Mononucleosis laboratory findings

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

|

Mononucleosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Mononucleosis laboratory findings On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Mononucleosis laboratory findings |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Mononucleosis laboratory findings |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

In most cases of infectious mononucleosis, the clinical diagnosis can be made from the characteristic triad of fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy lasting for 1 to 4 weeks.

Laboratory Findings

- Serologic test results include:

- A normal to moderately elevated white blood cell count

- An increased total number of lymphocytes

- Greater than 10% atypical lymphocytes

- A positive reaction to a mono spot test

- In patients with symptoms compatible with infectious mononucleosis, a positive Paul-Bunnell heterophile antibody test result is diagnostic, and no further testing is necessary.

- Moderate-to-high levels of heterophile antibodies are seen during the first month of illness and decrease rapidly after week 4.

- False-positive results may be found in a small number of patients, and false-negative results may be obtained in 10% to 15% of patients, primarily in children younger than 10 years of age.

- When mono spot or heterophile test results are negative, additional laboratory testing may be needed to differentiate EBV infections from a mononucleosis-like illness induced by cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, or toxoplasma gondii.

- Direct detection of EBV in blood or lymphoid tissues is a research tool and is not available for routine diagnosis.

- Instead, serologic testing is the method of choice for diagnosing primary infection.

- Epstein-Barr virus specific antibody testing may be used for people with suspected mononucleosis who have heterophile antibody test results that are negative. It can also be used to test for atypical cases of mononucleosis or in young children who are suspected of having mononucleosis.

- Epstein-Barr virus antigen by immunofluorescence

- Epstein-Barr virus antibody titers to distinguish acute infection from past infection with EBV. Antibodies to several antigen complexes may be measured, which include: early antigen, viral capsid antigen and epstein barr nuclear antigen.

Complete Blood Count with Differential

- Normal to moderately elevated white blood cell count, particularly the number of lymphocytes is observed with a total white blood count increased to 10,000-20,000 per cubic millimeter.

- Elevation of the lymphocycte count above 35% of the total white cell count has a specificity of 100% and a sensitivity of 90% for the detection of glandular fever.[1]

- The presence of atypical lymphocytes (often recorded by automated blood analyser machines as an increase in the monocycte count) is characteristic of EBV infection.

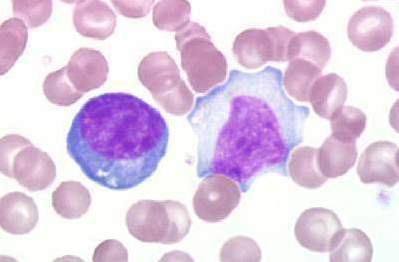

Peripheral Blood Smear

- The laboratory hallmark of the disease is the presence of atypical lymphocytes (a type of mononuclear cell) on the peripheral blood smear.

- Atypical lymphocytosis is present in approximately 75% of patients infected with mononucleosis.

- Greater than 10% atypical lymphocytes is diagnostic of mononucleosis.

Liver Function Tests

- Liver function tests may show a moderate elevation of liver enzyme levels in nearly 90% of patients infected with mononucleosis in contrast to the significant increase in liver enzyme levels observed in patients with viral hepatitis.

Serology

Mononucleosis causes so-called heterophile antibodies, which cause agglutination of non-human red blood cells, to appear in the patient's blood.

Heterophile Antibody (AB)

- ABs reactive against sheep (and horse) red bloood cells

- Present in 90-95% of patients infected with mononucleosis

- False negative in 10-15% during 1st week of illness and in young children

- Detectable up to 1 year after initial symptoms

- Heterophile titer or monospot is diagnostic test of choice [2][3]

Monospot Test

- The monospot is a non-specific test that screens for mononucleosis by looking for these heterophile antibodies.

- The spot test may be negative in the first week, so negative tests are often repeated at a later date.

- Since the spot test is usually negative in children less than 6-8 years old, an EBV serology test should be done on them if mononucleosis is suspected.

- An older test for heterophile antibodies is the Paul-Bunnell test, in which the patient's serum is mixed with sheep red blood cells and checked for agglutination of these cells.

Test Results: Interpretation

- The qualitative heterophile antibody test (Monospot) gives either a positive or negative result. The monospot test is 70-92% sensitive and 96-100% specific.[4] This test is commercially-available, takes minutes to perform and provides rapid results.

- Presence of positive mono test with an increased number of white blood cells, reactive lymphocytes, and symptoms of mononucleosis, is diagnostic of infectious mononucleosis.

- If symptoms and reactive lymphocytes are present but the mono test is negative, then it may be too early to detect the heterophile antibodies or the affected patient may be in the small number of people who do not make heterophile antibodies.

- Other EBV antibodies and/or a repeat mono test may be performed to help confirm or rule out the mononucleosis diagnosis.[5]

- Confirmation of the exact etiology can be obtained through tests to detect specific antibodies to the causative viruses.

Electrolyte and Biomarker Studies

Indication: Only in Atypical or Heterophile Negative Cases

- Laboratory tests for EBV are for the most part accurate and specific. Because the antibody response in primary EBV infection appears to be quite rapid, in most cases testing paired acute- and convalescent-phase serum samples will not demonstrate a significant change in antibody level.

