High density lipoprotein physiology

|

High Density Lipoprotein Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Clinical Trials |

|

Case Studies |

|

High density lipoprotein physiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of High density lipoprotein physiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for High density lipoprotein physiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Ayokunle Olubaniyi, M.B,B.S [2]

Overview

The physiology of HDL centers around the reverse cholesterol transport system. Nascent HDLs secreted into the plasma by the liver or intestines pick up free cholesterol from peripheral tissues and the arterial wall mediated mainly by the ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1). The enzyme LCAT (lecithin-cholesteryl acetyltransferase) catalyzes the esterification of the free cholesterol, and also converts the nascent HDLs into mature forms. The esterified cholesterol is transported to the liver where CETP (cholesterylester transfer protein), an enzyme produced in the liver, acts on it transferring the cholesterol to other apo B containing lipoproteins. The cholesterol-deplete HDLs get broken down by triglyceride lipases into apo A-I which either takes up free cholesterol to continue the cycle, or gets eliminated in the kidney. In addition to HDL being atheroprotective against cardiovascular diseases, it also exhibits anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, anti-coagulant, vasodilatory, and metabolic properties.

HDL Metabolism

The metabolism of HDL can also be described as the Reverse Cholesterol Transport System. HDL serves a mode of transportation for the excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the liver.

Shown below is an image depicting HDL metabolism. Refer to the text below for further explanation.

Adopted from Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. ABCA1= ATP-binding cassette transporter A1; ABCG1: ATP-binding cassette transporter G1; ABCG4: ATP-binding cassette transporter G4; ApoA-I= Apolipoprotein A-I; CETP: Cholesteryl transfer protein; LCAT: Lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase; SRBI: Scavenger receptor, class B, type I. [1]

Synthesis and Uptake of Cholesterol

- HDL consists majorly of apo A-I and/or apo A-II. Both the liver and the small intestine synthesize apo A-I while only the liver synthesizes apo A-II. HDL is normally synthesized consisting mainly of phospholipids and apolipoproteins.

- Free apo A-I is released into the plasma as nascent HDLs. This readily takes up excess free cholesterol (FC) from peripheral tissues such as fibroblasts and macrophages and arterial wall mediated by either ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1), G1/G4, scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SR-B1), Cyp27A1, caveloin, and passive diffusion, leading to the formation of discoid HDL (a.k.a. pre-βHDL).

- Apo A-I activates lecithin:cholesteryl acetyltransferase (LCAT) which catalyses the esterification of the free cholesterol bound to the discoid HDL. The Apolipoprotein A1 acts as a signal protein in mobilizing cholesterol esters from within the cells.

aaaaavvvvvvccccccattttttttttttttttttttttttaaaaaaaaaaLCAT

aaaaavvvvvvaaaaaaaaaaaLecithin + Cholesterol ———-> Lysolecithin + Cholesterol ester

Maturation and Transfer of Cholesterol

- The esterified cholesterol moves into the hydrophobic core of the HDL, changing the HDL particle from discoid to spherical (mature HDL). This process also prevents the re-uptake of cholesterol by cells. LCAT is responsible for the maturation of HDL particles.

- The esterified cholesterol can be delivered back to the liver through a number of routes:

- By the action of cholesterylester transfer protein (CETP) - CETP, secreted in the liver, transfers cholesterol from HDL to the apo B–containing lipoproteins e.g., very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) or intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) to be taken up by the liver. Mutations of this transport protein gene causes familial HDL deficiencies and Tangier disease

- HDL particles may be taken up directly by the liver

- Free cholesterol may be taken up directly by the liver

- HDL cholesterol esters may be selectively taken up via the scavenger receptor SR-B1, which is expressed in the liver.

Catabolism

- Triglyceride lipases degrade these cholesterol-deplete HDL particles into small, dense HDL particles which after dissociation, release apo A-I (nascent HDL). The apo A-1 either rapidly re-uptakes free cholesterol again by ABCA1 to form discoid HDLs or it is endocytosed in the kidney tubule or cleared via glomerular filtration.

