Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Template:DiseaseDisorder infobox

| Human immunodeficiency virus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

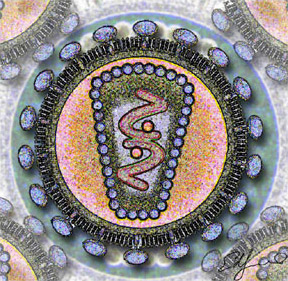

Stylized rendering of a cross section

of the human immunodeficiency virus | ||||||

| Virus classification | ||||||

| ||||||

| Species | ||||||

|

To read more about AIDS, click here.

To read about the difference between HIV & AIDS, click here.

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1] Template:HIV

Overview

Origin and discovery

- See AIDS origin

Classification

HIV is a member of the genus Lentivirus,[1] part of the family of Retroviridae.[2] Lentiviruses have many common morphologies and biological properties. Many species are infected by lentiviruses, which are characteristically responsible for long-duration illnesses with a long incubation period.[3] Lentiviruses are transmitted as single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA viruses. Upon entry of the target cell, the viral RNA genome is converted to double-stranded DNA by a virally encoded reverse transcriptase that is present in the virus particle. This viral DNA is then integrated into the cellular DNA by a virally encoded integrase so that the genome can be transcribed. Once the virus has infected the cell, two pathways are possible: either the virus becomes latent and the infected cell continues to function, or the virus becomes active and replicates, and a large number of virus particles are liberated that can then infect other cells.

Two species of HIV infect humans: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is thought to have originated in southern Cameroon after jumping from wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes troglodytes) to humans during the twentieth century.[4][5] HIV-1 is the virus that was initially discovered and termed LAV. It is more virulent and relatively easy transmitted and is the cause of the majority of HIV infections globally. HIV-2 may have originated from the Sooty Mangabey (Cercocebus atys), an Old World monkey of Guinea-Bissau, Gabon, and Cameroon.[6] HIV-2 is less transmittable than HIV-1 and is largely confined to West Africa.[6]

Early history

- See History of known cases and spread for early cases of HIV / AIDS

Transmission

Structure and genome

Tropism

The term viral tropism refers to which cell types HIV infects. HIV can infect a variety of immune cells such as CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and microglial cells. HIV-1 entry to macrophages and CD4+ T cells is mediated through interaction of the virion envelope glycoproteins (gp120) with the CD4 molecule on the target cells and also with chemokine coreceptors.[7]

Macrophage (M-tropic) strains of HIV-1, or non-syncitia-inducing strains (NSI) use the β-chemokine receptor CCR5 for entry and are thus able to replicate in macrophages and CD4+ T cells.[8] This CCR5 coreceptor is used by almost all primary HIV-1 isolates regardless of viral genetic subtype. Indeed, macrophages play a key role in several critical aspects of HIV infection. They appear to be the first cells infected by HIV and perhaps the source of HIV production when CD4+ cells become depleted in the patient. Macrophages and microglial cells are the cells infected by HIV in the central nervous system. In tonsils and adenoids of HIV-infected patients, macrophages fuse into multinucleated giant cells that produce huge amounts of virus.

T-tropic isolates, or syncitia-inducing (SI) strains replicate in primary CD4+ T cells as well as in macrophages and use the α-chemokine receptor, CXCR4, for entry.[8][9][10] Dual-tropic HIV-1 strains are thought to be transitional strains of the HIV-1 virus and thus are able to use both CCR5 and CXCR4 as co-receptors for viral entry.

The α-chemokine, SDF-1, a ligand for CXCR4, suppresses replication of T-tropic HIV-1 isolates. It does this by down-regulating the expression of CXCR4 on the surface of these cells. HIV that use only the CCR5 receptor are termed R5, those that only use CXCR4 are termed X4, and those that use both, X4R5. However, the use of coreceptor alone does not explain viral tropism, as not all R5 viruses are able to use CCR5 on macrophages for a productive infection[8] and HIV can also infect a subtype of myeloid dendritic cells,[11] which probably constitute a reservoir that maintains infection when CD4+ T cell numbers have declined to extremely low levels.

