Congestive heart failure chronic pharmacotherapy: Difference between revisions

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

:* Increased risk of recurrent [[genital]] [[fungal]] infections | :* Increased risk of recurrent [[genital]] [[fungal]] infections | ||

* A small reversible reduction in [[eGFR]] following initiation | * A small reversible reduction in [[eGFR]] following initiation | ||

==Beta blockers: Third Step in the Management of Heart Failure== | ==Beta blockers: Third Step in the Management of Heart Failure== | ||

Revision as of 08:23, 18 February 2022

| Resident Survival Guide |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Rim Halaby, M.D. [2]

Overview

There are several goals in the chronic management of systolic heart failure. The management of diastolic heart failure is discussed elsewhere. One goal of therapy is to improve the patient's symptoms, exercise tolerance and quality of life. Diuretics, along with regular assessment of the patient's weight, minimizes fluid accumulation and the accompanying symptoms of dyspnea and orthopnea. Another goal is to reduce hospitalization and mortality. To achieve the second goal, patients with chronic heart failure should be administered an ACE inhibitor (or ARB if they are ACE intolerant) and a beta blocker. If the patient remains symptomatic, additional therapy may include an aldosterone antagonist.

Drugs recommended in all patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

Medications indicated in patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA class II–IV) heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (LVEF <_40%)

| Recommendations for screening sleep apnea in patients with bradycardia or conduction disorder |

| (Class I, Level of Evidence A): |

|

❑ ACE-I is recommended for patients with HFrEF to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization and death |

| (Class I, Level of Evidence B): |

|

❑ Sacubitril/valsartan is recommended as a replacement for an ACE-I in patients with HFrEF to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization and death |

| The above table adopted from 2021 ESC Guideline |

|---|

Other medications in HFrEF in patients with NYHA 2-4

| Recommendations for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and NYHA 2-4 |

| Loop diuretics (Class I, Level of Evidence C): |

|

❑ Loop diuretics are recommended in patients with HFrEF with signs and/or symptoms of congestion to improve HF symptoms, exercise

capacity, and reduce HF hospitalizations |

| ARB (Class I, Level of Evidence B): |

|

❑ ARB is recommended in symptomatic patients to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization and cardiovascular death for whom unable to tolerate an ACE-I or ARNI (patients should also receive a beta-blocker and MRA) |

| If-channel inhibitor :(Class IIa, Level of Evidence B) : |

|

❑Ivabradine should be considered in symptomatic patients with LVEF <_35%, sinus rhythm on ECG and a resting heart rate >_70 b.p.m despite treatment with maximum tolerated beta-blocker, ACE-I/(or ARNI), and an MRA, to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization and cardiovascular death |

| If-channel inhibitor : (Class IIa, Level of Evidence C) |

|

❑ Ivabradine should be considered in symptomatic patients with LVEF <_35%, in sinus rhythm and a resting heart rate >_70 b.p.m. who are unable to tolerate

or have contraindications for a beta-blocker to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization and CV death. Patients should also receive an ACE-I (or ARNI) and MRA |

| Soluble guanylate cyclase receptor stimulator: (Class IIb, Level of Evidence B) |

|

❑ Vericiguat may be considered in patients in NYHA class II-IV with worsening HF despite therapy with an ACE-I (or ARNI), a beta-blocker and MRA to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization |

| Hydralazine, isosorbide dinitrate : (Class IIa, Level of Evidence B) |

|

❑ Hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate should be considered in black patients with LVEF <_35% or with an LVEF <45% combined with a dilated left ventricle in NYHA class III-IV despite therapy with an ACE-I (or ARNI), a beta-blocker and an MRA to reduce the risk of HF hospitalization and death.1 |

| Hydralazine, isosorbide dinitrate (Class IIb, Level of Evidence B): |

|

❑ Hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate may be considered in patients with symptomatic HFrEF who unable to tolerate any of an ACE-I, an ARB, or

