Acupuncture

Template:Alternative medical systems

|

WikiDoc Resources for Acupuncture |

|

Articles |

|---|

|

Most recent articles on Acupuncture Most cited articles on Acupuncture |

|

Media |

|

Powerpoint slides on Acupuncture |

|

Evidence Based Medicine |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Ongoing Trials on Acupuncture at Clinical Trials.gov Clinical Trials on Acupuncture at Google

|

|

Guidelines / Policies / Govt |

|

US National Guidelines Clearinghouse on Acupuncture

|

|

Books |

|

News |

|

Commentary |

|

Definitions |

|

Patient Resources / Community |

|

Patient resources on Acupuncture Discussion groups on Acupuncture Patient Handouts on Acupuncture Directions to Hospitals Treating Acupuncture Risk calculators and risk factors for Acupuncture

|

|

Healthcare Provider Resources |

|

Causes & Risk Factors for Acupuncture |

|

Continuing Medical Education (CME) |

|

International |

|

|

|

Business |

|

Experimental / Informatics |

Overview

Researchers using the protocols of evidence-based medicine have found good evidence that acupuncture is effective in treating nausea[1][2] and chronic low back pain[3][4], and moderate evidence for neck pain[5] and headache.[6] The WHO, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the American Medical Association (AMA) and various government reports have also studied and commented on the efficacy of acupuncture. There is general agreement that acupuncture is at least safe when administered by well-trained practitioners, and that further research is warranted. Though occasionally charged as pseudoscience, Dr. William F. Williams, author of Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience, notes that acupuncture --"once rejected as 'oriental fakery' -- is now (if grudgingly) recognized as engaged in something quite real."[7][8][9][10]

Traditional Chinese medicine's acupuncture theory, although based on empirical observation, predates use of the modern scientific method, and has received various criticisms based on modern scientific thinking. There is no generally-accepted anatomical or histological basis for the existence of acupuncture points or meridians.[11] Acupuncturists tend to perceive TCM concepts in functional rather than structural terms, i.e. as being useful in guiding evaluation and care of patients. [12] As the NIH consensus statement noted: "Despite considerable efforts to understand the anatomy and physiology of the "acupuncture points", the definition and characterization of these points remains controversial. Even more elusive is the basis of some of the key traditional Eastern medical concepts such as the circulation of Qi, the meridian system, and the five phases theory, which are difficult to reconcile with contemporary biomedical information but continue to play an important role in the evaluation of patients and the formulation of treatment in acupuncture."[8] Finally, neuroimaging research suggests that specific acupuncture points have distinct effects on cerebral activity in specific areas that are not otherwise predictable anatomically.[13]

Traditional theory

Chinese medicine is based on a different paradigm from scientific biomedicine. Its theory holds the following explanation of acupuncture:

Acupuncture treats the human body as a whole that involves several "systems of function" that are in some cases loosely associated with (but not identified on a one-to-one basis with) physical organs. Some systems of function, such as the "triple heater" (San Jiao, also called the "triple burner") have no corresponding physical organ, rather, represents the various jiaos or levels of the ventral body cavity (upper, middle and lower). Disease is understood as a loss of balance between the yin and yang energies, which bears some resemblance to homeostasis among the several systems of function, and treatment of disease is attempted by modifying the activity of one or more systems of function through the activity of needles, pressure, heat, etc. on sensitive parts of the body of small volume traditionally called "acupuncture points" in English, or "xue" (穴, cavities) in Chinese. This is referred to in TCM as treating "patterns of disharmony".

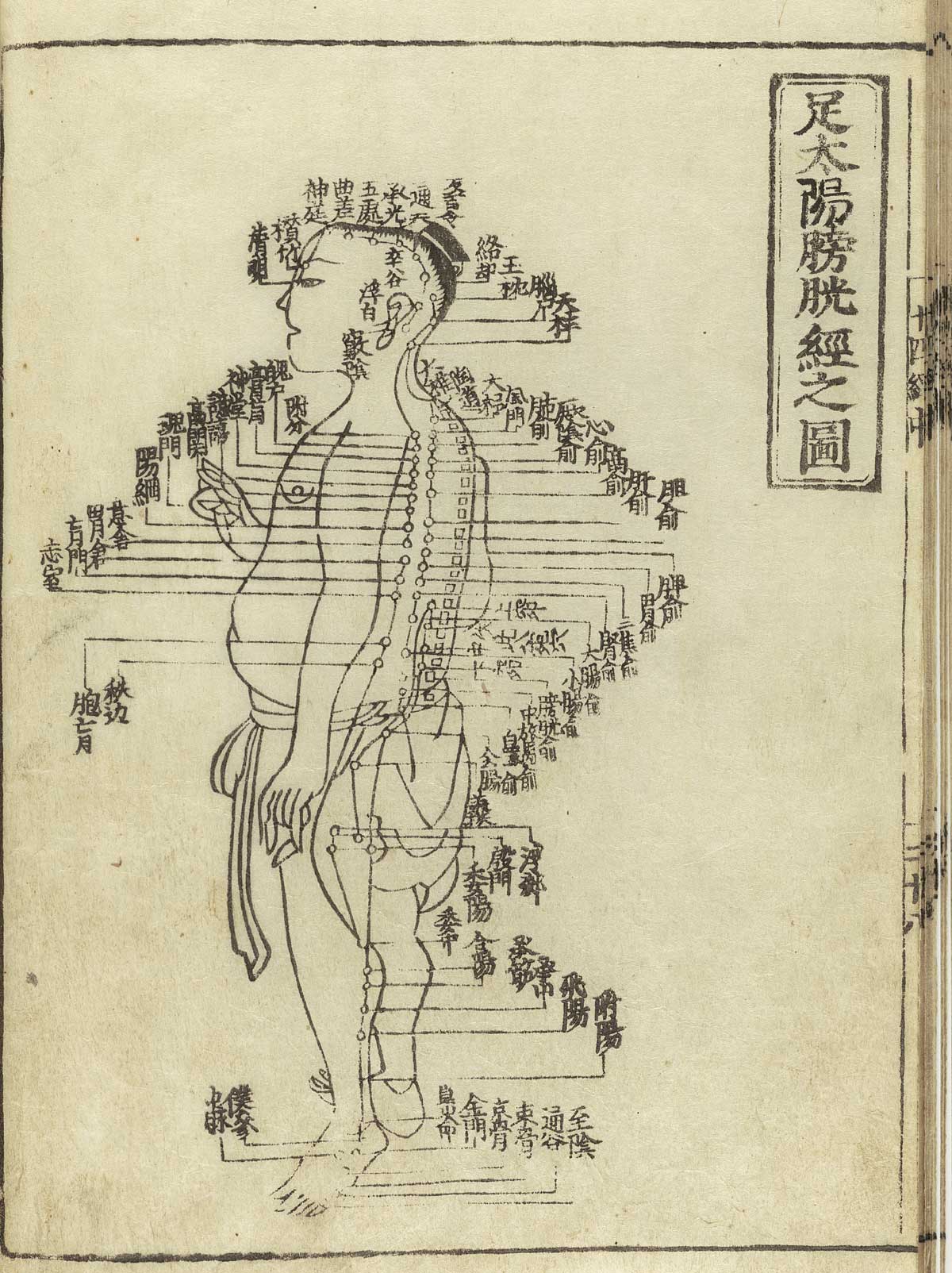

Treatment of acupuncture points may be performed along several layers of pathways, most commonly the twelve primary pathways meridians, located throughout the body. Other pathways include the Eight Extraordinary Pathways Qi Jing Ba Mai, the Luo Vessels, the Divergents and the Sinew Channels. Unaffiliated, or tender points, called "ah shi" (signifying "that's it", "ouch", or "oh yes") are generally used for treatment of local pain. Of the eight extraordinary pathways, only two have acupuncture points of their own. The other six meridians are "activated" by using a master and couple point technique which involves needling the acupuncture points located on the twelve main meridians that correspond to the particular extraordinary pathway. Ten of the primary pathways are named after organs of the body (Heart, Liver, etc.), one is named for the serous membrane that wraps the heart (Heart Protector or Pericardium), the last is the 'three spaces' (San Jiao). The pathways are capitalized to avoid confusion with a physical organ (for example, we write the "Heart meridian" as opposed to the "heart meridian"). The two independent extraordinary pathways Ren Mai and Du Mai are situated on the midline of the anterior and posterior aspects of the trunk and head respectively.

