame Project". American Journal of Medicine. 119 (9): 751–759. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.045. PMID 16945610.

- Savaskan E, Olivieri G, Meier F, Seifritz E, Wirz-Justice A, Müller-Spahn F (2003). "Red wine ingredient resveratrol protects from beta-amyloid neurotoxicity". Gerontology. 49 (6): 380–383. doi:10.1159/000073766. PMID 14624067.

- ↑

Luchsinger JA, Mayeux R (2004 Oct). "Dietary factors and Alzheimer's disease". Lancet Neurology. 3 (10): 579–587. PMID 15380154.

Available data do not permit definitive conclusions regarding diet and AD or specific recommendations on diet modification for the prevention of AD.

Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑

Kawas CH (2006 Jul-Sep). "Medications and diet: protective factors for AD?". Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 20 (3 Suppl 2): S89–96. PMID 16917203.

Evidence regarding dietary and supplemental intake of vitamins E, C, and folate, and studies of alcohol and wine intake are also reviewed. At present, there is insufficient evidence to make public health recommendations, but these studies can provide potentially important clues and new avenues for clinical and laboratory research.

Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ Vitamins:

- Morris MC, Schneider JA, Tangney CC (2006). "Thoughts on B-vitamins and dementia". J. Alzheimers Dis. 9 (4): 429–33. PMID 16917152.

- Alzheimer's Association. "Vitamin E".

- Landmark K (2006). "[Could intake of vitamins C and E inhibit development of Alzheimer dementia?]". Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. (in Norwegian). 126 (2): 159–61. PMID 16415937.

- Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Miller J, Green R, Mayeux R (2007). "Relation of higher folate intake to lower risk of Alzheimer disease in the elderly". Arch. Neurol. 64 (1): 86–92. doi:10.1001/archneur.64.1.86. PMID 17210813.

- ↑ Vitamins only of secondary benefit:

- Morris MC, Evans DA, Schneider JA, Tangney CC, Bienias JL, Aggarwal NT (2006). "Dietary folate and vitamins B-12 and B-6 not associated with incident Alzheimer's disease". J. Alzheimers Dis. 9 (4): 435–43. PMID 16917153.

- Malouf M, Grimley EJ, Areosa SA (2003). "Folic acid with or without vitamin B12 for cognition and dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD004514. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004514. PMID 14584018.

- Sun Y, Lu CJ, Chien KL, Chen ST, Chen RC (2007). "Efficacy of multivitamin supplementation containing vitamins B6 and B12 and folic acid as adjunctive treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor in Alzheimer's disease: a 26-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in Taiwanese patients". Clin Ther. 29 (10): 2204–14. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.10.012. PMID 18042476.

- Boothby LA, Doering PL (2005). "Vitamin C and vitamin E for Alzheimer's disease". Ann Pharmacother. 39 (12): 2073–80. doi:10.1345/aph.1E495. PMID 16227450.

- Gray SL, Anderson ML, Crane PK, Breitner JC, McCormick W, Bowen JD, Teri L, Larson E (2008). "Antioxidant vitamin supplement use and risk of dementia or Alzheimer's disease in older adults". J Am Geriatr Soc. 56 (2): 291–295. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01531.x. PMID 18047492.

- ↑ Curcumin in diet:

- Garcia-Alloza M, Borrelli LA, Rozkalne A, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ (2007). "Curcumin labels amyloid pathology in vivo, disrupts existing plaques, and partially restores distorted neurites in an Alzheimer mouse model". Journal of Neurochemistry. 102 (4): 1095–1104. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04613.x. PMID 17472706.

- Lim GP, Chu T, Yang F, Beech W, Frautschy SA, Cole GM (2001). "The curry spice curcumin reduces oxidative damage and amyloid pathology in an Alzheimer transgenic mouse". Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (21): 8370–8377. PMID 11606625.

