Bacteriophage

|

WikiDoc Resources for Bacteriophage |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Bacteriophage Most cited articles on Bacteriophage |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Bacteriophage |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Bacteriophage at Clinical Trials.gov Trial results on Bacteriophage Clinical Trials on Bacteriophage at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Bacteriophage NICE Guidance on Bacteriophage

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Bacteriophage Discussion groups on Bacteriophage Patient Handouts on Bacteriophage Directions to Hospitals Treating Bacteriophage Risk calculators and risk factors for Bacteriophage

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Bacteriophage |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

A bacteriophage (from 'bacteria' and Greek phagein, 'to eat') is any one of a number of viruses that infect bacteria. The term is commonly used in its shortened form, phage.

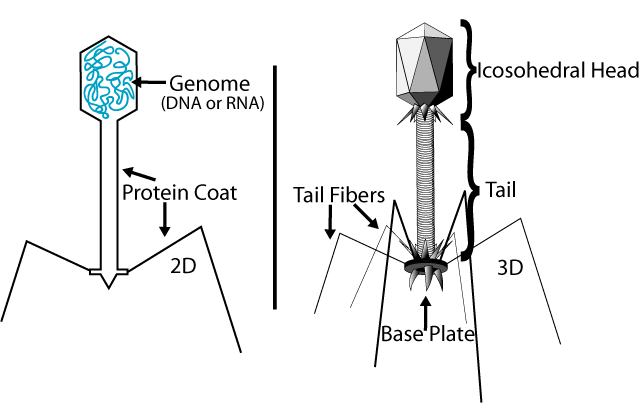

Typically, bacteriophages consist of an outer protein hull enclosing genetic material. The genetic material can be ssRNA (single stranded RNA), dsRNA, ssDNA, or dsDNA between 5 and 500 kilo base pairs long with either circular or linear arrangement. Bacteriophages are much smaller than the bacteria they destroy - usually between 20 and 200 nm in size.

Phages are estimated to be the most widely distributed and diverse entities in the biosphere.[1] Phages are ubiquitous and can be found in all reservoirs populated by bacterial hosts, such as soil or the intestines of animals. One of the densest natural sources for phages and other viruses is sea water, where up to 9×108 virions per milliliter have been found in microbial mats at the surface[2], and up to 70% of marine bacteria may be infected by phages.[3]

They have been used for over 60 years as an alternative to antibiotics in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.[4] They are seen as a possible therapy against multi drug resistant strains of many bacteria.

Classification of phages

The dsDNA tailed phages, or Caudovirales, account for 95% of all the phages reported in the scientific literature, and possibly make up the majority of phages on the planet.[1] However, there are other phages that occur abundantly in the biosphere, phages with different virions, genomes and lifestyles. Phages are classified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) according to morphology and nucleic acid.

| Order | Family | Morphology | Nucleic acid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caudovirales | Myoviridae | Non-enveloped, contractile tail | Linear dsDNA |