Functions

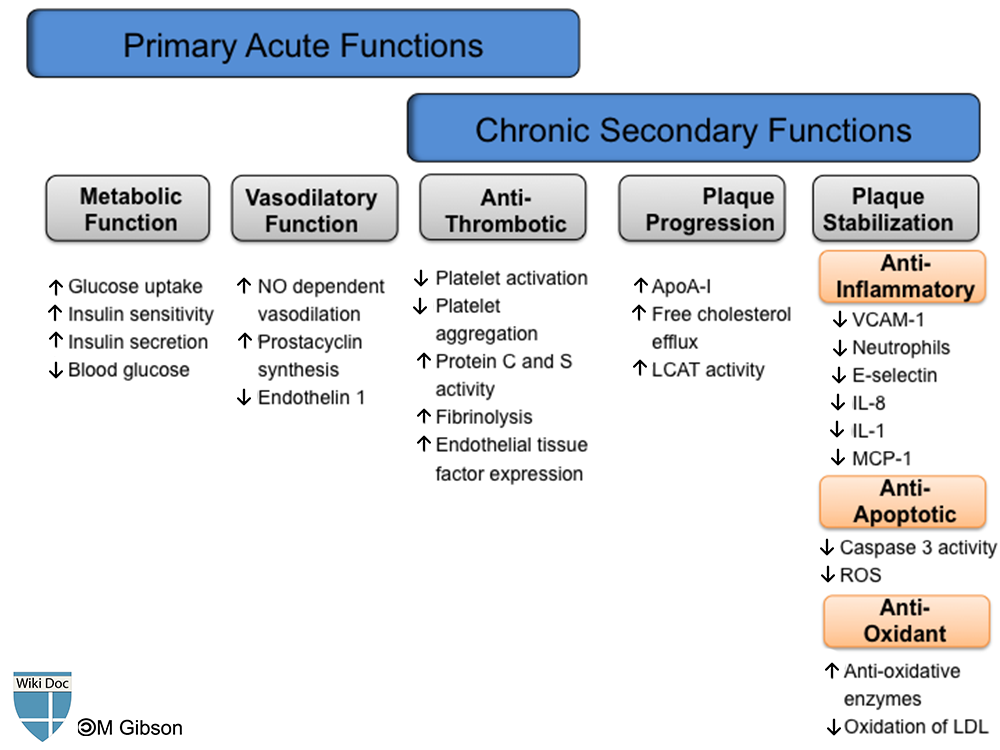

Shown below is an image summarizing the physiologic functions of HDL in an acute and chronic setting. Please refer to the text below for details about each one of functions of HDL.

Atheroprotection

It has been established that HDL-cholesterol has an inverse correlation with future atherosclerotic cardiovascular complications. HDL and apo A-I exhibit many atheroprotective functions which primarily aims at removing cholesterol from peripheral tissues and the arterial wall through various efflux mechanisms, mainly the reverse cholesterol transport system. It is also important in the attenuation of plaque progression and promotion of plaque stabilization. These functions are exhibited through its anti-oxidative, anti-platelet, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory properties. With all these properties in context, HDL will potentially protect against reperfusion ischemic injuries and secondary plaque ruptures frequently observed in post-acute coronary syndrome patients.

- Current data indicate that the plasma HDL associated apolipoprotein M (apoM) levels modulate the ability of plasma to mobilize cellular cholesterol and protects against experimental atherosclerosis.[2]

- Animal models have shown that the somatic gene transfer of human apo A-I can prevent the development of atherosclerosis or reverse preexisting atherosclerosis or its role in the anti-endotoxin function of HDL.[3][4][5][6]

- ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 in endothelial cells, and the scavenger receptor B type I mediate multiple intracellular signaling pathways as well as the efflux of cholesterol.[7]

Anti-coagulant Funtions

HDL has the ability to inhibit platelet activation and aggregation by directly inhibiting platelet activation,[8][9] downregulating thromboxane A2 synthesis,[10] increasing the synthesis of prostacyclin,[11] and lowering the expression of the tissue factor which is required in the coagulation process.[12]

