Cerebral aneurysm: Difference between revisions

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

** [[Aortic coarctation]] | ** [[Aortic coarctation]] | ||

** [[Hypertension]] | ** [[Hypertension]] | ||

==Diagnosis== | ==Diagnosis== | ||

===History and Symptoms=== | ===History and Symptoms=== | ||

Revision as of 17:35, 29 January 2013

For patient information, click here

| Cerebral aneurysm | |

| |

|---|---|

| Brain: Berry Aneurysm: Gross, natural color, close-up, an excellent view of typical berry aneurysm located on anterior cerebral artery Image courtesy of Professor Peter Anderson DVM PhD and published with permission © PEIR, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Department of Pathology |

|

Cerebral aneurysm Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Cerebral aneurysm On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Cerebral aneurysm |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Cafer Zorkun, M.D., Ph.D. [2]; Kalsang Dolma, M.B.B.S.[3]

Synonyms and keywords: Berry aneurysm

Causes

Aneurysms may result from

- congenital defects

- Preexisting conditions such as

- High blood pressure

- Atherosclerosis

- [[head (anatomy)|Head]trauma.

The pursuit to identify Genetics of Intracranial Aneurysms has identified a number of locations, most recently 1p34-36, 2p14-15, 7q11, 11q25, and 19q13.1-13.3.

Epidemiology and demographics

- About 5% of the population has some type of aneurysm in the brain, but only a small number of these aneurysms cause symptoms or rupture.

- Cerebral aneurysms occur more commonly in adults than in children but they may occur at any age.

- They are slightly more common in women than in men.

Risk Factors

Following are risk factors for cerebral aneurysms:

- Family history of cerebral aneurysms

- Certain medical problems such as

Diagnosis

History and Symptoms

- A person may have an aneurysm without having any symptoms.

- Symptoms depend on the location of the aneurysm, whether it breaks open, and what part of the brain it is pushing on, but may include:

- Double vision

- Loss of vision

- Headaches

- Eye pain

- Neck pain

- Stiff neck

- Symptoms of an aneurysm rupture may include:

- Confusion, lethargy, sleepiness, or stupor

- Eyelid drooping

- Headaches with nausea or vomiting

- Muscle weakness or difficulty moving any part of the body

- Numbness or decreased sensation in any part of the body

- Seizures

- Speech impairment

- Stiff neck (occasionally)

- Vision changes (double vision, loss of vision)

Physical Examination

General

Confusion, lethargy or stupor may be present.

Neurologic Examination

- Motor weakness may be present.

- Sensory abnormalities may be present.

- Neck stiffness may be present.

In outlining symptoms of ruptured cerebral aneurysm, it is useful to make use of the Hunt and Hess scale of subarachnoid hemorrhage severity:

- Grade 1: Asymptomatic; or minimal headache and slight nuchal rigidity. Approximate survival rate 70%.

- Grade 2: Moderate to severe headache; nuchal rigidity; no neurologic deficit except cranial nerve palsy. 60%.

- Grade 3: Drowsy; minimal neurologic deficit. 50%.

- Grade 4: Stuporous; moderate to severe hemiparesis; possibly early decerebrate rigidity and vegetative disturbances. 20%.

- Grade 5: Deep coma; decerebrate rigidity; moribund. 10%.