| Siphoviridae | Non-enveloped, long non-contractile tail | Linear dsDNA | |

| Podoviridae | Non-enveloped, short noncontractile tail | Linear dsDNA | |

| Tectiviridae | Non-enveloped, isometric | Linear dsDNA | |

| Corticoviridae | Non-enveloped, isometric | Circular dsDNA | |

| Lipothrixviridae | Enveloped, rod-shaped | Linear dsDNA | |

| Plasmaviridae | Enveloped, pleomorphic | Circular dsDNA | |

| Rudiviridae | Non-enveloped, rod-shaped | Linear dsDNA | |

| Fuselloviridae | Non-enveloped, lemon-shaped | Circular dsDNA | |

| Inoviridae | Non-enveloped, filamentous | Circular ssDNA | |

| Microviridae | Non-enveloped, isometric | Circular ssDNA | |

| Leviviridae | Non-enveloped, isometric | Linear ssRNA | |

| Cystoviridae | Enveloped, spherical | Segmented dsRNA |

History

Since ancient times, there have been documented reports of river water having the ability to cure infectious diseases, such as leprosy. In 1896, Ernest Hanbury Hankin reported that something in the waters of the Ganges and Jumna rivers in India had marked antibacterial action against cholera and could pass through a very fine porcelain filter. In 1915, British bacteriologist Frederick Twort, superintendent of the Brown Institution of London, discovered a small agent that infected and killed bacteria. He considered the agent either 1) a stage in the life cycle of the bacteria, 2) an enzyme produced by the bacteria themselves or 3) a virus that grew on and destroyed the bacteria. Twort's work was interrupted by the onset of World War I and shortage of funding. Independently, French-Canadian microbiologist Félix d'Hérelle, working at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, announced on September 3, 1917 that he had discovered "an invisible, antagonistic microbe of the dysentery bacillus". For d’Hérelle, there was no question as to the nature of his discovery: "In a flash I had understood: what caused my clear spots was in fact an invisible microbe ... a virus parasitic on bacteria." D'Hérelle called the virus a bacteriophage or bacteria-eater (from the Greek phagein meaning to eat). He also recorded a dramatic account of a man suffering from dysentery who was restored to good health by the bacteriophages. In 1926 in the Pulitzer-prizewinning novel Arrowsmith, Sinclair Lewis fictionalized the application of bacteriophages as a therapeutic agent. Also in the 1920s the Eliava Institute was opened in Tbilisi, Georgia to research this new science and put it into practice. In 2006 the UK Ministry of Defence took responsibility for a G8-funded Global Partnership Priority Eliava Project as a retrospective study to explore the potential of bacteriophages for the 21st century.

