Celiac disease pathophysiology: Difference between revisions

m (Bot: Removing from Primary care) |

|||

| (97 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{| class="infobox mw-collapsible" id="floatvideo" style="position: fixed; top: 65%; width:361px; right: 10px; margin: 0 0 0 0; border: 0; float: right;" | |||

| Title | |||

|- | |||

|- | |||

| {{#ev:youtube|https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nXzBApAx5lY|350}} | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

{{Celiac disease}} | {{Celiac disease}} | ||

{{CMG}} | {{CMG}} ;{{AE}} {{MMF}} | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

The etiology of the celiac disease is known to be multifactorial, both in that multiple factors can lead to the disease and that multiple factors are necessary for the disease to manifest in a patient. [[Gluten]] triggers autoimmunity and results in the inflammation of the gastrointestinal mucosa. [[Gluten]] in wheat, rye, and barley may trigger the [[autoimmunity]] to develop celiac disease. [[Gluten]] peptides cross the epithelium into the [[lamina propria]] where they are [[Deamination|deamidated]] by tissue [[transglutaminase]]. The peptides are then presented by DQ2+ or DQ8+ antigen-presenting cells to pathogenic CD4+ T cells. The CD4+ T cells trigger the T-helper-cell type 1 response which results in the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the [[lamina propria]] and epithelium. This inflammatory process ultimately leads to [[Crypt (anatomy)|crypt]] hyperplasia and [[Intestinal villus|villous]] atrophy. It is suggested that the [[gliadin]] may be responsible for the primary manifestations of celiac disease whereas tTG is a bigger factor in secondary effects such as allergic responses and secondary [[autoimmune disease]]. Over 95% of celiac patients have an isoform of [[HLA DQ|DQ2]] (encoded by DQA1*05 and DQB1*02 genes) and [[HLA-DQ8|DQ8]] (encoded by the [[haplotype]] DQA1*03:DQB1*0302), which is inherited in families. The reason these genes produce an increased risk of celiac disease is that the receptors formed by these genes bind to [[gliadin]] peptides more tightly than other forms of the antigen-presenting receptor. Therefore, these forms of the receptor are more likely to activate [[T cell|T lymphocytes]] and initiate the autoimmune process. Celiac disease is associated with other [[autoimmune diseases]] such as [[Diabetes mellitus type 1|type 1 diabetes mellitus]], [[IgA deficiency]], [[IgA nephropathy]], [[insulin dependent diabetes mellitus|insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM)]], [[Sjogren’s syndrome]], [[juvenile idiopathic arthritis]], [[juvenile rheumatoid arthritis]], [[Hashimoto's thyroiditis]], [[Graves' disease|Graves Disease]], and [[dermatitis herpetiformis]]. | |||

==Pathophysiology== | ==Pathophysiology== | ||

The etiology of the celiac disease is known to be multifactorial, both in that more than one abnormal factor can lead to the disease and also more than one factor is necessary for the disease to manifest in a patient. [[Gluten]] triggers autoimmunity and results in the inflammation of the gastrointestinal mucosa.<ref name="pmid14570737">{{cite journal |vauthors=Lundin KE, Nilsen EM, Scott HG, Løberg EM, Gjøen A, Bratlie J, Skar V, Mendez E, Løvik A, Kett K |title=Oats induced villous atrophy in coeliac disease |journal=Gut |volume=52 |issue=11 |pages=1649–52 |year=2003 |pmid=14570737 |pmc=1773854 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Størsrud S, Olsson M, Arvidsson Lenner R, Nilsson L, Nilsson O, Kilander A | title = Adult coeliac patients do tolerate large amounts of oats | journal = Eur J Clin Nutr | volume = 57 | issue = 1 | pages = 163-9 | year = 2003 | id = PMID 12548312|url= http://www.nature.com/ejcn/journal/v57/n1/abs/1601525a.html}}</ref> | |||

*Prolamines are storage proteins with a similar [[amino acid]] composition to the [[gliadin]] fractions of wheat. [[Proline|Prolines]] have been identified in barley (hordeins) and rye (secalines), and are related closely to the properties of wheat cereal that affect people with celiac disease. | |||

*Wheat varieties or sub-types containing gluten such as spelt and the rye/wheat hybrid triticale may also trigger the symptoms of celiac disease. | |||

*[[Gluten]] is mainly found in wheat. [[Gluten]] consists of storage proteins that remain after starch is washed from wheat-flour dough. | |||

*These storage proteins have different solubilities in alcohol–water solutions and are usually separated into two fractions: | |||

**[[Gliadin|Gliadins]] | |||

**[[Gluten|Glutenins]] | |||

*Gluten proteins are grouped into four main types (ω5-, ω1,2-, α/β-, γ-[[Gliadin|gliadins]]). | |||

*Several [[gliadin]] [[epitopes]] are [[Immunogenicity|immunogenic]] and also have direct toxic effects. | |||