Some people are resistant to certain strains of HIV.[12] One example of how this occurs is people with the CCR5-Δ32 mutation; these people are resistant to infection with R5 virus as the mutation stops HIV from binding to this coreceptor, reducing its ability to infect target cells.

Sexual intercourse is the major mode of HIV transmission. Both X4 and R5 HIV are present in the seminal fluid which is passed from partner to partner. The virions can then infect numerous cellular targets and disseminate into the whole organism. However, a selection process leads to a predominant transmission of the R5 virus through this pathway.[13][14][15] How this selective process works is still under investigation, but one model is that spermatozoa may selectively carry R5 HIV as they possess both CCR3 and CCR5 but not CXCR4 on their surface[16] and that genital epithelial cells preferentially sequester X4 virus.[17] In patients infected with subtype B HIV-1, there is often a co-receptor switch in late-stage disease and T-tropic variants appear that can infect a variety of T cells through CXCR4.[18] These variants then replicate more aggressively with heightened virulence that causes rapid T cell depletion, immune system collapse, and opportunistic infections that mark the advent of AIDS.[19] Thus, during the course of infection, viral adaptation to the use of CXCR4 instead of CCR5 may be a key step in the progression to AIDS. A number of studies with subtype B-infected individuals have determined that between 40 and 50% of AIDS patients can harbour viruses of the SI, and presumably the X4, phenotype.[20][21]

Replication cycle

Genetic variability

The clinical course of infection

- For more details on this topic, see AIDS Diagnosis, AIDS Symptoms and Complications and WHO Disease Staging System for HIV Infection and Disease

Infection with HIV-1 is associated with a progressive decrease of the CD4+ T cell count and an increase in viral load. The stage of infection can be determined by measuring the patient's CD4+ T cell count, and the level of HIV in the blood.

The initial infection with HIV generally occurs after transfer of body fluids from an infected person to an uninfected one. The first stage of infection, the primary, or acute infection, is a period of rapid viral replication that immediately follows the individual's exposure to HIV leading to an abundance of virus in the peripheral blood with levels of HIV commonly approaching several million viruses per mL.[22] This response is accompanied by a marked drop in the numbers of circulating CD4+ T cells. This acute viremia is associated in virtually all patients with the activation of CD8+ T cells, which kill HIV-infected cells, and subsequently with antibody production, or seroconversion. The CD8+ T cell response is thought to be important in controlling virus levels, which peak and then decline, as the CD4+ T cell counts rebound to around 800 cells per mL (the normal value is 1200 cells per mL ). A good CD8+ T cell response has been linked to slower disease progression and a better prognosis, though it does not eliminate the virus.[23] During this period (usually 2-4 weeks post-exposure) most individuals (80 to 90%) develop an influenza or mononucleosis-like illness called acute HIV infection, the most common symptoms of which may include fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, rash, myalgia, malaise, mouth and esophagal sores, and may also include, but less commonly, headache, nausea and vomiting, enlarged liver/spleen, weight loss, thrush, and neurological symptoms. Infected individuals may experience all, some, or none of these symptoms. The duration of symptoms varies, averaging 28 days and usually lasting at least a week.[24] Because of the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, they are often not recognized as signs of HIV infection. Even if patients go to their doctors or a hospital, they will often be misdiagnosed as having one of the more common infectious diseases with the same symptoms. Consequently, these primary symptoms are not used to diagnose HIV infection as they do not develop in all cases and because many are caused by other more common diseases. However, recognizing the syndrome can be important because the patient is much more infectious during this period. [25]

| sensitivity | specificity | |

|---|---|---|

| Fever | 88% | 50% |

| Malaise | 73% | 58% |

| Myalgia | 60% | 74% |

| Rash | 58% | 79% |

| Headache | 55% | 56% |

| Night sweats | 50% | 68% |

| Sore throat | 43% | 51% |

| Lymphadenopathy | 38% | 71% |

| Arthralgia | 28% | 87% |

| Nasal congestion | 18% | 62% |

A strong immune defense reduces the number of viral particles in the blood stream, marking the start of the infection's clinical latency stage. Clinical latency can vary between two weeks and 20 years. During this early phase of infection, HIV is active within lymphoid organs, where large amounts of virus become trapped in the follicular dendritic cells (FDC) network.[26] The surrounding tissues that are rich in CD4+ T cells may also become infected, and viral particles accumulate both in infected cells and as free virus. Individuals who are in this phase are still infectious. During this time, CD4+ CD45RO+ T cells carry most of the proviral load.[27]

