Statin induced myopathy

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Rim Halaby

Overview

Definition

Statin induced myopathy is a spectrum of muscular problems caused by the intake of statins. Myopathy by definition is any pathology of the muscle. The spectrum of statin induced myopathy includes:

Myalgia

- Myalgia is defined as one or combination of symptoms of muscle weakness, tenderness or pain in the context of normal or minimally elevated creatinine kinase.

- Patients usually complain of cramping feeling in the muscles.

Asymptomatic Increase in Creatine Kinase

Myositis

- Myositis is the inflammation of the muscle.

- Myositis is defined as the presence of symptoms of muscle weakness, tenderness or pain in the setting of an elevated creatine kinase up to ten folds the normal level.

Rhabdomyolysis

- Rhabdomyolysis is the acute degeneration of the skeletal muscle.

- It is a potentially lethal condition due to its associated nephrotoxicity caused by myoglobinuria and myoglobinemia.

- Creatine kinase is elevated in rhabdomyolysis more than ten folds the upper normal limits.

- The complications of rhabdomyolysis are acute tubular necrosis, hypocalcemia, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, hyperuricemia, DIC and cardiomyopathy.[1]

Other Statin Induced Myopathies

- Elevated creatine kinase after statin withdrawal[2]

- Autoimmune myopathy requiring immunosuppressive therapy[3]

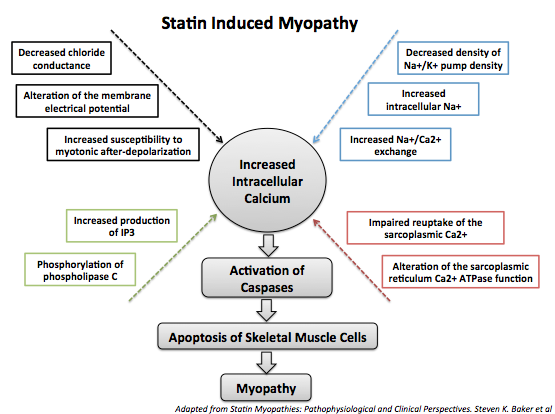

Pathophysiology

Statin induced myopathy has a complex poorly understood multifactorial pathophysiology. It is postulated that statin induced myopathy is caused by apoptosis of the skeletal muscle cells because of disrupted intracellular calcium signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction due to depletion of mevalonate metabolism products, notably isoprenoids.[4]

The following changes are caused by statin:

- Changes in cholesterol content and alteration of the membrane fluidity of skeletal muscle cells which disrupts their normal function

- Changes in skeletal muscle cells membrane electrical properties

- Changes in Na+/K+ pump density resulting in decreased production of ATP

- Changes in the excitation-contraction coupling

- Changes in the cell surface receptor transduction cascades

- Decreased synthesis of ubiquinone (Q10), a component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, leading to decreased ATP production and decreased free radical scavenging

- Increased intracellular calcium causing apoptosis of the skeletal muscle cells[1]

- Decreased mevalonate metabolism products, particularly isoprenoids, leading to a chain of events that culminate in the apoptosis of skeletal muscle cells[4]

In addition, muscle biopsies of patients suffering from statin induced rhabdomyolysis show a ragged red fibers appearance.[5]

- Shown below is an image depicting the mechanism of statin induced myopathy through increasing the intracellular calcium concentration.

Prevalence

The prevalence of statin induced myopathy, described as a spectrum of clinical conditions ranging from myalgia to myositis and rhabdomyolysis, is almost 10-15%[6]

Risk Factors

Intrinsic Risk Factors

- Advanced age (> 80 years)[7]

- Carnitine palmityl transferase II deficiency

- Diabetes mellitus

- Genetic polymorphisms of CYP450 isoenzymes (single nucleotide polymorphism of the gene SLCO1B1)[6]

- Hepatic disease

- Hypertension

- Hypothyroidism

- McArdle disease

- Metabolic muscle disease

- Myadenylate deaminase deficiency[8]