===Pathogenesis=== | |||

[[Gluten]] in wheat, rye, and barley may trigger the [[autoimmunity]] to develop celiac disease. [[Gluten]] peptides cross the epithelium into the [[lamina propria]] where they are [[Deamination|deamidated]] by tissue [[transglutaminase]]. The peptides are then presented by DQ2+ or DQ8+ antigen-presenting cells to pathogenic CD4+ T cells. The CD4+ T cells trigger the T-helper-cell type 1 response which results in the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lamina propria and epithelium. This inflammatory process ultimately leads to [[Crypt (anatomy)|crypt]] hyperplasia and [[Intestinal villus|villous]] atrophy.<ref name="pmid19394538">{{cite journal |vauthors=Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR |title=Coeliac disease |journal=Lancet |volume=373 |issue=9673 |pages=1480–93 |year=2009 |pmid=19394538 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60254-3 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid19394538">{{cite journal |vauthors=Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR |title=Coeliac disease |journal=Lancet |volume=373 |issue=9673 |pages=1480–93 |year=2009 |pmid=19394538 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60254-3 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid16125764">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ciclitira PJ, Johnson MW, Dewar DH, Ellis HJ |title=The pathogenesis of coeliac disease |journal=Mol. Aspects Med. |volume=26 |issue=6 |pages=421–58 |year=2005 |pmid=16125764 |doi=10.1016/j.mam.2005.05.001 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid14592529">{{cite journal |vauthors=Dewar D, Pereira SP, Ciclitira PJ |title=The pathogenesis of coeliac disease |journal=Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=17–24 |year=2004 |pmid=14592529 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid19443237">{{cite journal |vauthors=Heap GA, van Heel DA |title=Genetics and pathogenesis of coeliac disease |journal=Semin. Immunol. |volume=21 |issue=6 |pages=346–54 |year=2009 |pmid=19443237 |doi=10.1016/j.smim.2009.04.001 |url=}}</ref> | |||

==== Epithelial translocation of gluten peptides==== | |||

The gluten peptides can be translocated through the gastric epithelium via these mechanisms: | |||

*[[Paracellular transport]] | |||

*[[Transcytosis|Transcytosis transport]] | |||

*Retrotranscytosis transport | |||

==== Modification of gluten peptides==== | |||

The [[gluten]] peptides are deaminated by the [[Tissue transglutaminase|tissue transglutaminas]]<nowiki/>e (tTG) to glutamic acid molecules. Tissue transglutaminase is cross linked to the [[Deamination|deaminated]] gluten. | |||

==== Antigenic presentation of gluten peptides==== | |||

The [[glutamic acid]] molecules cross-linked with tTG are presented to CD4+ T cells. | |||

=== | ==== Inflammatory reaction==== | ||

The activation of [[CD4+ T cells|CD4+ T cell]] produces several proinflammatory cytokines which may trigger the secretion of tissue-damaging matrix metalloproteinases and activation of lymphocytes against the enterocytes which result in [[enterocyte]] [[apoptosis]] and villous flattening. | |||

*Alternative causes of this tissue damage have been proposed and involve the release of [[interleukin 15]] and activation of the innate immune system by a shorter gluten peptide (p31–43/49). This triggers the killing of [[enterocytes]] by lymphocytes in the epithelium. | |||

= | |||

The | |||

===Tissue transglutaminase=== | ===Tissue transglutaminase=== | ||

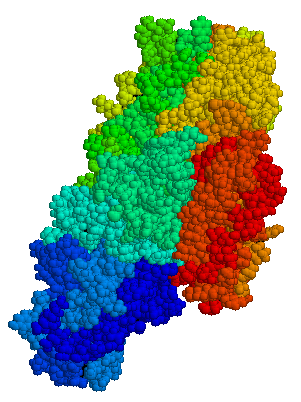

[[Image:Tissue transglutaminase.png|thumb|left| | [[Image:Tissue transglutaminase.png|thumb|left|100px|[[Tissue transglutaminase]], Source: {{PDB|1FAU}}.]] | ||

[[Anti-transglutaminase antibodies]] to the enzyme [[tissue transglutaminase]] (tTG) are found in an overwhelming majority of cases.<ref name=Dieterich>{{cite journal | author = Dieterich W, Ehnis T, Bauer M, Donner P, Volta U, Riecken E, Schuppan D | title = Identification of tissue transglutaminase as the autoantigen of celiac disease | journal = Nat Med | volume = 3 | issue = 7 | pages = 797–801 | year = 1997 | id = PMID 9212111}}</ref> | [[Anti-transglutaminase antibodies]] to the enzyme [[tissue transglutaminase]] (tTG) are found in an overwhelming majority of cases. Tissue transglutaminase modifies gluten [[peptide]]s into a form that may stimulate the immune system more effectively.<ref name="Dieterich">{{cite journal | author = Dieterich W, Ehnis T, Bauer M, Donner P, Volta U, Riecken E, Schuppan D | title = Identification of tissue transglutaminase as the autoantigen of celiac disease | journal = Nat Med | volume = 3 | issue = 7 | pages = 797–801 | year = 1997 | id = PMID 9212111}}</ref> | ||

*Endomysial component of antibodies (EMA) to tTG are believed to be directed towards cell surface transglutaminase.<ref name="EMAnegCD">{{cite journal |author=Salmi T, Collin P, Korponay-Szabó I, Laurila K, Partanen J, Huhtala H, Király R, Lorand L, Reunala T, Mäki M, Kaukinen K |title=Endomysial antibody-negative coeliac disease: clinical characteristics and intestinal autoantibody deposits |journal=Gut |volume=55 |issue=12 |pages=1746–53 |year=2006 |pmid=16571636}}</ref> | |||

*It is suggested that the gliadin may be responsible for the primary manifestations of celiac disease whereas tTG is a bigger factor in secondary effects such as allergic responses and secondary [[autoimmune disease]]<nowiki/>s.<ref name="InnateReview">{{cite journal | author = Londei M, Ciacci C, Ricciardelli I, Vacca L, Quaratino S, and Maiuri L. | title = Gliadin as a stimulator of innate responses in celiac disease | journal = Mol Immunol | volume = 42 | issue = 8 | pages = 913–918 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15829281}}</ref> | |||

*Stored biopsies from suspected celiac patients have revealed that [[autoantibody]] deposits in the [[Wiktionary:subclinical|subclinical]] gastrointestinal mucosal lining of celiacs are detected prior to clinical disease. These deposits are also found in patients who present with other [[Autoimmune disease|autoimmune diseases]], [[anemia]] or [[malabsorption]] phenomena at an increased rate compared to the normal population.<ref name="Kaukinen">{{cite journal | author = Kaukinen K, Peraaho M, Collin P, Partanen J, Woolley N, Kaartinen T, Nuuntinen T, Halttunen T, Maki M, Korponay-Szabo I | title = Small-bowel mucosal transglutaminase 2-specific IgA deposits in coeliac disease without villous atrophy: A Prospective and randomized clinical study | journal = Scand J Gastroenterology | volume = 40 | pages = 564–572 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 16036509}}</ref> | |||