The twelve primary pathways run vertically, bilaterally, and symmetrically and every channel corresponds to and connects internally with one of the twelve Zang Fu ("organs"). This means that there are six yin and six yang channels. There are three yin and three yang channels on each arm, and three yin and three yang on each leg.

The three yin channels of the hand (Lung, Pericardium, and Heart) begin on the chest and travel along the inner surface (mostly the anterior portion) of the arm to the hand.

The three yang channels of the hand (Large intestine, San Jiao, and Small intestine) begin on the hand and travel along the outer surface (mostly the posterior portion) of the arm to the head.

The three [[Yin and yang|yin channels of the foot (Spleen, Liver, and Kidney) begin on the foot and travel along the inner surface (mostly posterior and medial portion) of the leg to the chest or flank.

The three yang channels of the foot (Stomach, Gallbladder, and Bladder) begin on the face, in the region of the eye, and travel down the body and along the outer surface (mostly the anterior and lateral portion) of the leg to the foot.

The movement of qi through each of the twelve channels is comprised of an internal and an external pathway. The external pathway is what is normally shown on an acupuncture chart and it is relatively superficial. All the acupuncture points of a channel lie on its external pathway. The internal pathways are the deep course of the channel where it enters the body cavities and related Zang-Fu organs. The superficial pathways of the twelve channels describe three complete circuits of the body, chest to hands, hands to head, head to feet, feet to chest, etc.

The distribution of qi through the pathways is said to be as follows (the based on the demarcations in TCM's Chinese Clock):

Lung channel of hand taiyin to Large Intestine channel of hand yangming to Stomach channel of foot yangming to Spleen channel of foot taiyin to Heart channel of hand shaoyin to Small Intestine channel of hand taiyang to Bladder channel of foot taiyang to Kidney channel of foot shaoyin to Pericardium channel of hand jueyin to San Jiao channel of hand shaoyang to Gallbladder channel of foot shaoyang to Liver channel of foot jueyin then back to the Lung channel of hand taiyin. Each channel occupies two hours, beginning with the Lung, 3AM-5AM, and coming full circle with the Liver 1AM-3AM.

Chinese medical theory holds that acupuncture works by normalizing the free flow of qi (a difficult-to-translate concept that pervades Chinese philosophy and is commonly translated as "vital energy"), blood and body fluids (jin ye) throughout the body. Pain or illnesses are treated by attempting to remedy local or systemic accumulations or deficiencies. Pain is considered to indicate blockage or stagnation of the flow of qi, blood and/or fluids, and an axiom of the medical literature of acupuncture is "no pain, no blockage; no blockage, no pain". The delicate balance between qi and blood is of primary concern in Chinese medical theory, hence the axiom blood is the mother of qi, and qi is the commander of blood. Both qi and blood work together to move (qi) and to nourish (blood) the body fluids.

Many patients claim to experience the sensations of stimulus known in Chinese as "deqi" ("obtaining the qi" or "arrival of the qi"). This kind of sensation was historically considered to be evidence of effectively locating the desired point. There are some electronic devices now available which will make a noise when what they have been programmed to describe as the "correct" acupuncture point is pressed.

The acupuncturist decides which points to treat by observing and questioning the patient in order to make a diagnosis according to the tradition which he or she utilizes. In TCM, there are four diagnostic methods: inspection, auscultation and olfaction, inquiring, and palpation (Cheng, 1987, ch. 12). Inspection focuses on the face and particularly on the tongue, including analysis of the tongue size, shape, tension, color and coating, and the absence or presence of teeth marks around the edge. Auscultation and olfaction refer, respectively, to listening for particular sounds (such as wheezing) and attending to body odor. Inquiring focuses on the "seven inquiries", which are: chills and fever; perspiration; appetite, thirst and taste; defecation and urination; pain; sleep; and menses and leukorrhea. Palpation includes feeling the body for tender "ashi" points, and palpation of the left and right radial pulses at two levels of pressure (superficial and deep) and three positions Cun, Guan, Chi(immediately proximal to the wrist crease, and one and two fingers' breadth proximally, usually palpated with the index, middle and ring fingers). Other forms of acupuncture employ additional diagnosic techniques. In many forms of classical Chinese acupuncture, as well as Japanese acupuncture, palpation of the muscles and the hara (abdomen) are central to diagnosis.

TCM perspective on treatment of disease

Although TCM is based on the treatment of "patterns of disharmony" rather than biomedical diagnoses, practitioners familiar with both systems have commented on relationships between the two. A given TCM pattern of disharmony may be reflected in a certain range of biomedical diagnoses: thus, the pattern called Deficiency of Spleen Qi could manifest as chronic fatigue, diarrhea or uterine prolapse. Likewise, a population of patients with a given biomedical diagnosis may have varying TCM patterns. These observations are encapsulated in the TCM aphorism "One disease, many patterns; one pattern, many diseases". (Kaptchuk, 1982)

Classically, in clinical practice, acupuncture treatment is typically highly-individualized and based on philosophical constructs, and subjective and intuitive impressions" and not on controlled scientific research[14].

Criticism of TCM theory

TCM theory predates use of the scientific method and has received various criticisms based on scientific reductionist thinking, since there is no physically verifiable anatomical or histological basis for the existence of acupuncture points or meridians.

Felix Mann, founder and past-president of the Medical Acupuncture Society (1959–1980), the first president of the British Medical Acupuncture Society (1980), and the author of the first comprehensive English language acupuncture textbook Acupuncture: The Ancient Chinese Art of Healing' first published in 1962, has stated in his book Reinventing Acupuncture: A New Concept of Ancient Medicine:

- "The traditional acupuncture points are no more real than the black spots a drunkard sees in front of his eyes." (p. 14)

and…

- "The meridians of acupuncture are no more real than the meridians of geography. If someone were to get a spade and tried to dig up the Greenwich meridian, he might end up in a lunatic asylum. Perhaps the same fate should await those doctors who believe in [acupuncture] meridians." (p. 31)[15]

Philosopher Robert Todd Carroll deems acupuncture a pseudoscience because it "confuse(s) metaphysical claims with empirical claims".[16] Carroll states that:

- "...no matter how it is done, scientific research can never demonstrate that unblocking chi by acupuncture or any other means is effective against any disease. Chi is defined as being undetectable by the methods of empirical science."[17]

A report for CSICOP on pseudoscience in China written by Wallace Sampson and Barry L. Beyerstein said:

- "A few Chinese scientists we met maintained that although Qi is merely a metaphor, it is still a useful physiological abstraction (e.g., that the related concepts of Yin and Yang parallel modern scientific notions of endocrinologic and metabolic feedback mechanisms). They see this as a useful way to unite Eastern and Western medicine. Their more hard-nosed colleagues quietly dismissed Qi as only a philosophy, bearing no tangible relationship to modern physiology and medicine."[18]

George A. Ulett, MD, PhD, Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, University of Missouri School of Medicine states: "Devoid of metaphysical thinking, acupuncture becomes a rather simple technique that can be useful as a nondrug method of pain control." He believes that the traditional Chinese variety is primarily a placebo treatment, but electrical stimulation of about 80 acupuncture points has been proven useful for pain control.[19]

Ted J. Kaptchuk, author of The Web That Has No Weaver, refers to acupuncture as "prescientific." Regarding TCM theory, Kaptchuk states:

- "These ideas are cultural and speculative constructs that provide orientation and direction for the practical patient situation. There are few secrets of Oriental wisdom buried here. When presented outside the context of Chinese civilization, or of practical diagnosis and therapeutics, these ideas are fragmented and without great significance. The "truth" of these ideas lies in the way the physician can use them to treat real people with real complaints." (1983, pp. 34-35)

According to the NIH consensus statement on acupuncture:

- "Despite considerable efforts to understand the anatomy and physiology of the "acupuncture points", the definition and characterization of these points remains controversial. Even more elusive is the basis of some of the key traditional Eastern medical concepts such as the circulation of Qi, the meridian system, and the five phases theory, which are difficult to reconcile with contemporary biomedical information but continue to play an important role in the evaluation of patients and the formulation of treatment in acupuncture."[8]

History

In China, the practice of acupuncture can perhaps be traced as far back as the stone age, with the Bian shi, or sharpened stones. Stone acupuncture needles dating back to 3000 B.C. have been found by archeologists in Inner Mongolia. [20][21] Clearer evidence exists from the 1st millennium BCE, and archeological evidence has been identified with the period of the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD). Forms of it are also described in the literature of traditional Korean medicine where it is called chimsul. It is also important in Kampo, the traditional medicine system of Japan.