When CD4+ T cell numbers decline below a critical level, cell-mediated immunity is lost, and infections with a variety of opportunistic microbes appear. The first symptoms often include moderate and unexplained weight loss, recurring respiratory tract infections (such as sinusitis, bronchitis, otitis media, pharyngitis), prostatitis, skin rashes, and oral ulcerations. Common opportunistic infections and tumors, most of which are normally controlled by robust CD4+ T cell-mediated immunity then start to affect the patient. Typically, resistance is lost early on to oral Candida species and to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which leads to an increased susceptibility to oral candidiasis (thrush) and tuberculosis. Later, reactivation of latent herpes viruses may cause worsening recurrences of herpes simplex eruptions, shingles, Epstein-Barr virus-induced B-cell lymphomas, or Kaposi's sarcoma, a tumor of endothelial cells that occurs when HIV proteins such as Tat interact with Human Herpesvirus-8. Pneumonia caused by the fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii is common and often fatal. In the final stages of AIDS, infection with cytomegalovirus (another herpes virus) or Mycobacterium avium complex is more prominent. Not all patients with AIDS get all these infections or tumors, and there are other tumors and infections that are less prominent but still significant.

HIV test

Treatment

- See also AIDS Treatment and Antiretroviral drug.

There is currently no vaccine or cure for HIV or AIDS. The only known method of prevention is avoiding exposure to the virus. However, an antiretroviral treatment, known as post-exposure prophylaxis, is believed to reduce the risk of infection if begun directly after exposure.[28] Current treatment for HIV infection consists of highly active antiretroviral therapy, or HAART.[29] This has been highly beneficial to many HIV-infected individuals since its introduction in 1996, when the protease inhibitor-based HAART initially became available.[30] Current HAART options are combinations (or "cocktails") consisting of at least three drugs belonging to at least two types, or "classes," of anti-retroviral agents. Typically, these classes are two nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NARTIs or NRTIs) plus either a protease inhibitor or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). Because AIDS progression in children is more rapid and less predictable than in adults, particularly in young infants, more aggressive treatment is recommended for children than adults.[31] In developed countries where HAART is available, doctors assess their patients thoroughly: measuring the viral load, how fast CD4 declines, and patient readiness. They then decide when to recommend starting treatment.[32]

HAART allows the stabilisation of the patient’s symptoms and viremia, but it neither cures the patient, nor alleviates the symptoms; high levels of HIV-1, often HAART resistant, return once treatment is stopped.[33][34] Moreover, it would take more than a lifetime for HIV infection to be cleared using HAART.[35] Despite this, many HIV-infected individuals have experienced remarkable improvements in their general health and quality of life, which has led to a large reduction in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality in the developed world.[30][36][37] A computer based study in 2006 projected that following the 2004 United States treatment guidelines gave an average life expectancy of an HIV infected individual to be 32.1 years from the time of infection if treatment was started when the CD4 count was 350/µL.[38] This study was limited as it did not take into account possible future treatments and the projection has not been confirmed within a clinical cohort setting. In the absence of HAART, progression from HIV infection to AIDS has been observed to occur at a median of between nine to ten years and the median survival time after developing AIDS is only 9.2 months.[39] However, HAART sometimes achieves far less than optimal results, in some circumstances being effective in less than fifty percent of patients. This is due to a variety of reasons such as medication intolerance/side effects, prior ineffective antiretroviral therapy and infection with a drug-resistant strain of HIV. However, non-adherence and non-persistence with antiretroviral therapy is the major reason most individuals fail to benefit from HAART.[40] The reasons for non-adherence and non-persistence with HAART are varied and overlapping. Major psychosocial issues, such as poor access to medical care, inadequate social supports, psychiatric disease and drug abuse contribute to non-adherence. The complexity of these HAART regimens, whether due to pill number, dosing frequency, meal restrictions or other issues along with side effects that create intentional non-adherence also contribute to this problem.[41][42][43] The side effects include lipodystrophy, dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, an increase in cardiovascular risks and birth defects.[44][45]