ARNI (or they are contraindicated) to reduce the risk of death |

| Digoxin: (ClassIIb, Level of Evidence B) |

|

❑ Digoxin may be considered in patients with symptomatic HFrEF in sinus rhythm despite treating with an ACE-I (or ARNI), a beta- blocker and an MRA, to reduce the risk of hospitalization (both all-cause and HF hospitalizations) |

| The above table adopted from 2021 ESC Guideline |

|---|

Management of chronic heart failure

Serial clinical evaluation , titration of Medications

Intensification 2-4 months, (1-4 weeks cycles)

- In the presence of volume overload, adjusting diuretic dose and reevaluation in 1-2 weeks

- In the setting of stable euvolumic status, medications initiation, increase, switch dose and follow-up in 1-2 weeks and checking basic metabolites panel, repeating cycles until no change in clinical status and reached appropriate titration

Assessment of response to medications and cardiac remodeling

- Repeating BNP, pro BNP and basic metabolic panel

- Pepeating ECG, Echocardiography

- Refferal eligible patients to electrophysiology specialist for CRT or ICD implantation

Lack of response, instability

- Referral to advanced heart failure specialist if there are:

- Use of IV inotropes

- NYHA 3B, 4, or persistently high level of natrioretic peptide

- End organ dysfunction

- LVEF ≤ 35%

- Defibrillator shocks

- Hospitalization > 1 day

- Edema despite increase dose of diuretics

- Low blood pressure, high heart rate

- Intolerance to medications

Assessment of response to medications

- Repeating laboratory tests such as NT pro BNP, BNP, electrolytes

- Repeating ECG

- Repeating echocardiography for evaluation of structure, function

- Referral to electrophysiologic for implantation of ICD, CRT in eligible patients

Drugs recommended in all patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- ACE-Is are the first class of drugs that reduce mortality and morbidity in patients with HFrEF and improve symptoms.

- ACEI should be Uptitrated to the maximum tolerated recommended dose.

Beta-blockers

- Beta-blockers can reduce mortality and morbidity in patients with HFrEF, in addition to treatment with an ACE-I and diuretic and also improve symptoms.

- In symptomatic heart failure, ACE-I and beta-blockers can be used in combination.

- Initiation of a beta-blocker before an ACE-I and vice versa are not recommended.[2]

- Beta-blockers should be initiated in clinically stable, euvolaemic, patients at a low dose and gradually titrated to the maximum tolerated dose.

- After stability of hemodynamic in patients admitted with acute heart failure, beta-blockers should be cautiously initiated in hospital

- Use of betablocker in patients with HFrEF with AF was not associated with reduction in mortality or hospital admission.

MRA or Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists

- In all patients with HFrEF, MRAs (spironolactone or eplerenone) are recommended, in addition to an ACE-I and a beta-blocker, to reduce mortality and the risk of heart failure hospitalization.[3]

- MRAs improve symptoms.

- MRAs block receptors that bind aldosterone and also other steroid hormones (corticosteroid and androgen) receptors.

- Eplerenone is more specific for aldosterone blockade and, therefore, causes less gynaecomastia.

- In patients with impaired renal function and in those with serum potassium concentrations >5.0 mmol/L, MRA should be used with causion.

Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor

- In the PARADIGM-HF trial, sacubitril/valsartan, an ARNI, was superior to enalapril in reducing hospitalizations for worsening HF, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality in patients with ambulatory HFrEF with LVEF <_40% (changed to <_35% during the study).[4]

- Patients with elevated plasma NP concentrations, an eGFR >_30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and were able to tolerate enalapril and then sacubitril/valsartan.

- Use of sacubitril/valsartan was associated with improvement in symptoms and quality of life a reduction in the incidence of diabetes requiring insulin treatment,[5]

and a reduction in the decline in eGFR [6]as well as a reduced rate of hyperkalemia[7].

- In addition, the need for loop diuretic reduced while using of sacubitril/valsartan.[8]

- Common side effect of sacubitril/valsartan is symptomatic hypotension as compared to enalapril, but despite developing hypotension, these patients also gained clinical benefits from sacubitril/valsartan therapy.