Recent examinations of Ötzi, a 5,000-year-old mummy found in the Alps, have identified over 50 tattoos on his body, some of which are located on acupuncture points that would today be used to treat ailments Ötzi suffered from. Some scientists believe that this is evidence that practices similar to acupuncture were practised elsewhere in Eurasia during the early bronze age. According to an article published in The Lancet by Dorfer et al., "We hypothesised that there might have been a medical system similar to acupuncture (Chinese Zhenjiu: needling and burning) that was practised in Central Europe 5,200 years ago... A treatment modality similar to acupuncture thus appears to have been in use long before its previously known period of use in the medical tradition of ancient China. This raises the possibility of acupuncture having originated in the Eurasian continent at least 2000 years earlier than previously recognised."[1], [2].

Acupuncture's origins in China are uncertain. The earliest Chinese medical text that first describes acupuncture is the Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine (History of Acupuncture) Huangdi Neijing, which was compiled around 305–204 B.C. However, the Chinese medical texts (Ma-wang-tui graves, 68 BC) do not mention acupuncture. Some hieroglyphics have been found dating back to 1000 B.C. that may indicate an early use of acupuncture. Bian stones, sharp pointed rocks used to treat diseases in ancient times, have also been discovered in ruins; some scholars believe that the bloodletting for which these stones were likely used presages certain acupuncture techniques.[3]

R.C. Crozier in the book Traditional medicine in modern China (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1968) says the early Chinese Communist Party expressed considerable antipathy towards classical forms of Chinese medicine, ridiculing it as superstitious, irrational and backward, and claiming that it conflicted with the Party’s dedication to science as the way of progress. Acupuncture was included in this criticism. Reversing this position, Communist Party Chairman Mao later said that "Chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure house and efforts should be made to explore them and raise them to a higher level."[4]

Representatives were sent out across China to collect information about the theories and practices of Chinese medicine. Traditional Chinese Medicine is the formalized system of Chinese medicine that was created out of this effort. TCM combines the use of acupuncture, Chinese herbal medicine, tui na, and other modalities. After the Cultural Revolution, TCM instruction was incorporated into university medical curricula under the "Three Roads" policy, wherein TCM, biomedicine, and a synthesis of the two would all be encouraged and permitted to develop. After this time, forms of classical Chinese medicine other than TCM were outlawed, and some practitioners left China.

The first forms of acupuncture to reach the United States were brought by non-TCM practitioners -such as Chinese rail road workers- many employing styles that had been handed down in family lineages, or from master to apprentice (collectively known as "Classical Chinese Acupuncture").

In Vietnam, Dr. Van Nghi and colleagues used the classical Chinese medical texts and applied them in clinical conditions without reference to political screening. They rewrote the modern version: Trung E Hoc. Van Nghi was made the first President of the First World Congress of Chinese Medicine at Bejing in 1988 in recognition of his work.

In the 1970s, acupuncture became vogue in America after American visitors to China brought back firsthand reports of patients undergoing major surgery using acupuncture as their sole form of anesthesia. Since then, tens of thousands of treatments are now performed in this country each year for many types of conditions such as back pain, headaches, infertility, stress, and many other illnesses.

Clinical practice

Finding a Qualified Practitioner

Health care providers can be a resource for referral to acupuncturists, and some conventional medical practitioners—including physicians and dentists—practice acupuncture. In addition, national acupuncture organizations (which can be found through libraries or Web search engines) may provide referrals to acupuncturists.

- Check a practitioner's credentials. Most states require a license to practice acupuncture; however, education and training standards and requirements for obtaining a license to practice vary from state to state. Although a license does not ensure quality of care, it does indicate that the practitioner meets certain standards regarding the knowledge and use of acupuncture.

- Do not rely on a diagnosis of disease by an acupuncture practitioner who does not have substantial conventional medical training. If you have received a diagnosis from a doctor, you may wish to ask your doctor whether acupuncture might help.

Methods and Instruments

Most modern acupuncturists use disposable stainless steel needles of fine diameter (0.007" to 0.020", 0.18 mm to 0.51 mm), sterilized with ethylene oxide or by autoclave. These needles are far smaller in diameter (and therefore less painful) than the needles used to give shots, since they do not have to be hollow for purposes of injection. The upper third of these needles is wound with a thicker wire (typically bronze), or covered in plastic, to stiffen the needle and provide a handle for the acupuncturist to grasp while inserting. The size and type of needle used, and the depth of insertion, depend on the acupuncture style being practised.

Warming an acupuncture point, typically by moxibustion (the burning of a combination of herbs, primarily mugwort), is a different treatment than acupuncture itself and is often, but not exclusively, used as a supplemental treatment. The Chinese term zhēn jǐu (針灸), commonly used to refer to acupuncture, comes from zhen meaning "needle", and jiu meaning "moxibustion". Moxibustion is still used in the 21st century to varying degrees among the schools of oriental medicine. For example, one well known technique is to insert the needle at the desired acupuncture point, attach dried moxa to the external end of an acupuncture needle, and then ignite it. The moxa will then smolder for several minutes (depending on the amount adhered to the needle) and conduct heat through the needle to the tissue surrounding the needle in the patient's body. Another common technique is to hold a large glowing stick of moxa over the needles. Moxa is also sometimes burned at the skin surface, usually by applying an ointment to the skin to protect from burns, though burning of the skin is general practice in China.

An example of acupuncture treatment

In western medicine, vascular headaches (the kind that are accompanied by throbbing veins in the temples) are typically treated with analgesics such as aspirin and/or by the use of agents such as niacin that dilate the affected blood vessels in the scalp, but in acupuncture a common treatment for such headaches is to stimulate the sensitive points that are located roughly in the center of the webs between the thumbs and the palms of the patient, the hé gǔ points. These points are described by acupuncture theory as "targeting the face and head" and are considered to be the most important point when treating disorders affecting the face and head. The patient reclines, and the points on each hand are first sterilized with alcohol, and then thin, disposable needles are inserted to a depth of approximately 3-5 mm until a characteristic "twinge" is felt by the patient, often accompanied by a slight twitching of the area between the thumb and hand. Most patients report a pleasurable "tingling" sensation and feeling of relaxation while the needles are in place. The needles are retained for 15-20 minutes while the patient rests, and then are removed.

In the clinical practice of acupuncturists, patients frequently report one or more of certain kinds of sensation that are associated with this treatment, sensations that are stronger than those that would be felt by a patient not suffering from a vascular headache:

- Extreme sensitivity to pain at the points in the webs of the thumbs.

- In bad headaches, a feeling of nausea that persists for roughly the same period as the stimulation being administered to the webs of the thumbs.

- Simultaneous relief of the headache. (See Zhen Jiu Xue, p. 177f et passim.)

Indications according to acupuncturists in the West

According to the American Academy of Medical Acupuncture (2004), acupuncture may be considered as a complementary therapy for the conditions in the list below[22]. The conditions labeled with * are also included in the World Health Organization list of acupuncture indications.[23]. These cases, however, are based on clinical experience, and not necessarily on controlled clinical research: furthermore, the inclusion of specific diseases are not meant to indicate the extent of acupuncture's efficacy in treating them.[23]

- Abdominal distention/flatulence*

- Acute and chronic pain control*

- Allergic sinusitis *

- Anesthesia for high-risk patients or patients with previous adverse responses to anesthetics

- Anorexia

- Anxiety, fright, panic*

- Arthritis/arthrosis *

- Atypical chest pain (negative workup)

- Bursitis, tendinitis, carpal tunnel syndrome*

- Certain functional gastrointestinal disorders (nausea and vomiting, esophageal spasm, hyperacidity, irritable bowel) *

- Cervical and lumbar spine syndromes*

- Constipation, diarrhea *

- Cough with contraindications for narcotics

- Drug detoxification *

- Dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain *

- Frozen shoulder *

- Headache (migraine and tension-type), vertigo (Meniere disease), tinnitus *

- Idiopathic palpitations, sinus tachycardia

- In fractures, assisting in pain control, edema, and enhancing healing process

- Muscle spasms, tremors, tics, contractures*

- Neuralgias (trigeminal, herpes zoster, postherpetic pain, other)

- Paresthesias *

- Persistent hiccups*

- Phantom pain

- Plantar fasciitis*

- Post-traumatic and post-operative ileus *

- Premenstrual syndrome [24]

- Selected dermatoses (urticaria, pruritus, eczema, psoriasis)

- Sequelae of stroke syndrome (aphasia, hemiplegia) *

- Seventh nerve palsy

- Severe hyperthermia

- Sprains and contusions

- Temporo-mandibular joint derangement, bruxism *

- Urinary incontinence, retention (neurogenic, spastic, adverse drug effect) *

Additionally, other sources advocate the use of acupuncture for the following conditions:

- Infertility, regarding in vitro fertilization, see Expansions of in vitro fertilization - acupuncture

Scientific theories and mechanisms of action

Many hypotheses have been proposed to address the physiological mechanisms of action of acupuncture. To date, more than 10,000 scientific research studies have been published on acupuncture as cataloged by the National Library of Medicine database.