- Renal disease

- Small body mass index[7]

Extrinsic Risk Factors

- Alcohol consumption

- Amiodarone

- Azole antifungals

- Cyclosporins

- Fibrates particularly gemfibrozil (Cerivastatin in combination with gemfibrosil)[9]

- Grapefruit juice (> 1quart/day)

- Heavy exercise

- High dose of statin[6]

- Macrolide antibiotics

- Major trauma[9]

- Polypharmacy[6]

- Protease inhibitors[8]

- Surgery[9]

- Warfarin

Screening

- The American Heart Association and the National Heart, Lung, and. Blood Institute (AHA/NHLBI) statin clinical advisory panel recommends the measurement of the creatine kinase level before the initiation of statin therapy.

- The national lipid association does not recommend the measurement of the creatine kinase level before the initiation of statin therapy for all patients. It is useful to check the creatine level in patients with high risk factors for statin induced myopathy as for example patient with kidney diseases.[6]

Symptoms

The symptoms of statin induced myopathy belong to a spectrum ranging from being mild and asymptomatic to severe and lethal. The time of onset of symptoms varies among people, but the median of onset of symptoms is four weeks since the beginning of the treatment. Similarly, the time for the resolution of symptoms after appropriate management also varies among individuals.[10]

The list of symptoms is the following:

- Fatigue

- Generalized aching

- Low back or proximal muscle pain

- Myalgia

- Nocturnal muscle cramps

- Tendon pain

- Weakness[11]

Diagnosis

Initial Evaluation

A proper evaluation should be done by checking the following:

- The level of creatine kinase compared to the upper limit of normal (ULN)

- The list of medications the patient is taking

- [[CYP450[[ inhibitors: examples of CYP450 inhibitors are azole antifungals (itraconazole, ketoconazole, fluconazole), macrolide antibiotics (erythromycin, clarithromycin), protease inhibitors ( ritonavir, nelfinavir, indinavir).

- Fibrates: the combination of statin with fibrates is beneficial in the case of metabolic syndrome or diabetic dyslipidemia; however, fibrates increases the risk of statin induced myopathy.

- TSH level as hypothyroidism is a risk factor for statin induced myopathy.

- History of excessive exercise or trauma.[6]

Treatment

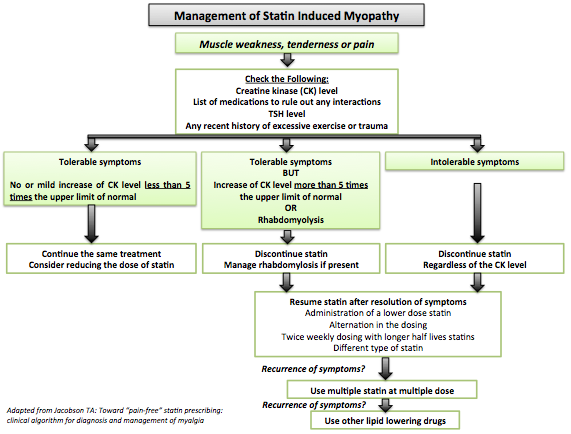

When symptoms of myopathy or elevation of creatine kinase occur in the setting of a patient taking statin, the majority of patients safely continue the treatment with statin. The decision on whether the patient can discontinue or continue statin depends on two factors:

- Severity of the symptoms

- Increase in the creatine kinase level

Tolerable Symptoms with Absent or Mild Elevation of Creatine Kinase<5ULN

- Continue statin[12]

- Consider lowering the dose of statin, adjust the optimal dose of statin depending on the symptoms of the patient

Tolerable Symptoms with Absent or Mild Elevation of Creatine Kinase>5ULN or with Rhabdomyolysis

- Discontinue statin

- Ensure an appropriate management for rhabdomyolysis if present by good hydration and follow up[6]

- Resume the treatment with statin once the symptoms are resolved. Modify the treatment regimen as follows:

- Monitor creatinine kinase levels.