- Effective laboratory diagnosis can be made on a single acute-phase serum sample by testing for antibodies to several EBV-associated antigens simultaneously. In most cases, a distinction can be made as to whether a person is susceptible to EBV, has had a recent infection, has had infection in the past, or has a reactivated EBV infection.

- Antibodies to several antigen complexes that are measured include:

- Viral capsid antigen,

- The early antigen, and

- The EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA).

- In addition, differentiation of immunoglobulin G and M subclasses to the viral capsid antigen can often be helpful for confirmation.

- When the mono spot test is negative, the optimal combination of EBV serologic testing consists of the antibody titration of four markers:

- IgM to the viral capsid antigen appears early in infection and disappears within 4 to 6 weeks. IgG to the viral capsid antigen appears in the acute phase, peaks at 2 to 4 weeks after onset, declines slightly, and then persists for life. IgG to the early antigen appears in the acute phase and generally falls to undetectable levels after 3 to 6 months. In many people, detection of antibody to the early antigen is a sign of active infection, but 20% of healthy people may have this antibody for years.

- Antibody to EBNA determined by the standard immunofluorescent test is not seen in the acute phase, but slowly appears 2 to 4 months after onset, and persists for life. This is not true for some EBNA enzyme immunoassays, which detect antibody within a few weeks of onset.

- Finally, even when EBV antibody tests, such as the early antigen test, suggest that reactivated infection is present, this result does not necessarily indicate that a patient's current medical condition is caused by EBV infection. A number of healthy people with no symptoms have antibodies to the EBV early antigen for years after their initial EBV infection.

| Antibody (AB) | Time of appearance | Persistence | % Patients present |

| Viral capsid antigen-IgM (VCA-IgM) | At clinical presentation | 1-3 months | 100% |

| Viral capsid antigen-IgG (VCA-IgG) | At clinical presentation | Lifelong | 100% |

| Early antigen-IgG (EA IgG) | Peak 3-4 weeks after onset | 3-6 months | 70% |

| EBV nuclear antigen-IgG (EBNA IgG) | 6-12 weeks after onset | Lifelong | 100% |

Diagnosis Summary: Based on the Stage of Infection

Primary Infection

- Primary EBV infection is indicated if IgM antibody to the viral capsid antigen is present and antibody to EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA), is absent.

- A rising or high IgG antibody to the viral capsid antigen and negative antibody to EBV nuclear antigen after at least 4 weeks of illness is also strongly suggestive of primary infection.

- In addition, 80% of patients with active EBV infection produce antibody to early antigen.

Past Infection

- If antibodies to both the viral capsid antigen and EBV nuclear antigen are present, then past infection (from 4 to 6 months to years earlier) is indicated.

- Since 95% of adults have been infected with EBV, most adults will show antibodies to EBV from infection years earlier.

- High or elevated antibody levels may be present for years and are not diagnostic of recent infection.

Reactivation

- In the presence of antibodies to EBV nuclear antigen, an elevation of antibodies to early antigen suggests reactivation.

- However, when EBV antibody to the early antigen test is present, this result does not automatically indicate that a patient's current medical condition is caused by EBV.

- A number of healthy people with no symptoms have antibodies to the EBV early antigen for years after their initial EBV infection. Many times reactivation occurs subclinically.

Chronic EBV Infection

- Reliable laboratory evidence for continued active EBV infection is very seldom found in patients who have been ill for more than 4 months.

- When the illness lasts more than 6 months, it should be investigated to see if other causes of chronic illness or chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) are present.

| Antibody (AB) | Time of appearance | Persistence | % Patients present |

| Viral capsid antigen-IgM (VCA-IgM) | At clinical presentation | 1-3 months | 100% |

| Viral capsid antigen-IgG (VCA-IgG) | At clinical presentation | Lifelong | 100% |

| Early antigen-IgG (EA IgG) | Peak 3-4 weeks after onset | 3-6 months | 70% |

| EBV nuclear antigen-IgG (EBNA IgG) | 6-12 weeks after onset | Lifelong | 100% |

References

- ↑ Wolf DM, Friedrichs I, Toma AG (2007). "Lymphocyte-white blood cell count ratio: a quickly available screening tool to differentiate acute purulent tonsillitis from glandular fever". Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 133 (1): 61–4. doi:10.1001/archotol.133.1.61. PMID 17224526.

- ↑ Evans AS, Niederman JC, Cenabre LC, West B, Richards VA (1975). "A prospective evaluation of heterophile and Epstein-Barr virus-specific IgM antibody tests in clinical and subclinical infectious mononucleosis: Specificity and sensitivity of the tests and persistence of antibody". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 132 (5): 546–54. PMID 171321. Retrieved 2012-02-28. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Feorino PM, Dye LA, Humphrey DD (1971). "Comparison of diagnostic tests for infectious mononucleosis". Journal of the American College Health Association. 19 (3): 190–3. PMID 5101085. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Elgh F, Linderholm M (1996). "Evaluation of six commercially available kits using purified heterophile antigen for the rapid diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis compared with Epstein-Barr virus-specific serology". Clin Diagn Virol. 7 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1016/S0928-0197(96)00245-0. PMID 9077426.

- ↑ "Mono Test: The Test". Lab Tests Online.