Neurohormonal theory

Pain transmission can also be modulated at many other levels in the brain along the pain pathways, including the periaqueductal gray, thalamus, and the feedback pathways from the cerebral cortex back to the thalamus. Each of these brain structure processes different aspect of the pain — from experiencing emotional pain to the perception of what the pain feels like to the recognition of how harmful the pain is to localizing where the pain is coming from. Pain blockade at these brain locations are often mediated by neurohormones, especially those that bind to the opioid receptors (pain-blockade site). Pain relief by morphine drug (exogenous opioid) is acting on the same opioid receptor (where pain blockade occurs) as endorphins (endogenous opioids) that the brain produces and releases.

Some studies suggest that the Analgesic (pain-killing) action of acupuncture is mediated by stimulating the release of natural endorphins in the brain. This can be proven scientifically by blocking the action of endorphins (or morphine) using a drug called naloxone. When naloxone is administered to the patient, the analgesic effects of morphine can be reversed, causing the patient to feel pain again. When naloxone is administered to an acupunctured patient, the analgesic effect of acupuncture can also be reversed, causing the patient to report an increased level of pain. This demonstrates that the site of action of acupuncture may be mediated through the natural release of endorphins by the brain, which can be reversed by naloxone.[25][26][27][28] Such analgesic effect can also be shown to last more than an hour after acupuncture stimulation by recording the neural activity directly in the thalamus (pain processing site) of the monkey's brain.[29] Furthermore, there is a large overlap between the nervous system and acupuncture trigger points (points of maximum tenderness in myofascial pain syndrome.[30]

The sites of action of acupuncture-induced analgesia are also confirmed to be mediated through the thalamus (where emotional pain/suffering is processed) using modern-day powerful non-invasive fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging)[31] and PET (positron emission tomography)[32] brain imaging techniques,[33] and via the feedback pathway from the cerebral cortex (where cognitive feedback signal to the thalamus distinguishing whether the pain is noxious (painful) or innocuous (non-harmful)) using electrophysiological recording of the nerve impulses of neurons directly in the cortex, which shows inhibitory action when acupuncture stimulus was applied.[34]

Recently acupuncture has been shown to increase the nitric oxide levels in treated regions and resulting in increased local blood circulation,[35] an outcome found in other studies.[36] Effects on local inflammation and ischemia have also been previously reported.[37]

Histological studies

Bonghan Kim proposed that meridians and acupuncture points exist in the form of distinctive anatomical structures in his Bonghan Theory.[38] [39] [40]

Scientific Method and the Assessment of Chinese Medical Theory and Techniques

Views of proponents

Criticism of TCM theory hinges on the question of how to assess 'intangible' concerns. There is an assumption that all knowledge can be tested by randomly-controlled double-blind studies, and that anything not susceptible to this method of assessment must be jettisoned as unverifiable. Yet the difficulty is not in the methodology, but rather that the nature of Traditional Chinese Medicine itself makes it difficult to subject it as a whole, or subsets of the medical theory, to this type of assessment.

The theory, practice and techniques of Chinese medicine evolved over many thousands of years, well in advance of a formal articulation of the scientific method. Nevertheless, the principles of the scientific method have been used throughout the development of Chinese medical knowledge. Documentation of developments allowed practitioners to evaluate each other's theoretical and practical hypotheses, and what was shown to be effective and/or consistent with observable phenomena was kept, and the remainder discarded over time.

Chinese medicine is inherently individually applied. Given that the health of the entire individual is taken into account for each patient, any two patients, even with the same diagnosis, will receive different treatments based on their constitutional differences, their pattern of response to treatment, and so on. In addition, each treatment may vary from the previous one, in the same way that a masseur might use strokes in a different order, or different strokes, to treat exactly the same condition, from one treatment to the next.

Thus the very complexity and flexibility of this medical system makes it extremely difficult to run clinical trials – a cohort of many thousands would have to be evaluated in order to even begin to assess any claims made for or against the medicine. Clinical trials are still a valuable exercise, but they are not sufficient to determine conclusively whether either the individual constituents of the medical theory (e.g. acupuncture points), or the medical theory as a whole, are valid.

Views of critics

One of the major criticisms of studies which purport to find that acupuncture is anything more than a placebo is that most such studies are not (in the view of critics) properly conducted. Many are not double blinded and are not randomized. However, double-blinding is not a trivial issue in acupuncture: since acupuncture is a procedure and not a pill, it is difficult to design studies in which the person providing treatment is blinded as to the treatment being given. The same problem arises in double-blinding procedures used in biomedicine, including virtually all surgical procedures, dentistry, physical therapy, etc.; the 1997 National Institute for Health Consensus Statement notes such issues with regard to sham acupuncture (needling performed superficially a/o at non-acupuncture sites), a technique often used in studies purporting to be double-blinded.[8] See also Criticism of evidence-based medicine. Tonelli, a prominent critic of EBM, argues that complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) cannot be EBM-based unless the definition of evidence is changed. Tonelli also says "the methods of developing knowledge within CAM currently have limitations and are subject to bias and varied interpretation. CAM must develop and defend a rational and coherent method for assessing causality and efficacy, though not necessarily one based on the results of controlled clinical trials."[41]

Some researchers argue that there is no evidence that acupuncture has any affect on the pathogenesis of viruses and microorganisms, or on human physiology, with the exception of the neurological pathways associated with the nerve cells that were stimulated by them. Thus, the most promising clinical application of acupuncture is in the area of pain control.

Some researchers argue that to date there is no conclusive scientific evidence indicating that the procedure has any effectiveness beyond that of a placebo. They argue that studies on acupuncture that meet scientific standards of experimentation have concluded two things: acupuncture is usually more effective than no treatment or a placebo in pill form, and that there is no significant difference in the effectiveness of acupuncture and “sham” acupuncture, which is often used as a control.[42] These researchers therefore conclude that acupuncture's effect is either caused by the tendency of extended, invasive procedures to generate more powerful placebo effects than pills or by the general stimulation of afferent nerve endings at the surface of the skin, causing the release of pain relieving biochemical compounds such as endorphins (this can also be done with jalapeno peppers, electricity, and various other form of stimulation). It may also be a combination of these two effects.

The vast majority of research on acupuncture is conducted by researchers in China, and Ernst et al. argue that there exist major flaws in the design of the experiments, as well as selective reporting of results, and conclude that no conclusions can be drawn from them.[43] Some researchers argue that numerous experimental difficulties have prevented the conclusive establishment of a causative relationship (if it exists) between pain relief and the administration of acupuncture. These include the subjective nature of pain measurement and the pervasive influence of psychological factors such as suggestion, confirmation bias, and the distraction of being poked by a needle. Also, they argue, the tendency of chronic pain to ebb and flow on its own without any external intervention leads people to falsely perceive that the last measure they took before the pain subsided was the cause of the relief. This is a logical fallacy known as post hoc ergo propter hoc.

Scientific research into efficacy

Evidence-based medicine

There is scientific agreement that an evidence-based medicine (EBM) framework should be used to assess health outcomes and that systematic reviews with strict protocols are essential. Organisations such as the Cochrane Collaboration and Bandolier publish such reviews.