Replication

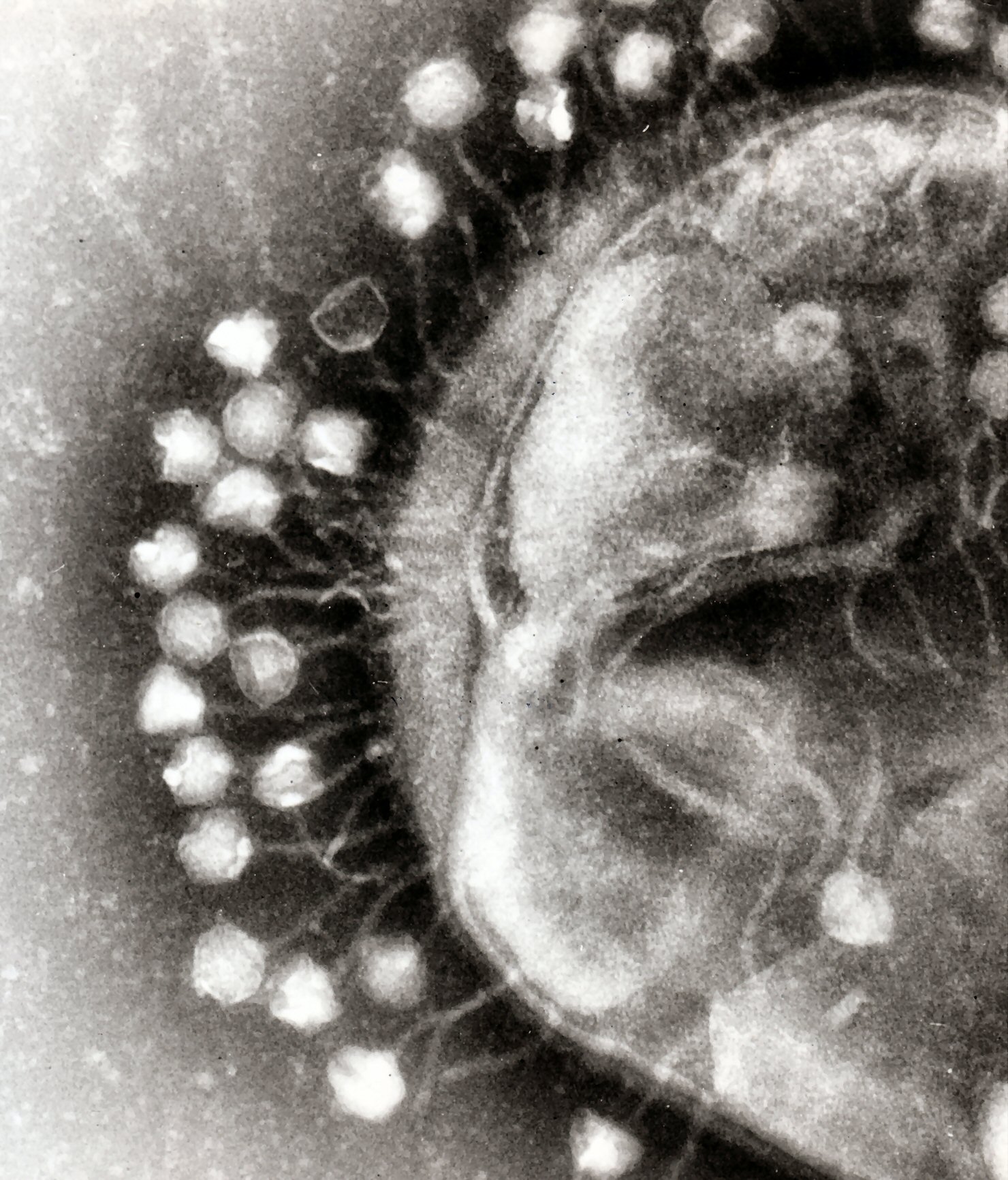

Bacteriophages may have a lytic cycle or a lysogenic cycle, but a few viruses are capable of carrying out both. With lytic phages such as the T4 phage, bacterial cells are broken open (lysed) and destroyed after immediate replication of the virion. As soon as the cell is destroyed, the new bacteriophages viruses can find new hosts. Lytic phages are the kind suitable for phage therapy.

In contrast, the lysogenic cycle does not result in immediate lysing of the host cell. Those phages able to undergo lysogeny are known as temperate phages. Their viral genome will integrate with host DNA and replicate along with it fairly harmlessly, or may even become established as a plasmid. The virus remains dormant until host conditions deteriorate, perhaps due to depletion of nutrients, then the endogenous phages (known as prophages) become active. At this point they initiate the reproductive cycle resulting in lysis of the host cell. As the lysogenic cycle allows the host cell to continue to survive and reproduce, the virus is reproduced in all of the cell’s offspring.

Sometimes prophages may provide benefits to the host bacterium while they are dormant by adding new functions to the bacterial genome in a phenomenon called lysogenic conversion. A famous example is the conversion of a harmless strain of Vibrio cholerae by a phage into a highly virulent one, which causes cholera. This is why temperate phages are not suitable for phage therapy.

Attachment and penetration

To enter a host cell, bacteriophages attach to specific receptors on the surface of bacteria, including lipopolysaccharides, teichoic acids, proteins or even flagella. This specificity means that a bacteriophage can only infect certain bacteria bearing receptors that they can bind to, which in turn determines the phage's host range. As phage virions do not move independently, they must rely on random encounters with the right receptors when in solution (blood, lymphatic circulation, irrigation, soil water etc.).

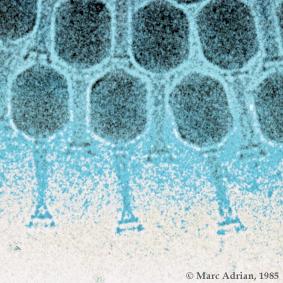

Complex bacteriophages use a syringe-like motion to inject their genetic material into the cell. After making contact with the appropriate receptor, the tail fibers bring the base plate closer to the surface of the cell. Once attached completely, the tail contracts, possibly with the help of ATP present in the tail (Prescott, 1993), injecting genetic material through the bacterial membrane.