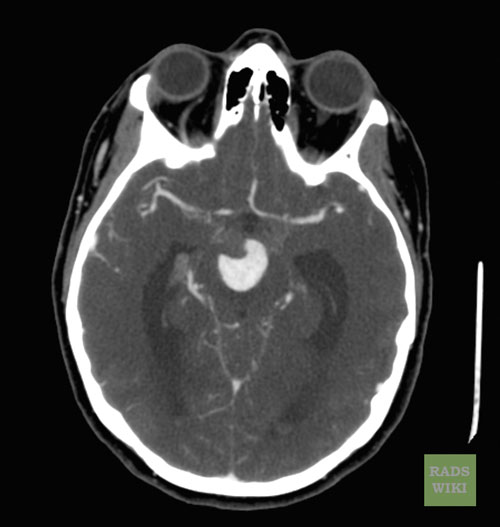

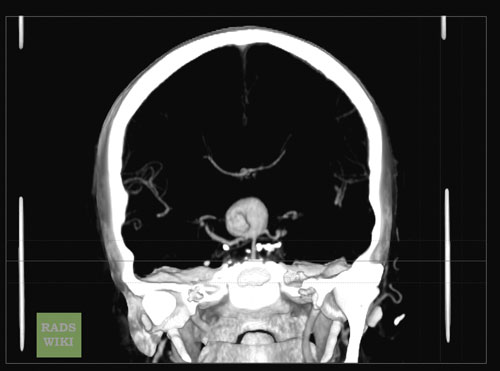

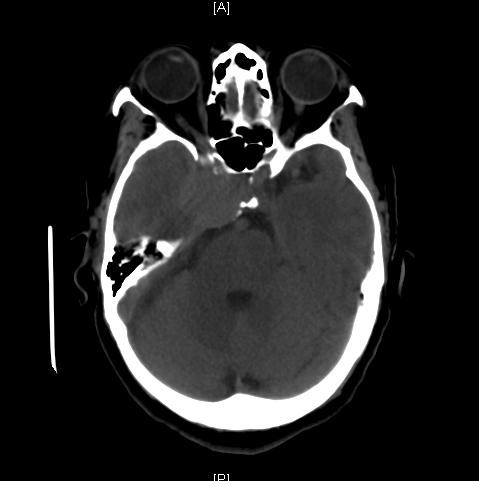

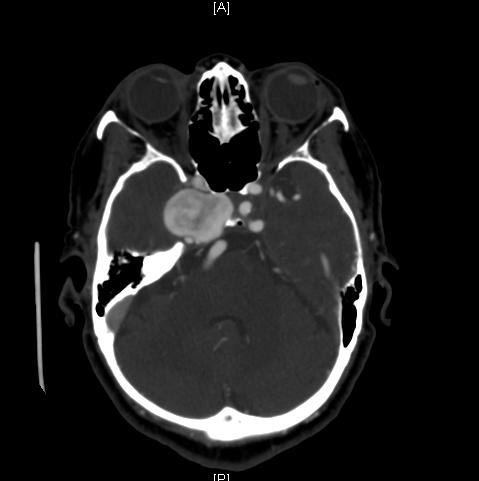

Multi Sliced CT

The Fisher Grade classifies the appearance of subarachnoid hemorrhage on CT scan:

- Grade 1: No hemorrhage evident.

- Grade 2: Subarachnoid hemorrhage less than 1mm thick.

- Grade 3: Subarachnoid hemorrhage more than 1mm thick.

- Grade 4: Subarachnoid hemorrhage of any thickness with intra-ventricular hemorrhage (IVH) or parenchymal extension.

The Fisher Grade is most useful in communicating the description of SAH. It is less useful prognostically than the Hunt-Hess scale.

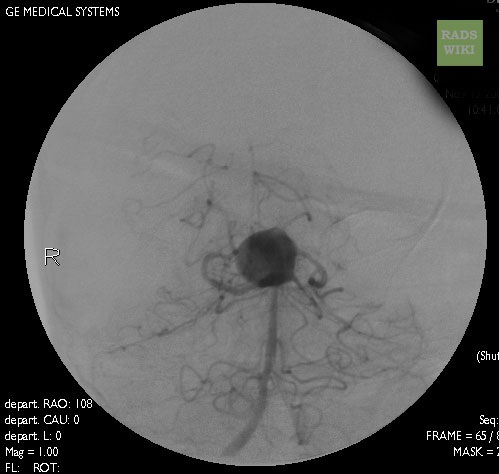

Images shown below are courtesy of RadsWiki and copylefted.

