Agonist

|

WikiDoc Resources for Agonist |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Agonist |

|

Media |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Agonist at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Agonist at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Agonist

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Directions to Hospitals Treating Agonist Risk calculators and risk factors for Agonist

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Agonist |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

In pharmacology an agonist is a substance that binds to a specific receptor and triggers a response in the cell. It mimics the action of an endogenous ligand (such as hormone or neurotransmitter) that binds to the same receptor.

Types

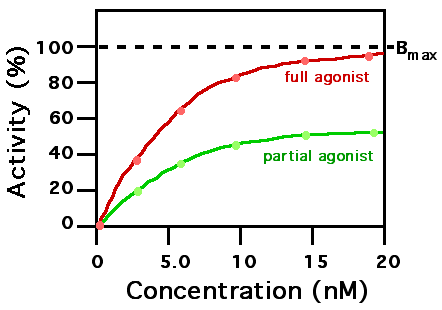

Full agonists bind (have affinity for) and activate a receptor, displaying full efficacy at that receptor.

One example of a drug that acts as a full agonist is isoproterenol which mimics the action of adrenaline at β adrenoreceptors.

Partial agonists (such as buspirone, aripiprazole, buprenorphine, or norclozapine) also bind and activate a given receptor, but have only partial efficacy at the receptor relative to a full agonist. They may also be considered ligands which display both agonistic and antagonistic effects - when both a full agonist and partial agonist are present, the partial agonist actually acts as a competitive antagonist, competing with the full agonist for receptor occupancy and producing a net decrease in the receptor activation observed with the full agonist alone.[1]

A co-agonist works with other co-agonists to produce the desired effect together. NMDA receptor activation requires the binding of both of its glutamate and glycine co-agonists. An antagonist blocks a receptor from activation by agonists. Clinically partial agonists can activate receptors to give a desired submaximal response when inadequate amounts of the endogenous ligand are present, or they can reduce the overstimulation of receptors when excess amounts of the endogenous ligand are present.[2]

A selective agonist is selective for one certain type of receptor. It can additionally be of any of the aforementioned types.

A physiological agonist is a substance that creates the same bodily responses, but does not bind to the same receptor.

Receptors can be activated or inactivated either by endogenous (such as hormones and neurotransmitters) or exogenous (such as drugs) agonists and antagonists, resulting in stimulating or inhibiting a biological response. To see how an agonist may activate a receptor see this link

New findings that broaden the conventional definition of pharmacology demonstrate that ligands can concurrently behave as agonist and antagonists at the same receptor, depending on effector pathways. Terms that describe this phenomenon are "functional selectivity" or "protean agonism".[3][4]

Activity (EC50)

Potency

The potency of an agonist is usually defined by its EC50 value. This can be calculated for a given agonist by determining the concentration of agonist needed to elicit half of the maximum biological response of the agonist. Elucidating an EC50 value is useful for comparing the potency of drugs with similar efficacies producing physiologically similar effects. The lower the EC50, the greater the potency of the agonist the lower the concentration of drug that is required to elicit the maximum biological response

Therapeutic index

When a drug is used therapeutically, it is important to understand the margin of safety that exists between the dose needed for the desired effect and the dose that produces unwanted and possibly dangerous side effects. This relationship, termed the therapeutic index, is defined as the ratio LD50:ED50. In general, the narrower this margin, the more likely it is that the drug will produce unwanted effects. The therapeutic index has many limitations, notably the fact that LD50 cannot be measured in humans and, when measured in animals, is a poor guide to the likelihood of unwanted effects in humans. Nevertheless, the therapeutic index emphasizes the importance of the margin of safety, as distinct from the potency, in determining the usefulness of a drug.

Etymology

From the Greek αγωνιστής (agōnistēs), contestant; champion; rival < αγων (agōn), contest, combat; exertion, struggle < αγω (agō), I lead, lead towards, conduct; drive

See also

- Receptor theory

- Inverse agonist

- Receptor antagonist

- Excitatory postsynaptic potential

- Allosteric modulator

- Intrinsic activity

- Dose response curve

References

- ↑ Principles and Practice of Pharmacology for Anaesthetists By Norton Elwy Williams, Thomas Norman Calvey Published 2001 Blackwell Publishing ISBN 0632056053

- ↑ Zhu BT (2005). "Mechanistic explanation for the unique pharmacologic properties of receptor partial agonists". Biomed. Pharmacother. 59 (3): 76–89. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2005.01.010. PMID 15795100.

- ↑ Kenakin T. (2001). Inverse, protean, and ligand-selective agonism: matters of receptor conformation. FASEB J. 15:598-611. PMID 11259378. Fulltext

- ↑ Urban J.D. et al. (2007). Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 320:1-13. PMID 16803859.

ar:ناهضة (علم الأدوية)

ca:Agonista

da:Agonist

de:Agonist (Pharmakologie)

he:אגוניסט

sl:Agonist

sr:Агониста

fi:Agonisti

sv:Agonist

th:อะโกนิสต์

it:Agonista