For low back pain, a Cochrane review (2005) stated:

- Thirty-five RCTs covering 2861 patients were included in this systematic review. There is insufficient evidence to make any recommendations about acupuncture or dry-needling for acute low-back pain. For chronic low-back pain, results show that acupuncture is more effective for pain relief than no treatment or sham treatment, in measurements taken up to three months. The results also show that for chronic low-back pain, acupuncture is more effective for improving function than no treatment, in the short-term. Acupuncture is not more effective than other conventional and "alternative" treatments. When acupuncture is added to other conventional therapies, it relieves pain and improves function better than the conventional therapies alone. However, effects are only small. Dry-needling appears to be a useful adjunct to other therapies for chronic low-back pain.[44] A review by Manheimer et al. in Annals of Internal Medicine (2005) reached conclusions similar to Cochrane's review on low back pain.[45]

For nausea and vomiting: The Cochrane review (2006) on the use of the P6 acupoint for the reduction of post-operative nausea and vomiting concluded that "compared with anti emetic prophylaxis, P6 acupoint stimulation seems to reduce the risk of nausea but not vomiting".[46] Cochrane also stated: "Electroacupuncture is effective for first day vomiting after chemotherapy, but trials considering modern antivomiting drugs are needed."[47] Bandolier said "P6 acupressure in two studies showed 52% of patients with control having a success, compared with 75% with P6 acupressure"[2] and that one in five adults, but not children showed reduction in early postoperative nausea.[48] A review published by the Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine, however, argued that at the time of writing (2005) the data "are insufficiently reliable to confirm such an effect".[49]

A 2007 Cochrane Review for the use of acupuncture for neck pain stated:

- There is moderate evidence that acupuncture relieves pain better than some sham treatments, measured at the end of the treatment. There is moderate evidence that those who received acupuncture reported less pain at short term follow-up than those on a waiting list. There is also moderate evidence that acupuncture is more effective than inactive treatments for relieving pain post-treatment and this is maintained at short-term follow-up.[5]

For headache, Cochrane concluded (2006) that "(o)verall, the existing evidence supports the value of acupuncture for the treatment of idiopathic headaches. However, the quality and amount of evidence are not fully convincing. There is an urgent need for well-planned, large-scale studies to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of acupuncture under real-life conditions." [5]. Bandolier (1999) states: "There is no evidence from high quality trials that acupuncture is effective for the treatment of migraine and other forms of headache. The trials showing a significant benefit of acupuncture were of dubious methodological quality. Overall, the trials were of poor methodological quality."[6]

For osteoarthritis, Bandolier, commenting on a 1997 review by Edzard Ernst, stated: [7] "There is no evidence that acupuncture is more effective than sham/placebo acupuncture for the relief of joint pain due to osteoarthritis (OA)."

For fibromyalgia, a systematic review of the best 5 randomized controlled trials available found mixed results.[50] Three positive studies, all using electro-acupunture, found short term benefits.

For the following conditions, the Cochrane Collaboration concluded there is insufficient evidence that acupuncture is beneficial, often because of the paucity and poor quality of the research and that further research would be needed to support claims for efficacy:

- Giving up smoking

- Chronic asthma

- Bell's palsy

- Shoulder pain

- Lateral elbow pain

- Acute stroke

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Depression

- Induction of labour

In practice, EBM does not demand that doctors ignore research outside its "top-tier" criteria [51].

Evidence from neuroimaging studies

Acupuncture appears to have distinct effects on cortical activity, as demonstrated by MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and PET (positron emission tomography). Researchers from the University of Southampton, UK and Purpan Hospital of Toulouse, France, summarize the literature:

- Investigating Acupuncture Using Brain Imaging Techniques: The Current State of Play: George T. Lewith, Peter J. White and Jeremie Pariente. "We have systematically researched and reviewed the literature looking at the effect of acupuncture on brain activation as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography. These studies show that specific and largely predictable areas of brain activation and deactivation occur when considering the traditional Chinese functions attributable to certain specific acupuncture points. For example, points associated with hearing and vision stimulates the visual and auditory cerebral areas respectively."[13]

NIH consensus statement

According to the National Institutes of Health:[9]

- Preclinical studies have documented acupuncture's effects, but they have not been able to fully explain how acupuncture works within the framework of the Western system of medicine that is commonly practiced in the United States.

In 1997, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a consensus statement on acupuncture that concluded that

- there is sufficient evidence of acupuncture's value to expand its use into conventional medicine and to encourage further studies of its physiology and clinical value[8].

The statement was not a policy statement of the NIH [9] but rather the assessment of a panel convened by the NIH.

The NIH consensus statement said that

- the data in support of acupuncture are as strong as those for many accepted Western medical therapies

and added that

- there is clear evidence that needle acupuncture is efficacious for adult postoperative and chemotherapy nausea and vomiting and probably for the nausea of pregnancy... There is reasonable evidence of efficacy for postoperative dental pain... reasonable studies (although sometimes only single studies) showing relief of pain with acupuncture on diverse pain conditions such as menstrual cramps, tennis elbow, and fibromyalgia...

The NIH consensus statement summarized and made a prediction:

- Acupuncture as a therapeutic intervention is widely practiced in the United States. While there have been many studies of its potential usefulness, many of these studies provide equivocal results because of design, sample size, and other factors. The issue is further complicated by inherent difficulties in the use of appropriate controls, such as placebos and sham acupuncture groups. However, promising results have emerged, for example, showing efficacy of acupuncture in adult postoperative and chemotherapy nausea and vomiting and in postoperative dental pain. There are other situations such as addiction, stroke rehabilitation, headache, menstrual cramps, tennis elbow, fibromyalgia, myofascial pain, osteoarthritis, low back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and asthma, in which acupuncture may be useful as an adjunct treatment or an acceptable alternative or be included in a comprehensive management program. Further research is likely to uncover additional areas where acupuncture interventions will be useful.

The NIH's National Center For Complementary And Alternative Medicine continues to abide by the recommendations of the NIH Consensus Statement [10].

American Medical Association statement

In 1997, the following statement was adopted as policy of the American Medical Association (AMA), an association of medical doctors and medical students, after a report on a number of alternative therapies including acupuncture:[52]

"There is little evidence to confirm the safety or efficacy of most alternative therapies. Much of the information currently known about these therapies makes it clear that many have not been shown to be efficacious. Well-designed, stringently controlled research should be done to evaluate the efficacy of alternative therapies."

German study

A German study published in the September 2007 issue of the Archives of Internal Medicine found that nearly half of patients treated with acupuncture or a sham treatment felt relief from chronic low back pain over a period of months compared to just nearly a quarter of those receiving a variety of more conventional treatments (drugs, heat, massage, etc.)[53][54] The greater benefit of the real and sham treatments were not significantly different.

Safety and risks

Because acupuncture needles penetrate the skin, many forms of acupuncture are invasive procedures, and therefore not without risk. Injuries are rare among patients treated by trained practitioners.[55][56]

Certain forms of acupuncture such as the Japanese Tōyōhari and Shōnishin often use non-invasive techniques, in which specially-designed needles are rubbed or pressed against the skin. These methods are common in Japanese pediatric use.

Acupuncture Side Effects and Risks

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates acupuncture needles for use by licensed practitioners, requiring that needles be manufactured and labeled according to certain standards. For example, the FDA requires that needles be sterile, nontoxic, and labeled for single use by qualified practitioners only.

Relatively few complications from the use of acupuncture have been reported to the FDA, in light of the millions of people treated each year and the number of acupuncture needles used. Still, complications have resulted from inadequate sterilization of needles and from improper delivery of treatments. Practitioners should use a new set of disposable needles taken from a sealed package for each patient and should swab treatment sites with alcohol or another disinfectant before inserting needles. When not delivered properly, acupuncture can cause serious adverse effects, including infections and punctured organs.

Common, minor adverse events

A survey by Ernst et al. of over 400 patients receiving over 3500 acupuncture treatments found that the most common adverse effects from acupuncture were:[10]

- Minor bleeding after removal of the needles, seen in roughly 3% of patients. (Holding a cotton ball for about one minute over the site of puncture is usually sufficient to stop the bleeding.)

- Hematoma, seen in about 2% of patients, which manifests as bruises. These usually go away after a few days.