- ↑ Rosendorff C, Beeri MS, Silverman JM (2007). "Cardiovascular risk factors for Alzheimer's disease". Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 16 (3): 143–9. doi:10.1111/j.1076-7460.2007.06696.x. PMID 17483665.

- ↑ Gustafson D, Rothenberg E, Blennow K, Steen B, Skoog I (2003). "An 18-year follow-up of overweight and risk of Alzheimer disease". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (13): 1524–1528. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.13.1524. PMID 12860573.

- ↑ Reiss AB, Wirkowski E (2007). "Role of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in neurological disorders : progress to date". Drugs. 67 (15): 2111–2120. PMID 17927279.

- ↑ Kuller LH (2007). "Statins and dementia". Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 9 (2): 154–161. doi:10.1007/s11883-007-0012-9. PMID 17877925.

- ↑ Szekely CA, Breitner JC, Fitzpatrick AL, Rea TD, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Zandi PP (2008). "NSAID use and dementia risk in the Cardiovascular Health Study: role of APOE and NSAID type". Neurology. 70 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000284596.95156.48. PMID 18003940.

- ↑ "Long-term use of ibuprofen may reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, a large US study reports". BBC. 2008-05-05.

- ↑ "Ibuprofen Linked to Reduced Alzheimer's Risk". Washington Post. 2008-05-05.

- ↑ Craig MC, Murphy DG (2007). "Estrogen: effects on normal brain function and neuropsychiatric disorders". Climacteric. 10 Suppl 2: 97–104. doi:10.1080/13697130701598746. PMID 17882683.

- ↑ Mori K, Takeda M (2007). "Hormone replacement Up-to-date. Hormone replacement therapy and brain function". Clin Calcium (in Japanese). 17 (9): 1349–1354. doi:CliCa070913491354 Check

|doi=value (help). PMID 17767023. - ↑ Birks J, Grimley Evans J (2007). "Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD003120. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003120.pub2. PMID 17443523. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ↑ Verghese J, Lipton R, Katz M, Hall C, Derby C, Kuslansky G, Ambrose A, Sliwinski M, Buschke H (2003). "Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly". N Engl J Med. 348 (25): 2508–2516. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022252. PMID 12815136.

- ↑ Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Arnold SE, Wilson RS (2006). "The effect of social networks on the relation between Alzheimer's disease pathology and level of cognitive function in old people: a longitudinal cohort study". Lancet Neurol. 5 (5): 406–412. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70417-3. PMID 16632311.

- ↑ Bialystok E, Craik FIM, Freedman M (2007). "Bilingualism as a protection against the onset of symptoms of dementia". Neuropsychologia. 42 (2): 459–464. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.009.

- ↑ Geula C, Mesulam MM (1995). "Cholinesterases and the pathology of Alzheimer disease". Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 9 Suppl 2: 23–8. PMID 8534419.

- ↑ Stahl SM (2000). "The new cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease, Part 2: illustrating their mechanisms of action". J Clin Psychiatry. 61 (11): 813–814. PMID 11105732.

- ↑ "Donepezil". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ "Galantamine". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ "Rivastigmine". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ "Rivastigmine Transdermal". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ↑ Birks J (2006). "Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD005593. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005593. PMID 16437532.

- ↑ Birks J, Harvey RJ (2006). "Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer's disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD001190. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001190.pub2. PMID 16437430.

- ↑ Raschetti R, Albanese E, Vanacore N, Maggini M (2007). "Cholinesterase inhibitors in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of randomised trials". PLoS Med. 4 (11): e338. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040338. PMID 18044984.

- ↑ "Aricept and Aricept ODT Product Insert" (PDF). Eisai and Pfizer. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ↑ "Razadyne ER U.S. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Ortho-McNeil Neurologics. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ "Exelon ER U.S. Prescribing Information" (PDF). Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ "Exelon U.S. Prescribing Information" (PDF). Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Lipton SA (2006). "Paradigm shift in neuroprotection by NMDA receptor blockade: memantine and beyond". Nat Rev Drug Discov. 5 (2): 160–170. doi:10.1038/nrd1958. PMID 16424917.