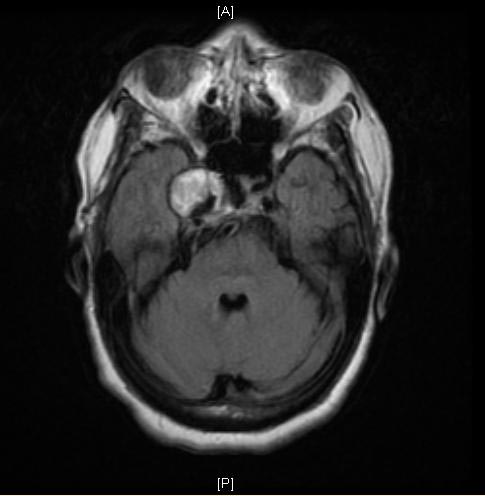

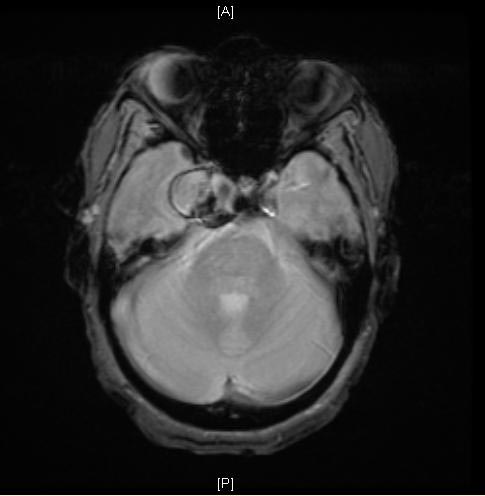

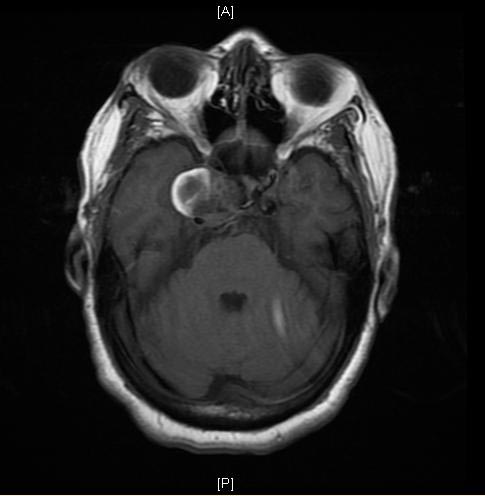

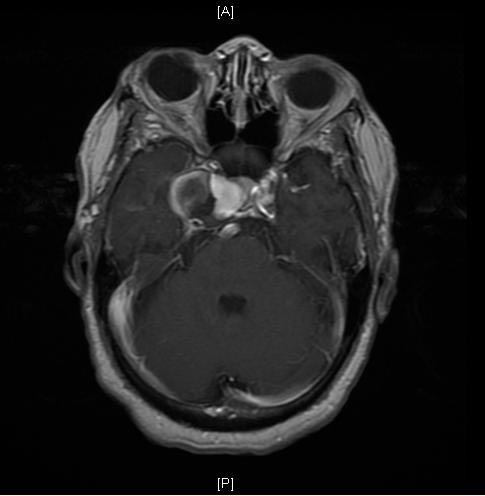

MRI

Images shown below are courtesy of RadsWiki and copylefted.

-

MRI: A large cavernous sinus aneurysm

-

MRI: A large cavernous sinus aneurysm

-

MRI: A large cavernous sinus aneurysm

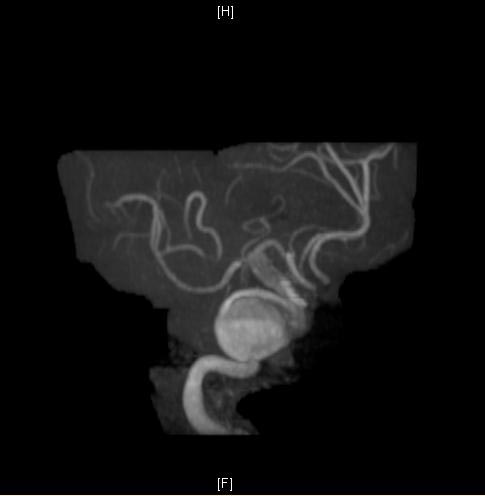

Angiography

Images shown below are courtesy of RadsWiki and copylefted.