The timing for starting HIV treatment is still debated. There is no question that treatment should be started before the patient's CD4 count falls below 200, and most national guidelines say to start treatment once the CD4 count falls below 350; but there is some evidence from cohort studies that treatment should be started before the CD4 count falls below 350.[46][36] There is also evidence to say that treatment should be started before CD4 percentage falls below 15%.[47] In those countries where CD4 counts are not available, patients with WHO stage III or IV disease[48] should be offered treatment.

Anti-retroviral drugs are expensive, and the majority of the world's infected individuals do not have access to medications and treatments for HIV and AIDS.[49] Research to improve current treatments includes decreasing side effects of current drugs, further simplifying drug regimens to improve adherence, and determining the best sequence of regimens to manage drug resistance. Unfortunately, only a vaccine is thought to be able to halt the pandemic. This is because a vaccine would cost less, thus being affordable for developing countries, and would not require daily treatment.[49] However, after over 20 years of research, HIV-1 remains a difficult target for a vaccine.[49] In February 2007, The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases published a report that gave details of a region on HIV's surface that is a potential target for a vaccine.[50]

Researchers at the Heinrich Pette Institute of Experimental Virology and Immunology at Hamburg have engineered an enzyme called Cre recombinase which is able to remove HIV from an infected cell.[51] Similarly, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden have engineered an enzyme called Tre recombinase which is able to remove HIV from an infected cell.[52] These enzymes promise a treatment in which a patient's stem cells are extracted, cured, and reinjected to promulgate the enzyme into the body. The carried enzyme then finds and removes the virus.

Epidemiology

AIDS denialism

A small minority of scientists and activists question the connection between HIV and AIDS,[53] the existence of HIV itself,[54] or the validity of current testing and treatment methods. These claims have been examined and widely rejected by the scientific community,[55] although they have had a political impact, particularly in South Africa, where governmental acceptance of AIDS denialism has been blamed for an ineffective response to that country's AIDS epidemic.[56][57][58]

Related Chapters

- AIDS

- HIV disease

- Hepatitis C with HIV coinfection

- Hepatitis B with HIV coinfection

- Tuberculosis and HIV coinfection

- HIV and tuberculosis coinfection : drug interaction

References

- ↑ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. "61.0.6. Lentivirus". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2006-02-28. Unknown parameter

|publishyear=ignored (help) - ↑ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. "61. Retroviridae". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2006-02-28. Unknown parameter

|publishyear=ignored (help) - ↑ Lévy, J. A. (1993). "HIV pathogenesis and long-term survival". AIDS. 7 (11): 1401–1410. PMID 8280406.

- ↑ Gao, F., Bailes, E., Robertson, D. L., Chen, Y., Rodenburg, C. M., Michael, S. F., Cummins, L. B., Arthur, L. O., Peeters, M., Shaw, G. M., Sharp, P. M., and Hahn, B. H. (1999). "Origin of HIV-1 in the Chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes". Nature. 397 (6718): 436–441. doi:10.1038/17130. PMID 9989410.

- ↑ Keele, B. F., van Heuverswyn, F., Li, Y. Y., Bailes, E., Takehisa, J., Santiago, M. L., Bibollet-Ruche, F., Chen, Y., Wain, L. V., Liegois, F., Loul, S., Mpoudi Ngole, E., Bienvenue, Y., Delaporte, E., Brookfield, J. F. Y., Sharp, P. M., Shaw, G. M., Peeters, M., and Hahn, B. H. (2006). "Chimpanzee Reservoirs of Pandemic and Nonpandemic HIV-1". Science. Online 2006-05-25. doi:10.1126/science.1126531.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Reeves, J. D. and Doms, R. W (2002). "Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 2". J. Gen. Virol. 83 (Pt 6): 1253–1265. PMID 12029140.

