Epididymitis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

OMIM = | | OMIM = | | ||

MedlinePlus = | | MedlinePlus = | | ||

MeshID = D004823 | | MeshID = D004823 | | ||

}} | }} | ||

Revision as of 14:07, 15 August 2011

| Epididymitis | |

| |

|---|---|

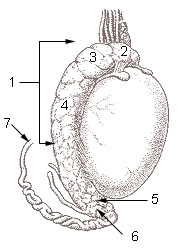

| 1: Epididymis 2: Head of epididymis 3: Lobules of epididymis 4: Body of epididymis 5: Tail of epididymis 6: Duct of epididymis 7: Deferent duct (ductus deferens or vas deferens) | |

| ICD-10 | N45.0 |

| ICD-9 | 604 |

| DiseasesDB | 4342 |

| MeSH | D004823 |

Template:Search infobox Steven C. Campbell, M.D., Ph.D.

Please Join in Editing This Page and Apply to be an Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [1] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Epididymitis is a medical condition in which there is inflammation of the epididymis (a curved structure at the back of the testicle in which sperm matures and is stored). This condition may be mildly to very painful, and the scrotum (sac containing the testicles) may become red, warm and swollen. It may be acute (of sudden onset) or rarely chronic.

Epididymitis is the most frequent cause of scrotal pain. In contrast with men who have testicular torsion, the cremaster reflex (elevation of the testicle in respons to stroking the upper inner thigh) is not altered. If the diagnosis is not entirely clear from the patient's history and physical examination, a Doppler ultrasound scan can confirm increased flow of blood to the affected epididymis.

Infection is the most common cause. In sexually active men, Chlamydia trachomatis is the most frequent causative microbe, followed by E. coli and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In children, it may follow an infection in another part of the body (for example, a viral illness), or there may be an associated urinary tract anomaly. Another cause is sterile reflux of urine through the ejaculatory ducts. Antibiotics may be needed to control a component of infection. Treatment otherwise comprises pain killers or anti-inflammatory drugs and bed rest if necessary, and symptom control by resting the scrotum in a supported position.

Causes

Infection is the most common cause of epididymitis. The bacteria in the urethra back-track through the urinary and reproductive structures to the epididymis. There can be associated urethritis (inflammation of the urethra). Rarely, the infection reaches the epididymis via the bloodstream.

In sexually active men, Chlamydia trachomatis is responsible for two-thirds of cases, followed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and E. coli (or other bacteria that cause urinary tract infection). Less common microbes include Ureaplasma, Mycobacterium, and cytomegalovirus, or Cryptococcus in patients with HIV infection. E. coli is more common in boys before puberty, the elderly and homosexual men.

Non-infectious causes are also possible. Reflux of sterile urine (urine without bacteria) through the ejaculatory ducts may cause inflammation with obstruction. In children, it may be a response following an infection with enterovirus, adenovirus or Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

Epididymitis can also be caused by genito-urinary surgery, including prostatectomy and urinary catheterization. Congestive epididymitis is a long-term complication of vasectomy.[1][2] Chemical epididymitis may also result from drugs such as amiodarone.[3]

Diagnosis

Epididymitis can be hard to distinguish from testicular torsion. Both can occur at the same time. A urologist may need to be consulted.

Epididymitis usually has a gradual onset. On physical examination, the testicle is usually found to be in its normal vertical position, of equal size compared to its counterpart, and not high-riding. Typical findings are redness, warmth and swelling of the scrotum, with tenderness behind the testicle, away from the middle (this is the normal position of the epididymis relative to the testicle). The cremasteric reflex (if it was normal before) remains normal. This is a useful sign to distinguish it from testicular torsion. If there is pain relieved by elevation of the testicle, this is called Prehn's sign, which is however non-specific.

Analysis of the urine may or may not be normal. Before the advent of sophisticated medical imaging techniques, surgical exploration was the standard of care. Nowadays, color Doppler ultrasound is the preferred test. It can demonstrated increased blood flow (also compared to the normal side), as opposed to testicular torsion. Nuclear testicular blood flow testing is rarely used.

Additional tests may be necessary to identify underlying causes. In younger children, a urinary tract anomaly is frequently found. In sexually active men, tests for sexually transmitted diseases may be done. These may include microscopy and culture of a first void urine sample, Gram stain and culture of fluid or a swab from the urethra, nuclear acid amplification tests (to amplify and detect microbial DNA or other nucleic acids) or tests for syphillis and HIV.