Intolerable Symptoms

- Discontinue statin regardless of the level of the creatine kinase.[6]

- Resume the treatment with statin once the symptoms are resolved. Modify the treatment regimen as follows:

- Administration of a lower dose statin

- Alternation in the dosing

- Twice weekly dosing with longer half lives statins

- Different type of statin.[6]

- Monitor creatinine kinase levels.

Recurrence of Symptoms

If the symptoms recur despite appropriate management consider:

Multiple statin therapy at multiple doses

- Rosuvastatin: daily, low dose (2.5-5 mg/day) or alternate-day dose or weekly[13]

- Atorvastatin: either alternate-day dose (5-10 mg) or 10 mg twice weekly[14]

- Fluvastatin XL: 80 mg/day[15]

Other lipid lowering drugs[16]

Lifestyle changes including diet and exercise

- Shown below is an image summarizing the management plan for statin induced myopathy.[17]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Baker, S.K. & Tarnopolsky, M.A. (2001). Statin myopathies: pathophysiologic and clinical perspectives. Clin. Invest. Med., 24(5): 258-272.

- ↑ Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH (2003). "Statin-associated myopathy". JAMA. 289 (13): 1681–90. doi:10.1001/jama.289.13.1681. PMID 12672737.

- ↑ Radcliffe KA, Campbell WW (2008). "Statin myopathy". Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 8 (1): 66–72. PMID 18367041.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dirks AJ, Jones KM (2006). "Statin-induced apoptosis and skeletal myopathy". Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 291 (6): C1208–12. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00226.2006. PMID 16885396.

- ↑ Mohaupt MG, Karas RH, Babiychuk EB, et al.: Association between statin-associated myopathy and skeletal muscle damage. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J 2009, 181:E11–E18

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 Harper CR, Jacobson TA (2010). "Evidence-based management of statin myopathy". Curr Atheroscler Rep. 12 (5): 322–30. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0120-9. PMID 20628837.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Venero CV, Thompson PD (2009). "Managing statin myopathy". Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 38 (1): 121–36. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2008.11.002. PMID 19217515.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Toth PP, Harper CR, Jacobson TA: Clinical characterization and molecular mechanisms of statin myopathy. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2008, 6:955–969

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Hamilton-Craig I (2001). "Statin-associated myopathy". Med J Aust. 175 (9): 486–9. PMID 11758079.

- ↑ Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, et al.: Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyper- lipidemic patients–the PRIMO study [see comment]. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2005, 19:403–414.

- ↑ Toth PP, Harper CR, Jacobson TA: Clinical characterization and molecular mechanisms of statin myopathy. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2008, 6:955–969.

- ↑ Blaier O, Lishner M, Elis A (2011). "Managing statin-induced muscle toxicity in a lipid clinic". J Clin Pharm Ther. 36 (3): 336–41. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01254.x. PMID 21414023.

- ↑ Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Kakafika AI, et al.: Effectiveness of ezetimibe alone or in combination with twice a week Atorvastatin (10 mg) for statin intolerant high-risk patients. Am J Cardiol 2008, 101:483–485.

- ↑ Rivers SM, Kane MP, Busch RS, et al.: Colesevelam hydrochloride-ezetimibe combination lipid-lowering therapy in patients with diabetes or metabolic syndrome and a history of statin intolerance. Endocr Pract 2007, 13:11–16.

- ↑ Backes JM, Venero CV, Gibson CA, et al.: Effectiveness and tolerability of every-other-day rosuvastatin dosing in patients with prior statin intolerance. Ann Pharmacother 2008, 42:34–346.

- ↑ Lu Z, Kou W, Du B, et al.: Effect of Xuezhikang, an extract from red yeast Chinese rice, on coronary events in a Chinese population with previous myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2008, 101:1689–1693.

- ↑ Jacobson TA: Toward “pain-free” statin prescribing: clinical algorithm for diagnosis and management of myalgia [see comment]. Mayo Clin Proc 2008, 83:687–700.