Synthesis of proteins and nucleic acid

Within minutes, bacterial ribosomes start translating viral mRNA into protein. For RNA-based phages, RNA replicase is synthesized early in the process. Proteins modify the bacterial RNA polymerase so that it preferentially transcribes viral mRNA. The host’s normal synthesis of proteins and nucleic acids is disrupted, and it is forced to manufacture viral products instead. These products go on to become part of new virions within the cell, helper proteins which help assemble the new virions, or proteins involved in cell lysis. Walter Fiers (University of Ghent, Belgium) was the first to establish the complete nucleotide sequence of a gene (1972) and of the viral genome of Bacteriophage MS2 (1976).[5]

Virion assembly

In the case of the T4 phage, the construction of new virus particles involves the assistance of helper proteins. The base plates are assembled first, with the tails being built upon them afterwards. The head capsids, constructed separately, will spontaneously assemble with the tails. The DNA is packed efficiently within the heads. The whole process takes about 15 minutes.

Release of virions

Phages may be released via cell lysis or by host cell secretion. In the case of the T4 phage, in just over twenty minutes after injection upwards of three hundred phages will be released via lysis within a certain timescale. This is achieved by an enzyme called endolysin which attacks and breaks down the peptidoglycan. In contrast, "lysogenic" phages do not kill the host but rather become long-term parasites and make the host cell continually secrete more new virus particles. The new virions bud off the plasma membrane, taking a portion of it with them to become enveloped viruses possessing a viral envelope. All released virions are capable of infecting a new bacterium.

Phage therapy

Phages were discovered to be anti-bacterial agents and put to use as such soon after they were discovered, with varying success. However, antibiotics were discovered some years later and marketed widely, popular because of their broad spectrum; also easier to manufacture in bulk, store and prescribe. Hence development of phage therapy was largely abandoned in the West, but continued throughout 1940s in the former Soviet Union for treating bacterial infections, with widespread use including the soldiers in the Red Army - much of the literature being in Russian or Georgian, and unavailable for many years in the West. This has continued after the war, with widespread use continuing in Georgia and elsewhere in Eastern Europe. There is much anecdotal evidence and case studies; There have also been clinical trials in Poland,

Phase 2 human clinical trials are claimed to be nearing completion in a London hospital with ear infections[6] , and Phase 1 clinical trials are taking place in Lubbock, Texas in a wound care context.

Bacteriophage in the environment

Some time ago it was detected that phages are much more abundant in the water column of freshwater and marine habitats than previously thought and that they can cause significant mortality of bacterioplankton. Methods in phage community ecology have been developed to assess phage-induced mortality of bacterioplankton and its role for food web process and biogeochemical cycles, to genetically fingerprint phage communities or populations and estimate viral biodiversity by metagenomics. The release of lysis products by phages converts organic carbon from particulate (cells) to dissolved forms (lysis products), which makes organic carbon more bio-available and thus acts as a catalyst of geochemical nutrient cycles. Phages are not only the most abundant biological entities but probably also the most diverse ones. The majority of the sequence data obtained from phage communities has no equivalent in data bases. These data and other detailed analyses indicate that phage-specific genes and ecological traits are much more frequent than previously thought. In order to reveal the meaning of this genetic and ecological versatility, studies have to be performed with communities and at spatiotemporal scales relevant for microorganisms.[1]

Bacteriophages have also been used in hydrological tracing and modelling in river systems especially where surface water and groundwater interactions occur. The use if phage is preferred to the more conventional dye marker because they are significantly less adsorbed when passing through ground-waters and they are readily detected at very low concentrations. [7]

Bacteriophages and food fermentation

A broad number of food products, commodity chemicals, and biotechnology products are manufactured industrially by large-scale bacterial fermentation of various organic substrates. Because enormous amounts of bacteria are being cultivated each day in large fermentation vats, the risk that bacteriophage contamination rapidly brings fermentations to a halt and cause economical setbacks is a serious threat in these industries. The relationship between bacteriophages and their bacterial hosts is very important in the context of the food fermentation industry. Sources of phage contamination, measures to control their propagation and dissemination, and biotechnological defense strategies developed to restrain phages are of interest. The dairy fermentation industry has openly acknowledged the problem of phage and has been working with academia and starter culture companies to develop defense strategies and systems to curtail the propagation and evolution of phages for decades.[1]