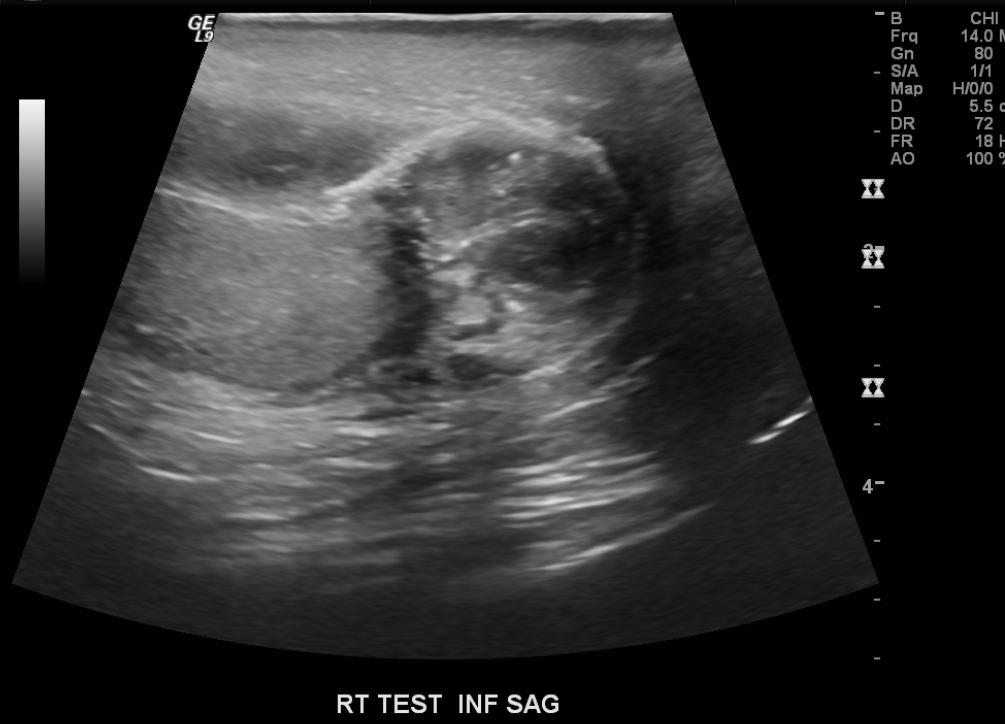

Ultrasound

- The epididymal head is the most affected region, and reactive hydrocele and wall thickening are frequently present.

- Increased size and, depending on the time of evolution, decreased, increased, or heterogeneous echogenicity of the affected organ are usually observed.

- The inflammation produces increased blood flow within the epididymis, testis, or both.

- Analysis of the epididymal waveform may reveal a low-resistance pattern as compared with the normal pattern.

MRI

-

Severe epididymitis with focal abscess formation

-

Severe epididymitis with focal abscess formation

-

Severe epididymitis with focal abscess formation

Complications

Most cases with adequate treatment develop no complications and don't result in infertility. Untreated, acute epididymitis can lead to a variety of complications. These include chronic epididymitis, abscess, permanent damage or even destruction of the epididymis and testicle (resulting in infertility and/or hypogonadism), and infection may spread to any other organ or system of the body.

Treatment

Antibiotics are used if an infection is suspected. Fluoroquinolones are an option, although resistance of N. gonorrhoeae may limit their use. A cephalosporin (such as ceftriaxone) combined with doxycycline is an alternative. Azithromycin can be used for susceptible strains. In children, quinolones and doxycycline are best avoided. Since bacteria that cause urinary tract infections are often the cause of epididymitis in children, co-trimoxazole or suited penicillins (for example, cephalexin) can be used. If there is a sexually transmitted disease, the partner should also be treated.

Household remedies such as elevation of the scrotum and cold compresses applied regularly to the scrotum may relieve the pain. Painkillers or anti-inflammatory drugs are often necessary. Hospitalisation is indicated for severe cases, and check-ups can ensure the infection has cleared up. Surgery is rarely necessary, for example in those rare instances where an abscess forms.