- The recommendation is that an ACE-I or ARB is replaced by sacubitril/valsartan in ambulatory patients with HFrEF, who remain symptomatic despite optimal treatment.

- Two studies have shown the use of ARNI in hospitalized patients with adequate blood pressure (BP), and an eGFR >_30 mL/min/1.73 m2, without previously treated with ACE-I, was associated with reduced subsequent cardiovascular death or HF hospitalizations.[9][10]

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors

- The result of DAPA-HF trial showed the long-term effects of dapagliflozin (SGLT2 inhibitor) compared to placebo in addition to optimal medical therapy (OMT), on morbidity and mortality in patients with NYHA class II-IV, and had an LVEF <_40%.[11]

- Elevated plasma NT-proBNP and an eGFR >_30 mL/min/1.73 m2 were needed to initiation of therapy.

- Benefits of dapagliflozin in heart failure including:

- Reduction in worsening HF (hospitalization)

- Reduction in cardiovascular death.

- Reduction in all-cause mortality

- Alleviated HF symptomS

- Improvement of physical function and quality of life in patients with symptomatic HFrEF

- Benefits were seen early after the initiation of dapagliflozin.

- Survival benefits were seen in patients with HFrEF with and without diabetes.

- EMPEROR-Reduced trial investigated that empagliflozin reduced the combined primary endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization by 25% in patients with NYHA class II-IV symptoms, and an LVEF <_40% despiteOMT and eGFR >20 mL/min/1.73 m2.

- Reduction in the decline in eGFR and improvement in quality of life among patients receiving empagliflozin were also found.[12]

- Dapagliflozin or empagliflozin are recommended, in addition to OMT with an ACE-I/ARNI, a beta-blocker and an MRA, for patients with HFrEF regardless of diabetes status.

- The need for diuretic may be reduced due to The diuretic/natriuretic properties of SGLT2 inhibitors and reducing congestion.[13]

- The combined SGLT-1 and SGLT-2 inhibitors, sotagliflozin, has also been investigated in patients with diabetes who were hospitalized with HF.[14]

- Side effects of SGLT2 inhibitors including:

- A small reversible reduction in eGFR following initiation

Beta blockers: Third Step in the Management of Heart Failure

Beta blockers reduce the heart rate which lowers the myocardial energy expenditure. They also prolong diastolic filling and lengthen the period of coronary perfusion. Beta blockers can also decrease the toxicity of catecholamines on the myocardium.

Once you have achieved a stable dose of a diuretic and an ACE inhibitor, then one of the three beta blockers that have been associated with improved survival (carvedilol, metoprolol succinate or bisoprolol) can be added and the dose titrated based upon the patient's tolerance. You should avoid beta-blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (pindolol or acebutolol). It should be noted that the 35% reduction in one year mortality observed in meta-analyses of beta-blockers in heart failure was when these drugs were added to ACE inhibitors[15]. There are no direct comparisons of the various beta-blockers, but some data does suggest that carvedilol may improve LVEF more than the others, but it may not be as well tolerated due to its vasodilatory properties. If the patient has been over diuresed, they may not tolerate the addition of a beta blocker.

- Relative contraindications to beta-blocker administration include the following:

- Asthma or bronchospasm

- Hypotension resulting in poor end organ perfusion or symptoms

- Bradycardia or heart block (first degree heart block with a PR interval > 0.24, second degree heart block, third degree heart block

- Peripheral arterial disease with limb ischemia at rest

- Moderate or greater peripheral edema

- Recent intravenous inotropic therapy

Given the potential for hemodynamic decompensation, the initiation of beta-blockers is best undertaken by an individual or center specializing in heart failure management. The patient should be aware of potential side effects, and should be aware that it may take one to three months for the beta-blockers to improve heart failure symptoms. Therapy is initiated with very low doses, and the dose of the beta-blocker should be doubled every two weeks until the target dose is achieved or symptoms prevent further dose escalation.