=== | ===VP7 protein=== | ||

*In a large percentage of celiac patients, the [[Anti-transglutaminase antibodies|anti-tTG antibodies]] also recognize a [[rotavirus]] protein called VP7. These antibodies stimulate monocyte proliferation and rotavirus infection might explain some early steps in the cascade of immune cell proliferation. Indeed, earlier studies of [[rotavirus]] damage in the gut showed this causes a villous atrophy.<ref name="toll-like">{{cite journal |author=Zanoni G, Navone R, Lunardi C, Tridente G, Bason C, Sivori S, Beri R, Dolcino M, Valletta E, Corrocher R, Puccetti A |title=In celiac disease, a subset of autoantibodies against transglutaminase binds toll-like receptor 4 and induces activation of monocytes |journal=PLoS Med |volume=3 |issue=9 |pages=e358 |year=2006 |pmid=16984219}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Salim A, Phillips A, Farthing M | title = Pathogenesis of gut virus infection | journal = Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol | volume = 4 | issue = 3 | pages = 593–607 | year = 1990 | id = PMID 1962725}}</ref> | |||

*This suggests that viral proteins may take part in the initial flattening and stimulate self-reactive anti-VP7 production. Antibodies to VP7 may also slow healing until the [[gliadin]] mediated tTG presentation provides a second source of self-reactive antibodies. | |||

==Genetics== | |||

HLA and non-HLA genes are involved in the pathogenesis of the celiac disease<ref name="pmid19394538">{{cite journal |vauthors=Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR |title=Coeliac disease |journal=Lancet |volume=373 |issue=9673 |pages=1480–93 |year=2009 |pmid=19394538 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60254-3 |url=}}</ref>.<ref name="pmid17785484">{{cite journal |author=Hadithi M, von Blomberg BM, Crusius JB, ''et al'' |title=Accuracy of serologic tests and HLA-DQ typing for diagnosing celiac disease |journal=Ann. Intern. Med. |volume=147 |issue=5 |pages=294–302 |year=2007 |pmid=17785484 |doi=|url=http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/147/5/294}}</ref> | |||

*HLA [[genes]] are a part of the [[major histocompatibility complex|MHC class II antigen-presenting receptor]] (also called the [[human leukocyte antigen]]) system and distinguish between self and non-self antigens for the [[immune system]]. There are 7 HLA DQ variants (DQ2 and DQ4 through 9). | |||

*[[HLA-DQ2|DQ2]] and [[HLA-DQ8|DQ8]] are associated with celiac disease. The gene is located on the short arm of the [[Chromosome 6 (human)|sixth chromosome]], and as a result of the [[genetic linkage|linkage]], this [[locus (genetics)|locus]] has been labeled as CELIAC1. | |||

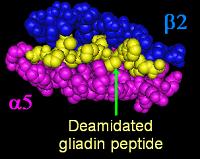

Over 95% of | *Over 95% of celiac patients have an isoform of [[HLA DQ|DQ2]] (encoded by DQA1*05 and DQB1*02 genes) and [[HLA-DQ8|DQ8]] (encoded by the [[haplotype]] DQA1*03:DQB1*0302), which is inherited in families. The reason these genes produce an increased risk of celiac disease is that the receptors formed by these genes bind to [[gliadin]] peptides more tightly than other forms of the antigen-presenting receptor. Therefore, these forms of the receptor are more likely to activate [[T cell|T lymphocytes]] and initiate the autoimmune process. | ||

[[Image:DQa2b5_da_gliadin.jpg|frame|left|DQ α<sup>5</sup>-β<sup>2</sup> -binding cleft with a deamidated gliadin peptide (yellow), modified from {{PDB|1S9V}}<ref>{{cite journal | author = Kim C, Quarsten H, Bergseng E, Khosla C, Sollid L | title = Structural basis for HLA-DQ2-mediated presentation of gluten epitopes in celiac disease | journal = Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A | volume = 101 | issue = 12 | pages = 4175–9 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15020763}}</ref> ]] | [[Image:DQa2b5_da_gliadin.jpg|frame|left|DQ α<sup>5</sup>-β<sup>2</sup> -binding cleft with a deamidated gliadin peptide (yellow), modified from {{PDB|1S9V}}<ref>{{cite journal | author = Kim C, Quarsten H, Bergseng E, Khosla C, Sollid L | title = Structural basis for HLA-DQ2-mediated presentation of gluten epitopes in celiac disease | journal = Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A | volume = 101 | issue = 12 | pages = 4175–9 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15020763}}</ref> ]] | ||

Most | *Most celiac patients bear a two-gene [[HLA-DQ]] [[haplotype]] referred to as [[HLA-DQ2#DQ2.5|DQ2.5 haplotype]]. This haplotype is composed of 2 adjacent gene [[allele]]s, DQA1*0501 and [[HLA-DQ2#DQB1.2A0201|DQB1*0201]], which encode the two subunits, DQ α<sup>5</sup> and DQ β<sup>2</sup>. In most individuals, the DQ2.5 isoform is encoded by one of two [[Chromosome 6 (human)|chromosomes 6]] inherited from parents. Most celiacs inherit only one copy of the DQ2.5 haplotype, while some inherit it from ''both'' parents; the latter are especially at risk of celiac disease, as well as being more susceptible to severe complications.<ref name="pmid17190762">{{cite journal | author = Jores RD, Frau F, Cucca F, ''et al'' | title = HLA-DQB1*0201 homozygosis predisposes to severe intestinal damage in celiac disease | journal = Scand. J. Gastroenterol. | volume = 42 | issue = 1 | pages = 48-53 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17190762 | doi = 10.1080/00365520600789859}}</ref> | ||

