Neurofibromatosis

| Neurofibromatosis | |

| |

|---|---|

| Back of an elderly woman with Neurofibromatosis. | |

| ICD-10 | Q85.0 |

| ICD-9 | 237.7 |

| ICD-O: | 9540/0 |

| MeSH | D017253 |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Kiran Singh, M.D. [2]

Overview

Neurofibromatosis is a genetically-inherited disease in which nerve tissue grows tumors (e.g. neurofibromas) that may be harmless or may cause serious damage by compressing nerves and other tissues. The disorder affects all neural crest cells (Schwann cells, melanocytes, endoneurial fibroblasts). Cellular elements from these cell types proliferate excessively throughout the body forming tumors and the melanocytes function abnormally resulting in disordered skin pigmentation.The tumors may cause bumps under the skin, colored spots, skeletal problems, pressure on spinal nerve roots, and other neurological problems. [1]

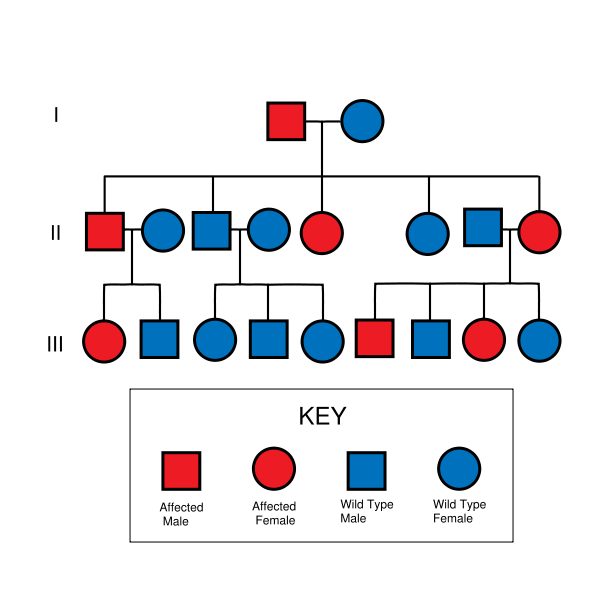

Neurofibromatosis is autosomal dominant, which means that it affects males and females equally and is dominant (only one copy of the affected gene is needed to get the disorder). Therefore, if only one parent has neurofibromatosis, his or her children have a 50% chance of developing the condition as well. Disease severity in affected individuals, however, can vary (this is called variable expressivity). Moreover, in around half of cases there is no other affected family member because a new mutation has occurred.

Differential Diagnosis

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1

History

Neurofibromatosis was discovered in 1882 by the German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen. He wrote on it and published it in Hämochromatose, Tageblatt der Naturforschenden Versammlung.[2]

Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man, was once considered to have been affected with either elephantiasis or neurofibromatosis type I. However, it is now generally believed that Merrick suffered from the very rare Proteus syndrome. This however has given rise to the common misconception that Neurofibromatosis and "Elephant Man Disease" are one and the same.

Mechanism

Neurofibromatosis affects humans on a genetic level, meaning that it either destroys, or renders defective a specific gene. NF-1

- The gene that NF-1 affects is large, on band 17q11.2. It encodes for a protein called neurofibromin, otherwise known as "the tumor suppressor" protein. Neurofibromatosis alters or weakens this protein, rapid, radical growth of cells is allowed all over the body, especially around the nervous system. This leads to the normal symptoms for neurofibromatosis - clumpings of these tumors, called neurofibromas and schwannomas.

- Less is known about the NF-2 linked gene. However, it is on band 22q1 and also codes for a protein, most likely one similar to NF-1's.

Effects

People with Neurofibromatosis can be affected in many different ways.

- There is a high incidence of learning disabilities in people with NF. It is believed that at least 50% of people with NF have learning disabilities of some type.

- increased chances of development of petit mal epilepsy (a Partial absence seizure disorder)

- The tumors that occur can grow anywhere a nerve is present. This means that:

- They can grow in places that are very visible to people that a patient may encounter on the street.

- The tumors can also grow in places that can cause other medical issues that may require them to be removed for the patient's safety.

- Affected individuals may need multiple surgeries, depending on where the tumors are located.