- ↑ Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChan - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Coakley, E., Petropoulos, C. J. and Whitcomb, J. M. (2005). "Assessing ch vbgemokine co-receptor usage in HIV". Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18 (1): 9–15. PMID 15647694.

- ↑ Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton RE, Hill CM, Davis CB, Peiper SC, Schall TJ, Littman DR, Landau NR. (1996). "Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1". Nature. 381 (6584): 661–666. doi:10.1038/381661a0. PMID 8649511.

- ↑ Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Berger EA. (1996). "HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor". Science. 272 (5263): 872–877. doi:10.1126/science.272.5263.872. PMID 8629022.

- ↑ Knight, S. C., Macatonia, S. E. and Patterson, S. (1990). "HIV I infection of dendritic cells". Int. Rev. Immunol. 6 (2–3): 163–175. PMID 2152500.

- ↑ Tang, J. and Kaslow, R. A. (2003). "The impact of host genetics on HIV infection and disease progression in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy". AIDS. 17 (Suppl 4): S51–S60. PMID 15080180.

- ↑ Zhu T, Mo H, Wang N, Nam DS, Cao Y, Koup RA, Ho DD. (1993). "Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 patients with primary infection". Science. 261 (5125): 1179–1181. doi:10.1126/science.8356453. PMID 8356453.

- ↑ van’t Wout AB, Kootstra NA, Mulder-Kampinga GA, Albrecht-van Lent N, Scherpbier HJ, Veenstra J, Boer K, Coutinho RA, Miedema F, Schuitemaker H. (1994). "Macrophage-tropic variants initiate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection after sexual, parenteral, and vertical transmission". J Clin Invest. 94 (5): 2060–2067. PMID 7962552.

- ↑ Zhu T, Wang N, Carr A, Nam DS, Moor-Jankowski R, Cooper DA, Ho DD. (1996). "Genetic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in blood and genital secretions: evidence for viral compartmentalization and selection during sexual transmission". J Virol. 70 (5): 3098–3107. PMID 8627789.

- ↑ Muciaccia B, Padula F, Vicini E, Gandini L, Lenzi A, Stefanini M. (2005). "Beta-chemokine receptors 5 and 3 are expressed on the head region of human spermatozoon". FASEB J. 19 (14): 2048–2050. PMID 16174786.

- ↑ Berlier W, Bourlet T, Lawrence P, Hamzeh H, Lambert C, Genin C, Verrier B, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Pozzetto B, Delezay O. (2005). "Selective sequestration of X4 isolates by human genital epithelial cells: Implication for virus tropism selection process during sexual transmission of HIV". J Med Virol. 77 (4): 465–474. PMID 16254974.

- ↑ Clevestig P, Maljkovic I, Casper C, Carlenor E, Lindgren S, Naver L, Bohlin AB, Fenyo EM, Leitner T, Ehrnst A. (2005). "The X4 phenotype of HIV type 1 evolves from R5 in two children of mothers, carrying X4, and is not linked to transmission". AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 5 (21): 371–378. PMID 15929699.

- ↑ Moore JP. (1997). "Coreceptors: implications for HIV pathogenesis and therapy". Science. 276 (5309): 51–52. doi:10.1126/science.276.5309.51. PMID 9122710.

- ↑ Karlsson A, Parsmyr K, Aperia K, Sandstrom E, Fenyo EM, Albert J. (1994). "MT-2 cell tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates as a marker for response to treatment and development of drug resistance". J Infect Dis. 170 (6): 1367–1375. PMID 7995974.

- ↑ Koot M, van 't Wout AB, Kootstra NA, de Goede RE, Tersmette M, Schuitemaker H. (1996). "Relation between changes in cellular load, evolution of viral phenotype, and the clonal composition of virus populations in the course of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection". J Infect Dis. 173 (2): 349–354. PMID 8568295.

- ↑ Piatak, M., Jr, Saag, M. S., Yang, L. C., Clark, S. J., Kappes, J. C., Luk, K. C., Hahn, B. H., Shaw, G. M. and Lifson, J.D. (1993). "High levels of HIV-1 in plasma during all stages of infection determined by competitive PCR". Science. 259 (5102): 1749–1754. doi:10.1126/science.8096089. PMID 8096089.