*Some individuals inherit DQ2.5 from one parent and portions of the haplotype ([[HLA-DQ|DQB1*02]] or DQA1*05) from the other parent, increasing risk. Less commonly, some individuals inherit the DQA1*05 allele from one parent and the DQB1*02 from the other parent, called a trans-haplotype association, and these individuals are at similar risk for the development of celiac disease as those with a single DQ2.5 bearing chromosome 6, but in this case, the disease tends to be non-familial.<ref name="pmid12651074">{{cite journal |author=Karell K, Louka AS, Moodie SJ, ''et al'' |title=HLA types in celiac disease patients not carrying the DQA1*05-DQB1*02 (DQ2) heterodimer: results from the European Genetics Cluster on Celiac Disease |journal=Hum. Immunol. |volume=64 |issue=4 |pages=469-77 |year=2003 |pmid=12651074 |doi= |issn=}}</ref> | |||

*In addition to the CELIAC1 locus, CELIAC2 ([[Chromosome 5 (human)|5]]q31-q33 - IBD5 locus), CELIAC3 ([[Chromosome 2 (human)|2]]q33 -CTLA4 locus), CELIAC4 ([[Chromosome 19 (human)|19]]p13.1 - MYOIXB locus), have been linked to coeliac disease. The [[CTLA4]] and [[myosin IXB]] and gene have been found to be linked to celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases.<ref name="pmid16025348">{{cite journal | author = Zhernakova A, Eerligh P, Barrera P, ''et al'' | title = CTLA4 is differentially associated with autoimmune diseases in the Dutch population | journal = Hum. Genet. | volume = 118 | issue = 1 | pages = 58-66 | year = 2005 | pmid = 16025348 | doi = 10.1007/s00439-005-0006-z}}</ref><ref name="pmid17584584">{{cite journal | author = Sánchez E, Alizadeh BZ, Valdigem G, ''et al'' | title = MYO9B gene polymorphisms are associated with autoimmune diseases in Spanish population | journal = Hum. Immunol. | volume = 68 | issue = 7 | pages = 610-5 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17584584 | doi = 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.03.006}}</ref> Two additional loci on [[Chromosome 4 (human)|chromosome 4]], 4q27 (IL2 or IL21 locus) and 4q14, have been found to be linked to coeliac disease.<ref name="pmid17558408">{{cite journal | author = van Heel DA, Franke L, Hunt KA, ''et al'' | title = A genome-wide association study for celiac disease identifies risk variants in the region harboring IL2 and IL21 | journal = Nat Genet | volume = 39 | issue = 7 | pages = 827-9 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17558408 | doi = 10.1038/ng2058}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Popat S, Bevan S, Braegger C, Busch A, O'Donoghue D, Falth-Magnusson K, Godkin A, Hogberg L, Holmes G, Hosie K, Howdle P, Jenkins H, Jewell D, Johnston S, Kennedy N, Kumar P, Logan R, Love A, Marsh M, Mulder C, Sjoberg K, Stenhammar L, Walker-Smith J, Houlston R | title = Genome screening of coeliac disease | journal = J Med Genet | volume = 39 | issue = 5 | pages = 328-31 | year = 2002 | url = http://jmg.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/39/5/328 | id = PMID 12011149}}</ref> | |||

== Associated Conditions == | |||

==== | Celiac disease is associated with other autoimmune diseases which include:<ref name="pmid12578508">{{cite journal |vauthors=Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, Not T, Colletti RB, Drago S, Elitsur Y, Green PH, Guandalini S, Hill ID, Pietzak M, Ventura A, Thorpe M, Kryszak D, Fornaroli F, Wasserman SS, Murray JA, Horvath K |title=Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study |journal=Arch. Intern. Med. |volume=163 |issue=3 |pages=286–92 |year=2003 |pmid=12578508 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid15825127">{{cite journal |vauthors=Murray JA |title=Celiac disease in patients with an affected member, type 1 diabetes, iron-deficiency, or osteoporosis? |journal=Gastroenterology |volume=128 |issue=4 Suppl 1 |pages=S52–6 |year=2005 |pmid=15825127 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="urlCo-occurrence of celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases in celiacs and their first-degree relatives - ScienceDirect">{{cite web |url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0896841108000759 |title=Co-occurrence of celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases in celiacs and their first-degree relatives - ScienceDirect |format= |work= |accessdate=}}</ref><ref name="pmid9290622">{{cite journal |vauthors=Cataldo F, Marino V, Bottaro G, Greco P, Ventura A |title=Celiac disease and selective immunoglobulin A deficiency |journal=J. Pediatr. |volume=131 |issue=2 |pages=306–8 |year=1997 |pmid=9290622 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="urlwww.omicsonline.org">{{cite web |url=https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/gluten-transglutaminase-celiac-disease-and-iga-nephropathy-2155-9899-1000499.php?aid=88489 |title=www.omicsonline.org |format= |work= |accessdate=}}</ref><ref name="pmid19394538">{{cite journal |vauthors=Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR |title=Coeliac disease |journal=Lancet |volume=373 |issue=9673 |pages=1480–93 |year=2009 |pmid=19394538 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60254-3 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid26303674">{{cite journal |vauthors=Lundin KE, Wijmenga C |title=Coeliac disease and autoimmune disease-genetic overlap and screening |journal=Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol |volume=12 |issue=9 |pages=507–15 |year=2015 |pmid=26303674 |doi=10.1038/nrgastro.2015.136 |url=}}</ref> | ||

*[[Diabetes mellitus type 1|Type 1 diabetes mellitus]] | |||

*[[IgA deficiency]] | |||

*[[IgA nephropathy]] | |||

* [[Insulin dependent diabetes mellitus|Insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM)]] | |||

