Macrocytic anemia laboratory findings

|

Macrocytic anemia Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Macrocytic anemia laboratory findings On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Macrocytic anemia laboratory findings |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Macrocytic anemia laboratory findings |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Shyam Patel [2];Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Omer Kamal, M.D.[3] Amandeep Singh M.D.[4]

Overview

The lab findings include measuring levels of vitamin B12, folate, methylmalonic acid, and homocysteine. Peripheral blood smear is also helpful.

Laboratory Findings

The following laboratory findings can be found in macrocytic anemia: [1][2][3][4][5]

- Measurement of homocysteine and methylmalonic acid can help confirm and differentiate from folate deficiency.

- Both homocysteine and methylmalonic acid are elevated in vitamin B12 deficiency while only homocysteine is elevated in folate deficiency.

- If pernicious anemia is based on low serum level, anti-intrinsic factor antibodies are confirmatory but only present in 50%.

- Anti-parietal cell Abs are more sensitive (90%) but less specific.

Schilling Test [6][7][8][9][10]

Dietary vitamin B12 is bound to factors that are cleaved off by acid leaving vitamin B12 free to bind to R factors secreted by the saliva and gastric juice. Vitamin B12 bound to salivary R factor is not absorbed, but instead requires the alkaline pancreatic secretions and proteases in the duodenum to be freed from R factor. Free vitamin B12 can then bind to intrinsic factor where it is transported to the ileum where a specific receptor then takes up the complex. Therefore, normal vitamin B12 absorption and action are dependent of 5 things:

- Dietary intake (meat and milk)

- Acid in the stomach

- Pancreatic secretions

- Secretion of IF by Gastric parietal cells

- An ileum that can absorb the IF-B12 complex

The Schilling test is designed to test the different components of this system.

- First, 1mg IM B12 is given to saturate transcobalamin.

- Radiolabeled B12 is then given orally.

- If it can be absorbed, then >9% will be excreted in the urine in 24 hours and the rest is eliminated in the feces undetected.

- Renal insufficiency causes a falsely low level.

- It may be spuriously normal in patients without gastrectomy.

- Acid is required to free dietary B12 from binding factors.

- Radiolabeled vitamin B12 is not bound to these factors. Therefore, persons with impaired acid and pepsin production can absorb too little dietary B12, but will absorb free vitamin B12 normally.

Part II of the Schilling test is administering radiolabeled vitamin B12 with IF to see if the problem corrects. This should differentiate pernicious anemia from those with intestinal malabsorption. Vitamin B12 deficiency affects the intestinal mucosal cells and causes malabsorption. Therefore, Part II should only be done 4 weeks after replacement, giving the mucosa time to regenerate in pernicious anemia.

- If Part II is abnormal, Part III is basically a repeat of Part I after a course of antibiotics/vermicides.

- If this is abnormal, an malabsorptive cause is implicated.

Analysis [6][7][8][9][10]

The Schilling test was performed in the past to determine the nature of the vitamin B12 deficiency, but due to the lack of available radioactive B12, it is now largely a historical artifact. [[Vitamin B12|Vitamin BTemplate:Ssub]] is a necessary prosthetic group to the enzyme methylmalonyl-coenzyme A mutase. B12 deficiency leads to dysfunction of this enzyme and a buildup of its substrate, methylmalonic acid, the elevated level of which can be detected in the urine and blood. Since the level of methylmalonic acid is not elevated in folic acid deficiency, this test provides a one tool in differentiating the two. However, since the test for elevated methylmalonic acid is not specific enough, the gold standard for the diagnosis of B12 deficiency is a low blood level of B12. Unlike the Shilling test, which often included B12 with intrinsic factor, a low level of blood B12 gives no indication as to the etiology of the low B12, which may result from a number of mechanisms.

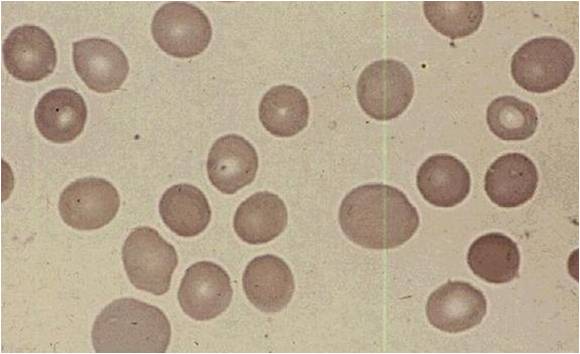

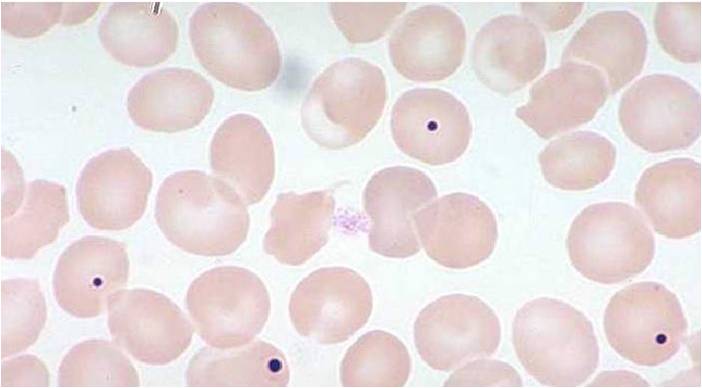

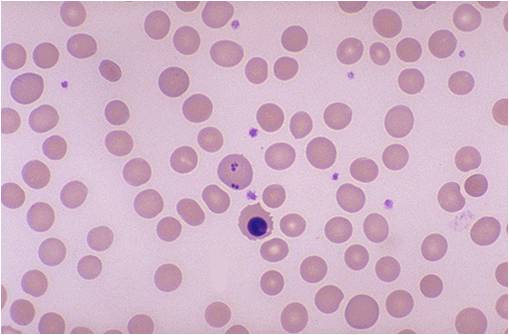

Hematological findings[11][12][13][13][14][15]