- ↑ Pantaleo G, Demarest JF, Schacker T, Vaccarezza M, Cohen OJ, Daucher M, Graziosi C, Schnittman SS, Quinn TC, Shaw GM, Perrin L, Tambussi G, Lazzarin A, Sekaly RP, Soudeyns H, Corey L, Fauci AS. (1997). "The qualitative nature of the primary immune response to HIV infection is a prognosticator of disease progression independent of the initial level of plasma viremia". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 94 (1): 254–258. PMID 8990195.

- ↑ Kahn, J. O. and Walker, B. D. (1998). "Acute Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 infection". N. Engl. J. Med. 331 (1): 33–39. PMID 9647878.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Daar ES, Little S, Pitt J; et al. (2001). "Diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection. Los Angeles County Primary HIV Infection Recruitment Network". Ann. Intern. Med. 134 (1): 25–9. PMID 11187417.

- ↑ Burton GF, Keele BF, Estes JD, Thacker TC, Gartner S. (2002). "Follicular dendritic cell contributions to HIV pathogenesis". Semin Immunol. 14 (4): 275–284. PMID 12163303.

- ↑ Clapham PR, McKnight A. (2001). "HIV-1 receptors and cell tropism". Br Med Bull. 58 (4): 43–59. PMID 11714623.

- ↑ Fan, H., Conner, R. F. and Villarreal, L. P. eds, ed. (2005). AIDS : science and society (4th edition ed.). Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 0-7637-0086-X.

- ↑ Department of Health and Human Services (January, 2005). "A Pocket Guide to Adult HIV/AIDS Treatment January 2005 edition". Retrieved 2006-01-17. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - ↑ 30.0 30.1 Palella, F. J., Delaney, K. M., Moorman, A. C., Loveless, M. O., Fuhrer, J., Satten, G. A., Aschman, D. J. and Holmberg, S. D. (1998). "Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection". N. Engl. J. Med. 338 (13): 853–860. PMID 9516219.

- ↑ Department of Health and Human Services Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children (November 3, 2005). "Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-01-17. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - ↑ Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV Infection (October 6, 2005). "Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-01-17. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - ↑ Martinez-Picado, J., DePasquale, M. P., Kartsonis, N., Hanna, G. J., Wong, J., Finzi, D., Rosenberg, E., Gunthard, H. F., Sutton, L., Savara, A., Petropoulos, C. J., Hellmann, N., Walker, B. D., Richman, D. D., Siliciano, R. and D'Aquila, R. T. (2000). "Antiretroviral resistance during successful therapy of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 (20): 10948–10953. PMID 11005867.

- ↑ Dybul, M., Fauci, A. S., Bartlett, J. G., Kaplan, J. E., Pau, A. K.; Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV. (2002). "Guidelines for using antiretroviral agents among HIV-infected adults and adolescents". Ann. Intern. Med. 137 (5 Pt 2): 381–433. PMID 12617573.

- ↑ Blankson, J. N., Persaud, D., Siliciano, R. F. (2002). "The challenge of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 infection". Annu. Rev. Med. 53: 557–593. PMID 11818490.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Wood, E., Hogg, R. S., Yip, B., Harrigan, P. R., O'Shaughnessy, M. V. and Montaner, J. S. (2003). "Is there a baseline CD4 cell count that precludes a survival response to modern antiretroviral therapy?". AIDS. 17 (5): 711–720. PMID 12646794.

- ↑ Chene, G., Sterne, J. A., May, M., Costagliola, D., Ledergerber, B., Phillips, A. N., Dabis, F., Lundgren, J., D'Arminio Monforte, A., de Wolf, F., Hogg, R., Reiss, P., Justice, A., Leport, C., Staszewski, S., Gill, J., Fatkenheuer, G., Egger, M. E. and the Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. (2003). "Prognostic importance of initial response in HIV-1 infected patients starting potent antiretroviral therapy: analysis of prospective studies". Lancet. 362 (9385): 679–686. PMID 12957089.