* [[Sjogren’s syndrome]] | |||

*[[Juvenile idiopathic arthritis]] | |||

*[[Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis]] | |||

*[[Hashimoto's thyroiditis]] | |||

*[[Graves' disease|Graves Disease]] | |||

*[[Dermatitis herpetiformis]] | |||

*[[Primary sclerosing cholangitis]] | |||

*[[Autoimmune hepatitis]] | |||

*[[Irritable bowel syndrome]] | |||

*[[Down's syndrome]] | |||

*[[Turner syndrome]] | |||

===Pathology | ==Gross Pathology== | ||

The classic | On gross pathology, duodenum usually shows:<ref name="pmid24355936">{{cite journal |vauthors=Schuppan D, Zimmer KP |title=The diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease |journal=Dtsch Arztebl Int |volume=110 |issue=49 |pages=835–46 |year=2013 |pmid=24355936 |pmc=3884535 |doi=10.3238/arztebl.2013.0835 |url=}}</ref> | ||

*Scalloping of duodenal folds | |||

*Mosaic mucosal pattern | |||

*Mucosal atrophy | |||

==Microscopic Pathology== | |||

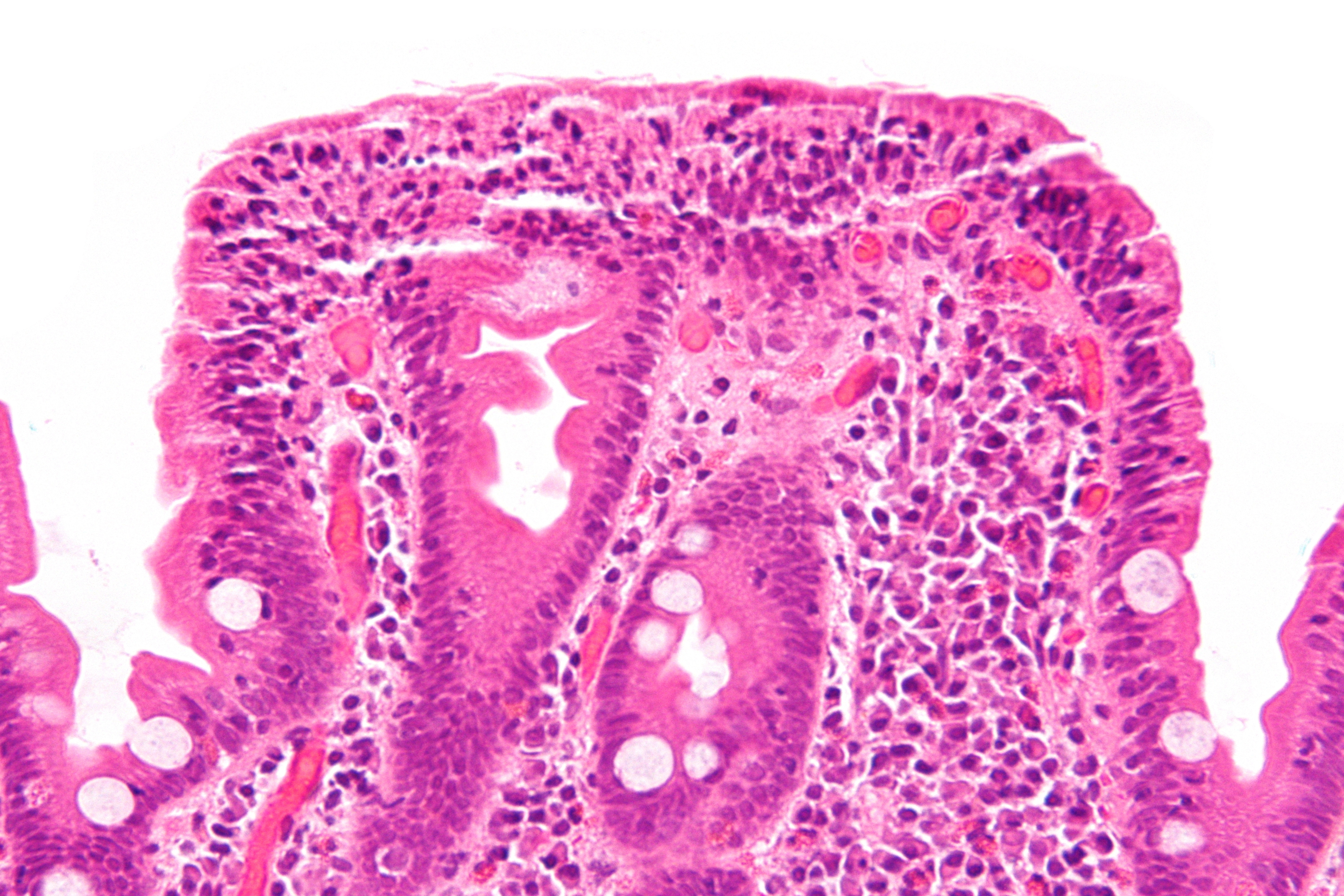

The classic pathological changes of celiac disease in the small bowel are categorized by the "Marsh classification":<ref name="pmid24355936">{{cite journal |vauthors=Schuppan D, Zimmer KP |title=The diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease |journal=Dtsch Arztebl Int |volume=110 |issue=49 |pages=835–46 |year=2013 |pmid=24355936 |pmc=3884535 |doi=10.3238/arztebl.2013.0835 |url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid1727768">{{cite journal |author=Marsh MN |title=Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity ('celiac sprue') |journal=[[Gastroenterology]] |volume=102 |issue=1 |pages=330–54 |year=1992 |month=January |pmid=1727768 |doi= |url=}}</ref> | |||