- Carvedilol: Initial dose 3.125 mg twice daily, target dose 25 to 50 mg twice daily

- Metoprolol succinate: Initial dose 12.5 mg daily, target dose 200 mg daily

- Bisoprolol: Initial dose 1.25 mg daily, target dose 5 to 10 mg daily

Weight gain or peripheral edema that is not responsive to diuresis may require a reduction in the dose of beta-blockers.

Aldosterone Antagonism: Fourth Step in the Management of Heart Failure

An aldosterone antagonist can be added to the regimen of 'select' patients. These selected patients include:

- Class III/IV heart failure and a LVEF <35%

- Class II heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 30%

- Post ST segment elevation MI and a LVEF < 40% who have either symptomatic heart failure or diabetes.

- The serum potassium must be under 5.0 meq/li and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) should be > 30 cc per minute

A requirement for aldosterone antagonist is that the patient's renal function and potassium can be carefully monitored. Eplerenone has fewer endocrine side effects (1%) than spironolactone (10%), but is more costly. A reasonable strategy is to initiate therapy with spironolactone at a dose of 25 to 50 mg daily, and then switch to eplerenone at a dose of 25 to 50 mg daily if endocrine side effects develop.

Risk Factors for the Development of Hyperkalemia on an Aldosterone Antagonist

- Triple therapy with an ACE inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker makes this combination a contraindication

- Higher doses of either an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)

- Hyperkalemia prior to initiation of spironolactone

- Comorbidities such as diabetes and chronic renal insufficiency

- Higher NYHA heart failure class

- Concomitant administration of beta blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or potassium supplements

- A daily dose of Spironolactone greater than 50 mg

The Combination of Hydralazine and a Nitrate: Fifth step in the Management of Heart Failure

The combination of hydralazine and a nitrate (particularly among black patients) can be added if the patient continues to have symptoms on a diuretic, ACE inhibitor (or ARB in the intolerant patient) and a beta blocker. The initial dose is isosorbide dinitrate 20 mg three times a day along with hydralazine 25 mg three times a day. The dose(s) can be increased every 2 to 4 weeks to a target dose of isosorbide dinitrate 40 mg three times a day and hydralazine 75 mg three times a day.

Digoxin: Sixth step in the Management of Heart Failure

Digitalis can strengthen the contractility of the heart and can also be useful to achieve rate control in patients with heart failure who also have atrial fibrillation. In the DIG trial, digoxin reduced the rate of re-hospitalization but did not improve mortality among all patients enrolled in the trial.[16] However, in a retrospective analysis, mortality was reduced in male patients who had digoxin levels between 0.5 and 0.8 ng/mL and was increased in male patients with digoxin levels > 1.2 ng/ml.[17] A similar trend was observed among women patients: there was a trend towards lower mortality at digoxin concentrations between 0.5 to 0.9 ng/ml, but significantly higher mortality at digoxin concentrations > 1.2 ng/ml.[18]

Digoxin should not be used as primary therapy for congestive heart failure. The administration of digoxin is reasonable in patients with NYHA class II-IV heart failure symptoms who have an LVEF of < 40% despite treatment with diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers, and an aldosterone antagonist. Small doses of 0.125 mg per day of digoxin are often effective in maintaining a serum digoxin level between 0.5 and 0.8 ng/ml.