Related disorders

Neurofibromatosis is considered a member of the neurocutaneous syndromes (phakomatoses). In addition to the types of neurofibromatosis, the phakomatoses also include tuberous sclerosis, Sturge-Weber syndrome and von Hippel-Lindau disease. This grouping is an artifact of an earlier time in medicine, before the distinct genetic basis of each of these diseases was understood.

Types

- Neurofibromatosis type I Incidence is 1:3,500 live births

- Neurofibromatosis type II ((central neurofibromatosis or "MISME Syndrome"). Incidence is 1:25,000

- Neurofibromatosis type 3

- Neurofibromatosis type 4

- Schwannomatosis. Incidence is unknown but thought to be 1:40,000

Diagnostic Criteria

Neurofibromatosis type 1

Neurofibromatosis type 1 - mutation of neurofibromin chromosome 17q11.2. The diagnosis of NF1 is made if any two of the following seven criteria are met:

- Two or more neurofibromas on the skin or under the skin or one plexiform neurofibroma (a large cluster of tumors involving multiple nerves); Neurofibromas are the subcutaneous lumps that are characteristic of the disease and increase in number with age.

- Freckling of the groin or the axilla (arm pit).

- Café au lait spots (pigmented birthmarks). Six or more measuring 5 mm in greatest diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals

- Skeletal abnormalities, such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of the cortex of the long bones of the body (i.e. bones of the leg, potentially resulting in bowing of the legs)

- Lisch nodules (hamartomas of iris), freckling in the iris.

- Tumors on the optic nerve, also known as an optic glioma

- A first-degree relative with a diagnosis of NF1

Skin

Trunk

-

Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

Face

-

Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

Neurofibromatosis type 2

Neurofibromatosis type 2 - mutation of merlin chromosome 22q12

- bilateral tumors, acoustic neuromas on the vestibulocochlear nerve, located on the eighth cranial nerve leading to hearing loss

- In fact, the hallmark of NF 2 is hearing loss due to acoustic neuromas around the age of twenty

- the tumors may cause:

- headache

- balance problems, and Vertigo

- facial weakness/paralysis

- patients with NF2 may also develop other brain tumors, as well as spinal tumors

- Deafness and Tinnitus

- Any relative with NF-2, diagnosed or not

Schwannomatosis

Schwannomatosis - gene involved has yet to be identified

- Multiple Schwannomas occur.

- The Schwannomas develop on cranial, spinal and peripheral nerves.

- Chronic pain, and sometimes numbness, tingling and weakness.

- About 1/3 of patients have segmental Schwannomatosis, which means that the Schwannomas are limited to a single part of the body, such as an arm, a leg or the spine.

- Unlike the other forms of NF, the Schwannomas do not develop on vestibular nerves, and as a result, no loss of hearing is associated with Schwannomatosis.

- Patients with Schwannomatosis do not have learning disabilities related to the disease.

One must keep in mind, however, that neurofibromatosis can't occur in or affect any of the organ systems, whether that entails simply compressing them (from tumor growth) or in fact altering the organs in some fundamental way. This disparity in the disease is one of many factors that makes it difficult to diagnose, and eventually find a prognosis for.

Physical Examination

Skin

Trunk

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis.With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

Face

-

Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.

-

Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

Extremity

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

Face

-

.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]

Genetics and Hereditability

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is due to mutation on chromosome 17q11.2 , the gene product being Neurofibromin ( a GTPase activating enzyme).[4]

Neurofibromatosis type 2 is due to mutation on chromosome 22q , the gene product is Merlin, a cytoskeletal protein.

Both NF1 and NF2 are autosomal dominant disorders, meaning that only one copy of the mutated gene need be inherited to pass the disorder. A child of a parent with NF1 or NF2 and an unaffected parent will have a 50% chance of inheriting the disorder.

Complicating the question of heritability is the distinction between genotype and phenotype, that is, between the genetics and the actual manifestation of the disorder.

In the case of NF1, no clear links between genotype and phenotype have been found, and the severity and specific nature of the symptoms may vary widely among family members with the disorder.[5] In the case of NF2, however, manifestations are similar among family members; a strong genotype-phenotype correlation is believed to exist (ibid).