-

Cranial Angiography: Same case as in MSCT images. A large basilar artery aneurysm

-

Cranial Angiography: Same case as in MSCT images. A large basilar artery aneurysm

Treatment

Emergency treatment for individuals with a ruptured cerebral aneurysm generally includes restoring deteriorating respiration and reducing intracranial pressure. Currently there are two treatment options for brain aneurysms. Either surgical clipping or endovascular coiling is usually performed within the first three days to occlude the ruptured aneurysm and reduce the risk of rebleeding.

Surgical clipping: Surgical clipping was introduced by Walter Dandy of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1937. It consists of performing a craniotomy, exposing the aneurysm, and closing the base of the aneurysm with a clip. The surgical technique has been modified and improved over the years. Surgical clipping has a lower rate of aneurysm recurrence after treatment. Either surgical clipping or endovascular coiling is usually performed within the first three days to occlude the ruptured aneurysm and reduce the risk of rebleeding.

Endovascular coiling: This was introduced by Guido Guglielmi at UCLA in 1991. It consists of passing a catheter into the femoral artery in the groin, through the aorta, into the brain arteries, and finally into the aneurysm itself. Once the catheter is in the aneurysm, platinum coils are pushed into the aneurysm and released. These coils initiate a clotting or thrombotic reaction within the aneurysm that, if successful, will eliminate the aneurysm. In the case of broad-based aneurysms, a stent is passed first into the parent artery to serve as a scaffold for the coils ("stent-assisted coiling").Either surgical clipping or endovascular coiling is usually performed within the first three days to occlude the ruptured aneurysm and reduce the risk of rebleeding.

At this point it appears that the risks associated with surgical clipping and endovascular coiling, in terms of stroke or death from the procedure, are the same. The major problem associated with endovascular coiling, however, is a higher aneurysm recurrence rate. For instance, the most recent study by Jacques Moret and colleagues from Paris, France, (a group with one of the largest experiences in endovascular coiling) indicates that 28.6% of aneurysms recurred within one year of coiling, and that the recurrence rate increased with time. [1] These results are similar to those previously reported by other endovascular groups. For instance Jean Raymond and colleagues from Montreal, Canada, (another group with a large experience in endovascular coiling) reported that 33.6% of aneurysms recurred within one year of coiling. [2] The long-term coiling results of one of the two prospective, randomized studies comparing surgical clipping versus endovascular coiling, namely the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) are turning out to be similarly worrisome. In ISAT, the need for late retreatment of aneurysms was 6.9 times more likely for endovascular coiling as compared to surgical clipping. [3]

Therefore it appears that although endovascular coiling is associated with a shorter recovery period as compared to surgical clipping, it is also associated with a significantly higher recurrence rate after treatment. It is unclear, however, whether the higher recurrence rate translates into a higher rebleeding rate, as the data thus far do not show a difference in the rate of recurrent hemorrhage in patients who had aneurysms clipped vs. coiled after rupture. [3] The long-term data for unruptured aneurysms are still being gathered.

Patients who undergo endovascular coiling need to have annual studies (such as MRI/MRA, CTA, or angiography) indefinitely to detect early recurrences. If a recurrence is identified, the aneurysm needs to be retreated with either surgery or further coiling. The risks associated with surgical clipping of previously-coiled aneurysms are very high. Ultimately, the decision to treat with surgical clipping versus endovascular coiling should be made by a cerebrovascular team with extensive experience in both modalities.

References

- ↑ Piotin, M (2007). "Intracranial aneurysms: treatment with bare platinum coils--aneurysm packing, complex coils, and angiographic recurrence". Radiology. 243 (2): 500–8. PMID 17293572. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Raymond, J (2003). "Long-term angiographic recurrences after selective endovascular treatment of aneurysms with detachable coils". Stroke. 34 (6): 1398–1403. PMID 12775880. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Campi, A (2007). "Retreatment of ruptured cerebral aneurysms in patients randomized by coiling or

clipping in the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT)". Stroke. 38 (5): 1538–1544. PMID 17395870. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); line feed character in|title=at position 80 (help)

See also

- Charcot-Bouchard aneurysm

- Intracranial berry aneurysm

- Stroke

- International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial

ca:Aneurisma cerebral de:Aneurysma#Hirn-Aneurysmata fi:Aivoaneurysma