- ↑ "Memantine". US National Library of Medicine (Medline). 2004-01-04. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ↑ Areosa Sastre A, McShane R, Sherriff F (2004). "Memantine for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003154. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003154.pub2. PMID 15495043.

- ↑ "Namenda Prescribing Information" (PDF). Forest Pharmaceuticals. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A; et al. (2008). "Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline". Annals of Internal Medicine. 148 (5): 379–397. PMID 18316756.

- ↑ Ballard C, Waite J (2006). "The effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of aggression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD003476. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003476.pub2. PMID 16437455.

- ↑ Ballard C, Lana MM, Theodoulou M; et al. (2008). "A Randomised, Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial in Dementia Patients Continuing or Stopping Neuroleptics (The DART-AD Trial)". PLoS Med. 5 (4): e76. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050076. PMID 18384230.

- ↑ Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K (2005). "Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence". JAMA. 293 (5): 596–608. doi:10.1001/jama.293.5.596. PMID 15687315.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Alzheimer's disease and Other Dementias" (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. October 2007. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423967.152139. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ Bottino CM, Carvalho IA, Alvarez AM; et al. (2005). "Cognitive rehabilitation combined with drug treatment in Alzheimer's disease patients: a pilot study". Clin Rehabil. 19 (8): 861–869. doi:10.1191/0269215505cr911oa. PMID 16323385.

- ↑ Doody RS, Stevens JC, Beck C; et al. (2001). "Practice parameter: management of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 56 (9): 1154–1166. PMID 11342679.

- ↑ Hermans DG, Htay UH, McShane R (2007). "Non-pharmacological interventions for wandering of people with dementia in the domestic setting". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD005994. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005994.pub2. PMID 17253573.

- ↑ Robinson L, Hutchings D, Dickinson HO; et al. (2007). "Effectiveness and acceptability of non-pharmacological interventions to reduce wandering in dementia: a systematic review". Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 22 (1): 9–22. doi:10.1002/gps.1643. PMID 17096455.

- ↑ Woods B, Spector A, Jones C, Orrell M, Davies S (2005). "Reminiscence therapy for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD001120. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001120.pub2. PMID 15846613.

- ↑ Peak JS, Cheston RI (2002). "Using simulated presence therapy with people with dementia". Aging Ment Health. 6 (1): 77–81. doi:10.1080/13607860120101095. PMID 11827626.

- ↑ Camberg L, Woods P, Ooi WL; et al. (1999). "Evaluation of Simulated Presence: a personalised approach to enhance well-being in persons with Alzheimer's disease". J Am Geriatr Soc. 47 (4): 446–452. PMID 10203120.

- ↑ Neal M, Briggs M (2003). "Validation therapy for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001394. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001394. PMID 12917907.

- ↑ Chung JC, Lai CK, Chung PM, French HP (2002). "Snoezelen for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003152. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003152. PMID 12519587.

- ↑ Spector A, Orrell M, Davies S, Woods B (2000). "WITHDRAWN: Reality orientation for dementia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD001119. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001119.pub2. PMID 17636652.

- ↑ Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B; et al. (2003). "Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial". Br J Psychiatry. 183: 248–254. doi:10.1192/bjp.183.3.248. PMID 12948999.

- ↑ Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, Newcomer R (2005). "Early community-based service utilization and its effects on institutionalization in dementia caregiving". Gerontologist. 45 (2): 177–85. PMID 15799982. Retrieved 2008-05-30. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 Selwood A, Johnston K, Katona C, Lyketsos C, Livingston G (2007). "Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia". Journal of Affective Disorders. 101 (1–3): 75–89. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.025. PMID 17173977.