Chronic epididymitis

Chronic epididymitis is epididymitis which ensues for more than six weeks. Chronic epididymitis is characterised by inflammation even when there is no infection present. Tests are needed to distinguish chronic epididymitis from a range of other disorders that can cause constant scrotal pain. These include testicular cancer, enlarged scrotal veins (varicocele) or a cyst within the epididymis. As well, the nerves in the scrotal area are connected to those of the abdomen, sometimes causing pain similar to a hernia (see referred pain). This condition can develop even without the presence of the previously described known causes.

Typically, a second, longer round of treatment is used. It is believed that the hypersensitivity of certain structures, including nerves and muscles, may cause or contribute to chronic epididymitis. A procedure called a cord block is a last measure. This consists of an injection into the nerve that traces along the epididymis. The injection is a compound of several medications including a steroid, pain killers, and a high dose of an anti-inflammatory. This treatment can quell the pain for 2-3 months in ideal conditions. Some patients may only experience an even shorter duration of 2-3 days, while the fortunate ones in rare occasions are never bothered again. This procedure would of course have to be repeated when necessary, until the problem goes away completely, or until the routine is simply too bothersome. As a last resort, a patient may then decide to have the epididymis completely removed.

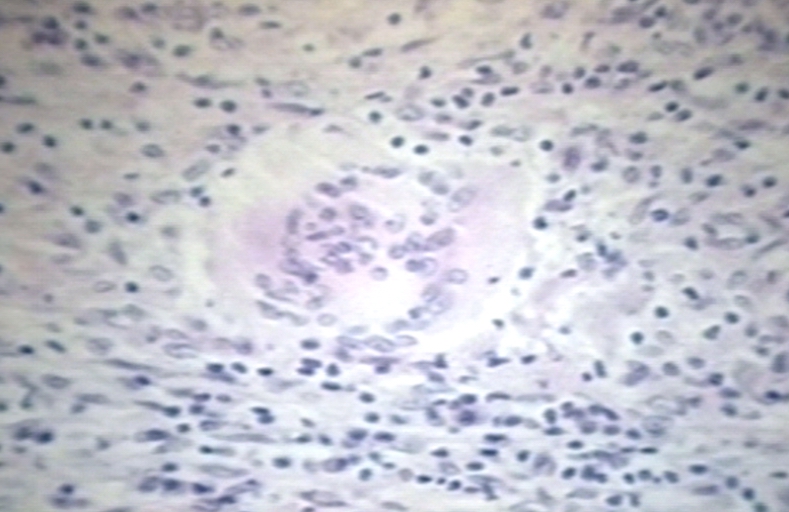

Pathological Findings

-

Testes: Epididymitis, Chronic; Inflammation Centered on Epididymal Tubules

-

Testes: Epididymitis with Sperm Granulomas; Note Dystrophic Calcification

References

- ↑ Schwingl PJ, Guess HA (2000). "Safety and effectiveness of vasectomy". Fertil. Steril. 73 (5): 923–36. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00482-9. PMID 10785217.

- ↑ Raspa RF (1993). "Complications of vasectomy". American family physician. 48 (7): 1264–8. PMID 8237740.

- ↑ Ibsen HH, Frandsen F, Brandrup F, Møller M (1989). "Epididymitis caused by treatment with amiodarone". Genitourin Med. 65 (4): 257–8. PMID 2807285. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) PMC 1194364

See Also

Further reading

- Galejs LE (1999). "Diagnosis and treatment of the acute scrotum". Am Fam Physician. 59 (4): 817–24. PMID 10068706. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - Nickel JC (2003). "Chronic epididymitis: a practical approach to understanding and managing a difficult urologic enigma". Rev Urol. 5 (4): 209–15. PMID 16985840. PMC 1553215

- Celestino Aso, Goya Enríquez, Marta Fité, Nuria Torán, Carmen Piró, Joaquim Piqueras, and Javier Lucaya. Gray-Scale and Color Doppler Sonography of Scrotal Disorders in Children: An Update. RadioGraphics 2005 25: 1197-1214.

- Paula J. Woodward, Cornelia M. Schwab, and Isabell A. Sesterhenn. From the Archives of the AFIP: Extratesticular Scrotal Masses: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. RadioGraphics 2003 23: 215-240.

External links

Template:Diseases of the pelvis, genitals and breasts Template:SIB

de:Epididymitis it:Epididimite nl:Epididymo-orchitis simple:Epididymitis sv:bitestikelinflammation