Anti-oxidant Funtions

The formation of free oxygen radicals contributes to the pathogenesis and progression of atherosclerotic plaques. Oxidized LDLs gets engulfed by macrophages, which leads to further oxidation and the production of foam cells. Oxidized LDLs acts as chemotactic agents for circulating monocytes, converts macrophages into foam cells, induce cytotoxic effects on the endothelium, inhibits motility of tissue macrophages, and stimulates the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells.[13] HDL has been shown to inhibit the oxidative modification of oxidized LDLs,[14] as well as preventing their infiltration into the vessel wall.[15]

Anti-inflammatory Functions

HDL has anti-inflammatory functions in both endothelial cells and leukocytes. During inflammation, several leukocyte adhesion molecules are activated which promotes the binding of leukocytes and formation of atheroma. HDL has been shown to inhibit the activation of vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1,[16] interleukin-1-induced expresion of E-selectin,[17] interleukin-8, intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, neutrophils,[18] monocytes,[19] and also prevents the binding of T-lymphocytes to monocytes thereby preventing the formation of pro-inflammatory cytokines.[20]

Metabolic Functions

In a study to determine the effects and mechanisms of HDL on glucose metabolism, 13 type 2 diabetic patients received intravenous reconstituted HDL. The result proved a reduction in the plasma glucose of the patients due to an increase in plasma insulin in addition to the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in skeletal muscle. These findings suggest a role for HDL-raising therapies beyond atherosclerosis to address type 2 diabetes mellitus.[21]

Glucose Metabolism

HDL is postulated to modulate glucose homeostasis through several mechanisms including stimulating insulin secretion,[22][23][21][24] enhancing insulin sensitivity, and increasing glucose update by skeletal muscle via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway and is being recognized as an active player in the pathophysiology of diabetes rather than an onlooker.[25][23] Genetic engineering studies that manipulate expression of related genes such as ABCA1,[26][27][28][29] CETP,[30][31] ABCG1,[32] and apoA-I[25] have provided preliminary evidences indicating crude associations between plasma HDL concentrations and glycemic control. Silencing of microRNA species has also shown to result in upregulation of these target genes along with elevation of functional HDL levels,[33][34][35][36] suggesting an extensively-linked yet fine-tuned state of homeostasis in energy metabolism.

Anti-apoptotic Functions

- Plasma HDLs in-vitro were shown to offer some cytoprotection against oxidized LDL-causing apoptosis and generation of reactive oxygen species.[37]

- HDL also protects endothelial cells from apoptosis and promotes their growth and their migration via SRBI-initiated signaling.[38]

- It is also proposed that the anti-apoptotic and proliferative effects of apoA-I are mediated through F1-ATPase-catalysed ADP production and subsequent P2Y13 receptor stimulation.[39]

Vasodilatory Functions

HDL has been shown to restore endothelial dysfunction which is implicated in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. In a study, reconstituted HDL was infused in patients with type 2 diabetes and the vascular function (forearm blood flow) was assessed at 4 hours and 7 days post-infusion. HDL was found to increase the forearm blood flow in diabetic patients as compared to the controlled group, probably due to its effect on increasing nitric oxide bioavailability.[40]

References

- ↑ Linsel-Nitschke P, Tall AR (2005). "HDL as a target in the treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease". Nat Rev Drug Discov. 4 (3): 193–205. doi:10.1038/nrd1658. PMID 15738977.

- ↑ Elsøe S, Christoffersen C, Luchoomun J, Turner S, Nielsen LB (2013). "Apolipoprotein M promotes mobilization of cellular cholesterol in vivo". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1831 (7): 1287–92. PMID 24046869.

- ↑ Benoit P, Emmanuel F, Caillaud JM, Bassinet L, Castro G, Gallix P; et al. (1999). "Somatic gene transfer of human ApoA-I inhibits atherosclerosis progression in mouse models". Circulation. 99 (1): 105–10. PMID 9884386.

- ↑ Tangirala RK, Tsukamoto K, Chun SH, Usher D, Puré E, Rader DJ (1999). "Regression of atherosclerosis induced by liver-directed gene transfer of apolipoprotein A-I in mice". Circulation. 100 (17): 1816–22. PMID 10534470.