Both NF1 and NF2 can also appear to be spontaneous mutation, with no family history. These cases account for about one half of neurofibromatosis cases (ibid).

Similar to polydactyly, although NF is a dominant mutation, it is not prevalent in society. Neurofibromatosis-1 is found in approximately 1 in 2,500-3,000 live births (carrier incidence 0.0004, gene frequency 0.0002). NF-2 is less common, having one case in 50,000-120,000 live births.[6]

Diagnosis

NF1 is the more common type of the neurofibromatoses. In diagnosing NF1, a physician looks for changes in skin appearance, tumors, or bone abnormalities, and/or a parent, sibling, or child with NF1. Symptoms of NF1, particularly those on the skin, are often evident at birth or during infancy and almost always by the time a child is about 10 years old. NF2 is less common. NF2 is characterized by bilateral (occurring on both sides of the body) tumors on the eighth cranial nerve. The tumors cause pressure damage to neighboring nerves. To determine whether an individual has NF2, a physician looks for bilateral eighth nerve tumors and similar signs and symptoms in a parent, sibling, or child. Affected individuals may notice hearing loss as early as the teen years. Other early symptoms may include tinnitus (ringing noise in the ear) and poor balance. Headache, facial pain, or facial numbness, caused by pressure from the tumors, may also occur.

Treatment

Treatments for both NF1 and NF2 are presently aimed at controlling symptoms. Surgery can help some NF1 bone malformations and remove painful or disfiguring tumors; however, there is a chance that the tumors may grow back and in greater numbers. In the rare instances when tumors become malignant (3 to 5 percent of all cases), treatment may include surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy. [7]

For NF2, improved diagnostic technologies, such as MRI, can reveal tumors as small as a few millimeters in diameter, thus allowing early treatment.

Surgery to remove tumors completely is one option but may result in hearing loss. Other options include partial removal of tumors, radiation, and if the tumors are not progressing rapidly, the conservative approach of watchful waiting. Genetic testing is available for families with documented cases of NF1 and NF2.

New (spontaneous) mutations cannot be confirmed genetically. Prenatal diagnosis of familial NF1 or NF2 is also possible utilizing amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling procedures.

Prognosis

In most cases, symptoms of NF1 are mild, and patients live normal and productive lives. In some cases, however, NF1 can be severely debilitating. In some cases of NF2, the damage to nearby vital structures, such as other cranial nerves and the brainstem, can be life-threatening.