Other areas of use

In August, 2006 the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved using bacteriophages on cheese to kill the Listeria monocytogenes bacteria, giving them GRAS status (Generally Recognized As Safe). [2] In July 2007, the same bacteriophages were approved for use on all food products. [3]Government agencies in the West have for several years been looking to Georgia and the Former Soviet Union for help with exploiting phages for counteracting bioweapons and toxins e.g. Anthrax, Botulism. There are many developments with this amongst research groups in the US. Other uses include spray application in horticulture for protecting plants and vegetable produce from decay and the spread of bacterial disease. Other applications for bacteriophages are as a biocide for environmental surfaces e.g. hospitals - and as a preventative treatment for catheters and medical devices prior to use in clinical settings. The technology now exists for phages to be applied to dry surfaces e.g. uniforms, curtains - even sutures for surgery. Clinical trials reported in the Lancet show success in veterinary treatment of pet dogs with otitis. Phage display is a different use of phages. It is a powerful yet simple technique involving a library of phages with a variable peptide linked to a surface protein. Each phage's genome encodes the variant of the protein displayed on its surface (hence the name), providing a link between the peptide variant and its encoding gene. Variant phages from the library can be selected through their binding affinity to an immobilized molecule (e.g. Botulism toxin to neutralize it). The bound selected phages can be multiplied by re-infecting a susceptible bacterial strain, thus allowing them to retrieve the peptides encoded in them for further study.

Model bacteriophages

Following is a list of bacteriophages that are extensively studied:

- λ phage - Lysogen

- T2 phage

- T4 phage (169 to 170 kbp, 200 nm long)

- T7 phage

- T12 phage

- R17 phage

- M13 phage

- MS2 phage (23-25 nm in size)

- G4 phage

- P1 phage

- P2 phage

- Phi X 174 phage

- N4 phage

- Φ6 phage

- Φ29 phage

- 186 phage

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Mc Grath S and van Sinderen D (editors). (2007). Bacteriophage: Genetics and Molecular Biology (1st ed. ed.). Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-14-1 .

- ↑ Wommack KE, Colwell RR (2000). "Virioplankton: viruses in aquatic ecosystems". Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64 (1): 69–114. PMID 10704475. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Prescott, L. (1993). Microbiology, Wm. C. Brown Publishers, ISBN 0-697-01372-3

- ↑ BBC Horizon (1997): The Virus that Cures - Documentary about the history of phage medicine in Russia and the West

- ↑ Fiers W et al., Complete nucleotide-sequence of bacteriophage MS2-RNA - primary and secondary structure of replicase gene, Nature, 260, 500-507, 1976

- ↑ Bacteriophages: Nature and Exploitation - Summary - powered by RegOnline

- ↑ C. Martin (1988) The Application of Bacteriophage Tracer Techniques in South West Water, Water and Environment Journal 2 (6) , 638–642 doi:10.1111/j.1747-6593.1988.tb01352.x

External links

- Häusler, T. (2006) "Viruses vs. Superbugs", Macmillan

- Phage.org general information on bacteriophages

- August 2007 news article from the BBC

- http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1079784

- BBC Horizon (1997): The Virus that Cures - Documentary about the history of phage medicine in Russia and the West

- NPR Science Friday podcast, "Using 'Phage' Viruses to Help Fight Infection", April 2008

- Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy

See also

- RNA viruses

- DNA viruses

- Phage ecology

- Phage monographs (a comprehensive listing of phage and phage-associated monographs, 1921-present)

- Phage scientific meetings

Template:Baltimore classification Template:Viral diseases

bg:Бактериофаг ca:Bacteriòfag cs:Bakteriofág da:Bakteriofag de:Bakteriophage el:Φάγος eo:Bakteriofago fa:باکتریوفاژ hr:Bakteriofag it:Batteriofago he:בקטריופאג' ka:ბაქტერიოფაგები lv:Bakteriofāgi lt:Bakteriofagas nl:Bacteriofaag no:Bakteriofag simple:Bacteriophage sk:Bakteriofág sl:Bakteriofag fi:Bakteriofagi sv:Bakteriofag uk:Бактеріофаги