- ↑ Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Hama S, Garber DW, Chaddha M, Hough G; et al. (2002). "Oral administration of an Apo A-I mimetic Peptide synthesized from D-amino acids dramatically reduces atherosclerosis in mice independent of plasma cholesterol". Circulation. 105 (3): 290–2. PMID 11804981.

- ↑ Ma J, Liao XL, Lou B, Wu MP (2004). "Role of apolipoprotein A-I in protecting against endotoxin toxicity". Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 36 (6): 419–24. PMID 15188057.

- ↑ Prosser HC, Ng MK, Bursill CA (2012). "The role of cholesterol efflux in mechanisms of endothelial protection by HDL". Curr Opin Lipidol. 23 (3): 182–9. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e328352c4dd. PMID 22488423.

- ↑ Calkin, AC.; Drew, BG.; Ono, A.; Duffy, SJ.; Gordon, MV.; Schoenwaelder, SM.; Sviridov, D.; Cooper, ME.; Kingwell, BA. (2009). "Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein attenuates platelet function in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus by promoting cholesterol efflux". Circulation. 120 (21): 2095–104. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.870709. PMID 19901191. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Lerch, PG.; Spycher, MO.; Doran, JE. (1998). "Reconstituted high density lipoprotein (rHDL) modulates platelet activity in vitro and ex vivo". Thromb Haemost. 80 (2): 316–20. PMID 9716159. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Brill, A.; Fuchs, TA.; Chauhan, AK.; Yang, JJ.; De Meyer, SF.; Köllnberger, M.; Wakefield, TW.; Lämmle, B.; Massberg, S. (2011). "von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet adhesion is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mouse models". Blood. 117 (4): 1400–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-05-287623. PMID 20959603. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Fleisher, LN.; Tall, AR.; Witte, LD.; Miller, RW.; Cannon, PJ. (1982). "Stimulation of arterial endothelial cell prostacyclin synthesis by high density lipoproteins". J Biol Chem. 257 (12): 6653–5. PMID 7045092. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Viswambharan, H.; Ming, XF.; Zhu, S.; Hubsch, A.; Lerch, P.; Vergères, G.; Rusconi, S.; Yang, Z. (2004). "Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein inhibits thrombin-induced endothelial tissue factor expression through inhibition of RhoA and stimulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase but not Akt/endothelial nitric oxide synthase". Circ Res. 94 (7): 918–25. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000124302.20396.B7. PMID 14988229. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Kita T, Kume N, Minami M, Hayashida K, Murayama T, Sano H; et al. (2001). "Role of oxidized LDL in atherosclerosis". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 947: 199–205, discussion 205-6. PMID 11795267.

- ↑ Parthasarathy S, Barnett J, Fong LG (1990). "High-density lipoprotein inhibits the oxidative modification of low-density lipoprotein". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1044 (2): 275–83. PMID 2344447.