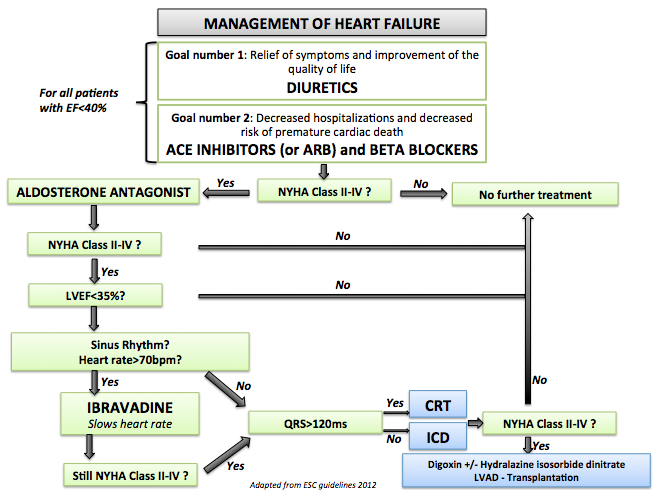

- Shown below is an image that summarizes the steps in the chronic management of patients with heart failure.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland J, Coats A, Crespo-Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam C, Lyon AR, McMurray J, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Francesco Piepoli M, Price S, Rosano G, Ruschitzka F, Kathrine Skibelund A (September 2021). "2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure". Eur Heart J. 42 (36): 3599–3726. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368. PMID 34447992 Check

|pmid=value (help). Vancouver style error: initials (help) - ↑ Willenheimer R, van Veldhuisen DJ, Silke B, Erdmann E, Follath F, Krum H, Ponikowski P, Skene A, van de Ven L, Verkenne P, Lechat P (October 2005). "Effect on survival and hospitalization of initiating treatment for chronic heart failure with bisoprolol followed by enalapril, as compared with the opposite sequence: results of the randomized Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study (CIBIS) III". Circulation. 112 (16): 2426–35. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.582320. PMID 16143696.

- ↑ Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J (September 1999). "The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators". N Engl J Med. 341 (10): 709–17. doi:10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. PMID 10471456.

- ↑ McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR (September 2014). "Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure". N Engl J Med. 371 (11): 993–1004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1409077. PMID 25176015.

- ↑ Seferovic JP, Claggett B, Seidelmann SB, Seely EW, Packer M, Zile MR, Rouleau JL, Swedberg K, Lefkowitz M, Shi VC, Desai AS, McMurray J, Solomon SD (May 2017). "Effect of sacubitril/valsartan versus enalapril on glycaemic control in patients with heart failure and diabetes: a post-hoc analysis from the PARADIGM-HF trial". Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 5 (5): 333–340. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30087-6. PMC 5534167. PMID 28330649. Vancouver style error: initials (help)

- ↑ Damman K, Gori M, Claggett B, Jhund PS, Senni M, Lefkowitz MP, Prescott MF, Shi VC, Rouleau JL, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Packer M, Desai AS, Solomon SD, McMurray J (June 2018). "Renal Effects and Associated Outcomes During Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure". JACC Heart Fail. 6 (6): 489–498. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2018.02.004. PMID 29655829. Vancouver style error: initials (help)

- ↑ Desai AS, Vardeny O, Claggett B, McMurray JJ, Packer M, Swedberg K, Rouleau JL, Zile MR, Lefkowitz M, Shi V, Solomon SD (January 2017). "Reduced Risk of Hyperkalemia During Treatment of Heart Failure With Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists by Use of Sacubitril/Valsartan Compared With Enalapril: A Secondary Analysis of the PARADIGM-HF Trial". JAMA Cardiol. 2 (1): 79–85. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4733. PMID 27842179.

- ↑ Vardeny O, Claggett B, Kachadourian J, Desai AS, Packer M, Rouleau J, Zile MR, Swedberg K, Lefkowitz M, Shi V, McMurray J, Solomon SD (March 2019). "Reduced loop diuretic use in patients taking sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril: the PARADIGM-HF trial". Eur J Heart Fail. 21 (3): 337–341. doi:10.1002/ejhf.1402. PMC 6607492 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 30741494. Vancouver style error: initials (help) - ↑ DeVore AD, Braunwald E, Morrow DA, Duffy CI, Ambrosy AP, Chakraborty H, McCague K, Rocha R, Velazquez EJ (February 2020). "Initiation of Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition After Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: Secondary Analysis of the Open-label Extension of the PIONEER-HF Trial". JAMA Cardiol. 5 (2): 202–207. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4665. PMC 6990764 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 31825471. - ↑ Wachter R, Senni M, Belohlavek J, Straburzynska-Migaj E, Witte KK, Kobalava Z, Fonseca C, Goncalvesova E, Cavusoglu Y, Fernandez A, Chaaban S, Bøhmer E, Pouleur AC, Mueller C, Tribouilloy C, Lonn E, A L Buraiki J, Gniot J, Mozheiko M, Lelonek M, Noè A, Schwende H, Bao W, Butylin D, Pascual-Figal D (August 2019). "Initiation of sacubitril/valsartan in haemodynamically stabilised heart failure patients in hospital or early after discharge: primary results of the randomised TRANSITION study". Eur J Heart Fail. 21 (8): 998–1007. doi:10.1002/ejhf.1498. PMID 31134724. Vancouver style error: missing comma (help)