- ↑ Schackman BR, Gebo KA, Walensky RP, Losina E, Muccio T, Sax PE, Weinstein MC, Seage GR 3rd, Moore RD, Freedberg KA. (2006). "The lifetime cost of current HIV care in the United States". Med Care. 44 (11): 990–997. PMID 17063130.

- ↑ Morgan, D., Mahe, C., Mayanja, B., Okongo, J. M., Lubega, R. and Whitworth, J. A. (2002). "HIV-1 infection in rural Africa: is there a difference in median time to AIDS and survival compared with that in industrialized countries?". AIDS. 16 (4): 597–632. PMID 11873003.

- ↑ Becker SL, Dezii CM, Burtcel B, Kawabata H, Hodder S. (2002). "Young HIV-infected adults are at greater risk for medication nonadherence". MedGenMed. 4 (3): 21. PMID 12466764.

- ↑ Nieuwkerk, P., Sprangers, M., Burger, D., Hoetelmans, R. M., Hugen, P. W., Danner, S. A., van Der Ende, M. E., Schneider, M. M., Schrey, G., Meenhorst, P. L., Sprenger, H. G., Kauffmann, R. H., Jambroes, M., Chesney, M. A., de Wolf, F., Lange, J. M. and the ATHENA Project. (2001). "Limited Patient Adherence to Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV-1 Infection in an Observational Cohort Study". Arch. Intern. Med. 161 (16): 1962–1968. PMID 11525698.

- ↑ Kleeberger, C., Phair, J., Strathdee, S., Detels, R., Kingsley, L. and Jacobson, L. P. (2001). "Determinants of Heterogeneous Adherence to HIV-Antiretroviral Therapies in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 26 (1): 82–92. PMID 11176272.

- ↑ Heath, K. V., Singer, J., O'Shaughnessy, M. V., Montaner, J. S. and Hogg, R. S. (2002). "Intentional Nonadherence Due to Adverse Symptoms Associated With Antiretroviral Therapy". J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 31 (2): 211–217. PMID 12394800.

- ↑ Montessori, V., Press, N., Harris, M., Akagi, L., Montaner, J. S. (2004). "Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection". CMAJ. 170 (2): 229–238. PMID 14734438.

- ↑ Saitoh, A., Hull, A. D., Franklin, P. and Spector, S. A. (2005). "Myelomeningocele in an infant with intrauterine exposure to efavirenz". J. Perinatol. 25 (8): 555–556. PMID 16047034.

- ↑ Wang C, Vlahov D, Galai N; et al. (2004). "Mortality in HIV-seropositive versus seronegative persons in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy". J. Infect. Dis. 190: 1046&ndash, 54. PMID 15319852.

- ↑ Moore, D.M.; Hogg, R.S.; Yip, B.; et al. (2006). "CD4 percentage is an independent predictor of survival in patients starting antiretroviral therapy with absolute CD4 cell counts between 200 and 350 cells/μL". HIV Med. 7: 383&ndash, 8. PMID 16903983.

- ↑ World Health Organisation (2006). "WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Ferrantelli F, Cafaro A, Ensoli B. (2004). "Nonstructural HIV proteins as targets for prophylactic or therapeutic vaccines". Curr Opin Biotechnol. 15 (6): 543–556. PMID 15560981.

- ↑ BBC News (2007). "Scientists expose HIV weak spot". Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ↑ Paternity Testing Labs (2007). "German scientists "cure" HIV-infected human lymphocytes". Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ↑ Terra Daily (2007). "Another Potential Cure For HIV Discovered". Retrieved 2007-06-29.

- ↑ Duesberg, P. H. (1988). "HIV is not the cause of AIDS". Science. 241 (4865): 514, 517. doi:10.1126/science.3399880. PMID 3399880.

- ↑ Papadopulos-Eleopulos, E., Turner, V. F., Papadimitriou, J., Page, B., Causer, D., Alfonso, H., Mhlongo, S., Miller, T., Maniotis, A. and Fiala, C. (2004). "A critique of the Montagnier evidence for the HIV/AIDS hypothesis". Med Hypotheses. 63 (4): 597&ndash, 601. PMID 15325002.