- ↑ Galle, J.; Ochslen, M.; Schollmeyer, P.; Wanner, C. (1994). "Oxidized lipoproteins inhibit endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Effects of pressure and high-density lipoprotein". Hypertension. 23 (5): 556–64. PMID 8175161. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Dimayuga, P.; Zhu, J.; Oguchi, S.; Chyu, KY.; Xu, XO.; Yano, J.; Shah, PK.; Nilsson, J.; Cercek, B. (1999). "Reconstituted HDL containing human apolipoprotein A-1 reduces VCAM-1 expression and neointima formation following periadventitial cuff-induced carotid injury in apoE null mice". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 264 (2): 465–8. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.1278. PMID 10529386. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Cockerill, GW.; Huehns, TY.; Weerasinghe, A.; Stocker, C.; Lerch, PG.; Miller, NE.; Haskard, DO. (2001). "Elevation of plasma high-density lipoprotein concentration reduces interleukin-1-induced expression of E-selectin in an in vivo model of acute inflammation". Circulation. 103 (1): 108–12. PMID 11136694. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Murphy, AJ.; Woollard, KJ.; Suhartoyo, A.; Stirzaker, RA.; Shaw, J.; Sviridov, D.; Chin-Dusting, JP. (2011). "Neutrophil activation is attenuated by high-density lipoprotein and apolipoprotein A-I in in vitro and in vivo models of inflammation". Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 31 (6): 1333–41. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226258. PMID 21474825. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Murphy, AJ.; Woollard, KJ.; Hoang, A.; Mukhamedova, N.; Stirzaker, RA.; McCormick, SP.; Remaley, AT.; Sviridov, D.; Chin-Dusting, J. (2008). "High-density lipoprotein reduces the human monocyte inflammatory response". Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 28 (11): 2071–7. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168690. PMID 18617650. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Carpintero, R.; Gruaz, L.; Brandt, KJ.; Scanu, A.; Faille, D.; Combes, V.; Grau, GE.; Burger, D. (2010). "HDL interfere with the binding of T cell microparticles to human monocytes to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production". PLoS One. 5 (7): e11869. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011869. PMID 20686620.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Drew, BG.; Duffy, SJ.; Formosa, MF.; Natoli, AK.; Henstridge, DC.; Penfold, SA.; Thomas, WG.; Mukhamedova, N.; de Courten, B. (2009). "High-density lipoprotein modulates glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus". Circulation. 119 (15): 2103–11. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.843219. PMID 19349317. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Brunham, LR.; Kruit, JK.; Pape, TD.; Timmins, JM.; Reuwer, AQ.; Vasanji, Z.; Marsh, BJ.; Rodrigues, B.; Johnson, JD. (2007). "Beta-cell ABCA1 influences insulin secretion, glucose homeostasis and response to thiazolidinedione treatment". Nat Med. 13 (3): 340–7. doi:10.1038/nm1546. PMID 17322896. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 23.0 23.1 Abderrahmani, A.; Niederhauser, G.; Favre, D.; Abdelli, S.; Ferdaoussi, M.; Yang, JY.; Regazzi, R.; Widmann, C.; Waeber, G. (2007). "Human high-density lipoprotein particles prevent activation of the JNK pathway induced by human oxidised low-density lipoprotein particles in pancreatic beta cells". Diabetologia. 50 (6): 1304–14. doi:10.1007/s00125-007-0642-z. PMID 17437081. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Fryirs, MA.; Barter, PJ.; Appavoo, M.; Tuch, BE.; Tabet, F.; Heather, AK.; Rye, KA. (2010). "Effects of high-density lipoproteins on pancreatic beta-cell insulin secretion". Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 30 (8): 1642–8. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207373. PMID 20466975. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 25.0 25.1 Han, R.; Lai, R.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, G.; He, J.; Liu, W. (2007). "Apolipoprotein A-I stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase and improves glucose metabolism". Diabetologia. 50 (9): 1960–8. doi:10.1007/s00125-007-0752-7. PMID 17639303. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Vergeer, M.; Brunham, LR.; Koetsveld, J.; Kruit, JK.; Verchere, CB.; Kastelein, JJ.; Hayden, MR.; Stroes, ES. (2010). "Carriers of loss-of-function mutations in ABCA1 display pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction". Diabetes Care. 33 (4): 869–74. doi:10.2337/dc09-1562. PMID 20067955. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Daimon, M.; Kido, T.; Baba, M.; Oizumi, T.; Jimbu, Y.; Kameda, W.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ohnuma, H.; Tominaga, M. (2005). "Association of the ABCA1 gene polymorphisms with type 2 DM in a Japanese population". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 329 (1): 205–10. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.119. PMID 15721294. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Villarreal-Molina, MT.; Flores-Dorantes, MT.; Arellano-Campos, O.; Villalobos-Comparan, M.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M.; Miliar-García, A.; Huertas-Vazquez, A.; Menjivar, M.; Romero-Hidalgo, S. (2008). "Association of the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 R230C variant with early-onset type 2 diabetes in a Mexican population". Diabetes. 57 (2): 509–13. doi:10.2337/db07-0484. PMID 18003760. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Koseki, M.; Matsuyama, A.; Nakatani, K.; Inagaki, M.; Nakaoka, H.; Kawase, R.; Yuasa-Kawase, M.; Tsubakio-Yamamoto, K.; Masuda, D. (2009). "Impaired insulin secretion in four Tangier disease patients with ABCA1 mutations". J Atheroscler Thromb. 16 (3): 292–6. PMID 19556721. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ López-Ríos, L.; Pérez-Jiménez, P.; Martínez-Quintana, E.; Rodriguez González, G.; Díaz-Chico, BN.; Nóvoa, FJ.; Serra-Majem, L.; Chirino, R. (2011). "Association of Taq 1B CETP polymorphism with insulin and HOMA levels in the population of the Canary Islands". Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 21 (1): 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2009.06.009. PMID 19822408. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Zhong, S.; Sharp, DS.; Grove, JS.; Bruce, C.; Yano, K.; Curb, JD.; Tall, AR. (1996). "Increased coronary heart disease in Japanese-American men with mutation in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene despite increased HDL levels". J Clin Invest. 97 (12): 2917–23. doi:10.1172/JCI118751. PMID 8675707. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Sturek, JM.; Castle, JD.; Trace, AP.; Page, LC.; Castle, AM.; Evans-Molina, C.; Parks, JS.; Mirmira, RG.; Hedrick, CC. (2010). "An intracellular role for ABCG1-mediated cholesterol transport in the regulated secretory pathway of mouse pancreatic beta cells". J Clin Invest. 120 (7): 2575–89. doi:10.1172/JCI41280. PMID 20530872. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Rayner, KJ.; Suárez, Y.; Dávalos, A.; Parathath, S.; Fitzgerald, ML.; Tamehiro, N.; Fisher, EA.; Moore, KJ.; Fernández-Hernando, C. (2010). "MiR-33 contributes to the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis". Science. 328 (5985): 1570–3. doi:10.1126/science.1189862. PMID 20466885. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Marquart, TJ.; Allen, RM.; Ory, DS.; Baldán, A. (2010). "miR-33 links SREBP-2 induction to repression of sterol transporters". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (27): 12228–32. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005191107. PMID 20566875. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Najafi-Shoushtari, SH.; Kristo, F.; Li, Y.; Shioda, T.; Cohen, DE.; Gerszten, RE.; Näär, AM. (2010). "MicroRNA-33 and the SREBP host genes cooperate to control cholesterol homeostasis". Science. 328 (5985): 1566–9. doi:10.1126/science.1189123. PMID 20466882. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Wang, MD.; Franklin, V.; Sundaram, M.; Kiss, RS.; Ho, K.; Gallant, M.; Marcel, YL. (2007). "Differential regulation of ATP binding cassette protein A1 expression and ApoA-I lipidation by Niemann-Pick type C1 in murine hepatocytes and macrophages". J Biol Chem. 282 (31): 22525–33. doi:10.1074/jbc.M700326200. PMID 17553802. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ de Souza, JA.; Vindis, C.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Rye, KA.; Couturier, M.; Therond, P.; Chantepie, S.; Salvayre, R.; Chapman, MJ. (2010). "Small, dense HDL 3 particles attenuate apoptosis in endothelial cells: pivotal role of apolipoprotein A-I". J Cell Mol Med. 14 (3): 608–20. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00713.x. PMID 19243471. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Saddar S, Mineo C, Shaul PW (2010). "Signaling by the high-affinity HDL receptor scavenger receptor B type I." Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 30 (2): 144–50. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.196170. PMID 20089950.

- ↑ Radojkovic C, Genoux A, Pons V, Combes G, de Jonge H, Champagne E; et al. (2009). "Stimulation of cell surface F1-ATPase activity by apolipoprotein A-I inhibits endothelial cell apoptosis and promotes proliferation". Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 29 (7): 1125–30. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.187997. PMID 19372457.

- ↑ van Etten, RW.; de Koning, EJ.; Verhaar, MC.; Gaillard, CA.; Rabelink, TJ. (2002). "Impaired NO-dependent vasodilation in patients with Type II (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus is restored by acute administration of folate". Diabetologia. 45 (7): 1004–10. doi:10.1007/s00125-002-0862-1. PMID 12136399. Unknown parameter

|month=ignored (help)