- Dizziness, seen in about 1% of patients. Some patients have a conscious or unconscious fear of needles which can produce dizziness and other symptoms of anxiety. Patients are usually treated lying down in order to reduce likelihood of fainting.

The survey concluded: "Acupuncture has adverse effects, like any therapeutic approach. If it is used according to established safety rules and carefully at appropriate anatomic regions, it is a safe treatment method."[10]

Other injury

Other risks of injury from the insertion of acupuncture needles include:

- Nerve injury, resulting from the accidental puncture of any nerve.

- Brain damage or stroke, which is possible with very deep needling at the base of the skull.

- Pneumothorax from deep needling into the lung.[57]

- Kidney damage from deep needling in the low back.

- Haemopericardium, or puncture of the protective membrane surrounding the heart, which may occur with needling over a sternal foramen (an undetectable hole in the breastbone which can occur in up to 10% of people).

- Risk of terminating pregnancy with the use of certain acupuncture points that have been shown to stimulate the production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and oxytocin.

These risks are slight and can all be avoided through proper training of acupuncturists. For correct perspective, their risk should be compared to the level of side effects of common drugs and biomedical treatment - see below. Graduates of medical schools and (in the US) accreditated acupuncture schools receive thorough instruction in proper technique so as to avoid these events. (Cf. Cheng, 1987)

Risks from omitting orthodox medical care

Some doctors believe that receiving any form of alternative medical care without also receiving orthodox western medical care is inherently risky, since undiagnosed disease may go untreated and could worsen. For this reason many acupuncturists and doctors prefer to consider acupuncture a complementary therapy rather than an alternative therapy.

Critics also express concern that unethical or naive practitioners may induce patients to exhaust financial resources by pursuing ineffective treatment.[11][12] However, many recent public health departments in modern countries have acknowledged the benefits of acupuncture by instituting regulations, ultimately raising the level of medicine practiced in these jurisdictions.[13][14][15]

Safety compared to other treatments

Commenting on the relative safety of acupuncture compared to other treatments, the NIH consensus panel stated that "(a)dverse side effects of acupuncture are extremely low and often lower than conventional treatments." They also stated:

- "the incidence of adverse effects is substantially lower than that of many drugs or other accepted medical procedures used for the same condition. For example, musculoskeletal conditions, such as fibromyalgia, myofascial pain, and tennis elbow... are conditions for which acupuncture may be beneficial. These painful conditions are often treated with, among other things, anti-inflammatory medications (aspirin, ibuprofen, etc.) or with steroid injections. Both medical interventions have a potential for deleterious side effects but are still widely used and are considered acceptable treatments."

In a Japanese survey of 55,291 acupuncture treatments given over five years by 73 acupuncturists, 99.8% of them were performed with no significant minor adverse effects and zero major adverse incidents (Hitoshi Yamashita, Bac, Hiroshi Tsukayama, BA, Yasuo Tanno, MD, PhD. Kazushi Nishijo, PhD, JAMA). Two combined studies in the UK of 66,229 acupuncture treatments yielded only 134 minor adverse events. (British Medical Journal 2001 Sep 1). The total of 121,520 treatments with acupuncture therapy were given with no major adverse incidents (for comparison, a single such event would have indicated a 0.0008% incidence).

This is in comparison to 2,216,000 serious adverse drug reactions that occurred in hospitals 1994. (Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN., JAMA. 1998 Apr 15;279(15):1200-5.) So to compare indirectly, Acupuncture has a 0.2% chance of causing a minor adverse effect compared to prescription medications having a 6.7% chance of causing a serious adverse event in a hospital setting.

Legal and political status

Acupuncturists may also practice herbal medicine or tui na, or may be medical acupuncturists, who are trained in allopathic medicine but also practice acupuncture in a simplified form. License is regulated by the state or province in many countries, and often requires passage of a board exam.

United States

In the United States, acupuncturists are generally referred to by the professional title "Licensed Acupuncturist", abbreviated "L.Ac.". They are also known as Acupuncture Physicians in the state of Florida, and are treated as primary care physicians there. Other states, like Illinois, which are considered conservative, not progressive, in their acupuncture licensing, now allow acupuncturists to practice without a referral from another medical practitioner. Thus, effectively, acupuncturists are recognized as independent physicians in these states as well. The abbreviation "Dipl. Ac." stands for "Diplomate of Acupuncture" and signifies that the holder is board-certified by the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine. Professional degrees are usually at the level of a Master's degree and include "M.Ac." (Master's in Acupuncture), "M.S.Ac." (Master's of Science in Acupuncture), "M.S.O.M" (Master's of Science in Oriental Medicine), and "M.A.O.M." (Master's of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine). "O.M.D." signifies Doctor of Oriental Medicine, and "C.M.D." signifies Doctor in Chinese Medicine (zhong Yi,中医); these titles may be used by graduates of Chinese medical schools, or by American graduates of certain postgraduate programs. The O.M.D. and C.M.D. are not recognized by the Accreditation Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (ACAOM), which accredits American educational programs in acupuncture. However, the O.M.D. (Doctor of Oriental Medicine) and D.O.M. (Doctor of Oriental Medine) degrees have been approved by some states. Each state regulates the practice of acupuncture within its territory. The ACAOM is currently beginning the process of accrediting the "Doctor of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine" (DAOM) degree, and this new degree will represent the terminal degree in the field. The Oregon College of Oriental Medicine[16] and Bastyr University were the first two institutions in the United States to offer the DAOM, and it is estimated that within the next ten years the DAOM degree will replace all master's level training programs in the United States.

In the USA, acupuncture is practiced by a variety of healthcare providers. Practitioners who specialize in Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine are usually referred to as "licensed acupuncturists", or L.Ac.'s. Other healthcare providers such as physicians, dentists and chiropractors sometimes also practice acupuncture, though they may often receive less training than L.Ac.'s. L.Ac.'s generally receive from 2500 to 4000 hours of training in Chinese medical theory, acupuncture, and basic biosciences. Some also receive training in Chinese herbology and/or bodywork. The amount of training required for healthcare providers who are not L.Ac.'s varies from none to a few hundred hours, and in Hawaii the practice of acupuncture requires full training as a licensed acupuncturist. The National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine tests practitioners to ensure they are knowledgeable about Chinese medicine and appropriate sterile technique. Many states require this test for licensing, but each state has its own laws and requirements. In some states, acupuncturists are required to work with an M.D. in a subservient relationship, even if the M.D. has no training in acupuncture.

Acupuncture is becoming accepted by the general public and by doctors. Over fifteen million Americans tried acupuncture in 1994. A poll of American doctors in 2005 showed that 60% believe acupuncture was at least somewhat effective, with the percentage increasing to 75% if acupuncture is considered as a complement to conventional treatment.

In 1996, the Food and Drug Administration changed the status of acupuncture needles from Class III to Class II medical devices, meaning that needles are regarded as safe and effective when used appropriately by licensed practitioners [17] [18].

Canada

In the province of British Columbia the TCM practitioners and Acupuncturists Bylaws were approved by the provincial government on April 12, 2001. The governing body, College of Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners and Acupuncturists of British Columbia provides professional licensing. Acupuncturists began lobbying the B.C. government in the 1970s for regulation of the profession which was achieved in 2003.

In Ontario, the practice of acupuncture is now regulated by the Traditional Chinese Medicine Act, 2006, S.o. 2006, chapter 27. The government is in the process of establishing a College whose mandate will be to oversee the implementation of policies and regulations relating to the profession. Practitioners of Traditional Chinese medicine will be permitted to use the title 'Doctor of Traditional Chinese medicine'. In addition, they will be permitted to communicate a diagnosis to patients based on Traditional Chinese medicine techniques for diagnosis. Other regulated Health Care Professionals, such as naturopaths, physicians, physiotherapists, chiropractors, dentists, or massage therapists can perform acupuncture treatments when they fulfill educational requirements set up by their regulatory colleges. It is noteworthy, however, that the school (philosophy and approach) and style of acupuncture differs depending on the training of the practitioner.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, British Acupuncture Council (BAcC) members observe the Code of Safe Practice with standards of hygiene and sterilisation of equipment. Members use single-use pre-sterilised disposable needles. Similar standards apply in most jurisdictions in the United States and Australia.