MCV is often >110. Hematocrit can often be as low as 15. Elevated LDH and bilirubin are seen since dyserythopoesis leads to destruction of >90% of RBC precursors. Hypersegmentation of PMNs is quite sensitive (>5% with 5 or more lobes or >1% with 6 lobes). Reticulocyte, WBC and platelets are low to normal. In one series of patients with B12 deficiency, 64% had a MCV greater than 100, and only 29% had anemia. In general the blood film can point towards vitamin deficiency:

- Decreased red blood cell (RBC) count and hemoglobin levels

- Increased mean corpuscular volume (MCV >95 fl often >110) and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH)

- The reticulocyte count is normal.

- The platelet count may be reduced.

- Neutrophil granulocytes may show multisegmented nuclei ("senile neutrophil"). This is thought to be due to decreased production and a compensatory prolonged lifespan for circulating neutrophils.

- Anisocytosis (increased variation in RBC size) and poikilocytosis (abnormally shaped RBCs).

- Macrocytes (larger than normal RBCs) are present.

- Ovalocytes (oval shaped RBCs) are present.

- Bone marrow (not normally checked in a patient suspected of megaloblastic anemia) shows megaloblastic hyperplasia.

- Howell-Jolly bodies (chromosomal remnant) also present.

Blood chemistries will also show:

- Increased homocysteine and methylmalonic acid in B12 deficiency

- Increased homocysteine in folate defiency

References

- ↑ Annibale B, Lahner E, Fave GD (December 2011). "Diagnosis and management of pernicious anemia". Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 13 (6): 518–24. doi:10.1007/s11894-011-0225-5. PMID 21947876.

- ↑ Morris MS, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Selhub J (January 2007). "Folate and vitamin B-12 status in relation to anemia, macrocytosis, and cognitive impairment in older Americans in the age of folic acid fortification". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85 (1): 193–200. doi:10.1093/ajcn/85.1.193. PMC 1828842. PMID 17209196.

- ↑ GLASS GB, BOYD LJ, GELLIN GA (February 1955). "Surface scintillation measurements in humans of the uptake of parenterally administered radioactive vitamin B12". Blood. 10 (2): 95–114. PMID 13230162.

- ↑ Herrmann W, Obeid R (October 2008). "Causes and early diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 105 (40): 680–5. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2008.0680. PMC 2696961. PMID 19623286.

- ↑ Lahner E, Annibale B (November 2009). "Pernicious anemia: new insights from a gastroenterological point of view". World J. Gastroenterol. 15 (41): 5121–8. PMC 2773890. PMID 19891010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Brugge WR, Goff JS, Allen NC, Podell ER, Allen RH (May 1980). "Development of a dual label Schilling test for pancreatic exocrine function based on the differential absorption of cobalamin bound to intrinsic factor and R protein". Gastroenterology. 78 (5 Pt 1): 937–49. PMID 7380200.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Oh R, Brown DL (March 2003). "Vitamin B12 deficiency". Am Fam Physician. 67 (5): 979–86. PMID 12643357.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Harriman GR, Smith PD, Horne MK, Fox CH, Koenig S, Lack EE, Lane HC, Fauci AS (September 1989). "Vitamin B12 malabsorption in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome". Arch. Intern. Med. 149 (9): 2039–41. PMID 2774781.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Doscherholmen A, Silvis S, McMahon J (October 1983). "Dual isotope Schilling test for measuring absorption of food-bound and free vitamin B12 simultaneously". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 80 (4): 490–5. PMID 6684880.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Streeter AM, Shum HY, Duncombe VM, Hewson JW, Thorpe ME (January 1976). "Vitamin B12 malabsorption associated with a normal Schilling test result". Med. J. Aust. 1 (3): 54–5. PMID 1263935.

- ↑ Inelmen EM, D'Alessio M, Gatto MR, Baggio MB, Jimenez G, Bizzotto MG, Enzi G (April 1994). "Descriptive analysis of the prevalence of anemia in a randomly selected sample of elderly people living at home: some results of an Italian multicentric study". Aging (Milano). 6 (2): 81–9. PMID 7918735.

- ↑ den Elzen WP, Westendorp RG, Frölich M, de Ruijter W, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J (November 2008). "Vitamin B12 and folate and the risk of anemia in old age: the Leiden 85-Plus Study". Arch. Intern. Med. 168 (20): 2238–44. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.20.2238. PMID 19001201.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Holt JT, DeWandler MJ, Arvan DA (May 1982). "Spurious elevation of the electronically determined mean corpuscular volume and hematocrit caused by hyperglycemia". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 77 (5): 561–7. PMID 7081150.

- ↑ Weiss GB, Bessman JD (1984). "Spurious automated red cell values in warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia". Am. J. Hematol. 17 (4): 433–5. PMID 6496462.

- ↑ Bessman JD, Banks D (December 1980). "Spurious macrocytosis, a common clue to erythrocyte cold agglutinins". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 74 (6): 797–800. PMID 7446489.