Case Examples

Case #1

Clinical Summary

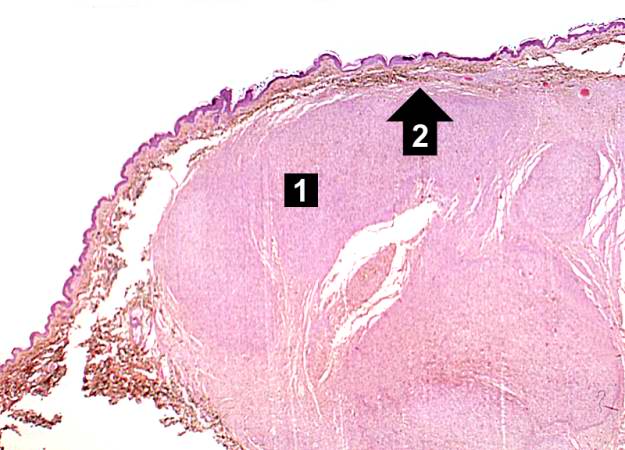

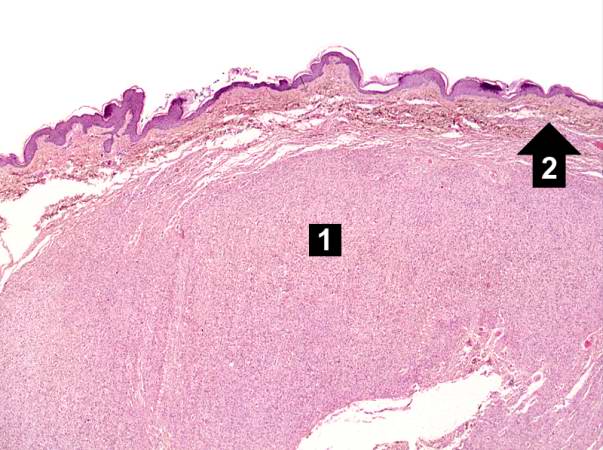

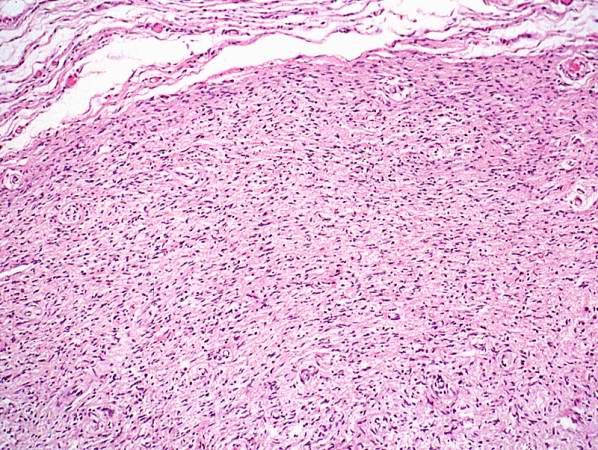

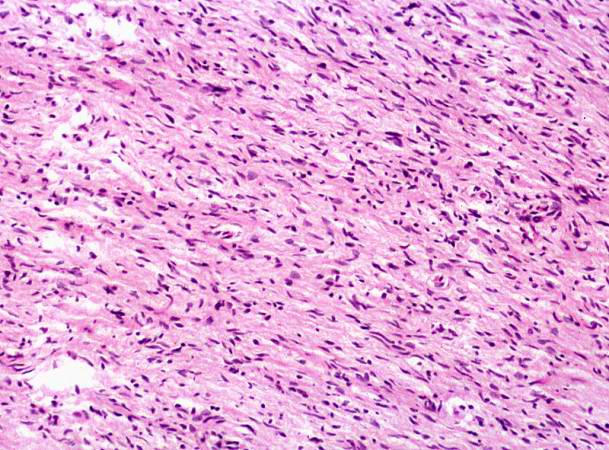

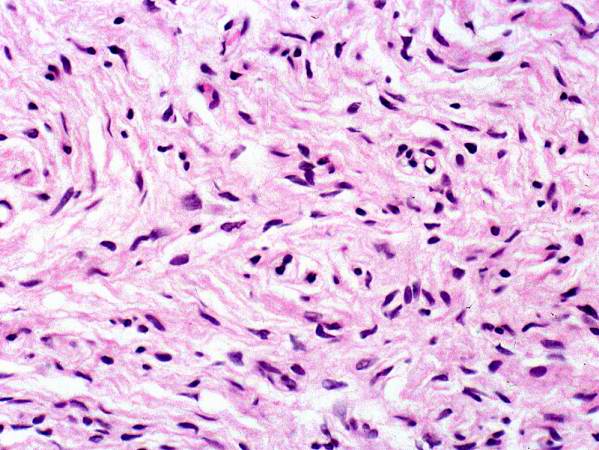

This 45-year-old divorced white male came to the emergency room with severe hepatic cirrhosis and aspiration pneumonia. Shortly after admission he developed cardiac arrhythmias and died. Significant past history included alcohol abuse, cirrhosis, and neurofibromatosis. He had no family history of neurofibromatosis, but his condition was diagnosed at age 17 when he developed neurofibromas along the lateral chest wall. There was no history of continued follow-up after this initial diagnosis.

Autopsy Findings

The patient was covered with variably sized subcutaneous nodules ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter. Other significant findings included micronodular hepatic cirrhosis (liver weight: 1760 grams), ascites (500 ml), and splenomegaly (weight: 260 grams).

Histopathological Findings

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.merck.com/mmhe/sec06/ch088/ch088d.html Merck Manual Home Edition, "Neurofibromatosis"

- ↑ Template:WhoNamedIt

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 3.29 3.30 3.31 3.32 3.33 3.34 3.35 3.36 3.37 3.38 3.39 3.40 3.41 3.42 3.43 3.44 3.45 3.46 3.47 3.48 3.49 3.50 3.51 3.52 3.53 "Dermatology Atlas".