Acupuncture is also practiced by a number of registered medical practitioners, many of whom belong to the British Medical Acupunture Society (BMAS), which also publishes a quarterly journal "Acupuncture in Medicine". Medical practitioners of acupuncture in the UK vary in the degree to which they take account of traditional concepts like meridians, some thinking them to be very useful whilst others tend to concentrate on palpable "trigger points". Other acupuncture groups are the British Academy of Western Medical Acupuncture (BAWMA) - nurses trained in acupuncture, the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists (AACP), and qualified ear acupuncturists trained either in restricted practice NADA and SMART or full ear acupuncture EAR and SAA.

Australia

In Australia, the legalities of practicing acupuncture also vary by state. In 2000, an independent government agency was established to oversee the practice of Chinese Herbal Medicine and Acupuncture in the state of Victoria. The Chinese Medicine Registration Board of Victoria [19] aims to protect the public, ensuring that only appropriately experienced or qualified practitioners are registered to practice Chinese Medicine. The legislation put in place stipulates that only practitioners who are state registered may use the following titles: Acupuncture, Chinese Medicine, Chinese Herbal Medicine, Registered Acupuncturist, Registered Chinese Medicine Practitioner, and Registered Chinese Herbal Medicine Practitioner.

The Parliamentary Committee on the Health Care Complaints Commission in the Australian state of New South Wales commissioned a report investigating Traditional Chinese medicine practice. [20] They recommended the introduction of a government appointed registration board that would regulate the profession by restricting use of the titles "acupuncturist", "Chinese herbal medicine practitioner" and "Chinese medicine practitioner". The aim of registration is to protect the public from the risks of acupuncture by ensuring a high baseline level of competency and education of registered acupuncturists, enforcing guidelines regarding continuing professional education and investigating complaints of practitioner conduct. The registration board will hold more power than local councils in respect to enforcing compliance with legal requirements and investigating and punishing misconduct. Victoria is the only state of Australia with an operational registration board. [21] Currently acupuncturists in NSW are bound by the guidelines in the Public Health (Skin Penetration) Regulation 2000 [22]which is enforced at local council level. Other states of Australia have their own skin penetration acts. The act describes explicitly that single-use disposable needles should be used wherever possible, and that a needle labelled as "single-use" should be disposed of in a sharps container and never reused. Any other type of needle that penetrates the skin should be appropriately sterilised (by autoclave) before reuse.

Many other countries do not license acupuncturists or require them be trained.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acupuncture. |

- Acupoint therapy

- Acupressure

- Acupuncture detoxification

- Auriculotherapy

- Chin na

- Chinese martial arts

- Dragon Rises College of Oriental Medicine

- Electroacupuncture

- Felix Mann

- Medical acupuncture

- Qi

- Qigong

- Seitai

- Susuk

- T'ai Chi Ch'uan

- Traditional Chinese medicine

- Trigger point

Bibliography

- Vincent CA, Richardson PH (1986). "The evaluation of therapeutic acupuncture: concepts and methods". Pain. 24 (1): 1–13. PMID 3513094.

- Richardson PH, Vincent CA (1986). "Acupuncture for the treatment of pain". Pain. 24: 1540.

- Ter Riet G; et al. (1989). "The effectiveness of acupuncture". Huisarts Wet. 32: 170–175, 176–181, 308–312.

- Brinkhaus B, Hummelsberger J, Kohnen R; et al. (2004). "Acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine in the treatment of patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized-controlled clinical trial". Allergy. 59 (9): 953–60. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00540.x. PMID 15291903.

- G. Maciocia. The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists. Second Edition. Churchill Livingstone. 1989

- P. Deadman, K. Baker, M. Al-Khafaji. A Manual of Acupuncture. Eastland Press

- Witt C, Brinkhaus B, Jena S; et al. (2005). "Acupuncture in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised trial". Lancet. 366 (9480): 136–43. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66871-7. PMID 16005336.

- Edwards, J. Acupuncture and Heart Health. Access, February 2002

- Wolfe HL (August/September 2005). "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Acupuncture and its related modalities" (Reprint at findarticles.com). Townsend Letter for Doctors and Patients. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Abuaisha BB, Costanzi JB, Boulton AJ (1998). "Acupuncture for the treatment of chronic painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy: a long-term study". Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 39 (2): 115–21. PMID 9597381.

- Altshul, Sara. "Incontinence: Finally, Relief That Works." Prevention December 2005: 33. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. 30 January 2006

- Deluze C, Bosia L, Zirbs A, Chantraine A, Vischer TL (1992). "Electroacupuncture in fibromyalgia: results of a controlled trial". BMJ. 305 (6864): 1249–52. PMID 1477566.

- Cademartori, Lorraine. "Facing the Point." Forbes October 2005: 85. Academic Search

- Ouyang H, Chen JD (2004). "Review article: therapeutic roles of acupuncture in functional gastrointestinal disorders". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 20 (8): 831–41. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02196.x. PMID 15479354.

- Teng, Liang-yüeh; Chʻeng, Hsin-nung (1987). Chinese acupuncture and moxibustion. Beijing: Foreign Language Press. ISBN 7-119-00378-X.

- Helms JM (1987). "Acupuncture for the management of primary dysmenorrhea". Obstetrics and gynecology. 69 (1): 51–6. PMID 3540764.

- Jin, Guanyuan, Xiang, Jia-Jia and Jin, Lei: Clinical Reflexology of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (Chinese). Beijing Science and Technology Press, Beijing, 2004. ISBN 7-5304-2862-4

- Jin, Guan-Yuan, Jin, Jia-Jia X. and Jin, Louis L.: Contemporary Medical Acupuncture - A Systems Approach (English). Springer, USA & Higher Education Press, PRC, 2006. ISBN 7-04-019257-8

- Kaptchuk, Ted J. (1983). The web that has no weaver: understanding Chinese medicine. New York, N.Y: Congdon & Weed. ISBN 0-86553-109-9.

- Premier. EBSCO. 30 January 2006

- "History of Acupuncture in China." Acupuncture Care. 2 February 2006 <http://www.acupuncturecare.com/acupunct.htm>

- Howard, Cori. "An Ancient Helper for Making a Baby." Maclean’s 23 January 2006: 40. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. 30 January 2006

- Carter B (July 4th, 2007). "Is Acupuncture Safe?". ArticlesLog.com. Retrieved 2007-07-20. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Health Professions Regulatory Advisory Council, Minister’s Referral Letter January 18, 2006 – Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) <http://www.hprac.org/english/projects.asp> 20 March 2006

- Porkert, Manfred (1974). The theoretical foundations of Chinese medicine: systems of correspondence. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-16058-7.

- Wu MT, Hsieh JC, Xiong J; et al. (1999). "Central nervous pathway for acupuncture stimulation: localization of processing with functional MR imaging of the brain--preliminary experience". Radiology. 212 (1): 133–41. PMID 10405732.

Footnotes

- ↑ Lee A, Done ML (2004). "Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub2. PMID 15266478.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy". Bandolier. 59: 4. 1999. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC; et al. (2005). "Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD001351. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001351.pub2. PMID 15674876.

- ↑ Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, Forys K, Ernst E (2005). "Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain" (PDF). Ann. Intern. Med. 142 (8): 651–63. PMID 15838072.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Trinh K, Graham N, Gross A, Goldsmith C, Wang E, Cameron I, Kay T (2007). "Acupuncture for neck disorders". Spine. 32 (2): 236–43. PMID 17224820.

Trinh KV, Graham N, Gross AR; et al. (2006). "Acupuncture for neck disorders". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004870.pub3. - ↑ The Cochrane Collaboration - Acupuncture for idiopathic headache. Melchart D, Linde K, Berman B, White A, Vickers A, Allais G, Brinkhaus B

- ↑ Williams, William F. (2000). Encyclopedia of pseudoscience. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-3351-X.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 NIH Consensus Development Program (November 3–5, 1997). "Acupuncture --Consensus Development Conference Statement". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Get the Facts, Acupuncture". National Institute of Health. 2006. Retrieved 2006-03-02.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Ernst G, Strzyz H, Hagmeister H (2003). "Incidence of adverse effects during acupuncture therapy-a multicentre survey". Complementary therapies in medicine. 11 (2): 93–7. PMID 12801494.