*Marsh stage 0: normal mucosa | *Marsh stage 0: normal mucosa | ||

*Marsh stage 1: increased number of | *Marsh stage 1: increased number of intraepithelial [[lymphocytes]], usually exceeding 20 per 100 [[enterocyte]]s | ||

*Marsh stage 2: proliferation of the [[crypts of Lieberkuhn]] | *Marsh stage 2: proliferation of the [[crypts of Lieberkuhn]] | ||

*Marsh stage 3: partial or complete [[intestinal villus|villous]] [[atrophy]] | *Marsh stage 3: partial or complete [[intestinal villus|villous]] [[atrophy]] | ||

*Marsh stage 4: [[hypoplasia]] of the [[small bowel]] architecture | *Marsh stage 4: [[hypoplasia]] of the [[small bowel]] architecture | ||

[[File:Celiac disease - very high mag.jpg|left|thumb|250px|A histological photgraph of intestinal villi in celiac disease; '''Villious atrophy'''. Image courtest:By Nephron - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27188726]] | |||

<br clear="left" /> | |||

= | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 79: | Line 108: | ||

{{WH}} | {{WH}} | ||

{{WS}} | {{WS}} | ||

[[Category:Disease]] | |||

[[Category:Gastroenterology]] | |||

[[Category:Rheumatology]] | |||

[[Category:Autoimmune diseases]] | |||

[[Category:Genetic disorders]] | |||

[[Category:Malnutrition]] | |||

[[Category:Pediatrics]] | |||

[[Category:Dermatology]] | |||

[[Category:Up-To-Date]] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:51, 29 July 2020

| Title |

| https://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nXzBApAx5lY%7C350}} |

|

Celiac disease Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Medical Therapy |

|

Case Studies |

|

Celiac disease pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Celiac disease pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Celiac disease pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] ;Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Furqan M M. M.B.B.S[2]

Overview

The etiology of the celiac disease is known to be multifactorial, both in that multiple factors can lead to the disease and that multiple factors are necessary for the disease to manifest in a patient. Gluten triggers autoimmunity and results in the inflammation of the gastrointestinal mucosa. Gluten in wheat, rye, and barley may trigger the autoimmunity to develop celiac disease. Gluten peptides cross the epithelium into the lamina propria where they are deamidated by tissue transglutaminase. The peptides are then presented by DQ2+ or DQ8+ antigen-presenting cells to pathogenic CD4+ T cells. The CD4+ T cells trigger the T-helper-cell type 1 response which results in the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lamina propria and epithelium. This inflammatory process ultimately leads to crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy. It is suggested that the gliadin may be responsible for the primary manifestations of celiac disease whereas tTG is a bigger factor in secondary effects such as allergic responses and secondary autoimmune disease. Over 95% of celiac patients have an isoform of DQ2 (encoded by DQA1*05 and DQB1*02 genes) and DQ8 (encoded by the haplotype DQA1*03:DQB1*0302), which is inherited in families. The reason these genes produce an increased risk of celiac disease is that the receptors formed by these genes bind to gliadin peptides more tightly than other forms of the antigen-presenting receptor. Therefore, these forms of the receptor are more likely to activate T lymphocytes and initiate the autoimmune process. Celiac disease is associated with other autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes mellitus, IgA deficiency, IgA nephropathy, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), Sjogren’s syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Graves Disease, and dermatitis herpetiformis.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of the celiac disease is known to be multifactorial, both in that more than one abnormal factor can lead to the disease and also more than one factor is necessary for the disease to manifest in a patient. Gluten triggers autoimmunity and results in the inflammation of the gastrointestinal mucosa.[1][2]

- Prolamines are storage proteins with a similar amino acid composition to the gliadin fractions of wheat. Prolines have been identified in barley (hordeins) and rye (secalines), and are related closely to the properties of wheat cereal that affect people with celiac disease.

- Wheat varieties or sub-types containing gluten such as spelt and the rye/wheat hybrid triticale may also trigger the symptoms of celiac disease.

- Gluten is mainly found in wheat. Gluten consists of storage proteins that remain after starch is washed from wheat-flour dough.

- These storage proteins have different solubilities in alcohol–water solutions and are usually separated into two fractions:

- Gluten proteins are grouped into four main types (ω5-, ω1,2-, α/β-, γ-gliadins).

- Several gliadin epitopes are immunogenic and also have direct toxic effects.

Pathogenesis

Gluten in wheat, rye, and barley may trigger the autoimmunity to develop celiac disease. Gluten peptides cross the epithelium into the lamina propria where they are deamidated by tissue transglutaminase. The peptides are then presented by DQ2+ or DQ8+ antigen-presenting cells to pathogenic CD4+ T cells. The CD4+ T cells trigger the T-helper-cell type 1 response which results in the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lamina propria and epithelium. This inflammatory process ultimately leads to crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy.[3][3][4][5][6]

Epithelial translocation of gluten peptides

The gluten peptides can be translocated through the gastric epithelium via these mechanisms:

- Paracellular transport

- Transcytosis transport

- Retrotranscytosis transport

Modification of gluten peptides

The gluten peptides are deaminated by the tissue transglutaminase (tTG) to glutamic acid molecules. Tissue transglutaminase is cross linked to the deaminated gluten.

Antigenic presentation of gluten peptides

The glutamic acid molecules cross-linked with tTG are presented to CD4+ T cells.

Inflammatory reaction

The activation of CD4+ T cell produces several proinflammatory cytokines which may trigger the secretion of tissue-damaging matrix metalloproteinases and activation of lymphocytes against the enterocytes which result in enterocyte apoptosis and villous flattening.

- Alternative causes of this tissue damage have been proposed and involve the release of interleukin 15 and activation of the innate immune system by a shorter gluten peptide (p31–43/49). This triggers the killing of enterocytes by lymphocytes in the epithelium.