- ↑ Fauci, et al Harrison's Principle of Internal Medicine 16th Ed. p 2453

- ↑ Korf, Bruce E. and Allan E. Rubenstein. 2005. Neurofibromatosis: A Handbook for Patients, Families, and Health Care Professionals.

- ↑ Jennifer R. Kam, Jan. 2007

- ↑ Neurofibromatosis. JAMA patient page, Vol. 300 No. 3, July 16, 2008.

External links

- Information page from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (part of the National Institutes of Health in the United States) -- this Wikipedia article is based largely on this NINDS information page

- Vestibular Schwannoma (Acoustic Neuroma) and Neurofibromatosis at National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

- Template:DMOZ

- Home Page of the Children's Tumor Foundation (a non-profit organization working towards a cure for Neurofibromatosis in the United States)

- Home page from NF Inc (a non-profit organization working towards Neurofibromatosis patient support in the United States)

- Home Page of the the Reggie Bibbs website (a non-profit organization working providing patient education, awareness and support of Neurofibromatosis in the United States)

Template:Nervous tissue tumors

de:Neurofibromatose it:Neurofibromatosi lt:Neurofibromatozė hu:Neurofibromatózis nl:Neurofibromatose no:Nevrofibromatose sv:Neurofibromatos

![Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/4/4f/Segmental_neurofibromatosis01.jpg)

![Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/7/73/Segmental_neurofibromatosis02.jpg)

![Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/f/ff/Segmental_neurofibromatosis03.jpg)

![Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/6/67/Segmental_neurofibromatosis04.jpg)

![Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/6/6d/Segmental_neurofibromatosis05.jpg)

![Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/5/5d/Segmental_neurofibromatosis06.jpg)

![Segmental neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/e/ef/Segmental_neurofibromatosis07.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/d/d2/Neurofibromatosis01.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/9/9d/Neurofibromatosis02.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/a/ab/Neurofibromatosis05.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/7/79/Neurofibromatosis06.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis.With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/a/ad/Neurofibromatosis07.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/5/5b/Neurofibromatosis08.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/1/16/Neurofibromatosis09.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/e/ee/Neurofibromatosis10.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/1/1b/Neurofibromatosis11.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/0/0a/Neurofibromatosis12.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/8/80/Neurofibromatosis13.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/0/0b/Neurofibromatosis14.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/d/d2/Neurofibromatosis15.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/5/54/Neurofibromatosis16.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/0/07/Neurofibromatosis19.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/3/32/Neurofibromatosis22.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/e/ec/Neurofibromatosis25.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/6/64/Neurofibromatosis26.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/a/a6/Neurofibromatosis27.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/a/a0/Neurofibromatosis32.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/6/62/Neurofibromatosis38.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/6/66/Neurofibromatosis40.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/a/a4/Neurofibromatosis41.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/7/71/Neurofibromatosis42.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/4/45/Neurofibromatosis44.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/c/c6/Neurofibromatosis45.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/a/a0/Neurofibromatosis47.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/1/18/Neurofibromatosis48.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/5/5b/Neurofibromatosis49.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/1/18/Neurofibromatosis50.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis. With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/2/23/Neurofibromatosis51.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/7/79/Neurofibromatosis17.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/f/f3/Neurofibromatosis18.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/a/a6/Neurofibromatosis29.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/1/1c/Neurofibromatosis31.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/c/cd/Neurofibromatosis34.jpg)

![Neurofibromatosis With permission from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/6/64/Neurofibromatosis43.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/5/56/Neurofibromatosis04.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/5/57/Neurofibromatosis23.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/2/2e/Neurofibromatosis24.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/1/1e/Neurofibromatosis28.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/7/7c/Neurofibromatosis35.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/8/81/Neurofibromatosis36.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/d/d9/Neurofibromatosis37.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/e/e5/Neurofibromatosis39.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/e/ee/Neurofibromatosis46.jpg)

![.Neurofibromatosis Adapted from Dermatology Atlas.[3]](/images/6/66/Neurofibromatosis03.jpg)