- ↑ "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Alzheimer's disease and Other Dementias" (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. October 2007. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423967.152139. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

- ↑ "Treating behavioral and psychiatric symptoms". Alzheimer's Association. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- ↑ Wenger GC, Burholt V, Scott A (1998). "Dementia and help with household tasks: a comparison of cases and non-cases". Health Place. 4 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1016/S1353-8292(97)00024-5. PMID 10671009.

- ↑ Dunne TE, Neargarder SA, Cipolloni PB, Cronin-Golomb A (2004). "Visual contrast enhances food and liquid intake in advanced Alzheimer's disease". Clinical Nutrition. 23 (4): 533–538. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2003.09.015. PMID 15297089.

- ↑ "Clinical Trials. Found 459 studies with search of: alzheimer". US National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ↑ Vaccination:

- Hawkes CA, McLaurin J (2007). "Immunotherapy as treatment for Alzheimer's disease". Expert Reviews of Neurotherapy. 7 (11): 1535–1548. doi:10.1586/14737175.7.11.1535. PMID 17997702.

- Solomon B (2007). "Clinical immunologic approaches for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease". Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 16 (6): 819–828. doi:10.1517/13543784.16.6.819. PMID 17501694.

- Woodhouse A, Dickson TC, Vickers JC (2007). "Vaccination strategies for Alzheimer's disease: A new hope?". Drugs Aging. 24 (2): 107–119. doi:10.2165/00002512-200724020-00003. PMID 17313199.

- ↑ "Study Evaluating ACC-001 in Mild to Moderate Alzheimers Disease Subjects". Clinical Trial. [FDA clinicaltrials.gov]. 2008-03-11.

- ↑ "Study Evaluating Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of ACC-001 in Subjects With Alzheimer's Disease".

- ↑ "Bapineuzumab in Patients With Mild to Moderate Alzheimer's Disease/ Apo_e4 non-carriers". Clinical Trial. US National Institutes of Health. 2008-02-29. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ↑ "Efficacy Study of MPC-7869 to Treat Patients With Alzheimer's". Clinical Trial. US National Institutes of Health. 2007-12-11. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ↑ "Safety, Tolerability and Efficacy Study to Evaluate Subjects With Mild Cognitive Impairment". Clinical Trial. US National Institutes of Health. 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ↑ "Study Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability and Efficacy of PBT2 in Patients With Early Alzheimer's Disease". Clinical Trial. US National Institutes of Health. 2008-01-13. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ↑ Tobinick E, Gross H, Weinberger A, Cohen H (2006). "TNF-alpha modulation for treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a 6-month pilot study". MedGenMed. 8 (2): 25. PMID 16926764.

- ↑ Griffin WS (2008). "Perispinal etanercept: potential as an Alzheimer therapeutic". J Neuroinflammation. 5: 3. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-5-3. PMID 18186919.

- ↑ Tobinick E (2007). "Perispinal etanercept for treatment of Alzheimer's disease". Curr Alzheimer Res. 4 (5): 550–552. doi:10.2174/156720507783018217. PMID 18220520.

- ↑ Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Suchindran C, Reed P, Wang L, Boustani M, Sudha S (2002). "The public health impact of Alzheimer's disease, 2000–2050: potential implication of treatment advances". Annual Review of Public Health. 23: 213–231. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140525. PMID 11910061.

- ↑ O’Donovan ST. "Dementia caregiving burden and breakdown" (PDF). Forum of Consultant Nurses, Midwives and Allied Health Professionals. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ↑ "The MetLife Study of Alzheimer's Disease: The Caregiving Experience" (PDF). MetLife Mature Market Institute. August 2006. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- Pages with reference errors

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- Pages using citations with accessdate and no URL

- CS1 maint: Unrecognized language

- CS1 errors: DOI

- CS1 maint: Date and year

- CS1 errors: dates

- Disease

- Neurology

- Psychiatry

- Overview complete

- Gerontology