- ↑ Felix Mann: "...acupuncture points are no more real than the black spots that a drunkard sees in front of his eyes." (Mann F. Reinventing Acupuncture: A New Concept of Ancient Medicine. Butterworth Heinemann, London, 1996,14.) Quoted by Matthew Bauer in Chinese Medicine Times, Vol 1 Issue 4 - Aug 2006, "The Final Days of Traditional Beliefs? - Part One"

- ↑ Kaptchuk, 1983, pp. 34-35

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lewith GT, White PJ, Pariente J (2005). "Investigating acupuncture using brain imaging techniques: the current state of play". Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. 2 (3): 315–9. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh110. PMID 16136210. Retrieved 2007-03-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Medical Acupuncture - Spring / Summer 2000- Volume 12 / Number 1

- ↑ Felix Mann, quoted by Matthew Bauer in Chinese Medicine Times, vol 1 issue 4, Aug. 2006, "The Final Days of Traditional Beliefs? - Part One"

- ↑ Skeptic's Dictionary on pseudoscience.

- ↑ Skeptic's Dictionary on acupuncture.

- ↑ Sampson, Wallace Sampson (1996). "Traditional Medicine and Pseudoscience in China: A Report of the Second CSICOP Delegation (Part 2)". Skeptical Inquirer. 20 (5). Retrieved 2007-01-06. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Ulett GA, Acupuncture update 1984, Southern Medical Journal 78:233234, 1985. Comment found at NCBI - Traditional and evidence-based acupuncture: history, mechanisms, and present status. Ulett GA, Han J, Han S.

- ↑ http://www.moondragon.org/health/therapy/acupuncture.html

- ↑ http://www.paralumun.com/acupuncture.htm

- ↑ Medical Acupuncture Review: Safety, Efficacy, And Treatment Practices. Steven E. Braverman, MD

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 The World Health Organization Viewpoint On Acupuncture

- ↑ Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhoea. Proctor ML, Smith CA, Farquhar CM, Stones RW

- ↑ Pomeranz B, Chiu D (1976). "Naloxone blockade of acupuncture analgesia: endorphin implicated". Life Sci. 19 (11): 1757–62. PMID 187888.

- ↑ Mayer DJ, Price DD, Rafii A (1977). "Antagonism of acupuncture analgesia in man by the narcotic antagonist naloxone". Brain Res. 121 (2): 368–72. PMID 832169.

- ↑ Eriksson SV, Lundeberg T, Lundeberg S (1991). "Interaction of diazepam and naloxone on acupuncture induced pain relief". Am. J. Chin. Med. 19 (1): 1–7. PMID 1654741.

- ↑ Bishop B. - Pain: its physiology and rationale for management. Part III. Consequences of current concepts of pain mechanisms related to pain management. Phys Ther. 1980, 60:24-37.

- ↑ Sandrew BB, Yang RC, Wang SC (1978). "Electro-acupuncture analgesia in monkeys: a behavioral and neurophysiological assessment". Archives internationales de pharmacodynamie et de thérapie. 231 (2): 274–84. PMID 417686.

- ↑ Melzack R, Stillwell DM, Fox EJ (1977). "Trigger points and acupuncture points for pain: correlations and implications". Pain. 3 (1): 3–23. PMID 69288.

- ↑ Li K, Shan B, Xu J; et al. (2006). "Changes in FMRI in the human brain related to different durations of manual acupuncture needling". Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.). 12 (7): 615–23. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.12.615. PMID 16970531.

- ↑ Pariente J, White P, Frackowiak RS, Lewith G (2005). "Expectancy and belief modulate the neuronal substrates of pain treated by acupuncture". Neuroimage. 25 (4): 1161–7. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.016. PMID 15850733.

- ↑ Shen J (2001). "Research on the neurophysiological mechanisms of acupuncture: review of selected studies and methodological issues". Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.). 7 Suppl 1: S121–7. doi:10.1089/107555301753393896. PMID 11822627.

- ↑ Liu JL, Han XW, Su SN (1990). "The role of frontal neurons in pain and acupuncture analgesia". Sci. China, Ser. B, Chem. Life Sci. Earth Sci. 33 (8): 938–45. PMID 2242217.

- ↑ Tsuchiya M, Sato EF, Inoue M, Asada A (2007). "Acupuncture enhances generation of nitric oxide and increases local circulation". Anesth. Analg. 104 (2): 301–7. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000230622.16367.fb. PMID 17242084.

- ↑ Blom M, Lundeberg T, Dawidson I, Angmar-Månsson B (1993). "Effects on local blood flux of acupuncture stimulation used to treat xerostomia in patients suffering from Sjögren's syndrome". Journal of oral rehabilitation. 20 (5): 541–8. PMID 10412476.

- ↑ Lundeberg T (1993). "Peripheral effects of sensory nerve stimulation (acupuncture) in inflammation and ischemia". Scandinavian journal of rehabilitation medicine. Supplement. 29: 61–86. PMID 8122077.

- ↑ Okmedi.net: The Bonghan Theory by Kim, Bong-Han

- ↑ HS Shin, HM Johng, BC Lee, S Cho, KS Soh, KY Baik, JS Yoo, KS Soh, Feulgen reaction study of novel threadlike structures (Bonghan ducts) on the surfaces of mammalian organs, Anatomical record. Part B New anatomist, 284(1), pp. 35-40, 2005. (Feature article)

- ↑ Biomedical Physics Laboratory for Korean Medicine, School of Physics, Seoul National University, South Korea. This lab. studies on the Bonghan system.

- ↑ Tonelli MR, Callahan TC (2001). "Why alternative medicine cannot be evidence-based". Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 76 (12): 1213–20. PMID 11739043.

- ↑ Melchart D, Streng A, Hoppe A; et al. (2005). "Acupuncture in patients with tension-type headache: randomised controlled trial". BMJ. 331 (7513): 376–82. doi:10.1136/bmj.38512.405440.8F. PMID 16055451.

- ↑ Tang JL, Zhan SY, Ernst E (1999). "Review of randomised controlled trials of traditional Chinese medicine". BMJ. 319 (7203): 160–1. PMID 10406751.

- ↑ Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC; et al. (2005). "Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD001351. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001351.pub2. PMID 15674876.

- ↑ Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, Forys K, Ernst E (2005). "Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain" (PDF). Ann. Intern. Med. 142 (8): 651–63. PMID 15838072.

- ↑ Lee A, Done ML (2004). "Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub2. PMID 15266478.

- ↑ Ezzo JM, Richardson MA, Vickers A; et al. (2006). "Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD002285. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002285.pub2. PMID 16625560.

- ↑ "Non-pharmacological techniques prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting". Bandolier. 71: 9. 2000. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Kimball C, Atwood IV (2004-05). "The P6 Acupuncture Point and Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting". Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine. 8 (2). Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help); Check date values in:|year=(help) - ↑ Mayhew E, Ernst E (2007). "Acupuncture for fibromyalgia--a systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 46 (5): 801–4. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kel406. PMID 17189243.

- ↑ Message to complementary and alternative medicine: evidence is a better friend than power. Andrew J Vickers

- ↑ "Report 12 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (A-97) -- Alternative Medicine". American Medical Association. 1997.

- ↑ Haake M, Müller HH, Schade-Brittinger C; et al. (2007). "German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for Chronic Low Back Pain: Randomized, Multicenter, Blinded, Parallel-Group Trial With 3 Groups". Arch. Intern. Med. 167 (17): 1892–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.17.1892. PMID 17893311.

- ↑ BBC NEWS, Acupuncture 'best for back pain'

- ↑ Lao L, Hamilton GR, Fu J, Berman BM (2003). "Is acupuncture safe? A systematic review of case reports". Alternative therapies in health and medicine. 9 (1): 72–83. PMID 12564354.

- ↑ Norheim AJ (1996). "Adverse effects of acupuncture: a study of the literature for the years 1981-1994". Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.). 2 (2): 291–7. PMID 9395661.

- ↑ Leow TK (2001). "Pneumothorax Using Bladder 14". Medical Acupuncture. 16 (2).

External links

af:Akupunktuur ar:إبر صينية bg:Акупунктура cs:Akupunktura da:Akupunktur de:Akupunktur et:Akupunktuur eo:Akupunkturo fa:طب سوزنی gl:Acupuntura id:Akupunktur it:Agopuntura he:דיקור סיני lt:Akupunktūra nl:Acupunctuur no:Akupunktur sk:Akupunktúra sl:Akupunktura fi:Akupunktio sv:Akupunktur uk:Акупунктура