- ↑ McMurray J, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, Ponikowski P, Sabatine MS, Anand IS, Bělohlávek J, Böhm M, Chiang CE, Chopra VK, de Boer RA, Desai AS, Diez M, Drozdz J, Dukát A, Ge J, Howlett JG, Katova T, Kitakaze M, Ljungman C, Merkely B, Nicolau JC, O'Meara E, Petrie MC, Vinh PN, Schou M, Tereshchenko S, Verma S, Held C, DeMets DL, Docherty KF, Jhund PS, Bengtsson O, Sjöstrand M, Langkilde AM (November 2019). "Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction". N Engl J Med. 381 (21): 1995–2008. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911303. PMID 31535829. Vancouver style error: initials (help)

- ↑ Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Januzzi J, Verma S, Tsutsui H, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Kimura K, Schnee J, Zeller C, Cotton D, Bocchi E, Böhm M, Choi DJ, Chopra V, Chuquiure E, Giannetti N, Janssens S, Zhang J, Gonzalez Juanatey JR, Kaul S, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Merkely B, Nicholls SJ, Perrone S, Pina I, Ponikowski P, Sattar N, Senni M, Seronde MF, Spinar J, Squire I, Taddei S, Wanner C, Zannad F (October 2020). "Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure". N Engl J Med. 383 (15): 1413–1424. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022190. PMID 32865377 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Jackson AM, Dewan P, Anand IS, Bělohlávek J, Bengtsson O, de Boer RA, Böhm M, Boulton DW, Chopra VK, DeMets DL, Docherty KF, Dukát A, Greasley PJ, Howlett JG, Inzucchi SE, Katova T, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Langkilde AM, Lindholm D, Ljungman C, Martinez FA, O'Meara E, Sabatine MS, Sjöstrand M, Solomon SD, Tereshchenko S, Verma S, Jhund PS, McMurray J (September 2020). "Dapagliflozin and Diuretic Use in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction in DAPA-HF". Circulation. 142 (11): 1040–1054. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047077. PMC 7664959 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32673497 Check|pmid=value (help). Vancouver style error: initials (help) - ↑ Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Steg PG, Cannon CP, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Lewis JB, Riddle MC, Voors AA, Metra M, Lund LH, Komajda M, Testani JM, Wilcox CS, Ponikowski P, Lopes RD, Verma S, Lapuerta P, Pitt B (January 2021). "Sotagliflozin in Patients with Diabetes and Recent Worsening Heart Failure". N Engl J Med. 384 (2): 117–128. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2030183. PMID 33200892 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Brophy JM, Joseph L, Rouleau JL (2001). "Beta-blockers in congestive heart failure. A Bayesian meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 134 (7): 550–60. PMID 11281737. Retrieved 2013-04-28. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ "The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. The Digitalis Investigation Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (8): 525–33. 1997. doi:10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. PMID 9036306. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Rathore SS, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Bristow MR, Krumholz HM (2003). "Association of serum digoxin concentration and outcomes in patients with heart failure". JAMA : the Journal of the American Medical Association. 289 (7): 871–8. PMID 12588271. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Adams KF, Patterson JH, Gattis WA, O'Connor CM, Lee CR, Schwartz TA, Gheorghiade M (2005). "Relationship of serum digoxin concentration to mortality and morbidity in women in the digitalis investigation group trial: a retrospective analysis". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 46 (3): 497–504. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.091. PMID 16053964. Retrieved 2013-04-29. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)