- ↑ For evidence of the scientific consensus that HIV is the cause of AIDS, see (for example):

- "The Durban Declaration". Nature. 406 (6791): 15–6. 2000. doi:10.1038/35017662. PMID 10894520. - full text here.

- Cohen, J. (1994). "The Controversy over HIV and AIDS" (PDF). Science. 266 (5191): 1642&ndash, 1649.

- Various. "Focus on the HIV-AIDS Connection: Resource links". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

- O'Brien SJ, Goedert JJ (1996). "HIV causes AIDS: Koch's postulates fulfilled". Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8 (5): 613–8. PMID 8902385.

- Galéa P, Chermann JC (1998). "HIV as the cause of AIDS and associated diseases". Genetica. 104 (2): 133–42. PMID 10220906.

- ↑ Watson J (2006). "Scientists, activists sue South Africa's AIDS 'denialists'". Nat. Med. 12 (1): 6. doi:10.1038/nm0106-6a. PMID 16397537.

- ↑ Baleta A (2003). "S Africa's AIDS activists accuse government of murder". Lancet. 361 (9363): 1105. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12909-1. PMID 12672319.

- ↑ Cohen J (2000). "South Africa's new enemy". Science. 288 (5474): 2168–70. doi:10.1126/science.288.5474.2168. PMID 10896606.

External links

- UNAIDS - Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS webpage

- PlusNews, The United Nations HIV and AIDS news service

- History of AIDS research at the NIH

- Medecins Sans Frontieres/Doctors Without Borders HIV/AIDS Pages

- AIDSinfo - HIV/AIDS Information - Comprehensive resource for HIV/AIDS treatment and clinical trial information from the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services

- HIV InSite - University of California San Francisco

- AIDS.ORG: Educating - Raising HIV Awareness - Building Community

- AIDSPortal - Latest policy, research, guidelines and case studies

- AIDS.gov Portal for all Federal domestic HIV/AIDS information and resources

- News media

- "The Age of Aids" March 30, 2006 Frontline

- Everything you wanted to know about HIV and AIDS — Provided by New Scientist.

- "The Graying of AIDS" - Older Americans living with HIV face unique challenges - TIME magazine, 08/14/06

- "Elite" HIV patients mystify doctors - Aug 16, 2006 | Reuters on Topix.net

- Online textbooks

- HIV Medicine 2006, medical textbook, 14th edition, 825 pages (free download)

- "The Molecules of HIV" information resource

- Advocacy

- Be the Generation - Information on HIV Vaccine Clinical Research in 20 American Cities

- Media Campaign: HIV leads to AIDS

- FightAIDS@Home

- HIV-AIDS-Counseling-Online.com

- Articles

- The Mechanism of HIV-1 Core Assembly: Insights from Three-Dimensional Reconstructions of Authentic Virions

- Unsafe Health Care and the HIV/AIDS Pandemic 2003

- The role of dendritic cells in HIV pathogenesis

- The HIV databases, Los Alamos National Laboratory

- Multimedia/video

- HIV DERMATOLOGY

- How Aids Works (with animation)

- Watch an animated tutorial on the life cycle of HIV

- Video of Treatment Update 2006 from the Conference on Retrovirus'

- Other sites

- HIV/AIDS at About.com provides a comprehensive collection of HIV and AIDS information, articles, statistics, and forums.

- POZ provides information and networking opportunities for the HIV community.

- AIDSmeds is a place to find complete and easy-to-read information on treating HIV & AIDS.

- AEGiS.org: AIDS Education Global Information System- Patient/clinician information & Historical news and treatment database

- AIDS Community Research Initiative of America - Community-based research and education for people living with HIV

- Data about people living with HIV/AIDS in the world (regional totals and percentage of adults with AIDS that are women)- from Data360

- Resources for HIV/AIDS and Sexual and Reproductive Health Integration Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for Communication Programs

- Pages with reference errors

- Pages with citations using unsupported parameters

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al.

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: editors list

- CS1 maint: Extra text: editors list

- CS1 maint: Extra text

- CS1 errors: dates

- HIV/AIDS

- Retroviruses

- Sexually transmitted diseases

- Immunodeficiency

- Acronyms