Tissue transglutaminase

Anti-transglutaminase antibodies to the enzyme tissue transglutaminase (tTG) are found in an overwhelming majority of cases. Tissue transglutaminase modifies gluten peptides into a form that may stimulate the immune system more effectively.[7]

- Endomysial component of antibodies (EMA) to tTG are believed to be directed towards cell surface transglutaminase.[8]

- It is suggested that the gliadin may be responsible for the primary manifestations of celiac disease whereas tTG is a bigger factor in secondary effects such as allergic responses and secondary autoimmune diseases.[9]

- Stored biopsies from suspected celiac patients have revealed that autoantibody deposits in the subclinical gastrointestinal mucosal lining of celiacs are detected prior to clinical disease. These deposits are also found in patients who present with other autoimmune diseases, anemia or malabsorption phenomena at an increased rate compared to the normal population.[10]

VP7 protein

- In a large percentage of celiac patients, the anti-tTG antibodies also recognize a rotavirus protein called VP7. These antibodies stimulate monocyte proliferation and rotavirus infection might explain some early steps in the cascade of immune cell proliferation. Indeed, earlier studies of rotavirus damage in the gut showed this causes a villous atrophy.[11][12]

- This suggests that viral proteins may take part in the initial flattening and stimulate self-reactive anti-VP7 production. Antibodies to VP7 may also slow healing until the gliadin mediated tTG presentation provides a second source of self-reactive antibodies.

Genetics

HLA and non-HLA genes are involved in the pathogenesis of the celiac disease[3].[13]

- HLA genes are a part of the MHC class II antigen-presenting receptor (also called the human leukocyte antigen) system and distinguish between self and non-self antigens for the immune system. There are 7 HLA DQ variants (DQ2 and DQ4 through 9).

- DQ2 and DQ8 are associated with celiac disease. The gene is located on the short arm of the sixth chromosome, and as a result of the linkage, this locus has been labeled as CELIAC1.

- Over 95% of celiac patients have an isoform of DQ2 (encoded by DQA1*05 and DQB1*02 genes) and DQ8 (encoded by the haplotype DQA1*03:DQB1*0302), which is inherited in families. The reason these genes produce an increased risk of celiac disease is that the receptors formed by these genes bind to gliadin peptides more tightly than other forms of the antigen-presenting receptor. Therefore, these forms of the receptor are more likely to activate T lymphocytes and initiate the autoimmune process.

- Most celiac patients bear a two-gene HLA-DQ haplotype referred to as DQ2.5 haplotype. This haplotype is composed of 2 adjacent gene alleles, DQA1*0501 and DQB1*0201, which encode the two subunits, DQ α5 and DQ β2. In most individuals, the DQ2.5 isoform is encoded by one of two chromosomes 6 inherited from parents. Most celiacs inherit only one copy of the DQ2.5 haplotype, while some inherit it from both parents; the latter are especially at risk of celiac disease, as well as being more susceptible to severe complications.[15]

- Some individuals inherit DQ2.5 from one parent and portions of the haplotype (DQB1*02 or DQA1*05) from the other parent, increasing risk. Less commonly, some individuals inherit the DQA1*05 allele from one parent and the DQB1*02 from the other parent, called a trans-haplotype association, and these individuals are at similar risk for the development of celiac disease as those with a single DQ2.5 bearing chromosome 6, but in this case, the disease tends to be non-familial.[16]

- In addition to the CELIAC1 locus, CELIAC2 (5q31-q33 - IBD5 locus), CELIAC3 (2q33 -CTLA4 locus), CELIAC4 (19p13.1 - MYOIXB locus), have been linked to coeliac disease. The CTLA4 and myosin IXB and gene have been found to be linked to celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases.[17][18] Two additional loci on chromosome 4, 4q27 (IL2 or IL21 locus) and 4q14, have been found to be linked to coeliac disease.[19][20]

Associated Conditions

Celiac disease is associated with other autoimmune diseases which include:[21][22][23][24][25][3][26]

- Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- IgA deficiency

- IgA nephropathy

- Insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM)

- Sjogren’s syndrome

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- Hashimoto's thyroiditis

- Graves Disease

- Dermatitis herpetiformis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Down's syndrome

- Turner syndrome

Gross Pathology

On gross pathology, duodenum usually shows:[27]

- Scalloping of duodenal folds

- Mosaic mucosal pattern

- Mucosal atrophy

Microscopic Pathology

The classic pathological changes of celiac disease in the small bowel are categorized by the "Marsh classification":[27][28]

- Marsh stage 0: normal mucosa

- Marsh stage 1: increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes, usually exceeding 20 per 100 enterocytes

- Marsh stage 2: proliferation of the crypts of Lieberkuhn

- Marsh stage 3: partial or complete villous atrophy

- Marsh stage 4: hypoplasia of the small bowel architecture

References

- ↑ Lundin KE, Nilsen EM, Scott HG, Løberg EM, Gjøen A, Bratlie J, Skar V, Mendez E, Løvik A, Kett K (2003). "Oats induced villous atrophy in coeliac disease". Gut. 52 (11): 1649–52. PMC 1773854. PMID 14570737.

- ↑ Størsrud S, Olsson M, Arvidsson Lenner R, Nilsson L, Nilsson O, Kilander A (2003). "Adult coeliac patients do tolerate large amounts of oats". Eur J Clin Nutr. 57 (1): 163–9. PMID 12548312.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR (2009). "Coeliac disease". Lancet. 373 (9673): 1480–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60254-3. PMID 19394538.

- ↑ Ciclitira PJ, Johnson MW, Dewar DH, Ellis HJ (2005). "The pathogenesis of coeliac disease". Mol. Aspects Med. 26 (6): 421–58. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2005.05.001. PMID 16125764.

- ↑ Dewar D, Pereira SP, Ciclitira PJ (2004). "The pathogenesis of coeliac disease". Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36 (1): 17–24. PMID 14592529.

- ↑ Heap GA, van Heel DA (2009). "Genetics and pathogenesis of coeliac disease". Semin. Immunol. 21 (6): 346–54. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2009.04.001. PMID 19443237.

- ↑ Dieterich W, Ehnis T, Bauer M, Donner P, Volta U, Riecken E, Schuppan D (1997). "Identification of tissue transglutaminase as the autoantigen of celiac disease". Nat Med. 3 (7): 797–801. PMID 9212111.

- ↑ Salmi T, Collin P, Korponay-Szabó I, Laurila K, Partanen J, Huhtala H, Király R, Lorand L, Reunala T, Mäki M, Kaukinen K (2006). "Endomysial antibody-negative coeliac disease: clinical characteristics and intestinal autoantibody deposits". Gut. 55 (12): 1746–53. PMID 16571636.

- ↑ Londei M, Ciacci C, Ricciardelli I, Vacca L, Quaratino S, and Maiuri L. (2005). "Gliadin as a stimulator of innate responses in celiac disease". Mol Immunol. 42 (8): 913–918. PMID 15829281.

- ↑ Kaukinen K, Peraaho M, Collin P, Partanen J, Woolley N, Kaartinen T, Nuuntinen T, Halttunen T, Maki M, Korponay-Szabo I (2005). "Small-bowel mucosal transglutaminase 2-specific IgA deposits in coeliac disease without villous atrophy: A Prospective and randomized clinical study". Scand J Gastroenterology. 40: 564–572. PMID 16036509.

- ↑ Zanoni G, Navone R, Lunardi C, Tridente G, Bason C, Sivori S, Beri R, Dolcino M, Valletta E, Corrocher R, Puccetti A (2006). "In celiac disease, a subset of autoantibodies against transglutaminase binds toll-like receptor 4 and induces activation of monocytes". PLoS Med. 3 (9): e358. PMID 16984219.

- ↑ Salim A, Phillips A, Farthing M (1990). "Pathogenesis of gut virus infection". Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 4 (3): 593–607. PMID 1962725.

- ↑ Hadithi M, von Blomberg BM, Crusius JB; et al. (2007). "Accuracy of serologic tests and HLA-DQ typing for diagnosing celiac disease". Ann. Intern. Med. 147 (5): 294–302. PMID 17785484.

- ↑ Kim C, Quarsten H, Bergseng E, Khosla C, Sollid L (2004). "Structural basis for HLA-DQ2-mediated presentation of gluten epitopes in celiac disease". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101 (12): 4175–9. PMID 15020763.

- ↑ Jores RD, Frau F, Cucca F; et al. (2007). "HLA-DQB1*0201 homozygosis predisposes to severe intestinal damage in celiac disease". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 42 (1): 48–53. doi:10.1080/00365520600789859. PMID 17190762.

- ↑ Karell K, Louka AS, Moodie SJ; et al. (2003). "HLA types in celiac disease patients not carrying the DQA1*05-DQB1*02 (DQ2) heterodimer: results from the European Genetics Cluster on Celiac Disease". Hum. Immunol. 64 (4): 469–77. PMID 12651074.

- ↑ Zhernakova A, Eerligh P, Barrera P; et al. (2005). "CTLA4 is differentially associated with autoimmune diseases in the Dutch population". Hum. Genet. 118 (1): 58–66. doi:10.1007/s00439-005-0006-z. PMID 16025348.

- ↑ Sánchez E, Alizadeh BZ, Valdigem G; et al. (2007). "MYO9B gene polymorphisms are associated with autoimmune diseases in Spanish population". Hum. Immunol. 68 (7): 610–5. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2007.03.006. PMID 17584584.

- ↑ van Heel DA, Franke L, Hunt KA; et al. (2007). "A genome-wide association study for celiac disease identifies risk variants in the region harboring IL2 and IL21". Nat Genet. 39 (7): 827–9. doi:10.1038/ng2058. PMID 17558408.

- ↑ Popat S, Bevan S, Braegger C, Busch A, O'Donoghue D, Falth-Magnusson K, Godkin A, Hogberg L, Holmes G, Hosie K, Howdle P, Jenkins H, Jewell D, Johnston S, Kennedy N, Kumar P, Logan R, Love A, Marsh M, Mulder C, Sjoberg K, Stenhammar L, Walker-Smith J, Houlston R (2002). "Genome screening of coeliac disease". J Med Genet. 39 (5): 328–31. PMID 12011149.

- ↑ Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, Not T, Colletti RB, Drago S, Elitsur Y, Green PH, Guandalini S, Hill ID, Pietzak M, Ventura A, Thorpe M, Kryszak D, Fornaroli F, Wasserman SS, Murray JA, Horvath K (2003). "Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (3): 286–92. PMID 12578508.

- ↑ Murray JA (2005). "Celiac disease in patients with an affected member, type 1 diabetes, iron-deficiency, or osteoporosis?". Gastroenterology. 128 (4 Suppl 1): S52–6. PMID 15825127.

- ↑ "Co-occurrence of celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases in celiacs and their first-degree relatives - ScienceDirect".

- ↑ Cataldo F, Marino V, Bottaro G, Greco P, Ventura A (1997). "Celiac disease and selective immunoglobulin A deficiency". J. Pediatr. 131 (2): 306–8. PMID 9290622.

- ↑ "www.omicsonline.org".

- ↑ Lundin KE, Wijmenga C (2015). "Coeliac disease and autoimmune disease-genetic overlap and screening". Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 12 (9): 507–15. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.136. PMID 26303674.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Schuppan D, Zimmer KP (2013). "The diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 110 (49): 835–46. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2013.0835. PMC 3884535. PMID 24355936.

- ↑ Marsh MN (1992). "Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity ('celiac sprue')". Gastroenterology. 102 (1): 330–54. PMID 1727768. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)